A survey of college and university websites gives an early indication about the ways institutions are addressing generative AI and what it might mean for higher education.

If 2012 was the year of the massive open online course (MOOC), these first three months are positioning 2023 to be the year of generative artificial intelligence (AI).Footnote1 A recent EDUCAUSE QuickPoll, for example, noted that "few technologies have garnered attention in the teaching and learning landscape as quickly and as loudly as generative artificial intelligence tools," with ChatGPT, the text-generation technology developed by Open AI that is capable of interacting with users in a chatbot-like manner, receiving much of this attention.Footnote2

Driven by a rapid proliferation of reports about ChatGPT, as well as a lack of reports around the use or prevalence of the tool in higher education settings, we were interested in exploring the degree to which college and university websites mention this particular technology. Institutional websites serve many purposes for many different audiences. They reach students, faculty, staff, and the general public, and they include information on admissions, calendars, research, news, events, and financial aid, as well as teaching and learning activities and practices. Whereas institutional websites can be a rich source of information as independent resources, they also provide a collective function in that they can help us see topics of interest across the higher education landscape. For example, institutional websites were one of the ways individuals identified nationwide campus plans and decisions for closures and pivots with respect to the COVID-19 pandemic, and those websites were also used to estimate and identify the prevalence of proctoring tools in North American higher education settings.Footnote3

In this article, we apply the same data-retrieval and analysis methods we used to estimate the use of proctoring tools mentioned above to determine how widely ChatGPT is mentioned on college and university websites in Canada and the United States. Using these data, we also identify the ways in which ChatGPT is mentioned. We focus on ChatGPT, rather than the family of technologies under the generative AI umbrella, because this tool has recently garnered the lion's share of attention. As a result, mentions of ChatGPT can function as a proxy of thinking about generative AI in general.

Rationale

Little literature is available to indicate how many colleges and universities are engaging with generative AI, such as by providing guidance to students, staff, and faculty about this emerging class of technologies. While conversations and webinars on the topic seem to be abundant, and even as some institutions have provided guidance to faculty and students, large-scale and comparative data as to whether and how institutions are engaging with generative AI are currently unavailable.Footnote4 Anecdotally we are aware of a number of institutions that have established generative AI working groups to develop guidance and recommendations. Awareness of the technology also seems high among faculty and students. The EDUCAUSE QuickPoll mentioned above, for example, paints a clear picture of such awareness. Based on 1,070 responses of individuals in higher education, the poll notes that "almost everybody has heard of generative AI, [that 90%] of managers and C-level leaders indicated that they are discussing generative AI with other leaders at least a little bit, [and that] everybody wants to know more, [with the majority of respondents saying] that the recent spike in attention to generative AI has led to an onslaught of questions and ongoing discussions."Footnote5

Although these findings begin to paint a picture of how the higher education sector in North America has engaged with the arrival of generative AI in public consciousness, it would be helpful to gain an awareness of the degree to which institutions are collectively engaging with it at this point in time. Therefore, in an effort to complement and inform emerging findings, we used search engine results of all university and college websites in the United States and all public institutions in Canada to identify mentions of ChatGPT. By gathering and analyzing this information, we are able to provide a proxy of the prevalence of engagement with ChatGPT in North America.

Methods and Considerations

We used the Google Custom Search Application Programming Interface and a list of 2,155 college and university websites in the United States (n = 1,923) and Canada (n = 232) to determine how commonly they had referenced ChatGPT on their websites (as of February 1, 2023). We also examined the first ten results for each institution to ensure representativeness of the query—in either page titles or summary snippets—to confirm precision. Each site returned between 0 and 7,180 results for the term "ChatGPT" (see table 1), with 593 institutions (27.5%) mentioning ChatGPT at least once. Of those that mentioned it, the average number of references was 98 (SD = 572), revealing that though only a quarter of institutions mention ChatGPT, among those that did, there seems to be considerable interest.

| Rank | Educational Institution | Page Results |

|---|---|---|

|

1 |

Boston University |

7,180 |

|

2 |

University of Mississippi |

7,120 |

|

3 |

Northeastern University |

6,310 |

|

4 |

McGill University |

5,210 |

|

5 |

Harvard University |

3,430 |

|

6 |

University of Richmond |

1,680 |

|

7 |

University of the Fraser Valley |

1,670 |

|

8 |

Columbia University |

1,560 |

|

9 |

University of South Florida |

1,260 |

|

10 |

York University |

1,050 |

We then coded a randomized sample of 100 page results to ensure accuracy and to identify the purpose or content of the page results.

Results and Discussion

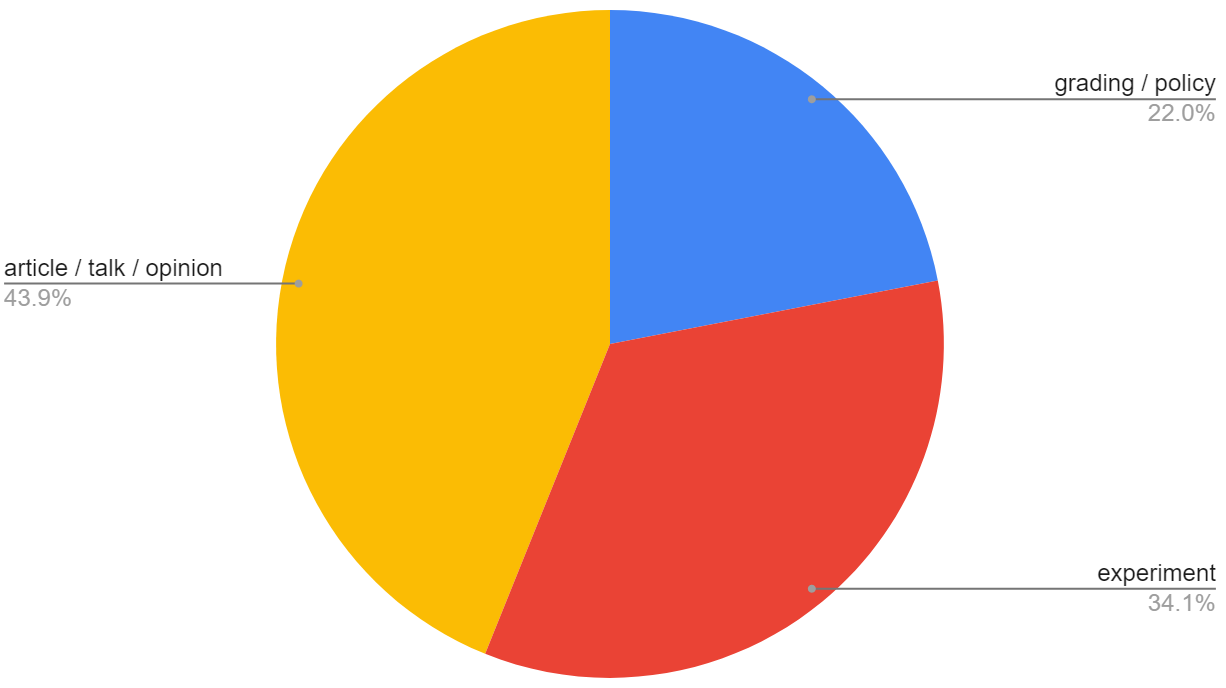

We found that references to ChatGPT on institutional websites included three general types:

- Opinion pieces, articles, or announcements of lectures related to generative AI (e.g., "Ethan Mollick of the Wharton School says that ChatGPT is a tipping point for AI, proof that the technology can be useful…")

- Reports of experiments with generative AI (e.g., "ChatGPT: write the story of the Iran-Contra affair using the language, slang, fashion, and stock characters of a 1980s teen angst comedy…")

- Grading or other policies related to using generative AI in an educational setting (e.g., "Am I allowed to use artificial intelligence [AI] tools such as ChatGPT to generate text or help summarize readings while doing my academic work?")

Thematically, the plurality of references to ChatGPT on institutional websites encompassed opinion pieces or lecture announcements regarding AI (43.9%), followed by experiments with the tools (34.1%), and grading or other academic policies (22.0%) (see figure 1). This may suggest a temporal flow of activity related to adoption in which institutions begin by highlighting opinion pieces on the topic, then provide evidence from faculty experiments with the technology, and then finally adopt policies regarding its use.

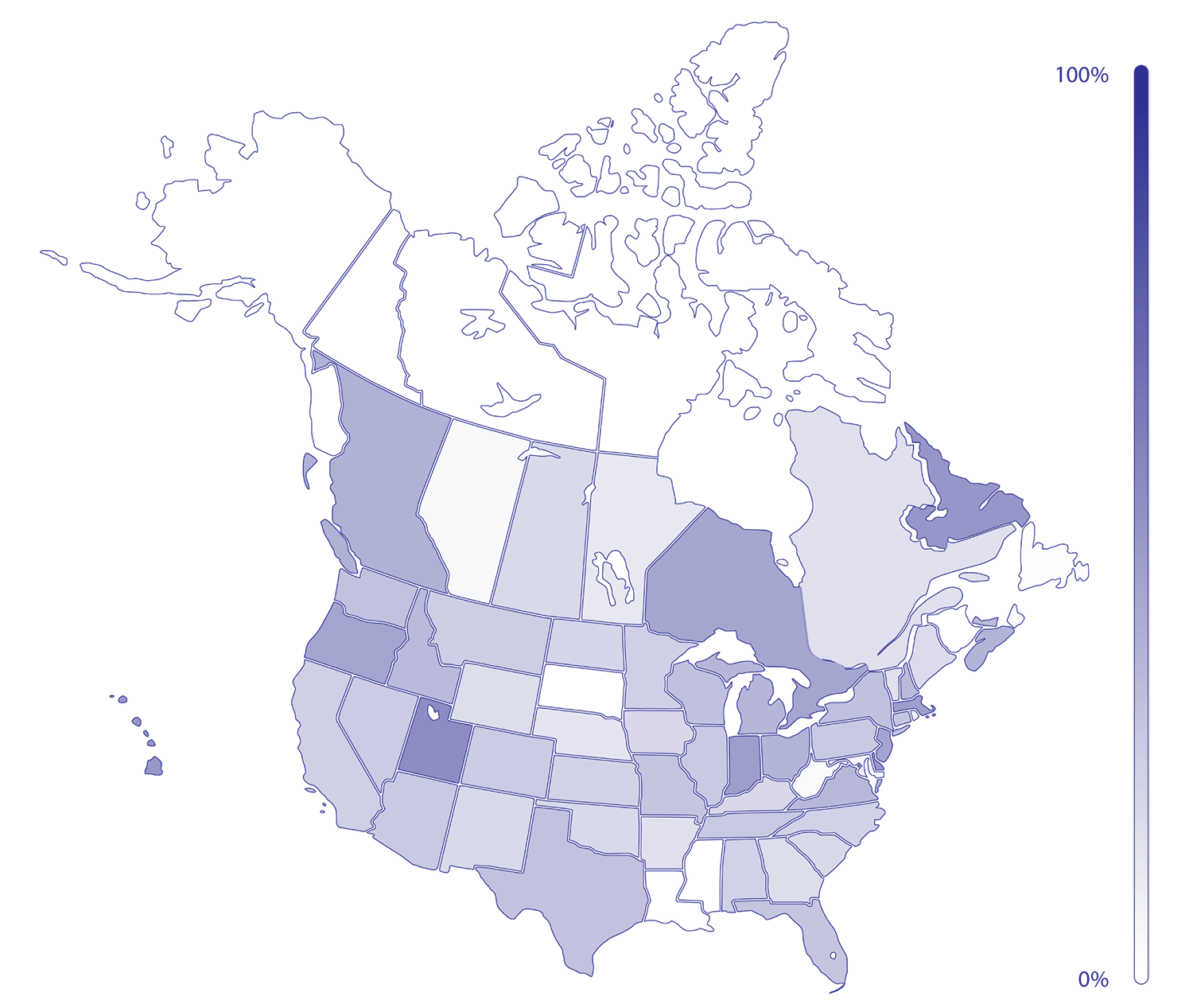

This pattern was not uniform across states and provinces, however. Utah, for instance, was the only state where more than half of its educational institutions mentioned ChatGPT on their websites, but among all of the institutions in the state, the average number of references (21.6) was much lower than in other states such as Mississippi (474.7) and Massachusetts (257.5). The ten states and provinces with the highest number of institutions generally mentioned ChatGPT on roughly one in four websites, with varying averages in result counts (see table 2 and figure 2).

|

State or Province |

Number of Institutions |

Representation |

Results |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Average |

SD |

|||

|

California |

227 |

23.8% |

16.5 |

85.5 |

|

New York |

127 |

30.7% |

25.5 |

161.4 |

|

Texas |

113 |

29.2% |

5.0 |

20.3 |

|

Pennsylvania |

108 |

26.9% |

13.5 |

67.2 |

|

Québec |

90 |

15.6% |

70.1 |

550.1 |

|

Illinois |

84 |

26.2% |

7.8 |

47.6 |

|

Massachusetts |

68 |

47.1% |

257.5 |

1,204.7 |

|

Florida |

67 |

28.4% |

25.4 |

154.3 |

|

North Carolina |

66 |

22.7% |

11.6 |

57.5 |

|

Ohio |

65 |

36.9% |

4.2 |

15.8 |

| Note: This listing includes the ten states/provinces with the highest number of institutions. | ||||

Although some institutional websites included experiments with ChatGPT, what was missing were examples of activities and assessments that make use of ChatGPT. In 1987, Seymour Papert wrote, "Do not ask what LOGO can do to people, but what people can do with LOGO," urging researchers and practitioners to avoid technocentric thinking and to investigate the ways in which LOGO (a programming language) could be used in practice.Footnote6 Institutions of higher education have a unique role to play here, as they are able to host, distribute, and showcase instructional practices that make use of ChatGPT and other AI tools. For example, similar to how the University of Queensland hosts a searchable database of assessments enabling faculty to explore a variety of assessment practices, institutions could highlight ways in which their staff and faculty have conceptualized the use of AI tools in their classrooms.Footnote7 Note that we aren't suggesting wholesale adoption here but rather a sharing of practices across disciplines and traditions, ranging from use of the tool to critiques of the tool and anything in between.

Higher education is often described as slow moving and slow to adapt, but the mass transition to remote learning during the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as the speed with which some institutional websites reflect engagement with ChatGPT in these findings, may suggest that institutional speed with respect to educational technology is relative. There may be instances in which institutions do need to respond quickly, such as in the two examples mentioned above, not necessarily to adopt a technology but to engage with it and seek to understand it and its implications. There may also be times that institutions need to move slowly and with caution—those of us who have been in the field for a while have seen the arrival and then the departure of waves upon waves of technologies supposedly poised to transform educational practices, with some having lasting impacts and others shaped to fit institutional practice.Footnote8

This review represents an early look into mentions of ChatGPT and should not be taken to reflect adoption or use. Rather, it reveals an early measure of engagement with ChatGPT and can provide a context for understanding the degree to which the higher education sector is exploring such tools. These results can provide guidance to institutions as to whether and how their peer institutions are engaging with the technology. Writing about the adoption of proctoring tools in 2021, we noted that "the higher education community needs to responsibly grapple with the implications of this use, reflect on how these shifts respond to actual needs, evaluate the costs of these shifts (in terms of money, privacy, and distrust toward students), and consider whether adopting such tools so quickly and broadly is the best solution to the problems we are trying to solve."Footnote9 We now make the same suggestion about AI.

Notes

- Laura Pappano, "The Year of the MOOC," New York Times, November 14, 2012. Jump back to footnote 1 in the text.

- Nicole Muscanell and Jenay Robert, "EDUCAUSE QuickPoll Results: Did ChatGPT Write This Report?" EDUCAUSE Review, February 14, 2023. Jump back to footnote 2 in the text.

- Bryan Alexander, "How Will Colleges and Universities Plan for January? A Crowdsourced Tracking Project," BryanAlexander.org, December 20, 2021, and Royce Kimmons and George Veletsianos, "Proctoring Software in Higher Ed: Prevalence and Patterns," EDUCAUSE Review, February 23, 2021. Jump back to footnote 3 in the text.

- "Faculty Assembly Talks ChatGPT," CU Boulder Today, February 3, 2023; "Artificial Intelligence and Higher Education: Where Are We Going and How Are We Getting There?" WCET webcast, February 15, 2023; and Julian Hartman-Sigall, "University Declines to Ban ChatGPT, Releases Faculty Guidance for Its Usage," Daily Princetonian, January 25, 2023. Jump back to footnote 4 in the text.

- Muscanell and Robert, "EDUCAUSE QuickPoll Results: Did ChatGPT Write This Report?" Jump back to footnote 5 in the text.

- Seymour Papert, "Computer Criticism vs. Technocentric Thinking," Educational Researcher 16, no. 1 (January 1987): 22–30. Jump back to footnote 6 in the text.

- "Find an Assessment," University of Queensland. Jump back to footnote 7 in the text.

- Martin Weller, 25 Years of Ed Tech (Athabasca, AB: AU Press, 2020). Jump back to footnote 8 in the text.

- Kimmons and Veletsianos, "Proctoring Software in Higher Ed: Prevalence and Patterns." Jump back to footnote 9 in the text.

George Veletsianos is Professor and Canada Research Chair in Innovative Learning and Technology at Royal Roads University.

Royce Kimmons is an Associate Professor of Instructional Psychology and Technology at Brigham Young University.

Fanny Eliza Bondah is a Graduate Student in Instructional Psychology and Technology at Brigham Young University.

© 2023 George Veletsianos, Royce Kimmons, and Fanny Eliza Bondah. The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY 4.0 International License.