Upheavals in work location and environment during the COVID-19 pandemic are challenging the higher education technology workforce.

As the COVID-19 pandemic upends higher education in 2020, institutions are relying on digital alternatives to missions, activities, and operations. Challenges abound. EDUCAUSE is helping institutional leaders, IT professionals, and other staff address their pressing challenges by sharing existing data and gathering new data from the higher education community. This report is based on an EDUCAUSE QuickPoll. QuickPolls enable us to rapidly gather, analyze, and share input from our community about specific emerging topics.1

The Challenge

Since workplaces are off-limits, home is the new office—as well as the new school, gym, and clinic. The ways of teaching, learning, and working used in higher education in January won't cut it anymore. But classes are in session, students need to complete their courses (and degrees), and prospective students need to be courted, notified, enrolled. Technology continues to be really, really important and useful. But it is also the lifeline that colleges and universities need in order to keep operating. The technology workforce is now essential to the future of higher education. And they, as individuals, are going through all the same changes as everyone else. How are they doing?

The Bottom Line

Most of the survey respondents are working remotely and getting their work done.2 Although the work itself hasn't changed much, workloads have increased, especially for IT leaders and people supporting teaching and learning. Most people have the technologies they need to work and to handle sensitive data, but many are struggling to maintain their physical, social, and emotional health. On the other hand, the newfound widespread ability to work productively from home is a silver lining, and respondents hope it can continue after the severe isolation of the pandemic eases.

Higher education institutions have had to change their cultures abruptly. Many respondents observed faster decision-making, greater focus, more collaboration, and more willingness to experiment and innovate. Straitened circumstances are eliciting greater compassion from colleagues and leaders and are resulting in more flexible work environments. Technology professionals hope all of these changes will continue beyond the pandemic. Respondents also discerned signs of digital transformation, as the pandemic forces broad changes in institutions' operations and strategic directions. Many respondents also fear a darker future that includes budget cuts and job losses.

The Data: Work, Location, and Workload

Most people are working remotely and getting their jobs done. Eight in ten people in the higher education technology workforce reported that they are working entirely remotely and are fulfilling all or most of their job responsibilities. This varies somewhat by job. Over 85% of people working in the following areas reported being able to fulfill all or most of their responsibilities: administrative/enterprise IT; applications development or operations; data, analytics, and business intelligence; design, media, and web; information security and services; and research computing and data.

Another 10% of the technology workforce are doing some work on campus and some remotely. The roles in which more than 10% of respondents said they were blending remote and on-campus work were IT operations and service delivery, networks and systems, and desktop services, client support, and IT service management. More than 10% of managers, institutional CIOs, and CIOs of departments, divisions, or schools within the institution are also blending remote and on-campus work.

A few individuals (3%) are still working entirely on their campuses, and 7% of the technology workforce are working remotely but are able to fulfill only some of their job responsibilities via their remote work.

The work itself has not changed much or at all for most people. Only 8% of respondents reported that their job responsibilities or the nature of their job had changed significantly. Significant job changes were most common (15%) among people working in academic and instructional technology. One in four survey respondents reported some changes, and over two-thirds (68%) said their job had not changed.

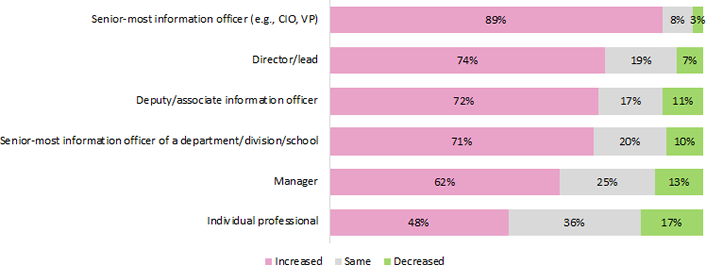

Most people have heavier workloads. Almost two-thirds (65%) of respondents said their workload has increased somewhat (38%) or greatly (23%). The higher the job level, the greater the proportion of people who reported increased workloads (see figure 1). Those in academic computing and instructional technology are experiencing the greatest workload increases (81% of respondents in that role).

These patterns of change in work, work locations, and workload are consistent for all institutional types.

Note: Some bars sum to more or less than 100% due to rounding

The Data: The Impact on People

Work environments are drastically different. Of course the work has not simply moved off campus; it has moved to homes. For some individuals, the home environment may be idyllic:

- "I'm far more productive working remotely in a pleasant environment than in an old building with an office over an autoclave."

- "I enjoy the quiet—our office environment is cubicles."

- "My work hours are basically 24/7. This does not mean I work 24/7, but I'm available to help users. During pre-COVID-19 this meant that I had to work 9 hours at an office and then be ready to help after hours. Now life is balanced. I still am available 24/7 but have the balance in life to live a life. I spend time with family during prime hours of the day such as lunch. I can take longer breaks and accomplish tasks that normally I may have been too tired to do once I'd gotten home from a 9-hour workday. All the while it seems I'm getting more work done (i.e., # of incidents handled) in a given 24 hours."

But for others, it may be chaotic and stressful as the boundaries between work and home disappear:

- "My husband and I are working full-time from home with a very active toddler who essentially needs to keep himself occupied for 8+ hours of the day. As a parent, I find it beyond difficult to watch my child suffer because I cannot give him attention during the day due to work."

- "Working at home has distractions that we just didn't have at the office. For example, between answering questions 10 and 11 on this survey, my wife and I had to take care of a (live, scared, and confused) squirrel that one of the cats had brought into the house (and then released for his enjoyment). So, that was fun. (The squirrel is now outside, where a different cat killed it, then brought the now-dead squirrel onto the porch for us to see, and I had to toss it into the bushes.) This happens less frequently on-campus."

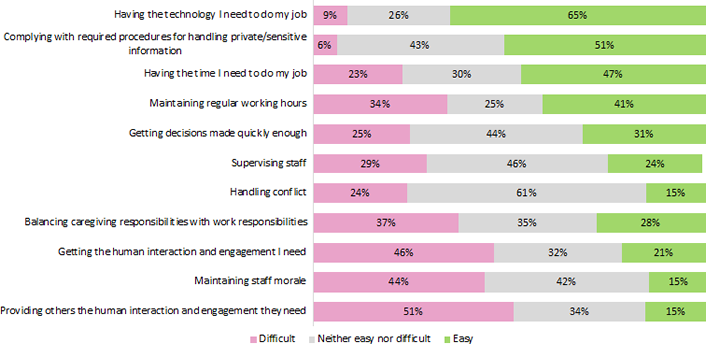

The situation is emotionally difficult. Most respondents said they have the tools and time they need to do their jobs, but almost half are having difficulties giving and getting enough human interaction and engagement or (for supervisors) maintaining their staff's morale (see figure 2). Many people have caregiving responsibilities and are having trouble balancing those with their work responsibilities.

How easy or difficult has it been for you to address each of the following during the pandemic?

Note: Some bars sum to more or less than 100% due to rounding

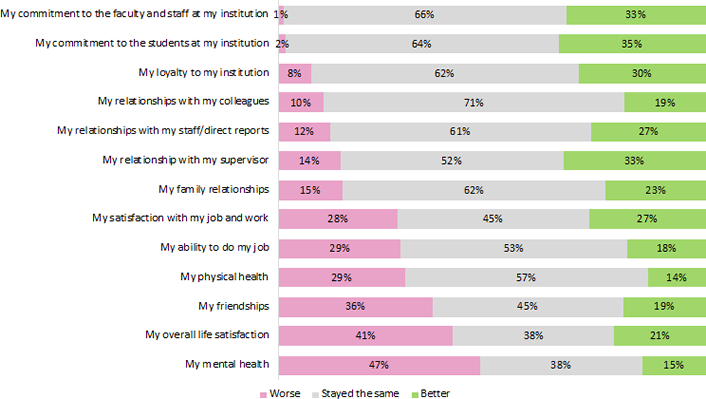

The pandemic is taking its toll. The work has not just shifted off-site: people are often working in very isolated conditions, without physical access to friends, extended family, care providers, places of worship, or gyms. In the survey comments, some people expressed their fear and anxiety about the pandemic, possible layoffs, and their mental health. The data show that many are struggling to maintain their physical, social, and emotional health (see figure 3). Overall life satisfaction has worsened for about four in ten people (41%).

Some things are getting better. Although most people reported no change in their commitment levels, 30–35% said their commitment to faculty, staff, and students and their loyalty to their institution has improved. From our qualitative analysis of the survey comments, this is very likely because technology workers reported that faculty, staff, and institutional leadership have a stronger or newfound appreciation of the IT workforce and of the value of using technology to teach and work. Many people expressed their delight that students were the focus of institutional attention and investment.

How have the following changed since the pandemic began?

Note: Some bars sum to more or less than 100% due to rounding

Promising Practices

The pandemic is causing widespread fear, grief, and deprivation. Everything has changed. We all know that work and life will be different after the pandemic. When asked for suggestions on how to improve higher education afterward, those in the technology workforce did not lack opinions about how today's disruptions can benefit colleges and universities, workplaces, and people. Over 1,800 of the survey's 2,695 respondents described the work changes they hope will continue after the pandemic eases.

The toothpaste is out of the tube: remote work works and should continue. Over half of the 1,800 comments advocated for continuing remote work. Individual professionals felt they had proven that they can be at least as productive working remotely, most work can be done off-site, and staff and faculty now have the tools and ability to work off-site, at least part of the time.

Greater compassion and support for work-life balance increases workforce engagement. Although no one is enjoying the pandemic, almost 200 people reported what one respondent described as a "widespread recognition of the need for compassion and flexibility." Another respondent hoped that "understanding and empathy for people's personal lives, mental health, varying abilities, and limitations" would survive the current crisis.

Values to keep: focus, communication, collaboration, and transparency. Institutional leaders have a clear and shared priority: maintain educational and operational continuity during the pandemic. That universal priority is collapsing silos. The need to act quickly is instilling a sense of urgency and need to communicate. Respondents wrote that they are seeing the following:

- "Stronger relationships and collaboration with faculty"

- "More pragmatic approaches and easier collaboration between units"

- "People's willingness to work together to solve problems"

- "Partnership with chairs and deans"

- "Greater coordination between offices, currently due to our shared focus on online learning and working. Perhaps for the future, we can find other common foci, so we don't have too many competing priorities that make coordination more difficult."

- "Sense of common cause among colleagues; willingness to help across divisions"

The pandemic is accelerating digital transformation. Respondents reported signals of digital transformation across their institutions. EDUCAUSE has described the culture, workforce, and technology shifts that accompany digital transformation (Dx),3 and those shifts are occurring rapidly in reaction to the massive changes that colleges and universities are being forced to make.

- "I see faster decision-making on critical issues. This has forced our institution to make overdue cultural changes."

- "The pandemic has shown that a broad spectrum of stakeholders can come together to make quicker decisions and enable actions to proceed to support the mission."

- "Innovation and agility. More comfortable with 'safe to experiment' exercises: try something, and if it does not work, we try something else."

- "The push to leverage existing technology resources/investments; the drive to modernize and streamline business processes"

- "The pandemic has required all work to be digitized, with archaic workflows abruptly modified."

- "There is a certain sense of optimism coupled with positive attitudes about digital transformation."

As one respondent wrote, "I hate living through history, but the alternative is worse." We are all living through history right now. The higher education technology workforce is no monolith. Everyone has unique circumstances, gifts, and challenges. Today's stresses are bringing some people to the edge of despair and some institutions to the brink. Yet the seeds of the future have been planted. As individuals and institutions eventually emerge from the current crisis, all will have an opportunity to create more flexible, caring, and collaborative workplaces and more innovative, focused, and agile institutions. The seeds will germinate if we tend to them.

EDUCAUSE will continue to monitor higher education and technology related issues during the course of the COVID-19 pandemic. For additional resources, please visit the EDUCAUSE COVID-19 web page. All QuickPoll results can be found on the EDUCAUSE QuickPolls web page.

For more information and analysis about higher education IT research and data, please visit the EDUCAUSE Review Data Bytes blog as well as the EDUCAUSE Center for Analysis and Research.

Notes

- QuickPolls are less formal than EDUCAUSE survey research. They gather data in a single day instead of over several weeks, are distributed by EDUCAUSE staff to relevant EDUCAUSE Community Groups rather than via our enterprise survey infrastructure, and do not enable us to associate responses with specific institutions. ↩

- The poll was conducted on April 22, 2020; 2,695 people responded. The poll consisted of thirteen questions. Median completion time was 4 minutes 46 seconds, pushing the boundaries for QuickPoll length. Poll invitations were sent to participants in various EDUCAUSE community groups. Most respondents (2,573) represented US institutions. Other participating countries included Australia, Canada, Europe (unspecified), Finland, Germany, India, Ireland, Jamaica, Japan, Kenya, New Zealand, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. Respondents came from a wide range of jobs (the QuickPoll used the EDUCAUSE IT Workforce Research job families): Academic computing/instructional technology (426); Administrative/enterprise IT (337); Applications development or operations (173); Data, analytics, and business intelligence (76); Design, media, and web (84); Desktop services/client support/IT service management (336); Information security and services (108); IT executive leadership (422); IT operations and service delivery (238); Networks and systems (157); and Research computing and data (40). "Other" was selected by 287 respondents. Many of these were IT project managers, business office staff, faculty, and people whose jobs covered multiple job families. 11 people did not select a job family. Respondents also varied by job level: 1,200 individual professionals, 489 managers, 541 directors, 123 deputy/associate CIOs, 102 departmental/division/school CIOs, and 222 institutional CIOs. 18 people did not select a job level. Respondents' institutions varied by Carnegie classification and institutional size, neither of which was associated with differences in the pattern of responses. ↩

- Malcolm Brown, Betsy Reinitz, and Karen Wetzel, "Digital Transformation Signals: Is Your Institution on the Journey?," Enterprise Connections (blog), EDUCAUSE Review, October 9, 2019. ↩

Susan Grajek is Vice President of Communities and Research at EDUCAUSE.

© 2020 Susan Grajek. The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 International License.