Most organizations continuously seek to enhance efficiency, improve quality, and save time and money; however, they are not engaging in formal process-improvement efforts to achieve these things.

Process improvement (PI) goes by many different names—business process engineering (BPE), business process reengineering (BPR), and process analysis, just to name a few—and yet the desired outcome of all of these efforts is the same. Regardless of the terminology, the goals of PI are to enhance efficiency, improve quality (not only of the process itself but also the result of that process), and save time and money. Some PI efforts result in recommendations for large, transformative changes or even full system redesigns, and others identify simple, easy-to-implement opportunities. While the recommendations are an important deliverable of the PI effort, the analysis associated with the PI effort can often produce immediate positive organizational impacts. PI is unique in that it facilitates critical thinking among everyone involved. It opens lines of communication that were not previously leveraged, enlightens participants on aspects of the process that might be outside the scope of the participant's job responsibilities, and shines a light on issues that may have been ignored for a while. When done correctly, the PI effort inspires stakeholders to look at their processes with a more critical eye and motivates teams to work together to improve those processes.

PI efforts often yield a number of positive outcomes; however, PI efforts are not commonplace in every organization. Some leaders may think such efforts are too costly or time-consuming. Other leaders believe that PI efforts are unnecessary, perhaps because the organization is already aware of processes that need to be improved or because the organization lacks the resources (time, money, or people) to implement improvements. Many leaders believe they are already engaging in continuous PI efforts. They assume these efforts are embedded in everyday practices, or that PI is a natural part of other efforts, such as gathering requirements, discovery, strategic planning, and the like.

The assumption that PI takes place without a formal, directed effort is almost always inaccurate. While many other efforts incorporate some of the same techniques and principles as PI efforts—and also seek to make improvements—none focus on improvement with the same rigor and breadth. A specific trigger will often drive a project, and this trigger becomes the focal point for change. For example, let's say a new version of a piece of software becomes available, and it offers three new, desirable features. The move to the updated version of the software and the adoption of the new features often become the focus of the effort. Other challenges with the existing software get overlooked, and often the new features are not analyzed to see how they will impact the overall process. While it is important to plan for the future, PI examines the current state of the processes and existing needs and challenges in order to identify opportunities for improvement. PI facilitates a better understanding of the end-to-end process and the impact that the process has on an organization.

PI efforts are different from traditional business-analysis approaches. While other efforts are valuable and often necessary, PI takes a unique direction and focus to ensure that strategic and tactical needs are captured.

Put the Spotlight on Your Process

A process is anything that creates and delivers value in a consumable format. Process improvement focuses primarily on "why" existing processes are used and needed. Process analysis seeks to uncover, extract, and question why things are done a certain way. Other business analysis efforts focus on the mechanics of what and how tasks are accomplished, but such efforts often fail to focus on the question of why tasks are needed to begin with. The PI analysis deconstructs existing processes to help organizations understand the people, processes, tools, and data that support each step. The people, or stakeholders, are referred to as "actors" because they are the ones who play roles in the process. The list of actors is expansive and often includes customers and end users. PI helps organizations create "blueprints" from which a framework for change can be built. It involves brainstorming ideal ways of working by exploring current and past challenges and future needs. PI seeks to identify what is needed to create value and why it is needed, rather than the specific mechanics of how the value is delivered (that comes later). Deliverables from PI efforts usually include documentation about the existing practices (such documentation should highlight the challenges and inefficiencies that currently exist) and a set of recommendations for improvements that can be implemented at the discretion of process owners. Some non-PI efforts also take existing challenges into account when planning for the future, but unlike a PI analysis, these efforts fail to dig into the challenges and often do not trace a challenge back to the source. As a result, the wrong thing may be changed. Because PI emphasizes root-cause analysis, organizations can make effective changes, which ultimately improves the overall process.

Talk to Everyone Involved

Identifying all of the actors, or stakeholders, who are involved in a specific process may seem like a simple task, but often there are more people involved than had been initially identified. Process improvement efforts bring in a wide range of perspectives by interviewing all stakeholders, regardless of their level of involvement. Every person who touches a process—from the consumer to the support person at the end of the process—is considered an actor in the process. The list of actors should include even the most minor contributor to a process; if the work passes through an individual and they take any action on it, then they are an actor. Often, those who are identified as having minor roles have a much more significant impact on the process than originally thought. Everyone, from the person who is a top performer, or power user, to a person who complains and may be viewed as a naysayer, is equally important. Each individual has a unique viewpoint that is important to understand because perspective is a critical part of PI. Allowing each person to be part of the assessment empowers them to be a valued contributor to the solution, thus laying the foundation for change.

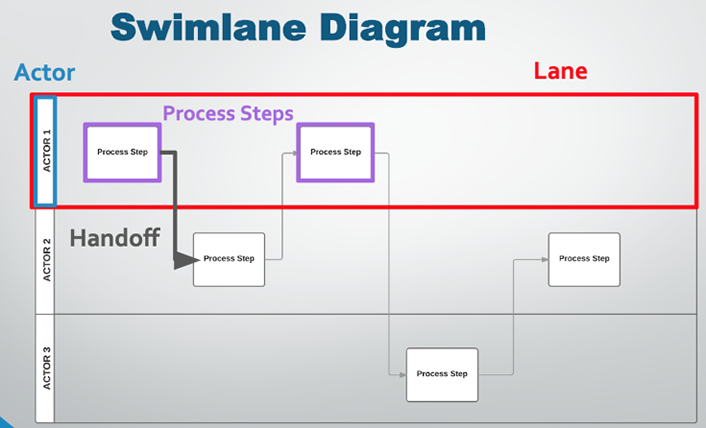

The actors in any process are often depicted in a swimlane model, which shows how the process moves from one person to another. A swimlane model is a great tool to help identify all of the actors in a given process and any gaps in the flow from one step to the next. For instance, an administrative assistant may not initially be identified as an actor, but the analysis may reveal that the assistant plays a vital role. Assistants, student workers, and temporary workers often handle manual and labor-intensive work that could be simplified. Overlooking anyone's involvement, in even the smallest part of a process, could result in missed opportunities for improvement.

"What?" "When?" and "Who?" questions often result in similar answers regardless of who is asked. Details obtained from asking these questions are important when documenting needs, but asking "Why?" often elicits answers that are unique to each actor's perspective and role in the process. Two stakeholders may perform the same tasks, but their reasons for why the task is done could be very different. Some actors may not be aware of what happens before or after they touch the process, and therefore have a limited perspective of the end-to-end process. The purpose of the conversations with the actors is to gain an understanding of their existing practices, challenges, and needs. The goal is not to document the fine details of exactly how tasks are performed but rather to understand the rationale and goals of actors' actions. Identifying all actors and documenting what and why they do what they do are often the most time-consuming parts of PI efforts. Nonetheless, this work is critical and reflects a strength unique to PI compared to other improvement efforts.

Consider the Process and the People in Addition to the Technology

Other analysis efforts often place a large emphasis on technology (tools and data)—what it can do, how it works, and what problems it will solve. For example, efforts to document requirements are frequently guided by system or product features because the catalyst for the effort is the suggestion of a new or enhanced tool. The effort involves researching and identifying the requirements or specifications needed, and these must be detailed and quantified so that they can be implemented in a new tool. The goal is for this new tool to improve the existing way of doing business.

Requirements documents will generally include new system efficiencies, but a narrow focus on technology may miss other improvement opportunities within the larger end-to-end process. Process improvement does not replace the need for technical documentation, but engaging in a PI effort prior to analyzing the requirements will streamline and complement that effort.

Process, people, data, and tools are all assessed with the ultimate goal of identifying existing challenges and business needs. Recommendations for improvement often involve much more than a technical solution. Time and resources are wasted when there is a mismatch between what is requested and what is needed. Many times, the assumption is that there is a need for all of the functionality that currently exists in addition to the new features. This assumes that what is there is optimized and necessary, and that is rarely the case. Focusing on new features can diminish existing processes, which may be riddled with issues. Countless software upgrade implementations have failed because the starting point is an antiquated, inefficient system. PI does not assume that any part of an existing process is perfect. Rather, the effort seeks to fully understand all of the business needs in order to ensure each need is documented and prioritized properly.

Obtain Better Results

Bringing together everyone who is part of the process and asking each person what they do and why they do it helps to challenge assumptions and shed outdated operational rules. "The way we have always done it" should be a trigger to dig further into the procedure to ensure it still makes good business sense. PI seeks to identify value and focus recommendations around needs and outcomes. It results in a big-picture assessment of existing processes and identifies tangible opportunities that can inform future needs. Speaking only to a small group of people or focusing attention on a very specific part of a process will cause critical details to be missed. An error of omission or a false assumption can result in huge time losses down the road. While a PI effort will add time to the front end of a project, it will ensure the correct organizational goals are prioritized and documented.

Some PI efforts result in recommendations that are aligned with what the business owners or leaders anticipate, and the independent analysis delivers actionable supporting information. Other times, the results of the PI effort are different from what the organization anticipated, and as a result, the project may take on a new direction. Even if the outcome is exactly what was predicted, speaking to the actors who contribute to the process and incorporating their unique perspective builds goodwill. PI efforts serve as an impetus for change by bringing people together to challenge assumptions, question actions, and work toward a common goal.

For more on enterprise IT issues and leadership perspectives in higher education, please visit the EDUCAUSE Review Enterprise Connections blog as well as the Enterprise IT Program web page.

Kristine Maphis is a Senior Process Consultant with University Process Innovation in the Division of Information Technology at the University of Maryland.

© 2020 Kristine Maphis. The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY 4.0 International License.