The INCLUSIVE ADDIE model was created to extend the popularity of the ADDIE model and support diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) in instructional design and course implementation.

All individuals in learning communities across higher education should feel welcome and have a sense of belonging regardless of their race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, religious affiliation, or physical, psychological, intellectual, and linguistic abilities. The broad definition of inclusion that follows captures our perspective as instructional designers and researchers. It was developed from a literature review and extensive discussions with professionals and instructional designers on the importance of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) in course design.

Studies show that noninclusive behaviors in learning environments include, but are not limited to, stereotype threat in interactions.Footnote1 For example, course materials may include works that are written or produced by scientists from dominant groups and leave out resources by scientists from underrepresented groups.Footnote2 Unconscious bias also contributes to a noninclusive learning environment. Instructors and learners have different identities, and most of the time, individuals do not recognize how their identities shape the way they interact with others or the way others interact with them.Footnote3 And while colleges and universities have policies and guidelines in place to support students with physical disabilities, institutions also need to support learners with varying psychological, intellectual, and linguistic abilities.

Learning environments should foster a sense of belonging and make all students feel welcome, valued, and respected. The instructional design process should avoid negative stereotypes and unconscious bias, encourage respect, representation, access, and communication, and recognize students with varying abilities. To achieve these goals, a more comprehensive, inclusive instructional design model is needed. We propose the INCLUSIVE ADDIE model.

The INCLUSIVE ADDIE Model

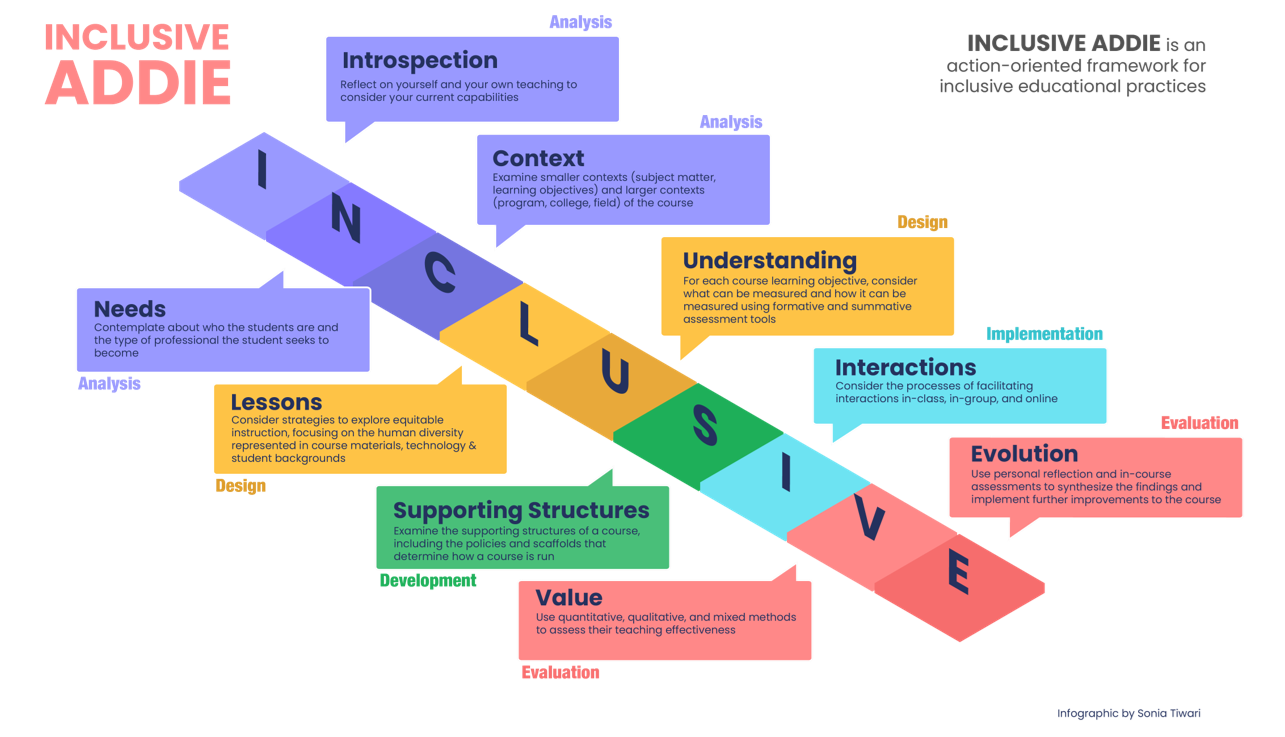

Our new INCLUSIVE ADDIE model is an extension of previous work on inclusive teaching and course design.Footnote4 It is based on the ADDIE model, a well-known instructional design framework that includes the following five stages: analyze, design, develop, implement, and evaluate.Footnote5 In response to critiques that the ADDIE model misses a crucial cultural component,Footnote6 the INCLUSIVE ADDIE model adds nine substages that infuse inclusive practices into the pedagogical process: introspection, needs, context, lesson, understanding, supporting structures, implementation, values, and evolution (see figure 1).

Our understanding of inclusive pedagogy was informed by expanding (1) the context of inclusion to encompass sociocultural factors and physical abilities; (2) the application of the model to include multiple stakeholders (students, faculty, and instructional designers); and (3) the model from conceptual to concrete, with actionable steps for the systematic realization of inclusive teaching and learning in higher education. Figure 1 and table 1 provide an overview of the model. In addition, we have created a supplemental workbook that offers prompts and spaces for faculty and instructional designers to reflect and sketch their ideas on how to improve their course design.

| Analysis: Define the problem, identify the source of the problem, and determine possible solutions. |

|---|

|

Introspection: Reflect on yourself and your teaching to consider your current capabilities. |

|

Needs: Contemplate who the students are and the type of professionals they seek to become. |

|

Context: Examine smaller contexts (subject matter, earning objectives) and larger contexts (climate of the program, college, and IS field). |

| Design: Plan a strategy for developing the instruction. |

|

Lessons: Consider strategies to explore equitable instruction, particularly focusing on the human diversity represented in course materials, technology disparities, and diverse student backgrounds. |

|

Understanding: For each course learning objective, consider what can be measured and how formative and summative assessment tools can be used to measure those objectives. |

| Development: Generate the lesson plans and lesson materials. |

|

Supporting Structures: Examine the supporting structures of a course, including the policies and scaffolds that determine how a course is run. |

| Implementation: Deliver effective and efficient instruction. |

|

Interactions: Consider the processes for facilitating in-class, in-group, and online interactions. |

| Evaluation: Measure the effectiveness and efficiency of the instruction. |

|

Values: Use quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods to assess teaching effectiveness. |

|

Evolution: Use personal reflection and in-course assessments to synthesize the findings and implement further improvements to the course. |

Analysis

During the analysis stage, the course inputs should be examined by the development team (instructional designers and faculty). The instructor, students, placement of the course within the academic program, and the positioning of the course content within its field of study should also be reviewed. Considering each of these inputs helps to determine how to make the most of what is available.

Introspection

During the introspection step, reflect on your identities and consider the privileges and social support associated with them. Identities can be grouped into two major categories: professional and personal. A professional identity describes how you see yourself in your role in the workplace, and a personal identity describes who you are as a person beyond the workplace. In many cases, these two identities will overlap, and both play a role in shaping your decisions for the course.

Helen Neville and her colleagues designed a survey for guided introspection, with prompts around key aspects of inclusion. For example, to help faculty to think about their beliefs toward multiculturality, Neville and her colleagues designed multiple-choice questions that include response options like these: (a) "I believe in treating every student equally as a person who has an equal opportunity to be outstanding in science," and (b) "I believe that in an inclusive classroom educators should focus on what makes students the same and not focus on what makes students different (e.g., race and gender)."Footnote7

After reflecting on your identities, consider your influences—both what influences you and where you exert influence. Cultural influences (worldview) are things that influence you. Such influences can be informed by your education, religion, geography, and socioeconomic status and span experiences from your youth to your current day-to-day life.

An educator's role is traditionally one of authority. The cultures you influence (power dynamics) are informed by your formal and informal social and organizational positions. When describing the cultures you believe you have impacted, consider how you approach these environments. How much influence and power do you have in these areas, and how might that change over time?

Think about how your teaching philosophy influences student interactions. Input from your personal and professional life can help you improve your understanding of and empathy for diversity and inclusive practices, as well as your ability to work with others. Deep introspection will allow you to evaluate students' current capabilities and may help to influence the decisions you make throughout the course. Assessing your privileges and social support network help you understand how those things impact you. Reflecting on your teaching philosophy presents an opportunity for you to inspect the decisions you make during the course design and material preparation stages so that you can create an equitable environment for all students.Footnote8

Needs

Understanding students' needs can be split into two parts: understanding a student's identities and understanding the type of professional the student is looking to become in the workplace. It can be easy to make generalizations about undergraduate students (or students of any kind). However, each student has many unique attributes. To begin understanding students' identities, review the student body metrics within your department (admissions and graduation statistics are good starting points). What do these metrics reveal about your department's gender, race, and ethnicity composition? Michail Giannakos and his colleagues gathered information about students' needs with questions about the degree's usefulness and potential barriers that could influence students' decision to leave their studies.Footnote9 Surveys like these could be used at the beginning of the semester to understand students' needs, inform the implementation of any potentially helpful ideas as the academic year unfolds, and, ultimately, support retention.

Provide an open and welcoming space for students to express their identities in class. Analyzing and understanding the student population at the course, program, and academic college levels can help you improve communication. Students may volunteer information about themselves that will help you connect with them as people, which, in turn, will allow for more meaningful connections to learning.

Students may have many goals and reasons for taking a course. Think about the possible workplaces, professional fields, or industries students could enter after going through the classes you teach or support. Considering the needs of students and their desired professional trajectories can be challenging, requiring you to balance the goals of helping students grow their expertise in a field and meet the specific course objectives.

Consider the workplace cultures students might encounter during their careers. After reflecting on the fields in which your students are likely to work, think about the demographics and culture of those workplaces. How different or similar are they from the student body metrics you identified above? As students begin to develop their professional identities and progress from being novices to experts, they may feel like they are outsiders in their chosen fields and be afraid that they don't belong. Reflecting on students' professional goals can give you the necessary perspective to help them overcome this fear. When students are given opportunities to demonstrate their skills and passion for their work, they are more likely to succeed in their classes and envision themselves as becoming capable, contributing members of their chosen professions (not as outsiders who are excluded for circumstances beyond their control; e.g., skin color or sexual orientation). Moreover, when you have a better sense of your students' intended professional goals, you can leverage that knowledge in your classes by including examples and jargon that aligns with the fields that students are likely to enter.

Finally, having a better understanding of students' needs allows you to provide them with contextual advice. First, consider your own experiences and knowledge. What advice could you provide to your students based on your own experiences? You can also leverage other people's expertise to support your students. These resources can often provide more diverse perspectives, which can be useful if you can't relate to the situations your students are experiencing. Identifying how you can support the needs of your students in these varying ways will help you create corresponding scaffolds in the course.

Context

When thinking about the context of the course, first explore its nature—the subject matter, learning objectives, and academic rigor. Understanding the nature of the course makes it easier for you to explain and easier for your students to understand.

Second, reflect on progressively larger contexts for the course, such as the climate of the program, institution, and field of study. In their article about how black students in computer science classes struggle with the anti-black stereotypes that persist in education, Stephanie Jones and Natalie Melo argued that context of the course cannot be seen in isolation from the larger context; the context of the course serves as the basis of any inclusive teaching practice.Footnote10 An examination of larger contexts can help you understand the course and its relevance, as well as how it is perceived and valued by others in your field and how it connects to modern professional practices. Reflections like these will help you identify what elements from your course might inform students' learning in other classes and what concepts you would like students to remember about the course five to ten years later.

After understanding the larger context of the field, identify what institutional resources are available to help students, faculty, and staff feel welcome and supported. These resources might include an accessibility accommodations office or student clubs and organizations where peers can support each other. There are also resources available through colleges and universities that can be leveraged to enhance your knowledge and skills in teaching and learning with diverse student groups. Reflect on how some of these resources might be useful in your future teaching.

Think about the types of jobs your students are likely to get by examining the current and future state of the industries they are likely to enter. Look at the current demographic composition and the predicted trends for the next five to ten years, as these benchmarks can help you understand current and future opportunities and challenges for these ambitious professionals. Emerging trends and points of contention within various fields can be further explored and explained within the course to help students prepare for their future roles. This information might be available through a college or university careers office.

Awareness of the geopolitical contexts is also important, especially given the constantly evolving policies and relationships between countries. Changing policies related to international students, faculty who are visiting from other countries or are currently out of the country, and students in study abroad programs can influence in-class collaborations. Ask yourself how this additional layer of complexity and potential source of stress might impact people's lives and what can be done to lessen this burden? What structures can be built into the course to accommodate potential impacts on students and faculty?

Design

Design refers to the strategy of the course and includes the curation of course content materials and mechanisms for assessing if learning objectives have been met.

Lessons

When creating lessons for a course, explore strategies that can make instruction more equitable (focus particularly on diverse course materials and content that is suitable for students from a variety of backgrounds). Diverse course materials could include, but are not limited to, readings, videos, and technology. When selecting course materials, consider whether the content represents differing perspectives. Reflect on who is being presented as an authority in the materials. Your selection of course materials brings with it a tacit statement about the authors and other individuals you consider worthy of including. Students benefit from seeing a relatable part of themselves in the materials. In her book chapter about proportions in interacting social groups, Rosabeth Moss Kanter explains that in order for an organization to be considered diverse, a minimum of 33 percent of its employees should be from underrepresented groups.Footnote11 Consider this minimum benchmark for diversity in the materials for your courses as well.

Technology can present various challenges for students, particularly those who are unable to access it due to geographic availability, financial constraints, or short- or long-term impairments. When investigating hardware and software technologies to use in a course, consider accessibility and cost. What technology and other materials are required for your class, and what are the potential barriers to accessing these materials? If there are institutional resources to help lessen these barriers, how might those resources be utilized in your course? Depending on the size of a course and other factors, training and technical support resources may need to be robust to allow for troubleshooting and certain use accommodations.Footnote12

Not all students have the same educational background, so there will inevitably be differences in what students know on the first day of class. Consider offering additional resources (when available and relevant) such as a refresher on the course prerequisites, writing or test-taking strategies, and tutoring. When drafting your course outline, consider the educational background of your students. What should your students already know? What are the prerequisites for the course? Are there mechanisms for remediation to help students catch up if needed? You might identify available resources at the beginning of the course, or wait until the course is underway to determine whether additional support materials are needed. In contrast, some students may come to class with a great deal of knowledge about or experience in the course topic. Consider presenting challenges to keep these students engaged with and excited about the course content.

Understanding

Taking a multimodal approach to assessment allows you to analyze the effectiveness of the course content through multiple lenses and triangulate what students know and what they can do.Footnote13 For each course learning objective, consider what can be measured and how. Multiple types of assessment and assessment adjustments can also benefit students. Different assignment types (e.g., essays, projects, and presentations) require students to utilize and develop different skill sets rather than rely on a single ability. Variation also supports students, as they may have difficulties with certain types of assignments. For example, students with high anxiety may struggle with high-stakes exams or public speaking. While this approach is valuable, you should also acknowledge the constraints presented by different types and sizes of courses and consider the tradeoffs of each assignment and its role as a formative or summative assessment.

For each assignment type, consider the frequency of feedback. Feedback provides opportunities for students to develop, grow, and adjust throughout the course. Regular feedback prevents students from progressing with misconceptions and encourages further reflection. Think about whether you provide regular feedback to your students or have built other feedback mechanisms into your course. If you cannot give feedback directly, can students get feedback from their classmates through peer review or discussions? Also, consider how feedback is provided. Students need to be able to read and understand the feedback for it to be effective. Review and evaluate rubrics and other feedback mechanisms for assumptions about students' knowledge and experience with the cultural norms. Utilize students and teaching assistants to help incorporate the student perspective.

Development

Development involves building the course in the platform where it will run and establishing procedures that govern how the course will run, including elements (unrelated to content) that are designed to help students succeed.

Supporting Structures

The supporting structures of a course include the policies and other details that determine how the class will run. Start by looking at existing institutional policies.Footnote14 For example, colleges and universities have policy statements covering discrimination and harassment, disability accommodations, and military accommodations. You may also decide to include language that outlines acceptable behavior in your class. Other discretionary policies could be added for late assignments, missing classes, make-up work, etc. For example, many policies were added to courses due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Discretionary policies are typically shaped by the instructor's experience, tolerance for acceptable behavior and exceptions, and availability (e.g., time).

Scaffolds within the course provide navigational structure to students. They come in many forms (e.g., reminders, calendars, and detailed outlines of course expectations) and are added to the course to support students' performance. Clear explanations can help students focus their energies on what they need to accomplish. For example, students with learning disabilities or those with limited experience in a higher education setting may find it daunting to even know where to start in a course. The challenges in a class should come from content and assignments that help students build their knowledge and develop their skills. Students should not have to struggle to figure out when an assignment is due. Think about the difficulties students have expressed regarding your course from previous semesters and consider how current or new scaffolds address those difficulties.

Implementation

Implementation puts the design into practice (running the course) and includes strategies for responding to students' needs.

Interactions

Processes for facilitating in-class, in-group, and online interactions should all be considered in this step. Running the course allows you to implement and test policies that you designed. Setting up and articulating the policies upfront ensures that accommodations are applied consistently, providing greater equity for all students. Create opportunities for students to share their ideas at different stages of their studies.Footnote15 Some examples include new-student orientation, where students can express their concerns with starting something new, online tracking systems with built-in conversation opportunities to identify trends in students' needs, lab spaces for formal and informal interactions to develop students' interests and promote further exploration, exams based on summary notes demonstrating how students are organizing their knowledge and study practices, and peer tutoring to capture and share the student experience in challenging course content.

As you implement course interaction processes, think about the distinction between equality and equity. For example, when is it appropriate to apply a one-size-fits-all policy, and when is it not? In-class policies can create a standard for interactions and support a collegial environment. However, special circumstances may arise. When possible, leverage the expertise and experience of others to help you make decisions. Collaborative work is a beneficial part of many classroom experiences, as it generates opportunities for healthy student interactions. Consider how groups are formed and how group dynamics are supported. Some students may feel isolated, dominated, or like they are not contributing during group work. When implementing group projects, consider how to ensure groups are functioning well and what to do if there are problems. In addition to group work, students can learn a great deal from constructive criticism provided through peer-review and peer-evaluation activities. By providing specific criteria for these types of assignments, students (including those who otherwise might be unlikely to comment) may be more likely to provide feedback.

Online presence during course interactions involves many of the same risks associated with other online interactions. Students are more likely to interpret another student's comments as rude, dismissive, or insensitive when completing online assignments in a discussion forum, for example. Online interactions can be challenging for students since they lack the benefit of reading the faces and body language of their peers. How can you and your students create a collegial environment? Establish social norms in your syllabus and assignment details and demonstrate those social norms through your own behavior.

Evaluation

During the evaluation stage, reflect on what worked well and what could be improved in future iterations of the course.

Values

Designing or revising a course to promote diversity and inclusion is admirable, but this undertaking can seem fruitless if there is no way to measure it. When implementing changes in a class to encourage something you value, consider how you will measure what you want to change. Measurements can be quantitative, qualitative, or a mixture of both and should help guide the decisions you make in future teaching efforts. Diane Ceo-DiFrancesco and her colleagues suggest that many instructors model their pedagogical practices after the teaching style of their own teachers, and that instead educators should "reexamine [their] assumptions and biases," provide "challenging and demanding content that stretches [their and their students'] understanding of key issues," and foster "interdisciplinary communities of learners in supportive environments."Footnote16 Consider establishing metrics that you want to track (such as students' perception of the course) to evaluate your progress. Create an evaluation plan based on the data types of your choice, as well as the criteria for determining how influential your efforts are.

Evolution

Like many design processes, INCLUSIVE ADDIE encourages iterative course improvement. When measuring improvements in a course, synthesize the findings and implement new or updated tactics to improve the course further. Each term offers an opportunity to improve another part of the course. Finally, the model finishes where it starts: with you! Consider how you might improve personally. Are there lectures, workshops, or other ways to learn more about supporting a diverse student population? Think about what resources are available and what you want or need to know more about. Develop a network of inclusive teaching advocates you can share your experiences with and learn from. Debra Sellheim and Mary Weddle designed a course-reflection process to support the evolution of diversity and inclusion practices. Their approach includes reviewing and reflecting on course objectives, workload, content depth and breadth, and teaching strategies, and integrating practical or clinical experiences in the course.Footnote17 As instructors and instructional designers, you can use similar reflective processes to ensure that your inclusive pedagogical practices evolve over time.

Conclusion

This article offers a series of design considerations intended to support DEI in higher education courses. The suggestions are intended to be broad and useful to a variety of disciplines of study. The INCLUSIVE ADDIE model was created to extend the popularity of the ADDIE model and support faculty and instructional designers as they focus on the needs of an increasingly diverse student body. We encourage other teaching and learning professionals to adopt, test, and improve upon the INCLUSIVE ADDIE model.

Acknowledgment

This article would not be possible without the support of Lynette Yarger, Penn State College of Information Sciences and Technology; Jason Gines, Pembroke Hill School; and funding from Penn State's Equal Opportunity Planning Committee.

Notes

- Thomas P. Sawyer, Jr. and Lisa A. Hollis-Sawyer, "Predicting Stereotype Threat, Test Anxiety, and Cognitive Ability Test Performance: An Examination of Three Models," International Journal of Testing 5, no. 3 (2005): 225–246; Steven J. Spencer, Christine Logel, and Paul G. Davies, "Stereotype Threat," Annual Review of Psychology 67 (2016): 415–437; Tess L. Killpack and Laverne C. Melón. "Toward Inclusive STEM Classrooms: What Personal Role Do Faculty Play?" CBE—Life Sciences Education 15, no. 3 (Fall 2016): 1–9. Jump back to footnote 1 in the text.

- Corinne A. Moss-Racusin, John F. Dovidio, Victoria L. Brescoll, Mark J. Graham, and Jo Handelsman, "Science Faculty's Subtle Gender Biases Favor Male Students," Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109, no. 41 (October 2012): 16474–16479. Jump back to footnote 2 in the text.

- Helen A. Neville, et al., "Color-Blind Racial Ideology: Theory, Training, and Measurement Implications in Psychology," American Psychologist 68, no. 6 (September 2013): 455–466. Jump back to footnote 3 in the text.

- Chris Gamrat, "Inclusive Teaching and Course Design," EDUCAUSE Review, February 2020; Gamrat, Chris. "Fostering Inclusive Practices among Teaching Assistants," EDUCAUSE Review, August 24, 2021; Brian Dewsburry and Cynthia Brame, "Inclusive Teaching," CBE-Life Science Education 18, no.2 (Summer 2019): 1–5. Jump back to footnote 4 in the text.

- As Molenda explains, the origins of the ADDIE model are not entirely clear, so it is difficult to know the original intent and scope of the tool. See Michael Molenda, "In Search of the Elusive ADDIE Model," Performance improvement 42, no. 5 (May 2003): 34–37. Jump back to footnote 5 in the text.

- Michael Thomas, Marlon Mitchell, and Roberto Joseph, "A Cultural Embrace," TechTrends 46, no. 2 (2002): 40–45. Jump back to footnote 6 in the text.

- Neville, et al., "Color-Blind Racial Ideology," 455–466; Dewsburry and Brame, "Inclusive Teaching," 1–5. Jump back to footnote 7 in the text.

- Barbara Seidl and Stephen Hancock, "Acquiring Double Images: White Preservice Teachers Locating Themselves in a Raced World," Harvard Educational Review 81, no. 4 (December 2011): 687–709. Jump back to footnote 8 in the text.

- Michail N. Giannakos, Illias O. Pappas, Letizia Jaccheri, and Demetrios G. Sampson, "Understanding Student Retention in Computer Science Education: The Role of Environment, Gains, Barriers, and Usefulness," Education and Information Technologies 22, no. 55 (September 2017): 2365–2382. Jump back to footnote 9 in the text.

- Stephanie T. Jones and Natalie Melo, "'Anti-Blackness Is No Glitch': The Need for Critical Conversations within Computer Science Education," XRDS: Crossroads, The ACM Magazine for Students 27, no. 2 (Winter 2020): 42–46. Jump back to footnote 10 in the text.

- Rosabeth Moss Kanter, "Some Effects of Proportions on Group Life," in The Gender Gap in Psychotherapy, eds. Patricia Perri Rieker and Elaine Carmen (Boston: Springer, 1984), 53–78. Jump back to footnote 11 in the text.

- Christine Hockings, Paul Brett, and Mat Terentjevs, "Making a Difference—Inclusive Learning and Teaching in Higher Education through Open Educational Resources," Distance Education 33, no. 2 (July 2012): 237–252. Jump back to footnote 12 in the text.

- Robert E. Stake, The Art of Case Study Research (California: Sage, 1995). Jump back to footnote 13 in the text.

- Ian Hardy and Stuart Woodcock, "Inclusive Education Policies: Discourses of Difference, Diversity and Deficit," International Journal of Inclusive Education 19, no. 2 (April 2015): 141–164. Jump back to footnote 14 in the text.

- Keith Nolan, Aidan Mooney, and Susan Bergin, "Facilitating Student Learning in Computer Science: Large Class Sizes and Interventions," in Proceedings of the International Conference on Engaging Pedagogy, Dublin, December 2015. Jump back to footnote 15 in the text.

- Diane Ceo-DiFrancesco, Mary K. Kochlefl, and Janice Walker, "Fostering Inclusive Teaching: A Systemic Approach to Develop Faculty Competencies," Journal of Higher Education Theory and Practice 19, no. 1 (March 2019): 39, 31. Jump back to footnote 16 in the text.

- Debra Sellheim and Mary Weddle, "Using a Collaborative Course Reflection Process to Enhance Faculty and Curriculum Development," College Teaching 63, no. 2 (May 2015): 52–61. Jump back to footnote 17 in the text.

Chris Gamrat is a Senior Instructional Designer at Penn State University.

Sonia Tiwari is a Research Specialist at Penn State University.

Saliha Ozkan Bekiroglu is a User Experience Researcher at Artech.

© 2022 Chris Gamrat, Sonia Tiwari, and Saliha Ozkan Bekiroglu. The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 International License.