Systems thinking and change strategies can be used to improve the overall functioning of a system. Because instructional designers typically use systems thinking to facilitate behavioral changes and improve institutional performance, they are uniquely positioned to be change agents at higher education institutions.

Systems thinking is a way of understanding and analyzing relationships and interdependencies within a system.Footnote1 It is ideal for managing organizational change because it requires each component of the larger picture to be examined individually. Systems thinking and change strategies can be used to improve the overall functioning of a system. In higher education, instructional designers are often seen as "change agents" because they help to facilitate behavioral changes and improve performance at their institutions. Due to their unique position of influence among higher education leaders and faculty and their use of systems thinking, instructional designers can help bridge institutional priorities and the specific needs of various stakeholders. COVID-19 and the switch to emergency remote teaching raised awareness of the critical services instructional designers provide, including preparing faculty to teach—and students to learn—in well-designed learning environments.Footnote2 Today, higher education institutions increasingly rely on the experience and expertise of instructional designers.

Instructional designers work closely with faculty, administrators, students, and other stakeholders to create effective learning solutions that meet targeted educational needs. Their roles may vary depending on their expertise and the needs of the university or college.Footnote3 Regardless of their specific position, these professionals can play a key role in driving change and improvement by helping design and deliver learning experiences that address the needs of the institution and its faculty, staff, and students.

Instructional Designers as Change Agents

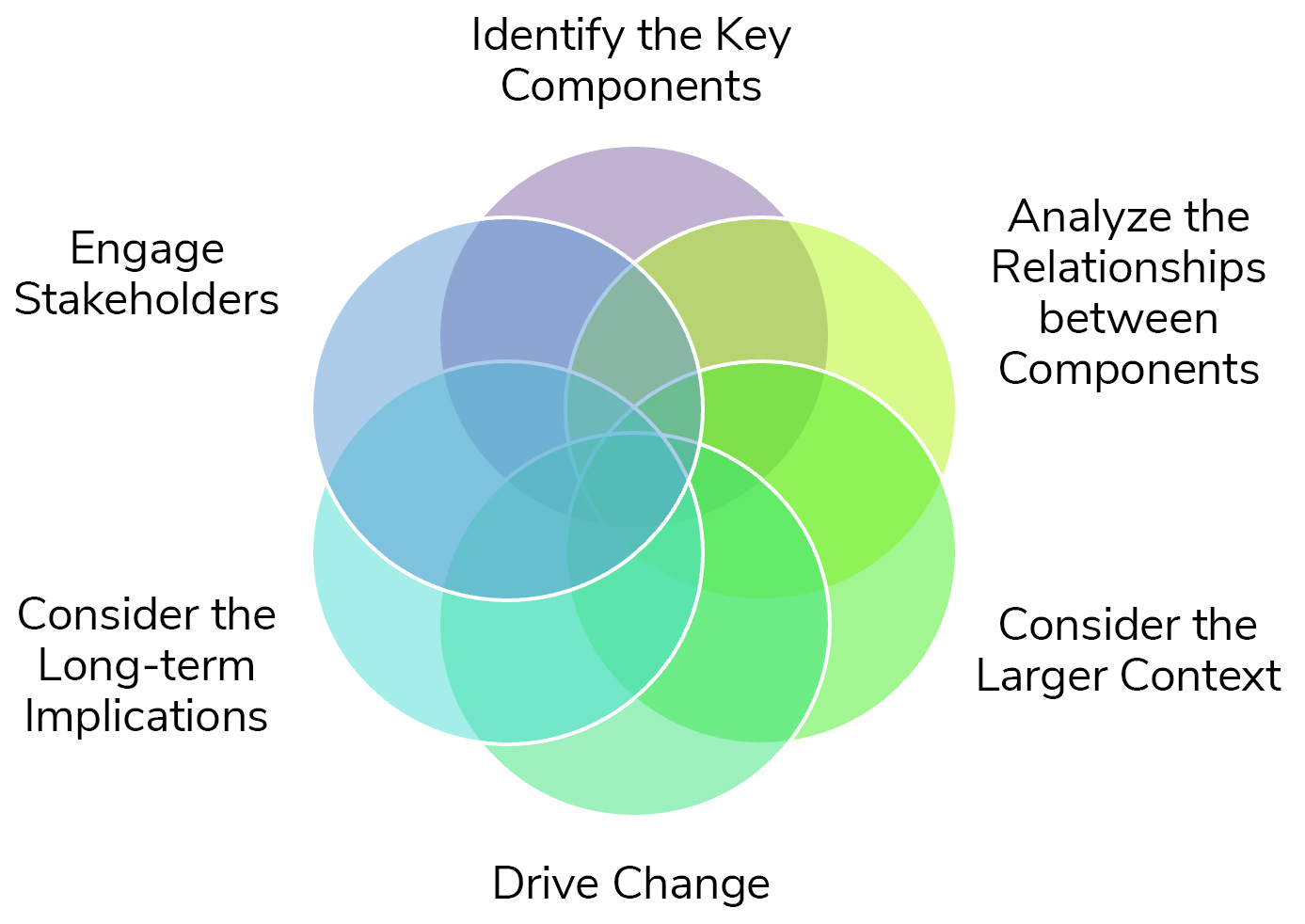

There are many ways in which instructional designers can be positioned as change agents within a higher education institution. They can work collaboratively with stakeholders to identify areas where changes to learning and development initiatives could have a positive impact. This work might involve conducting needs assessments, gathering data, and analyzing results to identify improvement opportunities. They can also help implement and sustain the identified changes. Instructional designers can work with deans, department heads, faculty, and other institutional stakeholders to ensure that new learning materials and approaches are being used effectively. They can vet new technologies, share innovative strategies for implementing instructional changes, and foster conversations with stakeholders about how to systematically facilitate change. Instructional designers can also ensure the necessary support is in place to help all stakeholders successfully adopt new behaviors and practices. Figure 1 illustrates how instructional designers use systems thinking to drive change at their institutions.

Identify the Key Components

Instructional designers can use systems thinking to identify the key components of the system that leaders are trying to change, including the people, processes, and technologies involved. This approach clarifies how the different parts of the system work together and how those parts might impact the system's overall performance.Footnote4 For example, when moving an academic program from an in-person format to an online format, instructional designers can help stakeholders identify the key features of the learning ecosystem. An online learning system includes several curricular components, such as individual courses, course content, and degree requirements; stakeholders and their characteristics, such as faculty readiness and student engagement; administrative processes, such as admissions, enrollment, and program assessment; and technological components, such as learning management systems and communication tools. Identifying the elements of the system is the first step in understanding the broader learning context and how such components interact dynamically to facilitate change.

Analyze the Relationships between Components

Once the key components of the system are identified, systems thinking can be employed to analyze the relationships between these features. This analysis clarifies how changes to one part of the system might impact others and informs how stakeholders adapt to or implement change. Instructional designers work across the institution to help create cohesive programs. They explore how components of the curriculum—including core courses, electives, and experiential learning opportunities—interact and influence the overall effectiveness of the program. By mapping these relationships, an instructional designer might propose changes that encourage cross-disciplinary collaboration and meaningful connections between courses and identify extracurricular learning opportunities. Such a systematic curriculum review improves overall decision-making. The instructional designer might suggest creating interdisciplinary project-based courses in which students from different disciplines collaborate on real-world projects. This approach fosters a more cohesive learning experience—allowing students to see the interconnectedness of the subjects they're studying—and promotes a deeper understanding of complex topics. Regardless of the final solution, when contemplating significant changes, such as developing new or revised academic offerings, analyzing the entire curriculum benefits all stakeholders.

Consider the Larger Context

Systems thinking also involves considering the larger context in which the system operates. This exploration might include external factors, such as the economy, technology, or societal trends, or internal factors, such as institutional culture, values, and goals.Footnote5 Considering the larger context helps instructional designers to better understand the opportunities and challenges faced by the system and how to address them so they can help stakeholders see the larger picture.

For example, an instructional designer might be asked to help an institution implement a competency-based education program. By considering external factors (e.g., industry demands) and internal factors (e.g., curriculum alignment with specific skills and knowledge), instructional designers can provide guidance to ensure that the program aligns with the larger context and the mission of the college or university. To better understand the external landscape, instructional designers might examine the evolving higher education landscape and workforce demands. By researching industry trends, job market requirements, and emerging technologies, instructional designers can help stakeholders understand the skills and competencies that students need to succeed in the modern workforce. To better understand the internal context, instructional designers might collaborate with faculty members, department heads, and administrators to assess the culture, values, and goals of the institution. They might conduct interviews, surveys, and focus groups to understand faculty readiness to adopt a competency-based approach, student expectations, and the broader educational mission of the institution. Instructional designers can use what they learn from these explorations to provide a comprehensive description of the larger picture, helping the institution address difficult decisions and facilitate change efforts.

Drive Change

Systems thinking can be employed to design feedback loops that help drive change within the system. Feedback loops involve gathering data on the performance of the system, analyzing the data to identify areas for improvement, and taking action based on the analysis. Using feedback loops to continuously gather and analyze data allows instructional designers to drive ongoing change and improvement within the system. For example, when designing a campus professional development program, an instructional design team can ensure that feedback loops are built into each step of the program. Instructional designers might look at aggregated student scores, technology usage, or end-of-course surveys to identify areas for course improvement and faculty training. Conducting a faculty needs assessment to determine gaps can help instructional designers create meaningful learning experiences that promote improvements in faculty performance. Gaining perspectives from program leaders, deans, and department heads can ensure that the professional development curriculum aligns with institutional priorities. Finally, following each professional development session or activity, participants should be given the opportunity to provide insight into their learning experiences. Providing multiple opportunities for feedback contributes to the change process and helps grow a culture of continuous improvement. Such cultures foster robust systems and organizations.Footnote6

Consider the Long-term Implications

Systems thinking encourages a long-term perspective, which can be valuable when considering the possible consequences of change in various environments. Instructional designers can use this perspective to anticipate and plan for the potential impacts of changes on the larger system, including the long-term effects on learning and student success. When instructional designers are included in decisions about instructional technology adoption, they can help institutions consider the long-term implications by providing insights into evolving student needs and technology advancements. For example, as institutions grapple with the rapidly developing implications of generative artificial intelligence (AI), instructional designers can help institutional stakeholders better understand how such technologies might impact the educational system in the future. Recognizing that technology trends affect learning experiences and academic integrity, instructional designers can ensure that selected learning platforms are scalable and compatible with emerging technologies. By considering the longevity of a tool or product and its potential impact on the larger learning system, instructional designers can help faculty and academic programs remain relevant and effective over time. Including an instructional designer with a systems thinking perspective in the instructional technology decision-making and adoption process results in educational offerings that provide students with the skills and knowledge they need to be successful in today's workforce.

Engage Stakeholders

Systems thinking emphasizes the importance of engaging all stakeholders in the change process. Instructional designers who use this approach involve a wide range of stakeholders—including learners, educators, administrators, instructional and technical support personnel, and other key players—in designing and implementing learning interventions. Building relationships with stakeholders helps facilitate meaningful change. Instructional designers can provide valuable expertise and support and build consensus among stakeholders when institutions explore implementing a policy change or creating a new policy that involves instructional technologies or innovative pedagogical strategies. For example, instructional designers may be actively engaged in campus conversations about policy development to support the use of generative AI in teaching and learning. Since instructional designers tend to be familiar with the larger educational ecosystem, they can identify stakeholders who would have relevant insights or would be impacted by such policies and find ways to engage them in conversations to ensure all perspectives are represented. Instructional designers are well-positioned to take on the following tasks:

- Help leaders understand the benefits and potential downfalls of using generative AI to inform decision-making about institutional policies

- Assist faculty with course design plans that include AI in assignments while helping to craft policy statements to mitigate cheating

- Organize and facilitate learning communities to openly discuss the implications of policies regulating AI across different disciplines and organizational units

- Hold focus groups with students to better understand how they might use AI in their pursuit of knowledge

- Engage with external stakeholder communities to gain insights about the AI-related skills graduating students should have

The complexities involved in creating or revising policies are difficult to navigate. Instructional designers who take a systems thinking approach and employ inclusive stakeholder engagement strategies are ideally suited to contribute to these initiatives.

Communicating and Elevating the Role of the Instructional Designer

Instructional designers can play critical roles as change agents, but institutional leaders must recognize and leverage the unique function these professionals have at their institutions. Learning is a catalyst for impactful change. Instructional designers can help campus leaders and stakeholders understand how learning opportunities drive change in higher education by sharing research and data on the impact of tools, pedagogical strategies, best practices for student performance, or examples of successful learning initiatives within or at other higher education institutions.

Instructional designers can also demonstrate value by using their individual expertise to further institutional goals. The design and development of learning opportunities require instructional designers to share their knowledge and experience with higher education leaders and stakeholders. They might present on topics related to learning and change or provide guidance and support to help stakeholders understand the process of designing and delivering effective learning experiences.

Instructional designers should work closely with leaders and stakeholders to understand their needs and design learning solutions that address them. Open dialogue, transparent interactions, and active collaboration can build trust and credibility and help stakeholders understand the value instructional designers bring to the institution.Footnote7

Finally, using data to inform decisions and report on progress can be helpful when demonstrating the value of instructional design. Instructional designers can provide institutional leaders and stakeholders with a better understanding of the impact of learning by measuring and reporting on the results of learning initiatives. They might track performance metrics, gather feedback from learners and stakeholders, and share success stories and case studies.

Final Thoughts

Throughout the design process, instructional designers often employ systems thinking approaches to influence instructional quality and effectiveness. Instructional design work involves identifying individual components of a program or course and recognizing how those components work together in an educational system. Instructional designers are uniquely positioned within higher education, balancing theory and practice. To remain current, instructional designers must constantly research new tools and strategies and provide guidance on using them effectively in the educational system. Instructional designers understand how to collect and use data to improve the overall system. They often form partnerships with faculty and administrations and can play a key role in bringing change to their institutions. Leaders should recognize the unique role of instructional designers and leverage their distinctive expertise to influence and lead change efforts in higher education.

Notes

- Derek Cabrera and Laura Cabrera, Cabrera Research Lab (website), accessed September 6, 2023. Jump back to footnote 1 in the text.

- Monica W. Tracey and Elizabeth Boling, "Preparing Instructional Designers: Traditional and Emerging Perspectives," in Handbook of Research on Educational Communications and Technology, eds. J. Michael Spector, M. David Merrill, Jan Elen, and M. J. Bishop (New York: Springer, 2014), 656; To read case studies involving systems thinking in a variety of contexts, see M. Aaron Bond et al., eds., Systems Thinking for Instructional Designers: Catalyzing Organizational Change (New York: Routledge, 2021); Charles Hodges et al., "The Difference Between Emergency Remote Teaching and Online Learning," EDUCAUSE Review, March 27, 2020. Jump back to footnote 2 in the text.

- For a comprehensive look at the roles instructional designers play in higher education, see Rhiannon Pollard and Swapna Kumar, "Instructional Designers in Higher Education: Roles, Challenges, and Supports," The Journal of Applied Instructional Design 11, no. 1 (2022). Jump back to footnote 3 in the text.

- For a more detailed explanation of how instructional designers use systems thinking in higher education, see Barbara Lockee et al., "Beyond Design: The Systemic Nature of Distance Delivery Mode Selection," Distance Education 43, no. 2 (April 2022): 204–220. Jump back to footnote 4 in the text.

- Katy Campbell and Richard A. Schwier, "Major Movements in Instructional Design," in Online Distance Education: Towards a Research Agenda, eds. Olaf Zawacki-Richter and Terry Anderson (Athabasca: Athabasca University Press, 2014), 345–380. Jump back to footnote 5 in the text.

- For a more detailed discussion about learning organizations, see Peter Senge, The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization (New York: Crown Business, 2006). Jump back to footnote 6 in the text.

- For more discussion of instructional designers as change agents in higher education, see Justin A. Sentz, "The Balancing Act: Interpersonal Aspects of Instructional Designers as Change Agents in Higher Education," in Cases on Learning Design and Human Performance Technology, (Hershey, PA: IGI Global, 2020), 58–79. Jump back to footnote 7 in the text.

M. Aaron Bond is Senior Director, Learning Services for Technology Enhanced Learning and Online Strategies at Virginia Tech.

Barbara B. Lockee is Associate Vice Provost, Faculty Affairs, and Professor, Instructional Design and Technology at Virginia Tech.

Samantha J. Blevins is Instructional Designer and Learning Architect at Radford University.

© 2023 M. Aaron Bond, Barbara Lockee, and Samantha J. Blevins. The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 International License.