October is National Cyber Security Awareness Month (NCSAM). Throughout the month of October, EDUCAUSE will highlight higher education information security issues. This blog post is part of a series of entries published in the Data Bytes, Security Matters, and Transforming Higher Education EDUCAUSE Review columns focusing on faculty and student perceptions of information security research results from ECAR's 2017 Technology Research in the Academic Community.

Each year, the EDUCAUSE Learning Initiative (ELI) surveys the higher education teaching and learning community to determine the field's key issues. Without doubt, the perennial "keymost" issue in the set is faculty development: it was #1 in 2015, #2 in 2016, and back to #1 in 2017. And it enjoyed this high ranking across all institutional types, from community colleges to research institutions. Since faculty development is such a high priority for the teaching and learning community, any source of solid information about faculty attitudes is of keen interest and highly relevant. In this post, we'd like to call attention to an important report about higher education faculty, and to zero in on one of its findings about faculty attitudes regarding information security.

The report is the EDUCAUSE Center for Analytics and Research (ECAR) biennial study of faculty and information technology. The ECAR Study of Faculty and Information Technology, 2017 is based on an extensive survey of higher education faculty to track their experience in using digital technology. One section of the 2017 study focuses on the question of information security training for faculty. While perhaps not the most glamorous aspect of faculty development, as a dimension of faculty's IT experience, it looms increasingly large in importance. The importance of information security has been thrown into especially sharp relief by massive data breaches such as those of Equifax and Yahoo. Institutions of higher education have been specifically identified by the Department of Homeland Security and the Federal Bureau of Investigation as one of the types of organizations that were breached and used to host cyberattacks during the 2016 U.S. election cycle.1

The importance of information security is increased further by the growing volume of learning data that is passing through the "veins" of the campus IT network. Open standards for learning data, such Caliper and xAPI, have established a kind of "Esperanto" for learning data, meaning that any application supporting these standards can contribute learner data to campus aggregation, sometimes called a "learning record store." Add to that the emergence of integrated learner advising systems, which also draw on disparate sources to aggregate student data for advising purposes. As the volume of data tied to students' identities grows, so too does the need for good information security practices. Seen this way, security training for faculty is increasingly essential.

So what did the faculty, in their responses to the survey, have to say about their information security training experience? Here are a few the report's findings:

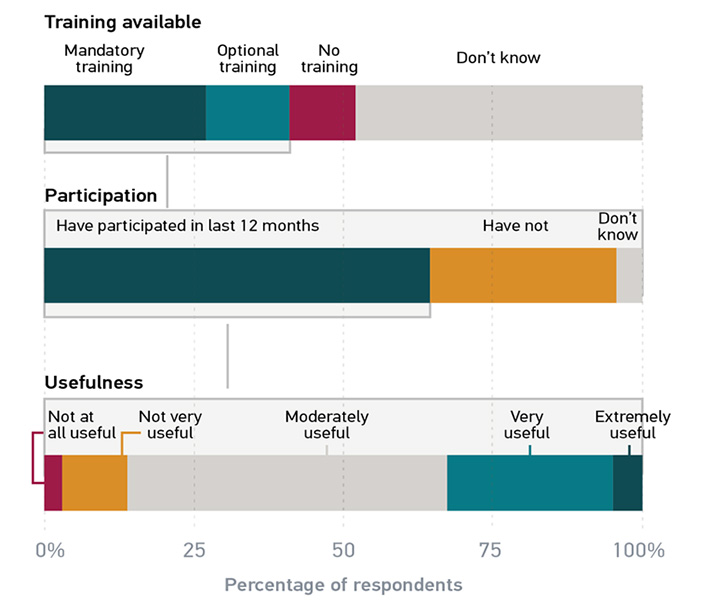

- About half (48%) of the faculty respondents did not even know if their institution offers information security training (see figure 1).

- Of those faculty who had participated in security training in the past year, 86% found the training to be at least moderately useful.

- Between two-thirds and three-quarters of the faculty expressed confidence in their institution's ability to safeguard information.

- More than three-quarters (76%) of faculty declared that they understood their institution's policies about data security.

Equally important is what the report reveals about what constitutes effective training for faculty. The faculty who did not find their training particularly valuable or useful were asked how it might be improved. This yielded, as the report rightly observes, "useful and actionable advice." First is what clearly doesn't work: these faculty expressed "quite intense dislike" of third-party videos. In the survey responses, according to the ECAR analysis, some faculty indicated that the videos were either outdated or too general to be useful, which no doubt exacerbated their impatience. These faculty further indicated that training that consisted of such videos came across as condescending—obviously not a good outcome. Indeed, the very term "training" connotes condescension, so calling your faculty development "training" is guaranteed to get you off on the wrong foot.

On the positive side, this section of the ECAR report concludes that information security training for faculty needs to be "customized to the audience" (and no doubt not just the training for faculty). Those designing faculty development programs in information security need to provide experiences that are delivered primarily in person and that utilize content that is clearly and directly relevant to their campus environment. As always, relevance is the key factor in all learning engagements, and faculty learning is certainly no different in that respect.

In these findings, we can see that faculty do not differ from anyone else who approaches the task of learning something. We know from learning research that people learn best when they are engaged (fueled best by the relevance of the material to be learned) and when the learning has an active dimension. So it's no surprise that some faculty expressed impatience when their training consisted of watching third-party training videos. Requiring or cajoling faculty to watch such videos is, ironically, a return to the transmission/lecture style of learning, and so is itself an outdated approach.

This peek into faculty learning preferences dovetails with the wider shift in the way faculty development is conducted, which is moving away from sets of siloed workshops and training sessions toward crafting programs that view the faculty as a community of lifelong learners.2

Notes

- Department of Homeland Security and Federal Bureau of Investigation, "GRIZZLY STEPPE – Russian Malicious Cyber Activity," Joint Analysis Report JAR-16-20296, December 29, 2016.

- A good read on these new developments with respect to faculty development is Envisioning the Faculty for the 21st Century: Moving to a Mission-Oriented and Learner-Centered Model, edited by Adrianna Kezar and Daniel Maxey.

Learn more about what students and faculty think of IT by visiting the 2017 Student and Faculty Technology Studies research hub.

Malcolm B. Brown is the director of the EDUCAUSE Learning Initiative at EDUCAUSE.

Jeffrey Pomerantz is a senior researcher at EDUCAUSE.

D. Christopher Brooks is the director of research at EDUCAUSE.

© 2017 Malcolm B. Brown, Jeffrey Pomerantz, and D. Christopher Brooks. This EDUCAUSE Review blog is licensed under Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0.