Almost two years after its release, the EDUCAUSE CIO's Commitment on Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion has attracted more than 550 signatures. Many in the higher education technology workforce report benefiting from DEI actions included in the statement, but more progress is needed.

EDUCAUSE is helping institutional leaders, IT professionals, and other staff address their pressing challenges by sharing existing data and gathering new data from the higher education community. This report is based on an EDUCAUSE QuickPoll. QuickPolls enable us to rapidly gather, analyze, and share input from our community about specific emerging topics.1

The Challenge

In October 2018, EDUCAUSE introduced the CIO's Commitment, a national campaign asking senior higher education IT leaders to jointly endorse a common set of actions that promote diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) locally and in the field. The commitment consists of six actions CIOs resolve to take. In the 21 months since the CIO's Commitment debuted, more than 550 people have signed it. As anyone who has made a New Year's resolution knows, the gulf between intention and execution can be depressingly wide. To what extent are CIOs actually delivering on the six commitments, from their own viewpoints and from those of the technology workforce?2

The Bottom Line

While many IT leaders have signed the CIO's Commitment, more efforts are needed to act on those commitments. Not enough people work in higher education technology organizations that are actively working to create diverse, equitable, and inclusive work environments. They deserve better, and CIOs need to do more to help. DEI is not as easy as technology: it requires many different ongoing activities and calls on technology leaders to display skills in communication, influence, partnership, and empathy that many were neither trained nor promoted for. Yet progress is both possible and ongoing: many technology staff and leaders reported progress and focus on DEI, citing training and events, leadership, hiring practices, metrics and accountability, and dedicated resources as contributors to that progress. Patterns in the data suggest that staff at private and doctoral institutions see their CIO doing more to advance DEI than staff at two-year colleges.

The Data: Support and Commitment for DEI

DEI has strong support in the higher education technology workforce. The technology leaders and professionals who responded to this survey believe in and are committed to advancing diverse, equitable, and inclusive workplace environments (see table 1). About 8 in 10 respondents reported the strongest agreement with four statements from the CIO's Commitment preamble about the benefits of DEI. Another 14–21% percent were in agreement (rather than strong agreement). Fewer than 1% of the people who responded to the survey disagreed with the four statements. Our polling sample isn't representative of national demographics, and support for DEI is probably overrepresented in this poll. Still, even a year ago, the Pew Research Center found that 77% of American adults felt that racial and ethnic diversity is very good for the country.3 We identified no institutional or individual differences in agreement levels with these statements.4

Table 1. Support and commitment for DEI

|

Statement |

Strongly agree |

Agree |

Neutral |

Disagree/ Strongly disagree |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Diverse, equitable, and inclusive workplace environments benefit everyone. |

83.2% |

14.6% |

1.6% |

0.6% |

|

Diverse, equitable, and inclusive workplace environments foster more effective and creative teams of technology professionals. |

83.1% |

13.7% |

2.5% |

0.6% |

|

The values of diversity, equity, and inclusion are personally important to me. |

78.5% |

19.3% |

1.6% |

0.6% |

|

I am committed to helping enhance opportunities for people of color, women, members of the LGBTQ community, people with disabilities, and others to fully participate in the technology professions at my institution. |

77.4% |

20.7% |

1.6% |

0.3% |

The Data: Current State of the Six DEI Commitments

When CIOs sign the commitment on DEI, they are resolving to take six actions:

- Raise my personal awareness about challenges and opportunities related to DEI in the technology field, and work to raise awareness departmentally and institutionally.

- Work to increase opportunities for women, people of color, members of the LGBTQ community, and individuals with disabilities to be information technology professionals and leaders.

- Work with EDUCAUSE and other professional organizations to encourage efforts to make transparent and publish technology workforce demographic data.

- Become aware of institutional and/or regional demographic trends and work toward creating an institutional and/or regional technology workforce that keeps up with demographic trends.

- Partner with institutional colleagues to create/advance programs that aim to expand opportunities and eliminate the barriers for students from underrepresented populations interested in computer science, data sciences, other technology-related fields, both in undergraduate education and post-graduation programs.

- Advocate for DEI practices, help develop appropriate DEI practices, resources, and tools, and mentor colleagues seeking to contribute to DEI efforts.

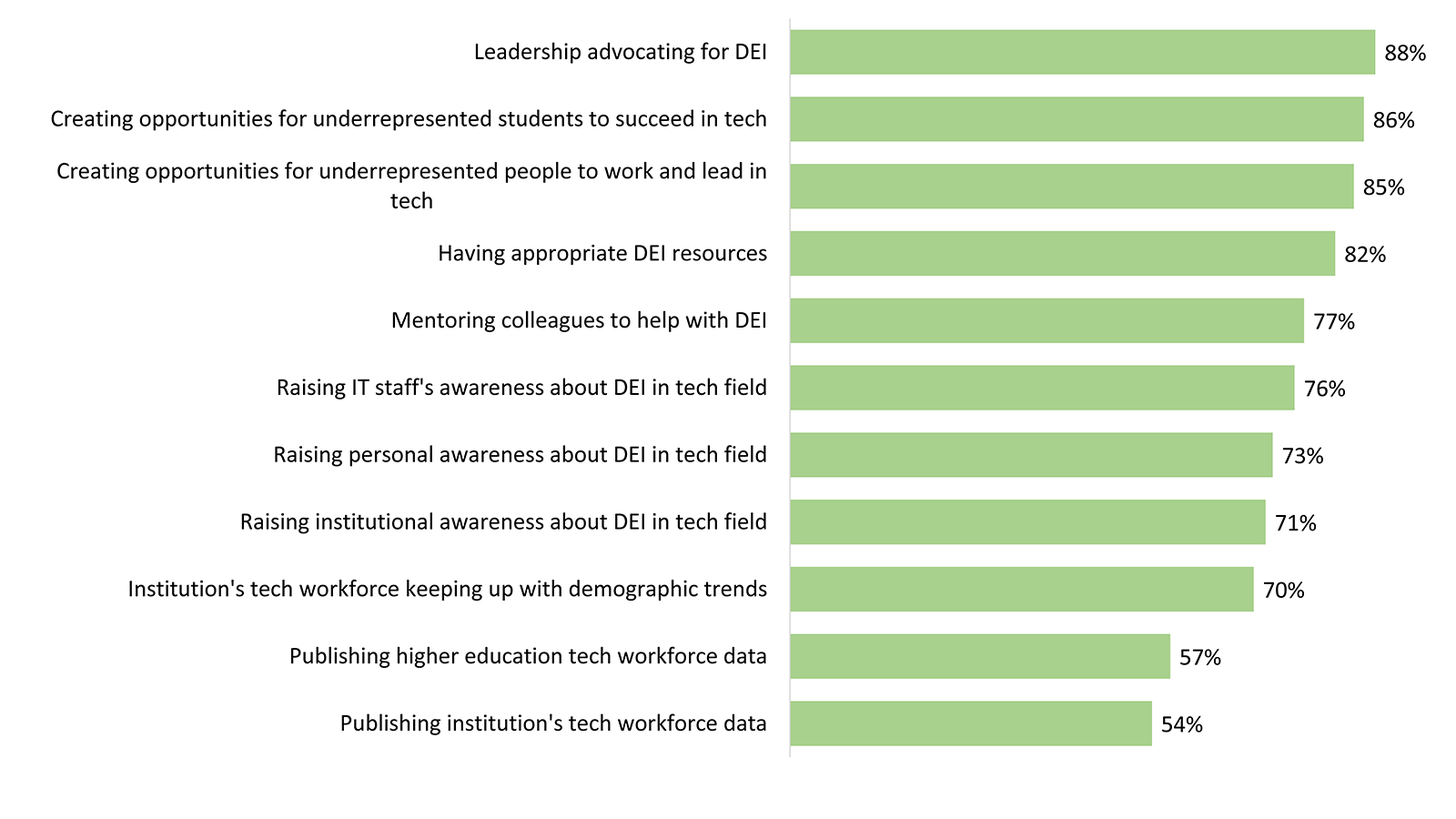

Leadership, opportunities, and resources are the most crucial actions in the CIO's Commitment. The survey asked about 11 specific actions that collectively reflect the six commitments. More than half of CIOs and technology staff felt that every action was crucial or very important for advancing the diversity, equity, and inclusion of the higher education technology workforce (see figure 1). Four actions in particular were almost universally view as crucial or very important: IT leadership advocating for DEI practices; increasing programs to create opportunities and reduce barriers for underrepresented students to succeed in computer science, data sciences, and other technology-related fields; creating more opportunities for people of color, women, members of the LGBTQ community, individuals with disabilities, and others to be technology professionals and leaders; and having appropriate DEI practices, resources, and tools. Least important (rated as crucial or very important by fewer than 6 in 10 respondents) were publishing and sharing demographic data about the institutions' or the higher education technology workforce.

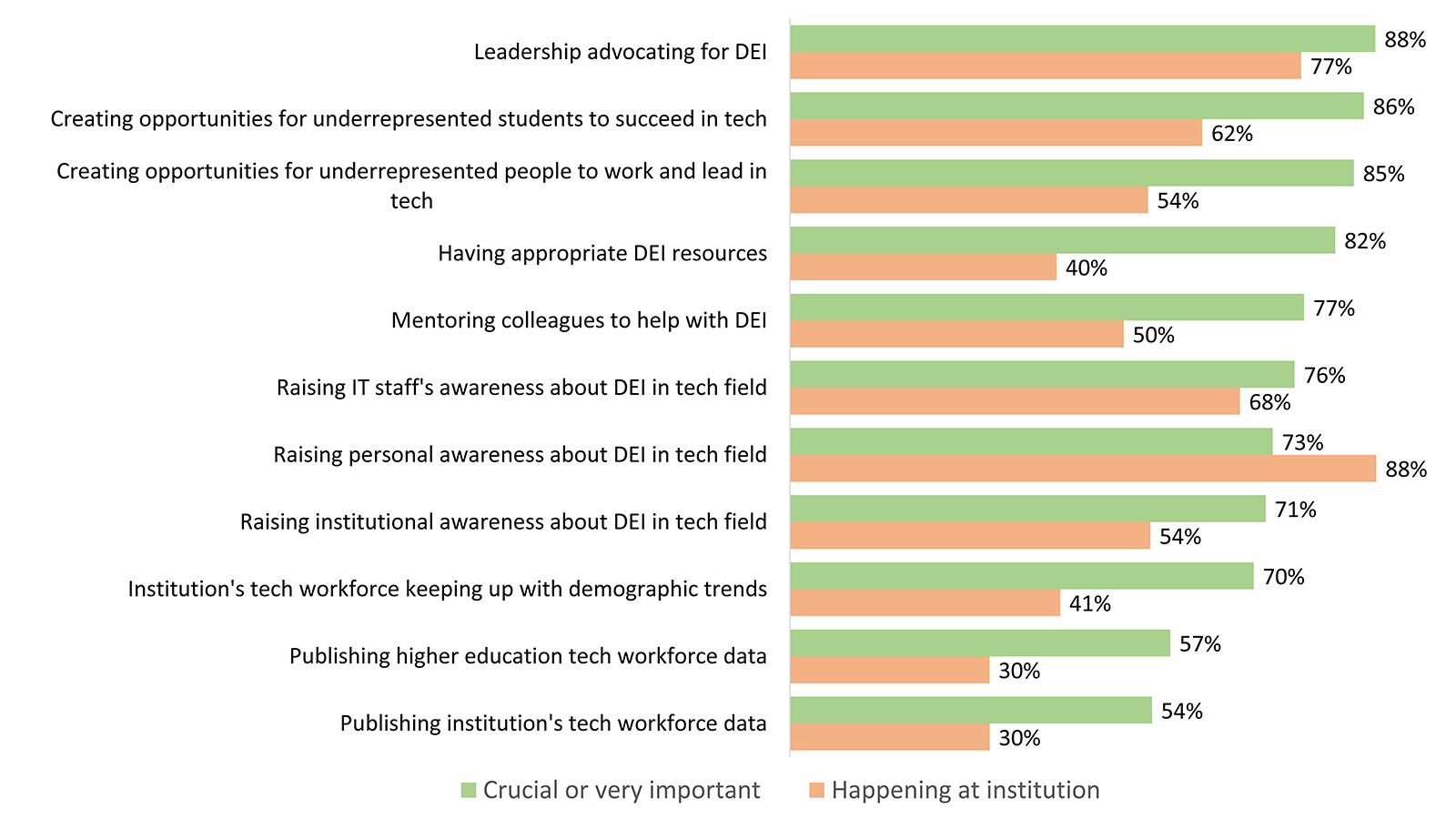

Large gaps exist between the perceived importance of DEI actions and how widespread they are. Although the average importance of the 11 commitment actions was 74%, the average actual occurrence of the actions was just 54% (see figure 2). The smallest gaps between importance and occurrence pertained to leadership and awareness. The largest gaps were for having appropriate practices, resources, and tools; creating more opportunities for people of color, women, members of the LGBTQ community, individuals with disabilities, and others to be technology professionals and leaders; becoming an institutional technology workforce that keeps up with institutional and/or regional demographic trends; publishing and sharing demographic data about the higher education technology workforce; and mentoring colleagues seeking to contribute to DEI efforts.

We found a few institution-level and individual differences in respondents' experiences. People at private bachelor's institutions and of Asian/Pacific or White/Caucasian ethnicity were more likely to feel that the IT organization leaders and staff are aware of the challenges and opportunities related to DEI in the technology field than people at public bachelor's institutions and those who are Black/African American, Hispanic/Latino, or multiracial/multiethnic. People who reported their sexual orientation as gay or straight were more likely than those identifying as bisexual to feel

- that their institutional community is aware of the challenges and opportunities related to DEI in the technology field;

- that people of color, women, members of the LGBTQ community, individuals with disabilities, and others have sufficient opportunities to be technology professionals and leaders at their institution;

- that their institution's technology units and organization(s) have appropriate DEI practices, resources, and tools; and

- that their institution provides opportunities and support for mentoring/being mentored to contribute to DEI efforts.

People who identify as Black/African American, Hispanic/Latino, or multiracial/multiethnic expressed lower rates of agreement than Asian/Pacific or White/Caucasian respondents that the IT organization leaders and staff are aware of the challenges and opportunities related to DEI in the technology field and that people of color, women, members of the LGBTQ community, individuals with disabilities, and others have sufficient opportunities to be technology professionals and leaders at their institutions. More people at two-year institutions reported that their institution provides opportunities and support for mentoring/being mentored to contribute to DEI efforts than people at public bachelor's institutions. More people at private bachelor's institutions felt that the IT organization leaders and staff are aware of the challenges and opportunities related to DEI in the technology field than did people at public bachelor's institutions.

The Data: The CIO's Role in Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

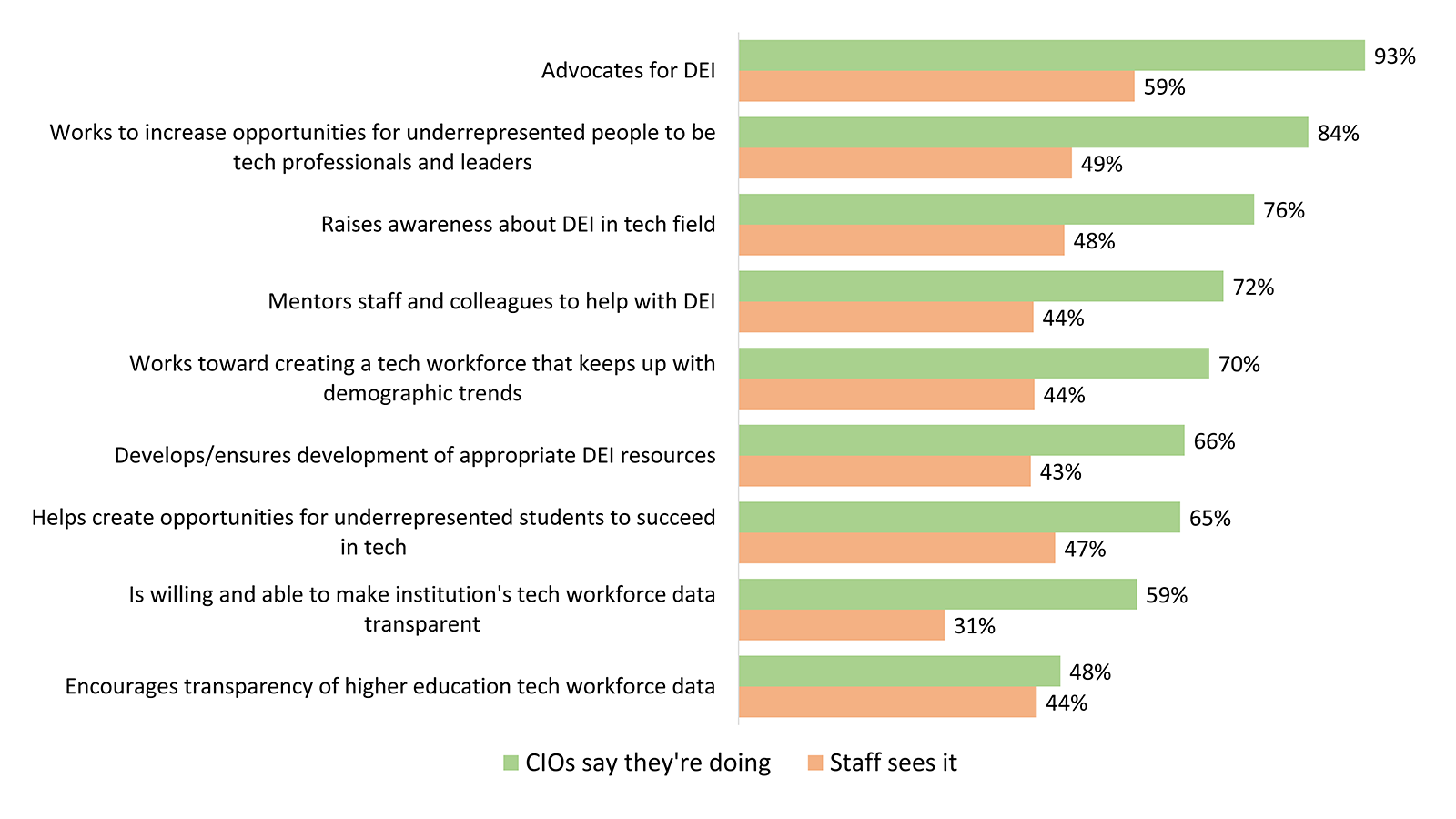

In general, CIOs describe themselves as active and effective proponents of DEI, but many members of the technology staff assess the IT leaders at their institution less favorably. Most of the 126 CIOs who completed the survey felt they were living up to most of the actions in the CIO's Commitment (and two-thirds have signed it), particularly in advocacy and working to increase opportunities for women, people of color, members of the LGBTQ community, individuals with disabilities, and others to be technology professionals and leaders (see figure 3). With one exception (advocating for DEI practices), fewer than half of technology staff viewed their CIO as taking such an active role in improving DEI. Perhaps the most likely explanation for this gap is that CIOs who are not particularly interested in DEI did not participate in the survey but that members of their staff did.

We found consistent institutional differences in staff's assessment of their CIO's contributions to DEI (see table 2). Staff at two-year colleges consistently rated their CIOs as doing less to support DEI. CIOs at private and doctoral institutions were often seen as more active.

Table 2. Assessments by IT staff of their CIO's DEI activities

|

CIO Activity |

Institution types with higher levels of staff agreement |

Institution types with lower levels of staff agreement |

|---|---|---|

|

The CIO/senior IT leader is working to raise awareness of the challenges and opportunities related to DEI in the technology field. |

|

|

|

The CIO/senior IT leader is working to increase opportunities for people of color, women, members of the LGBTQ community, individuals with disabilities, and others to be technology professionals and leaders. |

|

|

|

The CIO/senior IT leader is working with EDUCAUSE and other professional organizations to encourage efforts to make transparent and publish demographic data about the higher education technology workforce. |

|

|

|

The CIO/senior IT leader is working toward creating an institutional and/or regional technology workforce that keeps up with demographic trends. |

|

|

|

The CIO/senior IT leader is partnering with institutional colleagues to create opportunities and reduce barriers for underrepresented students to succeed in computer science, data sciences, and other technology-related fields. |

|

|

|

The CIO/senior IT leader advocates for DEI practices. |

|

|

|

The CIO/senior IT leader helps develop DEI practices, resources, and tools. |

|

|

|

The CIO/senior IT leader mentors staff and colleagues seeking to contribute to DEI efforts. |

|

|

Individual staff characteristics were not associated with assessments of the CIO's role in DEI, with one exception. Baby Boomers were more likely than Millennials to agree that their CIO helps develop DEI practices, resources, and tools and is partnering with institutional colleagues to create opportunities and reduce barriers for underrepresented students to succeed in computer science, data sciences, and other technology-related fields.

Promising Practices

Creating a diverse, equitable, and inclusive workplace requires sustained commitment and multiple investments. When we asked respondents to describe particularly helpful actions being taken by their IT organization to increase diversity, equity, and inclusion, they wrote most often about training, events, and awareness-building:

- "Our internal DEI team hosts events including an annual film festival. This year—in fact, this week—we will come together having watched relevant video content to discuss it openly with a campus expert on driving open conversations. Throughout the year, we find ways to make those conversations happen—community building is a huge part of our efforts."

- "We regularly read and discuss DEI topics. Our CIO has hosted a weekly DEI conversation since 2017."

- "We have done LGBTQIA training, which was extremely helpful because it was everything you always wanted to know but where afraid to ask."

A dedicated team and an institution-level focus were other helpful actions. Very often these efforts were organic rather than officially convened:

- "A grassroots committee was formed to help educate IT staff about DEI."

- "We have university (more than technology) leadership talking about DEI through town halls and educational material aimed at faculty and staff."

- "There's a DEI committee that posts learning resources and occasionally does trainings like unconscious bias. It's a start."

Moving beyond awareness activities, respondents also described efforts to influence hiring and improve accountability:

- "We include DEI as part of performance management. We hold everyone accountable. We require bias training for all search committee members prior to review materials or interviewing candidates."

- "We have adjusted our job advertisements and descriptions to be more inclusive; we've changed our interviewing practices for the same reason."

- "Everyone at the director level must have an active part of their job description devoted to inclusion and diversity. If you are that level of leader, you are required to be a part of the solution. Positive annual reviews are then at least partially focused on what each director has done to ensure their supervisors, staff, and hiring committees are focused on being a part of improvement efforts."

- "The central IT organization has excellent HR practices. Serving on their search committees is great professional development for me and my staff."

Many respondents work in locations that are not very diverse and still find ways to build a more diverse technology workforce:

- "Our institution is located in a very non-diverse area, so it has been difficult to diversify the IT organization by hiring within the region; we have brought diversity to the organization through our student technology assistant program, which draws students with interest in technology, sciences, analytics."

- "Advocates on search committees to increase recruiting a diverse workforce. Opportunities for K–12 outreach related to creating a more diverse pipeline."

- "Working with local organizations to create internship and mentoring opportunities for interested parties."

Common Challenges

Many feel stymied by a limited pipeline. Many respondents felt the lack of current diversity in their region or in the field deters more diversity:

- "We don't have a lot of diverse applicants."

- "Candidate pools do not contain enough qualified underrepresented applicants."

- "Demographics in this area are not very diverse; 11% African American, very small percentage Latino, neglible other ethnicities. Difficulty in reaching DEI candidates."

- "The technology field as a whole is not diverse and does not have a pipeline that encourages diversity."

- "Regionally, it is difficult to attract the best-qualified candidates in racial minorities. Even if [the institution is] welcoming, the ethic and cultural diversity of the city and local areas is not a strength."

Disinterest, lack of commitment and leadership, and bias are the biggest deterrents. Many respondents despaired about leadership and an insitutional culture that had overt or implicit biases or that simply didn't have the time or interest in developing a diverse, equitable, and inclusive workplace.

- "A white male CIO who hires only white males."

- "There's no patience for trying to imagine a better culture that's inclusive and welcoming and DIVERSE. There's more white guys named Brian/Bryan than women in most departments. Let alone non-white hires."

- "DEI being seen as an additional burden, something separate from our work or not as important as strategy, security, operations, budget, etc."

- "All DEI efforts are seen as what the minorities (women, POC, LBGTQ, etc.) can do to better position themselves for success rather than what the IT organization needs to do to be more diverse, equitable, and inclusive."

- "Boys-club mentality, with men given opportunities to take on more technical roles and given mentorship. Women get stuck in projects and tasks less technical."

- "Clueless management. They favor one group at a time. Currently, you can only advance by being female."

Human resources is a make-or-break partner. Respondents described human resources (HR) as a crucial partner in advancing diversity. A number of comments, sadly, detailed the lack of support HR provided:

- "The applicant management system my university purchased does not support resume blinding, and HR doesn't provide best practices for doing that kind of work. There is training and support for conducting fair and inclusive faculty searches, but not for staff searches. We are not allowed to put our own diversity statement in our job ads. It feels like HR treats DEI as an inconvenience, an unnecessary complication instead of as a way to improve our workforce."

- "Our recruitment process could use consistency—review of position descriptions to increase diversity in applicant pools, consistent blinding across all groups, anti-bias training across all groups. We are a large university with distributed HR and distributed IT, but finding a way to make anti-bias practices the standard rather than the exception would help."

- "One barrier is HR policy and practices. The very nature of how jobs are posted, how candidates are reviewed and selected, how interviews are conducted, etc., does not allow for de-identified candidates. HR is in fact resistant to doing that, even to potentially reduce bias."

Research demonstrates that a diverse, equitable, and inclusive working environment benefits everyone.5 This QuickPoll indicates that many staff do not see their CIO living up to the six elements of the CIO's Commitment. It is time for every CIO to do so.

All QuickPoll results can be found on the EDUCAUSE QuickPolls web page. For more information and analysis about higher education IT research and data, please visit the EDUCAUSE Review Data Bytes blog, as well as the EDUCAUSE Center for Analysis and Research.

Notes

- QuickPolls are less formal than EDUCAUSE survey research. They gather data in a single day instead of over several weeks, are distributed by EDUCAUSE staff to relevant EDUCAUSE Community Groups rather than via our enterprise survey infrastructure, and do not enable us to associate responses with specific institutions. ↩

- The poll was conducted on July 13–14, 2020; 370 CIOs and technology professionals responded. The poll consisted of 20 questions and took respondents a median time of 7 minutes and 36 seconds to complete. Poll invitations were sent to participants in a wide range of EDUCAUSE community groups. A diverse range of institution sizes and Carnegie Classifications participated. The respondents described themselves as 55% female and 45% male; 78% White/Caucasian, 7% Black/African American, 6% Asian/Pacific Islander, 2% Hispanic/Latino, and 8% mixed or another racial/ethnic background; 84% straight, 9% gay, 4% bisexual, 2% queer, 1% another sexual orientation; 11% diagnosed with a disability; and 37% baby boomers, 50% generation X, 13% millennials, and less than 1% generation Z. ↩

- Juliana Menasce Horowitz, "Americans See Advantages and Challenges in Country's Growing Racial and Ethnic Diversity," Pew Research Center, May 8, 2019. ↩

- We looked at institution size, minority-serving, and Carnegie classification for institution-level differences. For individual differences, we examined generation, gender identity, ethnicity/race, sexual orientation, and whether people had been diagnosed with a disability or impairment. ↩

- Janine Schindler, "The Benefits of Cultural Diversity in the Workplace," Forbes, September 13, 2019; and Stephen Turban, Dan Wu, and Letian (LT) Zhang, "Research: When Gender Diversity Makes Firms More Productive," Harvard Business Review, February 11, 2019. ↩

Susan Grajek is Vice President of Communities and Research at EDUCAUSE.

© 2020 Susan Grajek. The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 International License.