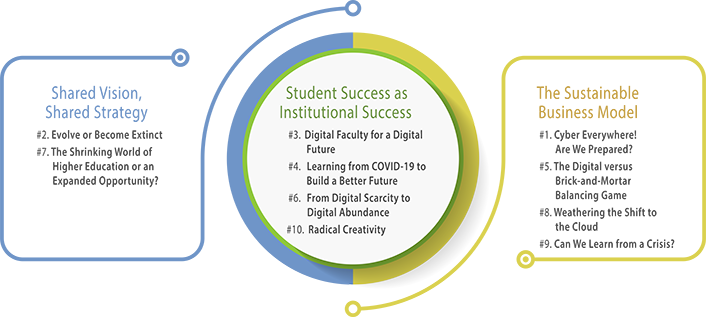

The EDUCAUSE 2022 Top 10 IT Issues take an optimistic view of how technology can help make the higher education we deserve—through a shared transformational vision and strategy for the institution, a recognition of the need to place students' success at the center, and a sustainable business model that has redefined "the campus."

"There will never be a return to what we knew as normal," a university president stated during one of this year's IT Issues leadership interviews.Footnote1 Here, as we begin another year of the COVID-19 pandemic, we all recognize that the higher education we knew will not return. The past two years have served as an inflection point at which the much-discussed and much-debated transformation of higher education has accelerated and proliferated.

Another leader, a chancellor, said: "The best opportunity is to redefine education right now. What does higher education look like in a post-COVID world?" The leaders we interviewed are not reflexively reacting to the changes in the world and simply watching their institutions adapt in response. Instead, they are redefining the value proposition of higher education by reshaping institutional business models and culture to anticipate and serve the current and emerging needs of learners, communities, and employers. Rather than working to restore the higher education we had, they are creating the higher education we deserve.

What is the higher education we deserve? One leader emphasized transformed teaching and learning: "I believe that we have the opportunity to reconceptualize how it is that we are no longer going to be in front of the classroom but, instead, we're going to be facilitators of knowledge."

Another leader described a more "customer"-focused institution: "Universities are going to have to become increasingly commercially-minded and agile and adjust much more to what students want and to what employers and governments are asking from higher education as well. The successful institutions will be the learning institutions that are able to respond more dynamically and be more agile in terms of their response, compared with those universities that are less reflective, less able to change."

Another president emphasized the need for colleges and universities to differentiate themselves. "One of the criticisms of higher education is that it is excessively homogenous. There is substantially less choice for people who want to engage with higher education than you might expect. We need to start carving out areas of very distinctive expertise and advantage and then plug those, in a modular way, into much bigger programs of work. I think the biggest transformation will be the move away from the cookie-cutter institutions that attempt to be all things to all people toward players who really carve out and dominate more spaces. And I think that's going to be a tricky journey."

Each leader defined the new higher education a bit differently, but all recognized that the higher education we deserve cannot be created without technology. In fact, for the first time ever, most leaders spoke of technology not as a separate set of issues but as a driver and enabler of, and occasional risk to, their strategic agenda.

The 2022 Top 10 IT Issues describe the way technology is helping to make the higher education we deserve.Footnote2 Making the higher education we deserve begins with developing a shared transformational vision and strategy that guides the digital transformation (Dx) work of the institution. The ultimate aim is an institution with a technology-enabled, sustainable business model that has redefined "the campus," operates efficiently, and anticipates and addresses major new risks. Successfully moving along the path from vision to sustainability involves recognizing that no institution can be successful and sustainable without placing students' success at the center, which includes understanding how and why to equitably incorporate technology into learning and the student experience.

2022 Top 10 IT Issues

- #1. Cyber Everywhere! Are We Prepared?: Developing processes and controls, institutional infrastructure, and institutional workforce skills to protect and secure data and supply-chain integrity

- #2. Evolve or Become Extinct: Accelerating digital transformation to improve operational efficiency, agility, and institutional workforce development

- #3. Digital Faculty for a Digital Future: Ensuring faculty have the digital fluency to provide creative, equitable, and innovative engagement for students

- #4. Learning from COVID-19 to Build a Better Future: Using digitization and digital transformation to produce technology systems that are more student-centric and equity-minded

- #5. The Digital versus Brick-and-Mortar Balancing Game: Creating a blended campus to provide digital and physical work and learning spaces

- #6. From Digital Scarcity to Digital Abundance: Achieving full, equitable digital access for students by investing in connectivity, tools, and skills

- #7. The Shrinking World of Higher Education or an Expanded Opportunity? Developing a technology-enhanced post-pandemic institutional vision and value proposition

- #8. Weathering the Shift to the Cloud: Creating a cloud and SaaS strategy that reduces costs and maintains control

- #9. Can We Learn from a Crisis? Creating an actionable disaster-preparation plan to capitalize on pandemic-related cultural change and investments

- #10. Radical Creativity: Helping students prepare for the future by giving them tools and learning spaces that foster creative practices and collaborations

Shared Vision, Shared Strategy

To help create the higher education we deserve, institutional departments and divisions must have a shared vision and be willing and able to plan and act collaboratively. Otherwise, they will always be operating at cross-purposes in which the success of individual areas takes precedence over organization-wide success. Digital transformation is helping institutions retire old ways of thinking and working in order to harness technology to transform institutional outcomes. Institutions need to build the foundations of digital transformation through shifts in their culture, workforce, and technology.Footnote3 Institutions will focus on three shifts in 2022: operational efficiency, agility, and workforce development (Issue #2).

But the foundation work alone is insufficient. Shifts in culture, workforce, and technology need to be focused on a particular outcome. Institutions will be developing a vision and corresponding value proposition for their institution that takes them beyond the pandemic, and they will be harnessing technology to attain that vision (Issue #7).

#2. Evolve or Become Extinct

Accelerating digital transformation to improve operational efficiency, agility, and institutional workforce development

#7. The Shrinking World of Higher Education or an Expanded Opportunity?

Developing a technology-enhanced post-pandemic institutional vision and value proposition

Student Success as Institutional Success

The higher education we deserve is one in which institutions embrace students as their primary customers. No longer can institutions dictate the terms and conditions of students' educational experiences and outcomes. Institutions will be optimizing their offerings to meet students' needs. That includes treating access as an institutional, rather than learner, responsibility (Issue #6), developing services that are designed with the student in mind (Issue #4), designing equitable teaching and learning that works for all individuals, not just those in the "mainstream" (Issues #3, #4, and #6), and focusing on creativity and innovation in teaching as well as learning (Issues #3 and #10).

#3. Digital Faculty for a Digital Future

Ensuring faculty have the digital fluency to provide creative, equitable, and innovative engagement for students

#4. Learning from COVID-19 to Build a Better Future

Using digitization and digital transformation to produce technology systems that are more student-centric and equity-minded

#6. From Digital Scarcity to Digital Abundance

Achieving full, equitable digital access for students by investing in connectivity, tools, and skills

#10. Radical Creativity

Helping students prepare for the future by giving them tools and learning spaces that foster creative practices and collaborations

The Sustainable Business Model

The higher education we deserve needs to be able to operate efficiently and manage risks effectively. It needs to be sustainable. Done well, technology can help organizations control and reduce costs, as well as scale beyond their size (Issues #5 and #8).

In the 21st century, we are surrounded by all kinds of risks, and we need to be able to anticipate, prepare for, and manage them. Technology can help mitigate risks to place-based learning and work, and all the pivots that occurred during the pandemic have reduced institutional dependence on the physical campus (Issue #9). Yet technology in the form of data security is also among the top risks in higher education (Issue #1). As long as that remains true, cybersecurity management will remain high on the EDUCAUSE Top 10 IT Issues list.

#1. Cyber Everywhere! Are We Prepared?

Developing processes and controls, institutional infrastructure, and institutional workforce skills to protect and secure data and supply-chain integrity

#5. The Digital versus Brick-and-Mortar Balancing Game

Creating a blended campus to provide digital and physical work and learning spaces

#8. Weathering the Shift to the Cloud

Creating a cloud and SaaS strategy that reduces costs and maintains control

#9. Can We Learn from a Crisis?

Creating an actionable disaster-preparation plan to capitalize on pandemic-related cultural change and investments

What is the higher education we deserve? It is the higher education that our learners deserve. How do we get there? By beginning with a shared vision and strategy to achieve a sustainable business model that places students' success at the center of it all.

Additional Resources on the EDUCAUSE 2022 Top 10 IT Issues Website

-

A video summary of the 2022 Top 10 IT Issues

-

An infographic about the 2022 Top 10 IT Issues

-

International perspectives on the 2022 Top 10 IT Issues

-

Corporate perspectives on the 2022 Top 10 IT Issues

-

The 2022 Top 10 IT Issues presentation at the EDUCAUSE 2021 Annual Conference

-

2022 Higher Education Trend Watch

2021–2022 EDUCAUSE IT Issues Panel Members

|

Name |

Title |

Organization |

|---|---|---|

| Bella Abrams | CIO | University of Sheffield United Kingdom |

| Jeremy Anderson | Associate Vice Chancellor, Strategic Analytics | Dallas College |

| Wendy Athens | Senior Director | Utah Valley University |

| Jon Bartelson | Assistant Vice President for Information Services & Chief Information Officer | Rhode Island College |

| Steve Burrell | VPIT & CIO | Northern Arizona University |

| LeRoy Butler | Chief Information Officer | Lewis University |

| Tiffni Deeb | Chief Information Officer | Minneapolis Community and Technical College |

| Melissa Diers | Director of Academic Technologies | University of Nebraska Medical Center |

| Scott Erardi | Senior Project Manager | Quinnipiac University |

| Jared Evans | Information Security Officer | Gallaudet University |

| Kati Hågros | CDO | Åalto University Helsinki, Finland |

| Paul Harness | Director of Information Systems Services | Lancaster University United Kingdom |

| Suzanne Healy | Director, Online & Hybrid Learning | Case Western Reserve University |

| Joanne Kossuth | Chief Innovation Officer | Mitchell College |

| Orlando Leon | former Vice President for Information Technology and Chief Information Officer | California State University, Fresno |

| Dolores Marek | Director, Academic Technology | Columbia College Chicago |

| Trina Marmarelli | Director Instructional Technology Services |

Reed College |

| Dan Mincheff | Chief Information Officer | Northeast Wisconsin Technical College |

| Joseph Moreau | Vice Chancellor of Technology & CTO | Foothill-DeAnza Community College District |

| John Murphy | Director of IT | Mohamed bin Zayed University of Artificial Intelligence |

| Nela Petkovic | Chief Information Officer | Wilfrid Laurier University Waterloo, Canada |

| Michelle Rakoczy | Associate Director Infrastructure & Operations | North Dakota University System |

| Nina Reignier-Tayar | Directrice d'Appui Numérique à l'Administration | Université Grenoble Alpes Grenoble, France |

| Shana Sumpter | former Director of Information Security | University of Richmond |

| Thomas Trappler | Associate Director IT Strategic Sourcing |

University of California System |

| Phil Ventimiglia | Chief Innovation Officer | Georgia State University |

| Raimund Vogl | CIO and director of WWU IT | Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität (WWU) Münster, Germany |

| Gina White | Director Technology Services | Southern Cross University |

| President | CAUDIT (Council of Australasian Directors of Information Technology) |

Issue #1: Cyber Everywhere! Are We Prepared?

Developing processes and controls, institutional infrastructure, and institutional workforce skills to protect and secure data and supply-chain integrity

Michelle Rakoczy, Nina Reignier-Tayar, Thomas Trappler, and Gina White

"What risk level are we willing to assume as institutions to best meet our mission? We're struggling with trying to create the right kind of technical environments to be able to share data and to access it. I'm going to want more information, I'm going to have more people who have it, and the security folks are going to be more concerned because people are getting more clever about getting access to the data, and the risk of us inadvertently sharing data in ways that we shouldn't is very real and significant."

—Ron Anderson, President, Senior Vice Chancellor, Minnesota State Colleges and Universities

Cybersecurity threats and incidents are increasing globally and becoming more difficult for users to recognize and for cybersecurity programs to detect. One incident can cause loss of reputation and loss of educational opportunities for students, as well as financial and reputational issues for both the campus and the individuals impacted.

As technology provides more of the foundation on which higher education institutions conduct their core operations, building processes, controls and training that ensure continuity of access and ongoing integrity of those underlying IT products becomes business-critical. Without this, the ability of an institution to function could come to a grinding halt.

To succeed, institutions should not treat cybersecurity as a technical subject. It should be an institutional priority. Cybersecurity is a team sport inside an institution, as well as across the higher education sector in countries, regions, and the world. All of us in our sector need to work together to safeguard our universities.

Challenges in 2022

The pandemic and changing technology architectures are complicating the ability of institutions to provision and secure the supply chain on which institutional infrastructure is so dependent. Additionally, global supply-chain disruptions can have far-reaching effects. For example, computer shipping shortages impact the availability of computing devices, consumer goods, automobiles, cloud computing, and more. Both cloud suppliers and institutions are struggling to obtain newly limited resources.

According to many studies, teleworking and online/hybrid courses will continue to exist after the Covid-19 crisis.Footnote4 This means that the institutionally provisioned or personally owned devices that staff and students use for working and learning may also be used by family members or for personal purposes. Both cases are challenges that can lead to a security breach.

What were once clear distinctions among hardware, software, cloud, and services and between primary and secondary suppliers continue to blur and overlap to the point where they're no longer distinguishable as separate categories. That raises questions and challenges about identifying the perimeter—or, where institutionally owned and managed technology infrastructure ends. Additionally, the integration between technology run in-house and that run by an external supplier continues to blur boundaries between consumers' responsibilities and suppliers' responsibilities. That, in turn, creates the challenge of clarifying which technology and data components can and should be secured by institutions versus by suppliers versus by end users and, thus, where security risk factors and responsibilities reside. Sometimes suppliers' security and privacy controls may not be as tight as institutions require or realize.

If institutional leaders have not already addressed these risks during the pandemic, they will have to extend cybersecurity policies, processes, training, and other protections to these use cases. Tools like the EDUCAUSE Higher Education Community Vendor Assessment Toolkit, developed for use across the entire higher education sector, can help clarify institutional security requirements and suppliers' ability to meet them.

Impacts on Culture

Both mindsets and behaviors need to change. All faculty, staff, and students at an institution need to understand their cybersecurity responsibilities and adapt to (often legally mandated) institutional controls and processes that may very well introduce new restrictions and access.

Recent events—including the Colonial Pipeline and higher education ransomware attacks and the Accellion and SolarWinds security breaches—indicate the urgent need for additional due diligence in addressing IT supply-chain integrity. In this new environment, a breach of availability, integrity, or confidentiality at any point within this complex ecosystem may have significant unexpected repercussions on other points.Footnote5 Institutional leadership will need to acknowledge and support the need for strong collaborative partnerships among procurement, IT, cybersecurity, and legal units to effectively mitigate these IT supply-chain risks.

Culture clashes between data preservationists and leaders managing institutional risk and legal exposure may intensify as higher education institutions introduce more conservative records-retention policies and processes. Institutions that can frame data security and privacy protection as partnerships among various stakeholders may see fewer of these and other culture clashes.

Helping the Institutional Workforce Succeed

Finding and funding cybersecurity staff has gotten harder, as the pre-pandemic shortage of cybersecurity professionals continues and as pandemic-related budget cuts challenge institutions to afford qualified staff. The burden falls on existing staff, who are burned out and overworked. Some cybersecurity tasks can be outsourced, however, to extend staff and/or acquire specialized skills. For example, institutions can hire consultants to perform an information systems security audit, identify gaps, and work with existing staff to develop a plan to prioritize and address the gaps.

Even better, if the entire institutional workforce possesses an up-to-date understanding of how incidents happen and what can be done to prevent them, all staff can collectively reduce the operational burden on cybersecurity staff, as well as better safeguard data and privacy.Footnote6

Needed Technologies and IT Capabilities

Technologies for patch management, endpoint detection and response (EDR),Footnote7 data loss prevention (DLP), and security information and event management (SIEM) are all useful. Setting up security operations centers is even more important than the tools, though, as is having qualified staff with access to the proper tools and monitoring.

Once institutions have invested in cloud solutions, what institutional leaders think of as "their" IT infrastructure now extends globally and introduces new dependencies and risks. An attack on a supplier can endanger and disable institutional services and data. Another capability that institutions need is business continuity to help anticipate and prepare for such issues.

Transforming Higher Education

Cybersecurity is expensive and challenging and becoming only more of both. Institutions that collaborate to manage cybersecurity can share costs and expertise, both reducing the burden on individual institutions and increasing the level and effectiveness of cybersecurity at institutions of all sizes. We are already seeing promising steps in this direction. The University System of North Dakota is partnering across its institutions and with the state of North Dakota to work collectively with supplier partners and to introduce programs that benefit all. Australasia is partnering regionally, with higher education institutions and the Australian and New Zealand governments, to deliver cybersecurity awareness training and to share the costs of a security operations center (SOC). Institutions in the University of California system are working together to identify and establish agreements with best-in-class IT security tools suppliers.

A second desired transformation would be for institutions to better recognize and prioritize students as primary stakeholders in cybersecurity. When students don't understand how their institution uses personal data, their trust in that use and their confidence in how their institution protects personal data erodes.Footnote8 They hold institutions accountable for the security of their data. Institutional leaders and cybersecurity professionals need to focus on individuals, in addition to the institution, and never lose sight of the potential financial, reputational, and mental health consequences that data breaches can have on any student whose data or privacy is breached.

Issue #2: Evolve or Become Extinct

Accelerating digital transformation to improve operational efficiency, agility, and institutional workforce development

Bella Abrams, Jeremy Anderson, Tiffni Deeb, and Thomas Trappler

"I see a very substantial role for technological transformation. We have to develop processes that we can automate or at least filter using AI, robotics, and things of that nature. There are good examples of processes that are super mission critical, like university admissions, which I think will radically transform in the next five years through use of technology. And if we fail, what we're going to fall on is that our speed to market and our cost of doing business are basically going to be threats to us."

—Tyrone Carlin, Vice Chancellor and President, Southern Cross University, Australia

Technological transformation happens, whether we like it or not, and at an increasingly rapid pace. Effectively managing the complex underlying collection of IT goods and services, and associated integrations, can transform institutional operations, enabling greater efficiency and innovation. Accomplishing this requires a high level of coordination and planning by institutional leadership, including the need to integrate technology and its procurement into the associated strategic planning processes. An impediment to digital transformation in higher education is that processes, services, and use of data often have not been designed but have evolved, without structured thinking about efficiency, effectiveness, and outcomes. Digital transformation entails optimizing and transforming institutional operations, strategic directions, and value proposition through deep and coordinated shifts in culture, workforce, and technology. Dx initiatives begin with a strategic outcome and entail holistic, coordinated efforts. Rather than improving operational efficiency, introducing data governance and integration, or implementing technical solutions as separate, unrelated projects, Dx initiatives may address them collectively to achieve a particular outcome. Many of today's Dx efforts focus on student outcomes and experiences.

While Dx initiatives help attain strategic outcomes, they also increase institutional capabilities, resulting in greater agility, operational efficiency, and staff knowledge and skills. The institution is thus better positioned for even deeper transformations.

Challenges in 2022

The increasingly diverse range of different technologies and IT services, and the need to integrate, will continue to present challenges. Additionally challenging is accomplishing the above while also effectively implementing new hybrid learning and work environments stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic. Institutions may lack the resources to fund transformative efforts. The coming demographic cliff—a steep drop-off in potential first-time full-time freshmen projected to arrive in 2025 due to the decline in birth rate in the 2008 recession—may further erode enrollment income at US institutions. As the pandemic drags on, its impact on staff members' health compounds the problem. Staff – including leaders – may run out of the ability to reimagine, reinvent, and retool.

While the pandemic has accelerated digital transformation in many ways, some approaches and responses have been necessarily rushed and tactical, resulting in fixes that may not scale or have applicability beyond the pandemic. Institutional leaders will need to create a comprehensive strategic plan with elements that can be prioritized and addressed incrementally to balance limited energy and resources with lasting, meaningful outcomes.

Impacts on Culture

Technology changes rapidly, often offering opportunities to improve efficiency and effectiveness. Institutional leaders will have to dismantle siloed work in order to achieve institutional excellence. Siloes reflect organizational structure rather than strategic outcomes such as student success or financial health. Processes, guidelines, tools and technologies, and data are often siloed. Shared, strategic outcomes can inspire stakeholders to understand the greater good and the need for establishing common solutions that are equitable, inclusive, and more affordable.

Such adjustments involve change. Change decisions can't be made behind closed doors. They will require dialogue across staff groups and student groups to help all stakeholders understand and agree on goals and feel that they have a hand in choices and timing. Institutional leaders will need to become increasingly comfortable with, and effective at, change agility while also maintaining focus on strategic goals.

Helping the Institutional Workforce Succeed

Digital transformation requires a new set of skills and competencies across the institutional community. New, needed technology-related skills include strategic sourcing, contract management, supplier relationship management, user experience and design thinking, product management, and enterprise architecture. The entire workforce will need deeper data skills and greater ability to collaborate and partner. Human resources staff and workforce managers will need to become more effective at workforce planning and talent management. If the institution continues to function as a hybrid office-based and work-from-home organization, all staff will also need to gain skills in managing, communicating, collaborating, and working productively in this hybrid work environment.

Needed Technologies and IT Capabilities

While digital transformation depends on technologies and IT capabilities, success arguably depends more on how technologies are chosen and adopted than on which technologies are chosen and adopted. Technology choices should proceed from, not precede, shared agreement on outcomes and functionality. Academic and administrative leaders understand what they want to achieve, but the most effective technology decisions take an institution-wide, rather than department-specific, perspective. Leaders must invite varied staff to the table: technologists to advise on accessibility, interoperability, security, and sustainability; equity experts to assess fairness and impartiality; and IT strategic sourcing experts to effectively manage competitive selection processes and negotiate the most favorable terms.

Transforming Higher Education

Digital transformation may enable institutions to break the classic "iron triangle" rule that says it is possible to maximize only two of the three desirable outcomes: cost, speed, and quality. Dx efforts often involve systems and data integrations, which can lead to both lower costs and better services and experiences. They will provide a holistic view of students, alumni, employees, resources, and more in ways that can result in beneficial outcomes. New architectures increase access to data and resources, which can offer better insights about institutional products and services and enable faster, more accurate decisions.

These changes lay the groundwork to provide students with a more affordable education as well as the skills and credentialing they need to have the work and employment that they desire and to do so at a time that fits their lives.

Issue #3: Digital Faculty for a Digital Future

Ensuring faculty have the digital fluency to provide creative, equitable, and innovative engagement for students

Orlando Leon, Dolores Marek, John Murphy, and Shana Sumpter

"COVID has kind of pushed us in this direction of online teaching. Even faculty who are resistant were forced into an environment where they had to use the technology. And I've heard from some faculty that they had no idea how innovative they could be with some of this technology in their classrooms."

—Nathan Brostrom, Executive Vice President and Chief Financial Officer, University of California Office of the President

Students expect their higher education institutions to provide a certain level of digital sophistication in delivering learning and services. For many students, the digital medium is their default way to learn, interact, and get things done. Although the pandemic has required even the most technology-averse faculty to adopt digital instruction, they will need help and encouragement to continue to develop their skills in using innovative instructional technologies.

Instructional and pedagogical technologists understand that technology choices need to be made part of the curriculum-development process, not just layered on at the end. Now is an ideal time for faculty to step back and reevaluate their courses and programs through the lenses of delivery mode and technology integration. That takes time. Teaching and learning support center staff can shoulder some of the burden for faculty.

Institutional leaders need to invest more in training, instructional design support, and spaces where faculty can experiment with innovative teaching technologies.

Challenges in 2022

Gaining buy-in from some faculty is one challenge. But the greater problem today is that many faculty are overwhelmed by the intense ongoing demands of the pandemic. Not all faculty who started remote instruction during the pandemic enjoyed it, and some want to revert entirely and permanently to face-to-face teaching.

Faculty aren't the only ones who are burned out. Instructional and pedagogical designers and technologists have been among the technology staff most overworked during the pandemic,Footnote9 and now they are being asked to support and help integrate remote and in-person instructional methods. Those staff are a flight risk too, as competition for a very limited pool of such professionals intensifies.

The uncertainty of the pandemic, plus institutional and governmental approaches to managing it, will also generate ongoing disruption and churn. That's likely to exacerbate burn-out among faculty, staff, and students.

Impacts on Culture

Moving toward a digital future with digital faculty requires infusing digital strategy into the pillars of the institutional strategy and missions. Higher education institutions will need to add digital dimensions to governance structures and processes, which of course should involve faculty and incorporate students' perspectives. Including digitally-savvy faculty on academic leadership teams can help—and so can finding ways to integrate core technology requirements into the tenure and promotion process.

Leaders need to encourage collaboration and partnerships across academic departments and among pedagogical experts, technologists, and faculty. Using collaborative technologies like Slack or Microsoft Teams can foster dialogue and community around how faculty are using technology in their teaching, how they are teaching, and how they are changing the curriculum. Partnerships with businesses can also provide exciting and well-funded opportunities to experiment with teaching and technology.

Helping the Institutional Workforce Succeed

Faculty need training, of course. Those staff who are leading digital faculty initiatives might design training around a digital competency framework. Training will need to be ongoing to keep up with the speed with which digital tools change.

The mindsets of both faculty and staff will need to shift. To help encourage those shifts, organizational leaders will have to introduce supports such as change management and collaboration incentives for faculty, pedagogical and instructional technologists, and other technology staff.

Many people are feeling depleted now, so as leaders introduce and advocate for change, they should try to find ways of helping faculty and staff attain and maintain emotional equilibrium and well-being.

Leaders will also have to introduce new expectations for digital fluency among faculty in the context of continued adaptations to the changing pandemic situation. This may be an ideal time to change expectations, because many faculty are trying to recalibrate their teaching methods and materials to the pandemic situation and to what they've learned about digital instruction.

Needed Technologies and IT Capabilities

Technologies and capabilities are needed at all layers. A digital teaching and learning future demands robust, equitably delivered infrastructure that has the capacity to move and store digitized datasets, images, music, and videos and that is designed to accommodate remote locations and devices. Policies can help democratize and standardize resources and resource levels across have- and have-not departments to provide students with consistent experiences and to provide faculty with equitable resources and support. Standardizing learning space management can help simplify faculty's use of learning spaces.

Learning analytics can help faculty adapt their teaching to identify and support students quickly and efficiently. Assessment technologies, although often controversial, are maturing, and with the help of learning and assessment advocates, these technologies can become more valid and better safeguard privacy. New consumer-focused artificial intelligence products may appear in the next year or two also. All these technologies will demand careful processes and policies to ensure that they are being used ethically and equitably. Perhaps the most exciting and fun possibilities exist with gaming and extended reality applications.

In all these cases, new technologies will introduce new costs, support requirements, and training needs. Academic leaders will be better off introducing only new technologies that they can fully support. Innovation and exploration can be encouraged at the grassroots level, and then when small pilots are successful, those technologies can be moved to a supported service catalog.

Transforming Higher Education

For institutions that are already adopting digital learning, the transformation is underway. More interesting, perhaps, is to speculate on how higher education institutions that are committed to a campus-based experience will define and develop "digital" faculty. Students will have the greatest influence over the incorporation of digital experiences and learning opportunities into courses and curricula. Will anytime, anywhere learning become an expectation of all students, even those who attend campus-based institutions? If so, when will this happen? Will new generations of faculty be so digitally adept that this issue will lose its relevance?

Most important is to have a digital faculty strategy that is tied to important outcomes. Student success—whether defined as completion, retention, affordability, employability, learning, or all five—is one outcome on which to align a digital faculty strategy. Equity and accessibility must also be incorporated into both outcomes and digital learning strategy. The process of increasing digital fluency will help institutional leaders focus on outcomes, so faculty digital fluency should be addressed in the context of good pedagogical design and measurable learning outcomes.

Issue #4: Learning from COVID-19 to Build a Better Future

Using digitization and digital transformation to produce technology systems that are more student-centric and equity-minded

Wendy Athens, Jared Evans, Dan Mincheff, and Michelle Rakoczy

"We talk about being student ready, so how do we help students become technology ready? Because that's going to be a part of how they're going to receive their education. I think it will put a stronger emphasis on our digital presence. Going back to the ease of use of our website, our student portals, our LMS, all of those things that we're going to lean more heavily on in the future. That will become as important as the brick and mortar. So this definitely is transforming higher education."

— Dan Mincheff, Chief Information Officer, Northeast Wisconsin Technical College

The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted almost all facets of higher education. It amplified strengths, demonstrating that effective processes and people can work in a wide variety of situations and scenarios, and it exposed gaps that have long needed to be filled. The pandemic required institutions to focus on core needs and services, strengthening the ones that worked and reinventing the ones that did not. It jump-started digital transformation at many institutions.

During the pandemic institutions returned to first principles and to their primary customers: students. Institutional leaders and faculty learned just how many students lack broadband and devices other than a smartphone. The quick fixes during the pandemic need to give way to comprehensive efforts to ensure that students have sufficient and equitable access to educational resources and opportunities. Technologies like Zoom gave faculty a platform for digital instruction, but faculty need more help truly integrating technology into distance, hybrid, and classroom education. That help needs to take many forms, including pedagogical design, learning space design, and courseware and other instructional technologies.

Students also need more effective technology-mediated advising and support services. As institutional leaders begin to better understand the many extra-academic factors that contribute to students' success, they are introducing and expanding student services ranging from financial aid to mental health services to transportation, child care, and food services. Technology can offer students conveniences such as online scheduling for services, online progress reports and updates, and virtual appointments/meetings.

We have all learned a lot. Institutional leaders need to use their new learnings, processes, and capabilities to permanently change the way they are going to conduct campus business moving forward.

Challenges in 2022

We have entered a new, more complicated phase of the pandemic. Higher education institutions and individuals are trying to achieve something resembling pre-pandemic life while remaining in the midst of a pandemic. This swing back to previous service levels and the ongoing lack of consensus among state and federal leaders effectively prohibit institutional leaders from mandating anything. As a result, two sets of expectations have been established: (1) those established during the first phase of the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., distance learning, remote work, and loosened controls), and (2) the more traditional, pre-pandemic campus-based learning and work. Students, faculty, and staff want to be able to choose among all these options and have a seamless customer experience.

Trying to expand digital services is particularly difficult at this time, however. Reliable planning and provisioning is a challenge as supply-chain irregularities continue, While digital literacy has improved during the pandemic, staff and students need to further develop digital skills to work and learn productively. Yet faculty, staff, and students are tired, stressed, and overwhelmed.

Impacts on Culture

In the first phases of the pandemic, institutions made great progress toward anytime, anywhere working and learning. Now everybody—including students who don't want to leave their homes or dorm rooms to go to class and staff members who want to work at home or want flexible schedules—expects greater adaptability and flexibility. If digital transformation is to be successful, institutional leaders need to step back and reflect on what's been learned and gained, align on desired outcomes, and decide how to move forward with intentionality.

Helping the Institutional Workforce Succeed

Instructional support and IT staff must provide more training for faculty and staff, to keep them up-to-date and to ensure that they have the skills needed to teach and work securely and effectively beyond the traditional campus. Strong relationships and ongoing communication among IT leaders, staff, faculty, and administrative leaders are essential for technologists to design and deliver great services and for institutions to use technology to its maximal strategic value.

With so many more faculty teaching online, teaching and learning managers and IT support centers may struggle to maintain sufficient staffing levels. The Higher Education Emergency Relief Fund (HEERF) under the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act provides only point-in-time funding. New strategies to sustain service levels will be needed, such as appointing digital instruction leaders in each academic department to liaise with the support unit and serve as a communication mechanism to get information out and to support conversations about using technology in the classroom.

Needed Technologies and IT Capabilities

Institutions will need technologies that enable access and services, from wherever employees or students are, to support hybrid working and learning. Services need to work just as well for students with limited access to technology or special accessibility requirements. Many institutions are also still searching for a flexible but feasible solution for hybrid learning.

Technology can introduce play into learning. Technologies that support more immersive, interactive, and fun learning—such as extended reality solutions—may offer an online, asynchronous learning experience to augment a completely in-person class. Technologies that can help students build community and connectedness are also important in these often isolating times.

Of course, the infrastructure that supports flexible, fun learning and socializing needs to be just as well-managed and secure as the rest of the institutional digital infrastructure. Disaster recovery and business continuity are part of good management, as is effective supplier relationship management.

Transforming Higher Education

During the pandemic, higher education became an enormous incubator for digital transformation. New possibilities—and expectations—have emerged. As a result, academic leaders and faculty may introduce novel ways to deliver the curriculum and showcase new and exciting ways for students to learn. Flexibility is going to be key moving forward. Faculty have shown students they can switch modes if and as needed. How do they now simplify the process to leverage flexibility as an advantage?

These transformations will put a stronger emphasis on the digital presence of higher education institutions. The digital campus will become as important as the brick-and-mortar campus. The two models will coexist at many institutions, forcing leaders to consider what can be done only on campus and what can be done virtually. The shift of funding to support hybrid campus operations and planning will be as disruptive as the shift, spurred by cloud computing, from capital to operational funding. Many US state funding models are based on physical space and uses of it. That's not going to work under the new paradigm. Finding the right balance between physical and virtual presence for all members of the campus community will be imperative for a successful future.

Issue #5: The Digital versus Brick-and-Mortar Balancing Game

Creating a blended campus to provide digital and physical work and learning spaces

Jon Bartelson, LeRoy Butler, Scott Erardi, and Paul Harness

"If we're flexing large-scale lectures and exploring ways to 'flip the classroom' by creating online opportunities that extend and enrich our face-to-face teaching, what does that mean for all the lecture theaters that we have, and what other forms of flexible teaching and student engagement space will we need? And equally, if we're starting to think about change to more blended working practices, what does that mean about the office accommodations and meeting spaces we have on campus? And if we start working differently and release some of that space, what does that afford us in terms of opportunities for repurposing space and thereby reducing the carbon intensity of capital programs on campus?"

—Simon Guy, Professor and Pro-Vice-Chancellor Global (International, Digital, Sustainability, Development), Lancaster University, United Kingdom

During the COVID-19 pandemic, higher education leaders, faculty, and staff have learned many things about how to provide a quality educational experience for students. As they have begun to transition back to campus-based activities, many leaders are viewing this as an opportunity to reimagine what the "campus" is and how it works.

For many institutions, such reinvention is imperative because enrollments have declined and likely will continue to decline due to both the pandemic and broader demographic changes. Commuting to or living on campus does not often fit the lives of students when they're balancing family, community, and career commitments with the desire to further their education. Administratively, many institutional teams have gained productivity by working remotely or in hybrid ways.

Options for reimagining the campus include (1) redesigning campus physical spaces to support hybrid learning and work, (2) addressing space crunches by encouraging administrative groups to work remotely and then converting administrative spaces to academic spaces that support learning, research, and scholarship that is better conducted on campus, and/or (3) lowering costs by reducing the physical campus space.

Challenges in 2022

Transforming a campus wisely and well is not a rapid process. As the pandemic drags on, leaders are struggling simply to plan for the next week. But leaders need to begin anticipating the post-pandemic future of their institutions, even as the pandemic continues. Many of them lack reliable information about how many of their current and prospective students will want campus-only, hybrid, or fully online educational experiences. Powerful anecdotes can dominate data, which may lead institutions to overcorrect in one direction or the other.

Impacts on Culture

As a result of the pandemic, students want and expect more opportunities outside of the normal, traditional hours that institutions typically offer. They want weekend, evening, and holiday hours for everything from classes to student services to the library. Many institutional leaders are considering whether to make big bets on technology to change the game at their campuses. Those big bets will have major impacts on institutional culture and the very nature of how constituents get work done. Having fewer students on campus may reduce students' interest in and attendance at campus events and activities. Many faculty want the flexibility of being able to work in a more hybrid way, but they want to do so on their terms, such as retaining their campus offices. Staff may be more willing to adapt to new working spaces and arrangements, but they are anxious about the details and personal impact. For example, many staff expect institutions to fully equip their home working spaces while also keeping their institutional working spaces. Few institutions will be able to afford that level of "both and." So while the possibility of flexibility and saved time from commuting is appealing, leaders will have to listen, prepare, and communicate carefully.

Helping the Institutional Workforce Succeed

Becoming a fully blended campus will change the way all institutional constituents work and form community. People will need help and training to adapt to and gain mastery with new tools and ways of working and collaborating. Physical and digital space and service planners will need to design physical and virtual spaces and ways of working and teaching in partnership with, and getting significant ongoing input from, students, faculty, and staff.

Human resource leaders should consider new programs to incentivize digitally-savvy job applicants to join the institutional workforce, to help design and also model ways to digitally transform work, instruction, and research. Fully remote work arrangements could be used to further attract these applicants to roles that fit the needs of both the future employee and the institution.

Needed Technologies and IT Capabilities

The biggest challenge may be finding ways of successfully working and learning in a hybrid mode. Meetings, teaching, and other synchronous group activities work best when everyone is online or when everyone is in the same room. Technologists are investing in various technologies that support "dual mode" instruction or meetings; these technologies include additional cameras, screens, audio, and collaboration technologies. Not every effort will work, so technologists often frame the technologies as experiments or pilots and encourage faculty and staff to test various options. Yet the solution is not only a technical one; equally important is re-engineering academic and work processes to enable people to conduct their work in a seamless way regardless of the modality.

Technologies supporting anytime, anywhere access are also in demand. Since the pandemic began, faculty have become more eager to use cloud-based services for research and teaching. Many institutions have greatly expanded wireless capabilities on campus to support the increased number of institutional services and applications that have been digitized and made mobile-friendly.

Transforming Higher Education

The physical campus is unlikely to disappear at most institutions. Rather, the digital campus can offer flexibility in, and alternatives to, how students learn, how faculty teach and engage in research and scholarship, how staff work, and how all constituents form enduring and engaging relationships and communities. As students, faculty, and staff adjust to hybrid learning and work, they will make choices that change the way physical space is used, creating, for example, less need for dormitories or increased demand for fully online classes (and thus reduced demand for physical classrooms). The transformation of higher education may be more evolution than sudden disruption—an evolution shaped by all stakeholders.

Reimagined and transformed ways of working and learning will prepare institutions to serve current and future generations of students, including growing numbers of lifelong learners looking to upskill, reskill, or simply satisfy their curiosity.

Issue #6: From Digital Scarcity to Digital Abundance

Achieving full, equitable digital access for students by investing in connectivity, tools, and skills

Steve Burrell and Trina Marmarelli

"Technology is about so much more than just the devices. It's also about the environment in which our students can or cannot access technology."

—Judy Miner, Chancellor, Foothill-DeAnza Community College District

The pandemic made it painfully clear that in the United States, digital voids in both rural and urban areas most adversely affect Black, Latino/Latina, and indigenous people, as well as people with disabilities and people experiencing poverty. The digital divide is about more than access to reliable high-speed internet. Students also need equitable access to devices, software, and the skills required to be successful students and, later, to thrive in the workplace.

The same thinking that got us here won't get us there. Higher education leaders must act on a holistic strategy for equitable digital access and must invest in sustainable ways to provide access in order to avoid inadvertently widening the digital divide. Institutional leaders have a pivotal role to play in reimagining what equity means. Leaders will need to make difficult choices; in some cases, return-on-investment may not be the measure of success.

Challenges in 2022

The flood of funding around infrastructure and the COVID-19 pandemic has created tremendous swirl and confusion about broadband initiatives. Ultimately, this situation will sort itself out, but until then, knowing who is investing what and where can be difficult to determine. In higher education, we need to be careful that we're investing money in areas and people where there is real need even if not necessarily a sustaining market with predictable return on investment.

Another difficulty is the ongoing uncertainty about the course of the pandemic and its impact on institutional operations and on how to ensure that students have the access they need when they need it. As the pandemic has settled in and claimed another academic year, institutional leaders find themselves having to prepare for a much wider range of circumstances than in the initial phases of the pandemic.

Broadening and sustaining access requires software as well as hardware. Software is increasingly licensed annually using operational funding. Additional funding will be needed to bolster operational budgets during a period of increasingly limited resources. Hard decisions and careful fiscal planning are needed to create sustainable digital abundance. Worse than not addressing this issue may be the need to abandon investments later, leaving stakeholders disenfranchised.

Impacts on Culture

Progress on achieving full digital access for students will be held back by existing biases and attitudes about organizational and personal productivity. The idea of working anytime, anywhere has widespread appeal and value, but not all institutional leaders are prepared to adopt it. Similarly, many faculty and academic leaders are entrenched around the idea that certain modalities of teaching and learning are intrinsically better or more effective than others. That must change to serve the "everywhere" learner (and the "anywhere" faculty).

The academic culture of high levels of autonomy for faculty over how they teach their courses, present their information, and engage with their students is in many ways a wonderful thing. But it can also impede achieving fully equitable digital access for students. When faculty are choosing their own technology platforms without considering the broader institutional context, students often have to navigate a convoluted landscape of technology platforms and tools. A shift in the institutional culture toward presenting students with a more streamlined technology toolkit, without compromising pedagogy, could go a long way toward achieving more seamless access for students.

Needed Technologies and IT Capabilities

Additional investments are needed in campus network infrastructure and the highly skilled technical staff to support it. Beyond bandwidth, technologies such as virtual desktops and access to education applications and information independent of place are now a necessity.

Institutions will need IT staff who are able to engage with students to provide them with the technology training and skills that they'll need to be successful.

Technologies such as adaptive learning and augmented reality can remove barriers to learning and open new opportunities for learning, discovery, and experiences. Investments in these technological tools must be matched with investments in people and with rethought processes. Faculty will need to learn about and adapt or adopt new heutagogical methods to make the best use of these technologies. They must be well supported by IT staff who understand not just the technology but also the concepts behind its application to teaching and learning. Collaboration between faculty and staff is also necessary to ensure that digital accessibility is taken into consideration when evaluating and selecting technological tools, so that removing barriers for some students does not inadvertently create new barriers for others.

Helping the Institutional Workforce Succeed

Implicitly or explicitly, focusing on digital abundance for students puts students, rather than the institution or faculty, at the center of the institution. For that to happen, leaders must focus on creating a student experience that's well thought out, equitable, and cohesive.

Both faculty and staff will need to become more flexible and adaptive in order to respond rapidly to changing circumstances and students' needs. Faculty will need to become adept at remote teaching, learning, collaboration, and advising so that they can confidently revise and improvise in the moment.

Transforming Higher Education

The biggest transformation that institutional stakeholders are seeing now is a much broader collaboration between teaching faculty and the staff who support the curriculum, including academic technologists, instructional designers, and librarians. The most equitable level of access for all happens when faculty and staff are working together to improve the learning experience for students. As a result of this collaboration, faculty understand what other staff at the institution bring to the table, and staff become more involved in the classroom experience, physical or remote, and better understand what that experience is like for students and for faculty.

Increasing access and digital abundance for all students could help differentiate institutions in ways that could increase enrollments. The institutions that can achieve full and equitable digital access for students, often by forging new partnerships and taking prudent risks, will be more likely to survive—and succeed.

Issue #7: The Shrinking World of Higher Education or an Expanded Opportunity?

Developing a technology-enhanced post-pandemic institutional vision and value proposition

Steve Burrell, Joanne Kossuth, Joseph Moreau, and Nela Petkovic

"It matters what our students and our alumni do after they leave us. And it matters how they have the experiences that continue to give them the value—and not just in the networks and the conversations and ongoing learning opportunities, but to be able to really contribute, to help solve the problems we have as a society and as a world going forward using the skills we provide them with."

—Joanne Kossuth, Chief Innovation Officer, Mitchell College

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the changes that were already happening in higher education and pushed institutions faster and in new directions. Institutional leaders learned that they could deliver remote teaching and learning to their current students, and now many are ready to serve students across regions, countries, and the world.

Leaders at institutions ready to seize new opportunities are challenging themselves to expand access and increase students' outcomes by leveraging the experience they gained during the pandemic. Technology can help realize these ambitions more quickly and less expensively.

These leaders are also expanding their approaches to digital equity to encompass not only equitable access to connectivity and devices but also equitable access to learning spaces.

The institutions that are able to reassess their mission and strategies, embrace diverse thinking, create partnerships, accelerate their planning cycles, efficiently execute on their plans, and accurately measure the impact will thrive. Institutions that return to the status quo or slacken their pace will quickly fall behind.

Challenges in 2022

We are living in the in-between now. The pandemic continues, and the camaraderie and shared commitment that characterized the initial months of the pandemic has given way to an exhausted slog for many in higher education. For those who simply want to return to the way things were, the talk of permanent changes is frightening and exhausting. Faculty and staff may interpret plans for dual modes of working and teaching as plans to double their workloads. Yet some changes, such as remote work and flexible schedules, will be welcomed by most faculty and staff and in fact may be impossible to discontinue.

Numerous governments gave institutions additional temporary funding during the pandemic to make new investments that would help students and address equity and access issues. Institutional leaders will find it difficult to adjust to reduced funds while sustaining the improvements the support made possible.

Impacts on Culture

If higher education is to expand rather than shrink, people will have to stop viewing change as an occasional, timebound activity that the wily can avoid or subvert. They will have to stop appointing "change agents" as if only a few leaders need to take on that thankless role. Leaders and the workforce alike need to recognize that change is constant and involves everyone and that moments of stasis are brief and not always benign.

Signals of an unhealthy culture in higher education today include widespread agreement with statements like, "this is the way we've always done it," and "this is not what I signed up for." Institutional leaders need to help faculty and staff remember that what they actually signed up for is to serve students. Students' needs and expectations—even who students are—have changed dramatically.

Signs that the culture is adapting include being able to identify the services, processes, and structures that need to be discontinued in order to make way for a new institutional vision and value proposition. Other signs are a willingness on the part of faculty and staff to change the way they think about a sense of place and work and about who the students are.

Helping the Institutional Workforce Succeed

The institutional workforce cannot evolve until leadership evolves. Old "Newtonian"-era leadership principles that called for clarity of organization and one-dimensional measures of efficiency and productivity will no longer be sufficient to lead an evolving workforce through continued chaos and times of rapid change. What is needed is a new "quantum leadership" that incorporates emotional and spiritual intelligence to focus on helping all institutional community members advance the mission of higher education to serve both our society and the planet.Footnote10

But everyone, not just leaders, can and must lead from where they are. That requires investments in human resources, faculty, staff, and students in ways that encourage them to generate new ideas and be part of the solutions. Then leaders need to introduce those potential solutions to the institution, rather than to a specific silo, and allow them to either publicly succeed or publicly fail, because that's how the entire workforce will learn.

Recruitment, talent management, and work locations need to transform before institutions can. Applicants have greater leverage than they've ever had to set the terms of their employment. The current workforce expects more flexibility and options. Managers need to restore and even increase professional development and training to help prepare staff for new work and ways of working.

Needed Technologies and IT Capabilities

Technology leaders must rethink what infrastructure means in many different contexts. The infrastructure higher education needs must work well for remote learners and visitors. It must either extend beyond the campus to ensure that all learners have high-speed broadband access, devices, and spaces conducive to learning or it must adapt institutional services so that they work just as effectively for smartphones without high-speed access.

The new infrastructure needs to encompass digital experiences and interactions with the institution and deliver them as seamlessly and intuitively as, yes, Amazon. The concepts of consumer-focused infrastructure could also be extended to administrative and academic areas, such as the curriculum and the delivery of course materials.

As hard as technologists have worked over the last years and decades to integrate systems with each other, more progress is needed to achieve the levels of flexibility and seamlessness to which leaders aspire. The barriers are no longer technical; they are financial, political, and structural.

Many institutions still lack the tools and information required to make decisions quickly. Institutional leaders should ensure that they have the data and technologies that will enable them to measure the entire student life cycle, to inform decision makers about the effectiveness of new strategies, and to get accurate measures of strategic progress. Such tools include advanced prescriptive analytics for decision making, a well-developed marketing and enrollment management technology stack, and new tools for efficiently coordinating the evolution of curriculum.

Transforming Higher Education

The way higher education certifies learning and graduates is one of the most transformational opportunities. Institutional collaborations that enable students to attain and easily transfer credentials among multiple institutions would be a major advance toward that Amazon-like postsecondary educational experience. Beyond that, employers have been clamoring for clearer information about what graduates know and can do with their education (e.g., competency-based certifications). An associate's, bachelor's, or master's degree is not specific enough to enable employers to evaluate talent for the needs of their companies. If institutions, or the higher education sector as a whole, can clarify learning objectives and accomplishments in ways that advantage graduates and help employers, the value proposition of higher education will increase significantly.

Transformation is attainable, providing institutional leaders have the vision, political will, and ability to change. If not, their institutions may not continue to exist or may exist on the margins and become increasingly irrelevant. This moment matters. Students and alumni need to gain educational experiences and skills that will enable them to immediately contribute to helping solve our societal and world problems going forward.

Issue #8: Weathering the Shift to the Cloud

Creating a cloud and SaaS strategy that reduces costs and maintains control

Paul Harness, Shana Sumpter, Thomas Trappler, and Raimund Vogl

"We are transforming the backbone. We now have one cloud-based instance for all our Blackboard use, which was incredibly resilient when we had to move everybody, in the course of a matter of days, to all-online. Our contract required Blackboard and Amazon Web Services to just scale up. We didn't have to run around and buy a bunch of servers and whatnot."

—Mark Hagerott, Chancellor, North Dakota University System

Cloud computing has many potential benefits. When effectively deployed, cloud services can free up existing resources, enable institutions to scale up and down as demand changes (while paying only for the resources they are using), avoid in-house hardware and software expenses, and in some cases, enjoy increased reliability and security.

To realize the potential benefits of cloud computing, institutions need a cohesive strategy focused on effective coordination of the use of cloud services across departments and on effective management of contracts and supplier relationships.

Challenges in 2022

The adoption of SaaS products accelerated during the pandemic as academic and administrative leaders rushed to transition to online learning and remote work. The need to maintain business continuity prevailed over the need to plan and to mitigate risk through appropriate cloud contract terms. The consequences may need to be addressed in 2022.

Now that many institutions have adopted cloud or SaaS solutions, some suppliers are changing licensing models in ways that dramatically increase costs and are leveraging their market dominance to expand their cloud service models into more markets. Institutional leaders are struggling to negotiate affordable prices and sufficient privacy protections. Even those who participate in demand aggregation—in which state systems or even entire regions negotiate as a single bloc—are struggling to realize even modest discounts. As has long been the practice of solution providers, pricing is a black box that varies from contract to contract.

Some institutions are exploring alternative models that bring challenges of their own. For example, some college and university leaders in Germany are considering adopting an on-premises cloud architecture to preserve digital sovereignty, avoid an over-reliance on proprietary systems, mitigate financial risks, and adhere to the emphasis by the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) on controlling one's digital destiny. But even those institutions usually have to compromise digital sovereignty when it comes to consumer-level storage, productivity, and creativity software because their end users depend on these applications, with no feasible alternative.

General users can be an additional source of challenges. Staff adopting SaaS cloud products for business units quickly learn that these solution providers are rarely willing to customize their products to fit specific processes. Instead, institutional staff need to adapt the ways they work to fit the products.

Individuals may also inadvertently create security and licensing difficulties for an institution. Any individual can easily download software from the web and begin using it, without understanding whether the software is secure or how users' data and identities are being utilized and shared. Department staff may purchase cloud-based software to address business needs, only later learning that it may not meet institutional security requirements or be easily integrated with institutional applications and infrastructure.

Impacts on Culture

The successful adoption of the cloud entails a broad set of implications, ranging from meeting business needs to complying with policy and the law to realizing that the benefits of cloud computing depend on effectively addressing the associated risks. A key way to accomplish a successful cloud adoption is to establish and manage effective cloud contract terms and conditions. Achieving this requires a strong partnership among those in the procurement, cybersecurity, and legal departments, business process owners, and other key stakeholders to ensure that there are clear and equitable terms and conditions in the cloud contract.

In some cases, mindsets need to expand beyond an institutional focus. Leaders committed to operating technologies on-site rather than contracting with solution providers may choose to adopt a collaborative approach and share cloud services delivery across a district system or even a country.

Helping the Institutional Workforce Succeed

Adopting cloud computing is not just a technical activity; it is also a procurement activity.

To maximize the value and mitigate the risks of cloud computing, IT and/or procurement staff should gain skills in strategic sourcing, cloud contract negotiation, contract management, and supplier relationship management. Purchasers must be able to understand the contract and what they are actually receiving and are committing to.

Researchers using the cloud for very large storage and compute capacity will need significant technical skills, which many possess. Those who don't will need to rely on IT staff in their labs, departments, or the central IT organization for assistance and support.

Needed Technologies and IT Capabilities

The necessary technologies and capabilities differ depending on how an institution is using the cloud. Those institutions that are primarily adopting IaaS (infrastructure as a service) will be using Amazon Web Services, Microsoft Azure, or Google Cloud Platform. Staff at those institutions will have to adapt their skills and work routine to manage IaaS. On the other hand, institutions using cloud technologies for their own service delivery will need staff with a good understanding of mostly open-source technologies such as OpenStack and Kubernetes and a mindset for agile operations (including continuous integration / continuous deployment).

In all cases, institutions need to have a security and privacy strategy. Endpoint protection platforms, two-factor authentication, and cloud monitoring tools are some of the technologies that IT staff use to protect institutional data and individuals' identities.

Transforming Higher Education

Cloud adoption is still maturing. IT leaders and staff and cloud providers are all still learning and exploring new possibilities. In many ways, cloud computing has exacerbated long-standing tensions over costs and control between institutions and suppliers. Transformation may be an overly ambitious expectation of technology infrastructure and services provisioning. However, the increased agility enabled by the effective deployment of cloud services is significant and may contribute to a foundation for enhanced institutional innovation and efficiency. Agility enables leaders to try something new, fail fast (as needed), and try again until they get it right.

Issue #9: Can We Learn from a Crisis?

Creating an actionable disaster-preparation plan to capitalize on pandemic-related cultural change and investments

Joseph Moreau, Michelle Rakoczy, and Shana Sumpter

"We need to be flexible enough to pivot. I don't think this is the last pandemic we're going to see. I think climate change itself is going to produce more pandemics. So, we're going to need to be flexible in that way."

—Jeff Rafn, President, Northeast Technical College

It is usually only after a crisis that we learn the importance of anticipating and preparing for disasters. Although most higher education institutions had disaster recovery and business continuity plans in place before the COVID-19 pandemic, leaders at many of these institutions had not sufficiently rehearsed their plan. The pandemic showed the importance of rehearsal, helped leaders see what facets of their plans were insufficient, and required institutions to invest in new technologies, processes, policies, and working arrangements. The pandemic also showed whether institutions had strong relationships with solution providers and thus could rapidly negotiate affordable additional services and accommodations. Institutional leaders need to take the lessons they've learned over the last eighteen months and repurpose them for an ever-changing environment and for many different types of crises.

Challenges in 2022

Now is the time to adapt the institutional disaster-preparation plan to capitalize on pandemic-related achievements and to prepare for a variety of crises. But institutional staff lack the stamina to accommodate additional work. They are overwhelmed by continuing to live with the pandemic, and many of them long for equilibrium instead of having to constantly adapt as the public health situation morphs.

Impacts on Culture

Adapting disaster recovery and business continuity plans requires institutional leaders to determine their post-pandemic culture and practices so that these plans can be based on normal operations. But what will "normal" be? For many leaders, the answer is obvious: normal builds on pandemic learnings and investments. But many others still expect the post-pandemic normal to mirror the pre-pandemic normal. Updating disaster preparations may force this issue before some leaders are ready to address it.

Whether leaders are ready or not and admit it or not, the pandemic has transformed their institutions. Students found out about their ability to learn independently and remotely. Faculty found out about their ability to teach effectively with remote instruction and to use technology in new ways. Staff found out about their ability to improve both their productivity and their connection to their families while working remotely. Digital transformation got a big boost. Many institutions made gains in student engagement, equity, access, creativity, and innovation. Leaders now need to work with the institutional community to decide what to take forward and how and what to leave behind. These choices will define the institutional culture going forward.

Helping the Institutional Workforce Succeed

Communication makes everything work better. The lack of communication often contributes to, or even causes, failure. One reason staff have been so successful in managing the pandemic crisis is their relationships and lines of communication. Leaders need to continue that communication and develop those relationships in remote and hybrid working environments, whether those environments become an ongoing fixture of the institution or are only part of a business continuity plan.