Staff have experienced, and will continue to experience, increased levels of stress at work. Awareness of the contributing factors and the mitigating supports can help institutions and leaders better ensure staff well-being in the future.

EDUCAUSE is helping institutional leaders, IT professionals, and other staff address their pressing challenges by sharing existing data and gathering new data from the higher education community. This report is based on an EDUCAUSE QuickPoll. QuickPolls enable us to rapidly gather, analyze, and share input from our community about specific emerging topics.Footnote1

The Challenge

In her Chronicle of Higher Education article "The Staff Are Not OK," Lee Skallerup Bessette lamented higher education's lack of attention to staff well-being in the days of COVID-19.Footnote2 In institutions' scramble to move courses online and upend traditional models of operation, the staff have continued to work tirelessly to keep their institutions afloat, often at the expense of their own mental and physical health. In this week's QuickPoll, we check in with more than 1,500 higher ed IT and technology professionals to see if they're OK, gauge the sources and impacts of their stress, and explore opportunities for individuals and institutions to ensure improved well-being on the road ahead.Footnote3

The Bottom Line

The staff have, in fact, not been OK and may not be for some time. Strong majorities of respondents reported increases in stress since the beginning of the pandemic and expect their stress to persist or even worsen over the next year. Staff are being called upon to take on more work with fewer resources, and the effects of these and other stressors are manifesting in diminished workplace experiences and productivity. Institutions can help by offering their staff flexibility and supportive leadership, with an intentional focus on listening, empathy, and healthy boundaries.

The Data: Why Are We So Stressed?

Newsflash—the staff are stressed out. Though perhaps surprising to no one, and yet no less important to acknowledge, a strong majority of respondents (76%) reported that their level of workplace stress has increased since the beginning of the pandemic. This figure is even higher among professionals focused on supporting remote teaching and learning, including respondents in academic computing or instructional technology (86%) and in instructional design or faculty development (81%). Nearly a fifth of all respondents (19%) reported that their level of stress has remained about the same, and only 6% reported that their level of stress has decreased.

The year ahead will be more of the same, if not worse. Few respondents expect relief from stress on the road ahead. Asked about their anticipated level of stress over the next 12 months, more than half (54%) of respondents said they expect their stress to stay about the same as it is now. More than a third (36%) expect their level of stress to increase even further over the next 12 months, while just 10% expect their stress to decrease.

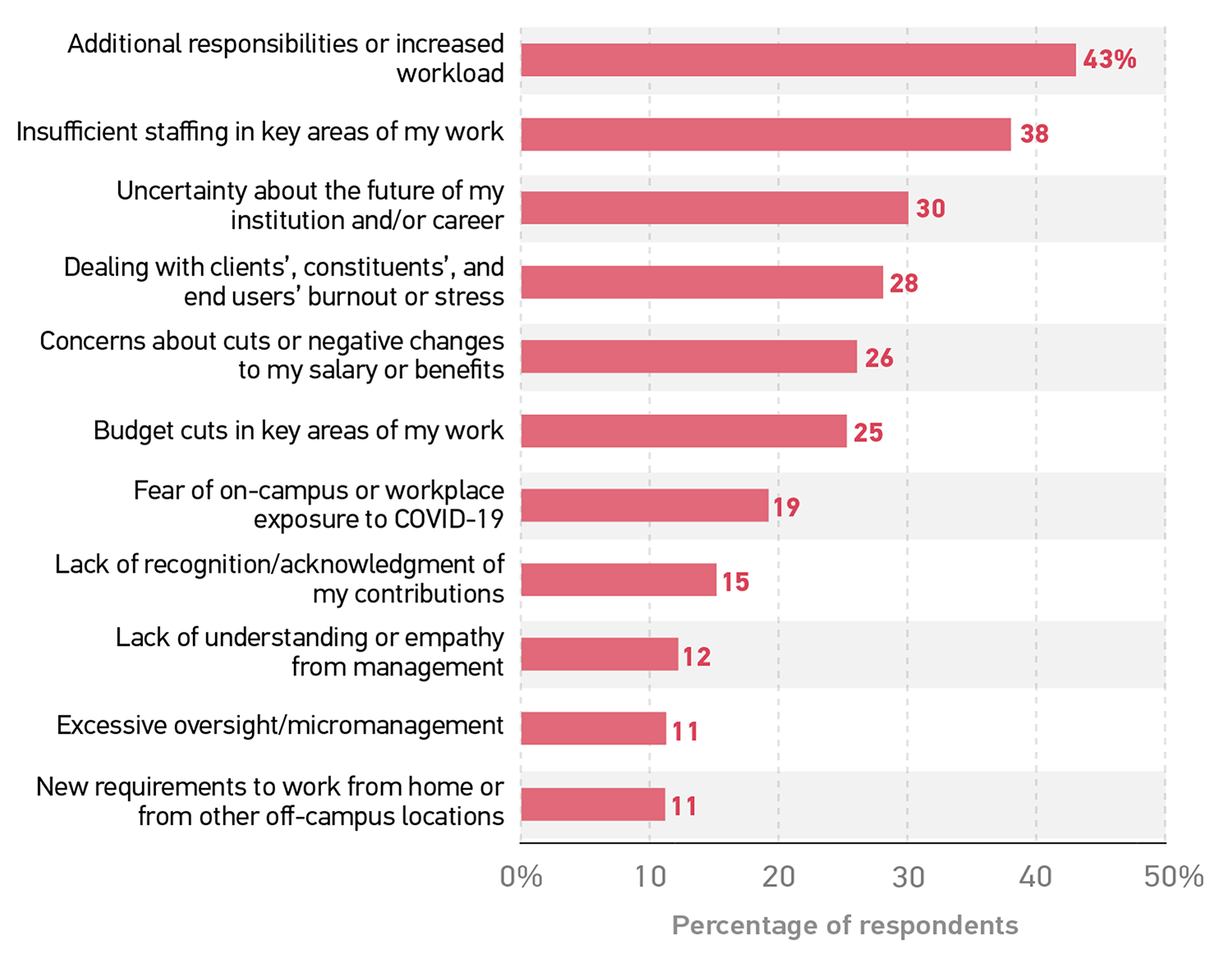

Staff are doing more work with fewer resources and less certainty. Why are the staff not OK? Asked to select the top workplace factors contributing to their stress over the past year, respondents' two most popular choices were "additional responsibilities or increased workload" (43%) and "insufficient staffing in key areas of my work" (38%). This finding supports the narrative, highlighted in previous QuickPolls, that many staff have been called upon to do more with less,Footnote4 and it illustrates that this combination of factors remains a critical challenge (see figure 1). "Uncertainty about the future of my institution and/or career" (30%) rounds out the top 3 stress factors. This particular source of stress appears to be significantly more prevalent among respondents from the smallest institutions—36%, compared with only 27% among those at the largest institutions.

The Data: What Is Our Stress Doing To Us?

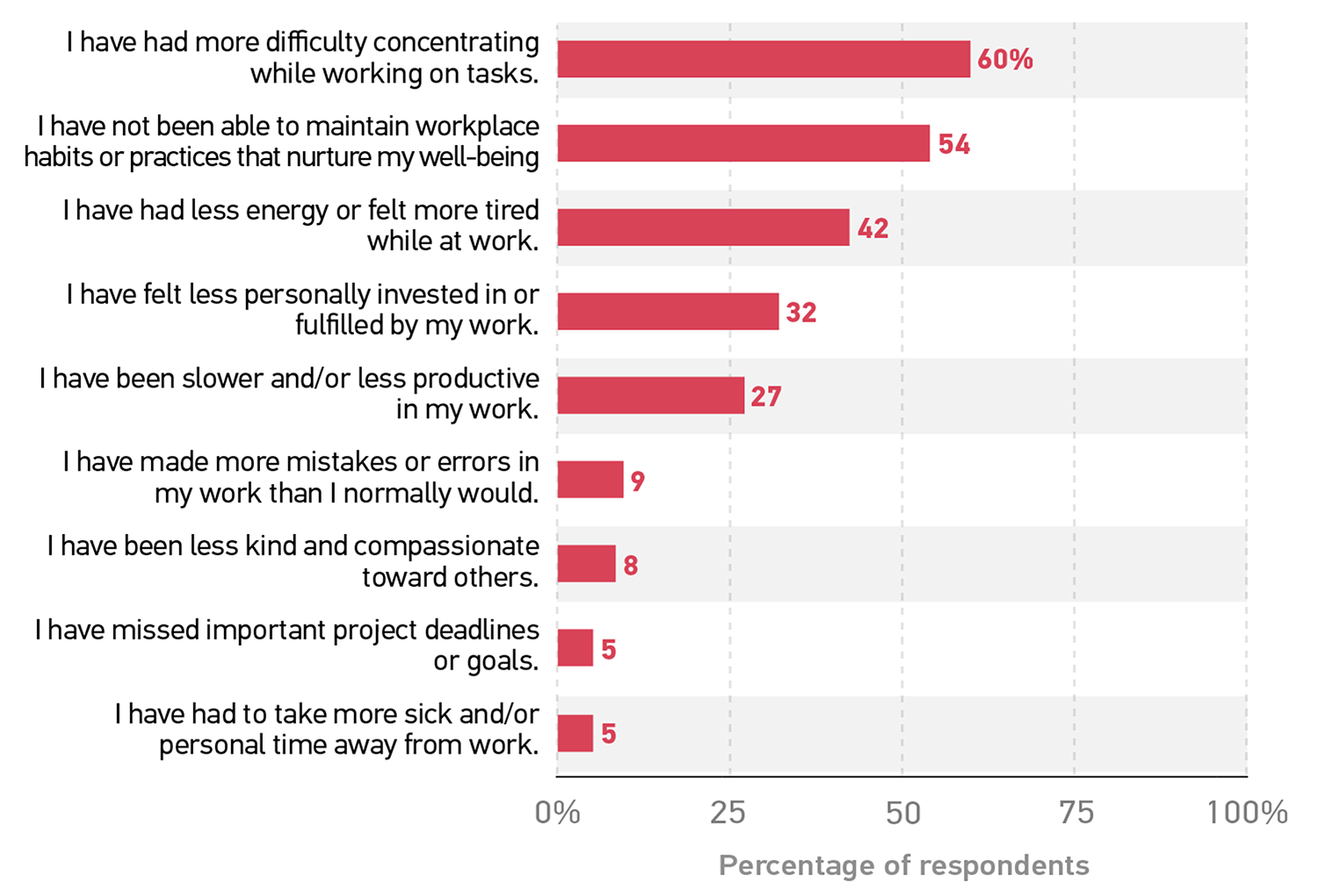

Staff focus, well-being, and energy at work are suffering. Staff stress isn't benign and indeed is negatively impacting work. Asked about the primary impacts of stress on their work, 60% of respondents indicated that they have had difficulty concentrating on tasks as a result of their stress, and 54% indicated that they haven't been able to maintain workplace habits or practices that nurture their well-being (see figure 2). Smaller, but not insignificant, numbers of respondents selected impacts indicating a general difficulty in continuing to "show up" and do their work—having less energy or more exhaustion at work (42%), feeling less invested in or fulfilled by their work (32%), and being slower or less productive in their work (27%).

The Data: What Are Institutions Doing, and Why Does It Matter?

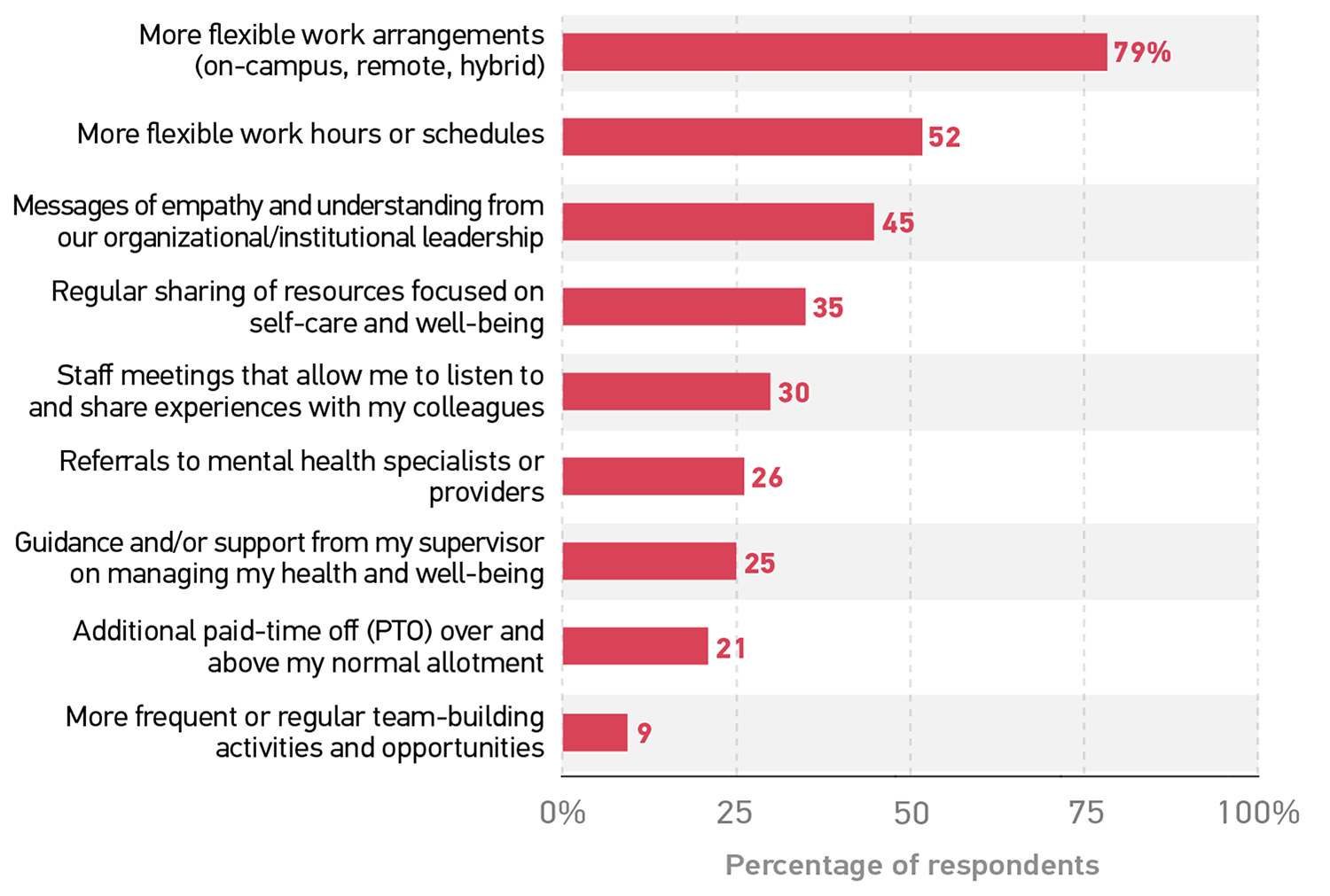

Institutions are providing flexibility, but supervisory guidance and team-building are lacking. Far and away the most common support that institutions provided to respondents was "more flexible work arrangements" (79%) (see figure 3)—perhaps not surprisingly, given last year's migration of many staff to remote modes of working.Footnote5 A majority of respondents (52%) reported that their institution has provided more flexible work hours or schedules, and just under half (45%) reported receiving messages of empathy and understanding from their leadership. Only a quarter of respondents reported receiving guidance or support from their supervisor for managing their health and well-being, while roughly a fifth reported receiving additional PTO from their institution. Very few (9%) reported having more frequent or regular team-building activities or opportunities.

Institutional support matters for mitigating future stress. Approximately 6% of respondents told us that they have received none of the above supports from their institution.Footnote6 Among those, 56% expect that their stress is going to increase in the year ahead. This figure drops to 40% among respondents receiving even just one of any of the above supports from their institution. Among the supports, those related to flexibility and the role of supervisors/leadership seem particularly helpful for improving staff outlook on the year ahead. As summarized in table 1, when any of these supports is present at the institution, respondents are significantly less likely to expect their level of stress to increase in the year ahead.

Table 1. Outlook for workplace stress, by presence of institutional support for staff

| Support Type | Percentage Expecting an Increase in Stress over the Next Year | |

|---|---|---|

| When Support Is Absent | When Support Is Present | |

|

Flexible work arrangement |

42% |

33% |

|

Flexible hours/schedule |

40% |

30% |

|

Supervisor guidance on health/well-being |

38% |

27% |

|

Messages of empathy or understanding from leadership |

40% |

28% |

Common Challenges

In the course of reflecting on constructive paths forward, respondents also expressed frustrations and challenges that seem to be shared widely across the higher ed community.

- Workloads and expectations of staff have not been adjusted to fit new realities of constrained and even shrinking resources (human, financial, or otherwise) with which to get the work done.

"Now that things have settled a bit…and most courses are operating fine remotely, the workload hasn't decreased. Other things have taken that place, and we're still overworked. I guess overworked is our 'new normal.'"

- Many staff are feeling overlooked and expressed the desire simply for more acknowledgment or recognition from their leadership for the hard work they're doing.

"Better recognition (staffing, pay, or simple recognition of work performed), especially for good work done by understaffed offices."

- More transparent and frequent communication from leadership is critical for institutions especially during times of crisis, and many staff feel they're not getting that level of communication from their leaders.

"Communication has gotten worse during the pandemic, leading to confusion, animosity, and frustration. Clear communication is key."

Promising Practices

Respondents provided a number of personal strategies they've employed over the past year to help mitigate the stress they've experienced at work.

- Staff are finding relief in physical activities (going for walks, exercising) and mental activities (prayer, meditation) that momentarily disconnect them from work and help them feel refreshed.

"An increased focus on meditation, prayer, and acceptance. A daily gratitude practice has been critical as well."

- Perhaps especially in remote work environments, staff have found it helpful to continue finding ways of connecting with their peers and having meaningful conversations with the people they know and trust.

"After-work virtual cocktail socials with others in my field. Participating in more virtual conferences."

- Intentionality in establishing daily work routines and setting up clear boundaries around work have helped staff in reclaiming some "normalcy" and a healthier work/life balance.

"Having a routine and a regular place designated for work has helped me avoid stress during this time."

Respondents also provided recommendations specifically for their supervisors or institutional leadership to consider in supporting their staff and enabling improved workplace health and well-being.

- Provide flexibility for staff, both in terms of their working arrangements (on-campus, home, hybrid) and in their work hours and schedules. Consider flexibility as a long-term policy, even in a post-pandemic world.

"[Because I am] a single mother, flexibility is probably more important than even salary. I have a long commute, and the ability to work from home has greatly DECREASED my stress. I have an extra 3 hours in my day. This is huge. I'm more productive at home and have more time with my teenage kids."

- Establish healthy policies and boundaries for staff. Consider limiting the frequency and stacking-up of meetings, including agreed upon "no meeting" times. Limit evening and weekend email activity.

"I schedule meetings for 45 minutes rather than an hour and take the 15 minutes to walk away from my home computer. I also schedule walks outside twice each day for 20 minutes each."

- Listen to your staff. Practice empathy and seek to understand who they are and what they're experiencing.

"Display more empathy and understanding from the top. There is not much that can be done to make things measurably better, but knowing the leadership understands is helpful."

"Ask. Listen. Ask. Listen. Repeat."

All QuickPoll results can be found on the EDUCAUSE QuickPolls web page. For more information and analysis about higher education IT research and data, please visit the EDUCAUSE Review Data Bytes blog, as well as the EDUCAUSE Center for Analysis and Research.

Notes

- QuickPolls are less formal than EDUCAUSE survey research. They gather data in a single day instead of over several weeks, are distributed by EDUCAUSE staff to relevant EDUCAUSE Community Groups rather than via our enterprise survey infrastructure, and do not enable us to associate responses with specific institutions. Jump back to footnote 1 in the text.

- Lee Skallerup Bessette, "The Staff Are Not OK," Chronicle of Higher Education, October 30, 2020. Jump back to footnote 2 in the text.

- The poll was conducted on January 12, 2021, consisted of 10 questions, and resulted in 1,522 complete responses. Poll invitations were sent to participants in EDUCAUSE community groups focused on IT leadership. Our sample represents a balanced range of institution types and FTE sizes, and most respondents (96%) represented US institutions. Jump back to footnote 3 in the text.

- Mark McCormack, "EDUCAUSE QuickPoll Results: Fall Planning for Online and Physical Spaces," EDUCAUSE Review, August 7, 2020. Jump back to footnote 4 in the text.

- Susan Grajek, "EDUCAUSE COVID-19 QuickPoll Results: The Technology Workforce," EDUCAUSE Review, April 24, 2020. Jump back to footnote 5 in the text.

- This 6% of respondents were excluded from the denominator in the calculations for the data reported in figure 3. Jump back to footnote 6 in the text.

Mark McCormack is Senior Director of Analytics & Research at EDUCAUSE.

© 2021 Mark McCormack. The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 International License.