Incorporating play into course design can help students to feel more connected with their instructors and with each other, reduce stress, and prime students to engage in learning about emotionally heavy topics.

In today's workplace, there is a common perception that in order to be perceived as professional (and thus be taken seriously), and ultimately to be successful, we must always be busy to the point of being overworked, always appear serious, and never waste time. I think this message is wrong and fear-based—and it limits our effectiveness as professionals and especially as higher education faculty. I'd like to propose an alternative ethic: play.

I believe the societal beliefs about professionalism are deeply engrained in our culture and are communicated to us starting at a young age. However, the first time I was overtly confronted with these notions was as a faculty member. I quickly became disillusioned by the seriousness, stress, and formality of higher education. I began to wonder if I had wandered into a field that did not align with my personal values and if I would ultimately become burnt out. Then I found play—or maybe play found me—but I instantly felt invigorated and hopeful that maybe academia, or at least my classrooms, could be serious and professional and joyful and playful. That's when I knew that academia could be for me. I just needed to create my own narrative—a playful narrative. Since this play-awakening, I have spent years engaged in trial and error to bring play into my teaching. I've had successes and I've had some failures, but I have also started seeing that my students have become more engaged and invested in their learning.

In the spring of 2020, I conducted a research study on students' experience of incorporating play in learning. I quickly realized that even I had underestimated the power of play. Play has the ability to create connections and reduce stress. It is student-centered and humanistic and allows students to overcome their anxiety and their fear of being vulnerable. Play primes students for learning. It is a vehicle for the application of theory and the acquisition of new skills, and it results in longer-lasting learning.1 Perhaps the biggest take-away from the data is that play in learning is a bit like climbing the first step of a staircase before you're certain the next step is actually there.

Even when play doesn't seem to directly connect to the content of your course, it can still be the catalyst that ignites an invaluable learning process—one that you never would have experienced if you believed that play is trivial. Through my research, I found that play creates relational safety, removes barriers to learning, and awakens intrinsic motivation. Once play ignites these vital aspects, students become more engaged and learn on a deeper, more personal level.

Play in learning is a powerful process, but it has not been given much space in academic conversations. Therefore, a colleague and I founded a faculty email list in June 2020 called Professors at Play. We wanted a platform where playful faculty (or aspiring playful faculty) could share their ideas and experiences and be inspired to incorporate play into their own teaching. The email list began with only five members. As of this writing, the email list has 540 members.

Our email list was developed roughly three months into the coronavirus pandemic (in the United States). This timing was not intentional, but I wonder if the inception of the email list at this particular time is what prompted so many people to subscribe so quickly. I do not think everyone joined for the same reason. Some surely would have joined the email list before the pandemic. (Play in higher education is certainly not a new concept, but it is frequently misunderstood and underutilized.) Yet some faculty seemed to have joined to find something to help them get through the discomfort and uncertainty of teaching in a virtual environment during the pandemic. I wonder if the abrupt shift in instruction pushed some faculty outside of their comfort zones to the point where they felt lost in a sea of uncertainty, leaving them feeling drained and exhausted. Maybe for these faculty, the Professors at Play email list was one small resource that could provide some relief. Others may have joined our community because the timing was right to rethink their pedagogy. This shift to virtual course delivery may have provided an opportunity for faculty to fiddle with their teaching. COVID-19 may have pushed them to reconsider their pedagogical approach in these unprecedented times.

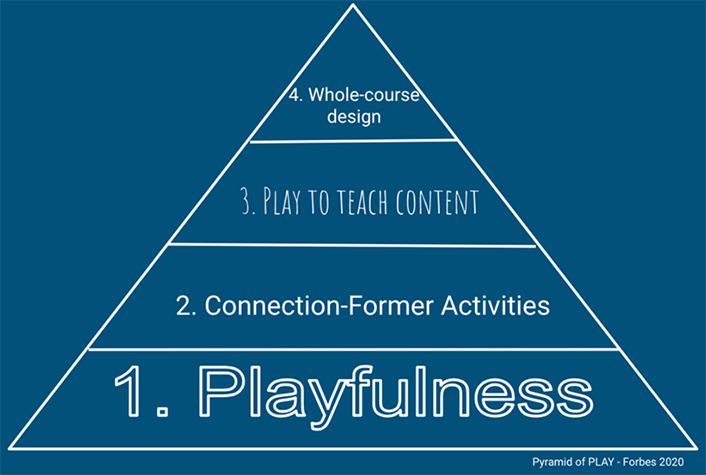

Whatever the reason why so many faculty are interested in Professors at Play, they often have similar questions: What do you mean by play in learning? How do I do that? I believe that play can take on many forms in teaching, but I conceptualize the different types of play as four levels of a pyramid (see Figure 1).

Playfulness

While being "playful" looks different for each person, I believe anyone's route to uncovering their professional playfulness should start with deconstructing and challenging the societal message that says, "To be professional, you must be serious." Once you release some of the societal shoulds about professionalism and the place of play in adulthood, you can then consider making your syllabi less formal and more playful. You might add an element of creativity, surprise, or play to typically serious assignments. You might even consider ways of presenting yourself as more playful rather than as overly professional and serious. Breaking out of the status quo of "professionalism" will definitely feel uncomfortable at first, but the degrees of playfulness are all on a continuum, so make small changes at first. I tell my counseling students that presenting themselves as overly professional and serious counselors will not help them to create a strong therapeutic alliance with their clients. The same thing goes for teaching. If we as faculty have the courage to be more playful, our students will be better able to connect with us and with each other. When students feel connected with their instructors and with each other, they become more invested in the content.

Connection-Former Activities

One way to incorporate play into your classes is to use what I refer to as "connection-former" activities. You probably know them as ice-breakers. I don't like the term "ice-breaker" because it seems to have a negative connotation, which may lead faculty to underutilize them. Connection-former exercises are play activities that are intended for the sole purpose of creating joy, levity, stress reduction, laughter, and connection. Faculty usually shy away from this type of play because they don't know (or trust) the hidden power of play—especially when the play initially appears irrelevant to their course content. Not only does play for the sake of fun help to connect people and build relationships between them, but it also reduces stress and primes students to approach difficult or heavy class content. The content areas I teach—child abuse, sexual assault, mental illness, suicidal and homicidal ideation, etc.—are emotionally heavy. Silly play does not trivialize these topics; it simply makes them easier to approach. While I never use silly play to teach heavy concepts directly, play for the sake of fun takes up a few minutes at the start of class and has an astounding impact on students' openness to approach the seriousness of the topics.

Play to Teach Content

Designing play to directly teach content takes a little more creativity and thoughtfulness, but it might be easier than you think. You can take a discussion or activity that you already use in your classes and add an element of game design, competition, or surprise to make it more playful. For example, when I notice the group discussions are dying down, I provide the last prompt and ask groups to generate some type of "product" from their discussions. The product can be anything from a list and a subsequent acrostic to a two-sentence theory for something that has more than one possible answer or a metaphor for a concept. Each group then shares its product, and all students vote on the best, funniest, or most creative. Each person in the winning group gets a prize. This is just one example. My students have learned that I will throw in something like this at the end of a discussion or activity, and I have noticed they are more engaged in discussions as a result.

Whole-Course Design

The top level of my pyramid of play—whole-course design—is the most challenging to do. It requires the most time and creativity to develop as it spans the entire course. I have not yet figured out how to execute it for my classes. In fact, I have only seen one example (to my knowledge) of play in whole-course design. Roberto Corrada, a featured speaker at the upcoming Professors at Play Playposium and a professor of law at the University of Denver, utilizes a whole-course indeterminate simulation in his administrative law class. Corrada asks his students to read the book Jurassic Park, and throughout the rest of the course, they are tasked with designing regulatory strategies and laws for extinct animal parks. The genius of this application of whole-course play is that the students cannot apply or refer to any existing laws in their work because laws for extinct dinosaur parks don't exist.

To learn about Corrada's approach and get ideas for incorporating play at any of the levels on my pyramid of play, consider dropping into the Professors at Play Virtual Playposium on November 6 from 8 a.m.–4 p.m. MST. I believe the coronavirus pandemic has been a catalyst for shifting how faculty and others in the higher education community think about teaching and delivering content. The number of members in the Professors at Play community demonstrates that faculty are looking for highly interactive, engaging, playful, and fun ways to deliver content online. Perhaps the pandemic has forever altered the trajectory of traditional education and paved the way for more faculty to value and explore play in higher education. I sure hope so. That would be fun.

Author's note: If you're interested in joining the Professors at Play email list, you can request to be added to our Google Group. Follow us on Twitter (@PlayProfessors), Instagram (@professors.at.play), or Facebook (@professorsatplay). You can also check out the Professors at Play website or register for the free Professors at Play Virtual Playposium, which will be held November 6, 2020, from 8 a.m.–4 p.m. MST. We have two amazing keynote speakers lined up, as well as many great play sessions and discussions led by members of our community.

For more insights about advancing teaching and learning through IT innovation, please visit the EDUCAUSE Review Transforming Higher Ed blog as well as the EDUCAUSE Learning Initiative and Student Success web pages.

The Transforming Higher Ed blog editors welcome submissions. Please contact us at [email protected].

Note

- The findings from my study have not yet been published. For more information, check out Alison James and Chrissy Nerantzi, The Power of Play in Higher Education: Creativity in Tertiary Learning (London: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, 2019). ↩

Lisa Forbes is an Assistant Clinical Professor at the University of Colorado Denver.

© 2020 Lisa Forbes. The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY 4.0 International License.