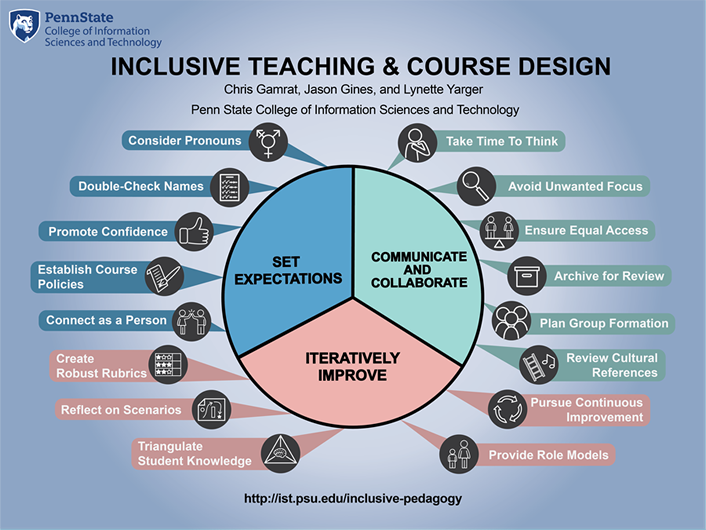

Faculty and instructional designers can employ a number of strategies to create courses and learning environments where students feel welcome and connected.

As an instructional designer, I've thought a lot about the value of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) in the context of teaching and learning. But where to start? Determining how best to incorporate DEI into course design and teaching was overwhelming. I began by reading articles and attending workshops, but I still felt that while I was gaining perspective on students' needs, I didn't know how to focus my energy to effect change. That is when I decided to create a list of considerations to help faculty and instructional designers create courses and learning environments where students feel welcome and connected.

While the following list is not comprehensive, it includes considerations for a broad spectrum of students who are or become minoritized or marginalized for various reasons (e.g., gender, race, ethnicity, or military status) or classifications (e.g., first-generation college students or English as a second language students). I hope that these recommendations and examples offer faculty and instructional designers a new perspective on student needs and strategies for creating a caring learning environment.

Setting Expectations on the First Day

Faculty can use a number of techniques to connect with students on the first day of class and show students that they care.

- Connect as a person. Take the time to recognize that faculty and students all enter the course with a unique set of experiences, that life happens, that everyone has off days, and that, as their instructor, you care about their academic success. An important part of the student experience is the interactions students have in the classroom with the instructor and other students. Recognize the value that each student brings to the shared course experience.

- Promote confidence. Students are in class for a reason. Freshmen have made it past the hurdle of admissions, and upperclassmen have met the requirements for their major. Remind students that with hard work, they can achieve a great deal and that they belong in the class.

- Double-check names. Some students have nicknames; others may be exploring their gender identity. There are a variety of reasons that a student's preferred name may not be the name found in the student information system. Offer students an opportunity to provide a preferred alternative name. Students may also have names that are unfamiliar to you. If so, ask them for pronunciation help or search online for audio clips that can help you practice the pronunciation of unfamiliar names. Asking for and using a preferred name can be an effective way for you to help students feel welcome and valued.

- Consider pronouns. Consider adding your pronouns to the contact information in your syllabus and invite students to optionally share their own. Let students know that they can elect to provide this information at any time during the semester. Asking students to provide their pronouns as part of the introductions on the first day of class can unintentionally put students in a position of having to identify on the spot. Because some students are still exploring their identity, it might be better to tell students that you recognize the importance of being called the right pronoun and that they can always reach out to you to make sure this happens in your class.

- Establish course policies. Including a diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) policy in your syllabus not only shows your commitment to your students, but it also establishes acceptable classroom conduct for students. Review existing policies and modify them where necessary to promote a positive, supportive, and inclusive learning environment for all students. Remind students that everyone in the class is navigating the course as imperfect humans; you (and they) may not always get things right, but the intent is to foster a respectful space where everyone can learn from each other and from each other's mistakes.

Laying the Groundwork for Respectful Communications and Collaborations

- Review cultural references and examples. Provide multiple examples that include a variety of cultural references and elaborate on cultural references when possible. Students may get confused when instructors make references to popular culture or university culture. When you make such references, consider the assumptions you are making about what the students might already know. Students who are from different generations or geographical areas may not understand the cultural references used in course examples. Also, first-generation college students are new to academic life and may not understand the internal workings of higher education institutions. Multiple examples and elaborations can help students gain clarity and achieve a lesson's learning objectives.

- Avoid unwanted focus. Try not to make students who are in the minority in your class inappropriately visible. While class conversations might benefit from the perspective of specific students in your course, avoid singling out students by asking for "an African American perspective" or "a woman's perspective." Instead, invite everyone to contribute diverse opinions that may be missing from the conversation, even if you assume that a topic is more relevant to some students than it is to others.

- Plan group formation. Group formation through student self-selection opens the possibility for some students to be excluded. Consider randomly assigning groups or using other methods to organize students into groups, such as forming groups based on shared interest in a topic. Provide opportunities for students to report issues with their groups and a mechanism for reassigning groups when necessary.

- Take the time to think. Silence can be used to give all students time to reflect before they speak. Such reflection time can help students to formulate their ideas and share more, and not just follow the first suggestion offered in a group discussion. Individual reflection also slows down the "get it done" mentality by showing that thoughtfulness is valued over speed.

- Archive for review. Capturing lesson content for later review and further reflection can be beneficial to many students, particularly those who are non-native speakers or those with physical disabilities (e.g., deafness) or cognitive disabilities (e.g., attention deficit disorder). Students can review a recorded lesson multiple times if they need to clarify one or more points. In keeping with universal design principles, video recordings should be captioned so that students can more easily process the lessons.

- Ensure equal access. Communicate high standards for student learning and achievement and tell students how to access supplemental learning materials and support resources to help them achieve those standards. Such resources might include contact information for academic advising, peer tutoring, writing centers, career services, and student health services. You could provide access to this information on your course page and set aside time in class to direct students to these resources. Also, if you answer a question from one or more students about the course, consider sharing your response with the entire class so that everyone can benefit.

Making Iterative Improvements to the Course Design Structure

- Reflect on scenarios. When creating scenarios for projects, quizzes, and exams, consider including diverse names and more than one gender in the scenarios. Also, consider the context of your scenarios and try to avoid stereotyping.

- Triangulate student knowledge. Consider the ways that you measure student knowledge. Some students experience anxiety from testing or speaking in a large group, and student performance may not fully represent how well they met a given learning objective. Multiple modes of measurement (quizzes, projects, papers, presentations, etc.) can help to better represent students' progress (it's also another element of universal design for learning). Utilizing multiple, low-stakes assessments through a variety of means provides a clearer picture of the knowledge and skills students develop in a course. Increasing the number of assessments also provides more opportunities for feedback and improvement and reduces the stress associated with any single assessment.

- Create robust rubrics. This might seem obvious, but fair grading can be clarified through rubrics that outline faculty expectations for students. Setting these expectations for a course helps to ensure that instructor feedback and grades are fair and consistent, and that peer evaluations are consistent and equitable.

- Provide role models. Students can benefit from having role models in their field—people who students can identify with and who can help students see a path to success. Where possible and relevant, include diversity in your guest speakers, readings, and video content. When students see broad representation in their field of study, they will begin to see how they could be part of the field, too.

- Pursue continuous improvement. Consider taking workshops and engaging in other professional development opportunities to improve your understanding of students, including how best to support their needs. Share your work with other faculty and instructional designers to promote what adjustments have worked well for your students. As with other aspects of your courses, consider ways in which you can improve your understanding of students and your instructional techniques from semester to semester.

Understanding the Most Important Step

When designing courses and teaching with a mind toward inclusive practices, I believe that the key is step 16: pursue continuous improvement. Whether you feel ready to tackle one or all of the suggestions listed above, remember that there is always room for improvement and more things to learn. Iterating your course design and teaching practices shows that you are responsive to students' needs, the climate of their chosen field, and a changing world.

For more insights about advancing teaching and learning through IT innovation, please visit the EDUCAUSE Review Transforming Higher Ed blog as well as the EDUCAUSE Learning Initiative page.

Chris Gamrat is an Instructional Designer at Penn State University.

© 2020 Chris Gamrat.