Simply having access to data doesn’t lead to an increase in the use of data to make decisions. Rather, the path to the effective use of data to support decisions starts with an understanding of the problems to be solved.

Drake University is a doctoral-professional university in Des Moines, Iowa. Founded in 1881, it has been coeducational and international from the beginning. Drake was founded to combine traditional study in the liberal arts with science, law, and other professional fields. Drake remains focused on combining the liberal arts with professional preparation. It offers more than 70 undergraduate and 20 graduate degrees in Arts and Sciences, Business and Public Administration, Education, Journalism and Mass Communication, Law, and Pharmacy and Health Sciences. It is ranked as one of the top 10 midsized universities in the country by the Chronicle of Higher Education.

The Challenge/Opportunity

Having a "data warehouse in a box" might sound appealing to many institutions as an easy solution to their data-driven decision-making needs. You purchase a self-contained data solution from a vendor—the "data warehouse in a box"—and rather quickly and easily your institution's staff and leadership have easier access to all the data they could ever need to answer any questions they might ever have. Simply plug in a question and out pops your answer.

However, according to Drake University's Chief Information Technology Officer, Chris Gill, and Director of Institutional Research and Assessment, Kevin Saunders, this solution, in and of itself, is grounded in a basic misunderstanding of the path to decision-support maturity and can often result in inconsistent or even little or no data adoption for decision-making across the institution. In merely providing easier access to data for your institution, one assumes that access to data is the institution's biggest barrier to meaningful and systematic data adoption. "If I can give my leaders and staff more access to data," the assumption goes, "the rest will take care of itself, and everyone will go to the same source to find the data they need whenever they need it."

Both Gill and Saunders made the mistake earlier in their careers of taking this "access first" approach to data-driven decision-making at their institutions (prior to his appointment at Drake, Gill was leading this work at Gonzaga University), with disappointing results. As can be the case at many institutions, they found that individual departments across their institutions already had their own deeply ingrained, siloed data preferences and habits—using their own Access tables, Excel spreadsheets, or whatever other disparate solutions they could patch together on their own—leaving key stakeholders skeptical of the value of learning a new data warehouse tool when their existing solutions already worked well enough for them.

"At both Drake and Gonzaga, no one knew what to do with [our new data warehouse solution]," Gill shared. "They didn't know what problems they could use it to solve."

Indeed, early in their collaborations at Drake, Gill and Saunders came to the realization that meaningful data adoption across the institution is driven more by the problems or needs leaders and staff have than by easier access to more data. In other words, rather than providing access to data in search of a problem to solve, the Drake team recognized they should be reaching out to understand their stakeholders' needs and then working collaboratively with those stakeholders to identify the data that would help them address those needs.

Process

For Gill and Saunders, the journey to improving data and decision-making maturity at Drake didn't begin with an outside catalyst or request. "Nobody came to us and said that they have this need from us," Gill said. Rather, Gill and Saunders had to take it upon themselves to work proactively to address a data maturity need they identified but that other stakeholders at the institution either weren't necessarily aware of or weren't otherwise prioritizing.

Moving beyond their "access first" approach to data maturity, they began the process of reaching out to individual units at Drake and asking key stakeholders what problems they were facing and what data reports they would need to help address those problems. Working with the provost, for example, Gill and Saunders took the time to reflect on the unique features of the provost's job, as well as the problems and needs she was facing, and began prioritizing a small list of simple data reports that would help provide her with the information she would need to better do the work of being a provost. Taking this "problem first" approach to data and decision maturity, they observed renewed enthusiasm for using their data solutions and suddenly began to find success in achieving more strategic and widespread decision-making maturity.

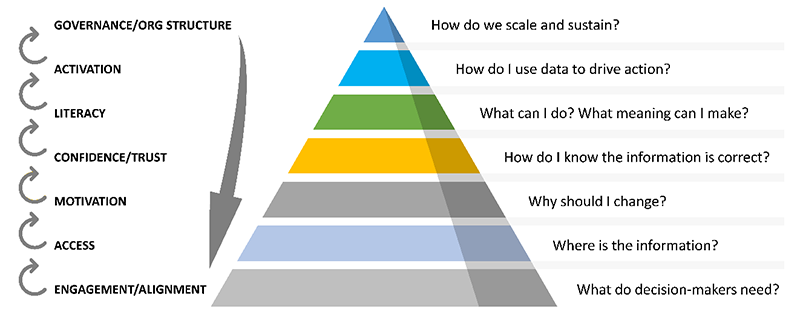

Adapting a list of questions from EAB into a decision-support maturity model, Gill and Saunders formalized their learnings in the form of the decision-support pyramid illustrated in figure 1 below. Key to this pyramid maturity model, access is nested as only one of several factors critical for decision-making maturity, rather than standing alone as the sole or primary factor, as it had in their earlier experiences. Just as critical for decision-making maturity, they had discovered, were factors such as data governance, data reliability, and (as highlighted in the above stories) engagement with key stakeholders' interests and needs.

With a better understanding of how data-driven decision-making could mature and take hold at their institution, Gill and Saunders were positioned for more effective, and more ambitious, institution-wide data implementations. Their Academic Financial Analysis project, initiated more than two years ago, was one such ambitious data project that sought to utilize Blackboard's Cost of Instruction (COI) tool to enable academic units across the institution to make more informed decisions about their programs based on their financial performance. With the trust they'd gained from their institutional leadership, Gill and Saunders were given two years of space to painstakingly work through important steps such as building and testing their data models to ensure their tool would provide valid and meaningful data to their stakeholders.

With a valid data tool developed, tested, and in place, Gill and Saunders began the equally critical work of building enthusiasm and buy-in, first from their president and provost and then from the deans of each of Drake's colleges. Located at the "Activation" level of the decision-support maturity model, these conversations helped the deans understand precisely what the COI data could tell them and how the data could be translated into action to help each college reach its financial targets. Through these conversations, Gill and Saunders observed academic units taking ownership of their data and becoming proactive in shaping meaningful questions to take to those data. In these ways, key stakeholders became partners in the institution's data-driven decision-making rather than targets or victims of it.

Gill reflected on this transformation among the academic leadership: "All of a sudden it turned from 'We're scared that an admin is going to use [these data] to close programs' to 'How do we better understand our decisions to position ourselves for success,' and the ownership for that resides within the unit."

Outcomes and Lessons Learned

- Information Technology and Institutional Research are natural (and critical) partners. Without forming a trust-based, collaborative partnership as their first step, little of what Gill and Saunders were able to accomplish would have been possible. They have focused on nurturing and strengthening that partnership at each step of their journey.

- Cultivate clarity and transparency. When communicating with key stakeholders about new data tools, Gill and Saunders recommend ensuring that those stakeholders clearly understand the purpose of the data and how the data will be used, as well as ensuring that the terminology and methodology used to collect, analyze, and interpret the data are shared and understood. Uncertainty and lack of information can breed fear and resistance among stakeholders, especially in contexts where data may be needed to make difficult business decisions for the institution. Frequent, clear, and transparent communications can help allay those feelings among stakeholders.

- Understand the context and be attentive to change management. Gill and Saunders recognized that they were more than simply "purveyors of data." They were part of an institutional ecosystem with its own unique history and culture and leadership dynamics that would require its own unique approach to understanding the needs of stakeholders and helping guide them through difficult changes to the ways in which decisions get made. As Gill put it, "You can never put enough attention into change management."

- Leaders matter, but so do other stakeholders. The buy-in and support of the president and provost were key to success in improving the use of data at Drake, and Gill and Saunders would be the first to acknowledge their good fortune in having supportive leadership. But meaningful, lasting changes at Drake really started to occur when deans and department chairs began to approach their data seriously and with the intent of using those data to impact real decisions within their units. Gill and Saunders put in the hard hours to ensure staff at all levels of the institution understood their data and what they could do with those data, resulting in more widespread and meaningful adoption of data across the institution.

Mark McCormack is Senior Director of Analytics & Research at EDUCAUSE.

Chris Gill is Chief Information Technology Officer at Drake University.

Kevin Saunders is Director of Institutional Research and Assessment at Drake University.

© 2021 EDUCAUSE. The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 International License.