Across higher education, IT leaders have responded to the pandemic in ways both strategic and operational, and many believe that their increase in influence will be an enduring change.

As the COVID-19 pandemic upends higher education in 2020, institutions are relying on digital alternatives to missions, activities, and operations. Challenges abound. EDUCAUSE is helping institutional leaders, IT professionals, and other staff address their pressing challenges by sharing existing data and gathering new data from the higher education community. This report is based on an EDUCAUSE QuickPoll. QuickPolls enable us to rapidly gather, analyze, and share input from our community about specific emerging topics.1

The Challenge

The emergency technological solutions required to move institutions to both remote learning and work placed IT organizations center stage and have given information technology the opportunity to demonstrate its operational and strategic importance. As colleges and universities have changed in response to the pandemic, IT organizations have been faced with the need to respond nimbly, rethink services provided and organizational structures, and consider the role IT leadership plays in shaping the future of the institution. After several months of frenetic work to increase institutional capacity to deliver courses online and to empower staff and faculty to work from home, we pause to consider the impact that the pandemic has had on higher education IT leadership. Have the operational and the strategic influences of IT changed since the beginning of the pandemic? How has the importance and role of the CIO changed, if at all, and in what ways have these changes been manifested? How have senior IT leadership positions been changed, if at all, since the beginning of the pandemic? Are pandemic-induced reorgs on the horizon for higher education? And, how likely are any of these shifts to continue post-pandemic?2

The Bottom Line

As we recently discovered, higher education IT has not been protected from budget cuts stemming from the pandemic.3 Unfortunately, these cuts are occurring at a time when the importance of IT is increasing and is being recognized widely for its contributions to strategic outcomes. Our evidence strongly suggests that the pandemic has elevated the strategic role of IT and the CIO, including key components of the culture and workforce shifts that are part of digital transformation (Dx). Both the operational and the strategic influences of IT on campus appear to have increased—in some cases greatly—since the onset of the pandemic. Moreover, the pandemic has catapulted the importance of the CIO or senior IT leader to new heights. IT leadership’s engagement with the work of planning and innovating across the institution and managing IT operations and services has intensified. But despite all of the tumult of the past nine months, the leadership of IT organizations appears to be stable, with some minor adjustments to meet current needs. Most respondents told us that no reorganizations are in the works for the next year, but the ones that are planned result from the budgetary impact of the pandemic, were previously planned, or are expected as part of a leadership transition. Finally, most respondents are confident that the changes to or increases in levels of strategic influence they observe now will endure in a post-pandemic era, solidifying the strategic foothold of IT in higher education for years to come.

The Data: The Influence of IT

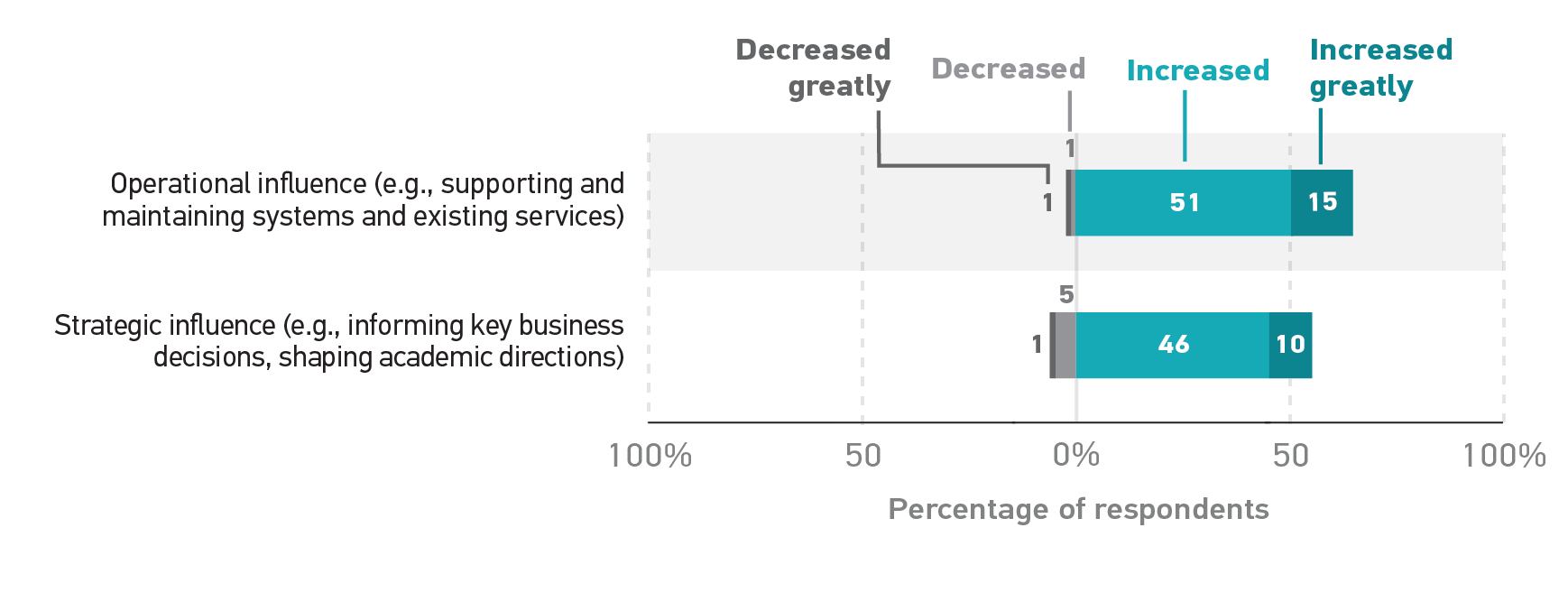

Both the operational and the strategic influences of IT have increased since the beginning of the pandemic. In his 2018 EDUCAUSE Review article “Strategic IT: What Got Us Here Won’t Get Us There,“ EDUCAUSE President and CEO John O’Brien maintains that the “utility mindset” of IT as infrastructure is insufficient to advance the strategic mission of higher education institutions.4 Although the tension between “plumber” and “strategist” is often couched in dualistic, or zero-sum, terms where attention to one necessitates ignoring the other, our evidence suggests that the pandemic is serving as a catalyst that requires attention to the operational and strategic simultaneously. Two-thirds (66%) of our respondents told us that the operational influence of IT at their institutions had either increased or increased greatly since the beginning of the pandemic. At the same time, a majority (56%) said that the strategic influence of IT also increased or increased greatly (see figure 1).

The increases in the operational and the strategic influences of IT appear to be inextricably linked. For many respondents, the boundaries between the operational and strategic functions of IT have become blurred as needs and projects have strategic importance that, in turn, reinforces the tactical:

- “We are more involved in campus efforts and are relied on more for coordination and new technology. Partners are coming to us earlier, and IT has been broadly recognized as a key part of how we teach online and make hybrid instruction work.”

- “[Our q]uick response to technical needs and an ability to execute has added both operational and strategic influence.”

- “We are seen as the ‘connective tissue’ of the institution, a key partner in making the pivot to remote teaching, learning, and administration.”

- “IT was a relied-upon partner and leader in helping the institution transition to remote teaching/learning/work; as such, our overall portfolio has grown significantly in support of existing and new services for campus, including classroom technology, collaboration tools, streaming capabilities, etc.”

The increases in operational and strategic influence are likely to endure post-pandemic. Respondents are moderately or very confident that the changes in the operational (84%) and the strategic (82%) influences of IT will continue post-pandemic. For these respondents, the pandemic response appears to have led to, as one respondent put it, an “enlightenment about the true role of IT.”

- “There is more appreciation for the importance of IT and its role as a strategic enabler.”

- “People across the institution are getting first-hand experience related to the key role IT plays (and had played) in university operations.”

- “The genie is out of the bottle, so to speak, and the faculty now understand better how technology can improve their students’ experience and help them manage their teaching activities.”

- “IT has gotten the chance to demonstrate our capacity to improve processes and collaborate to build solutions—we won’t be able to put that genie back in the lamp…there’s just too much demand.”

The Data: The Cabinet

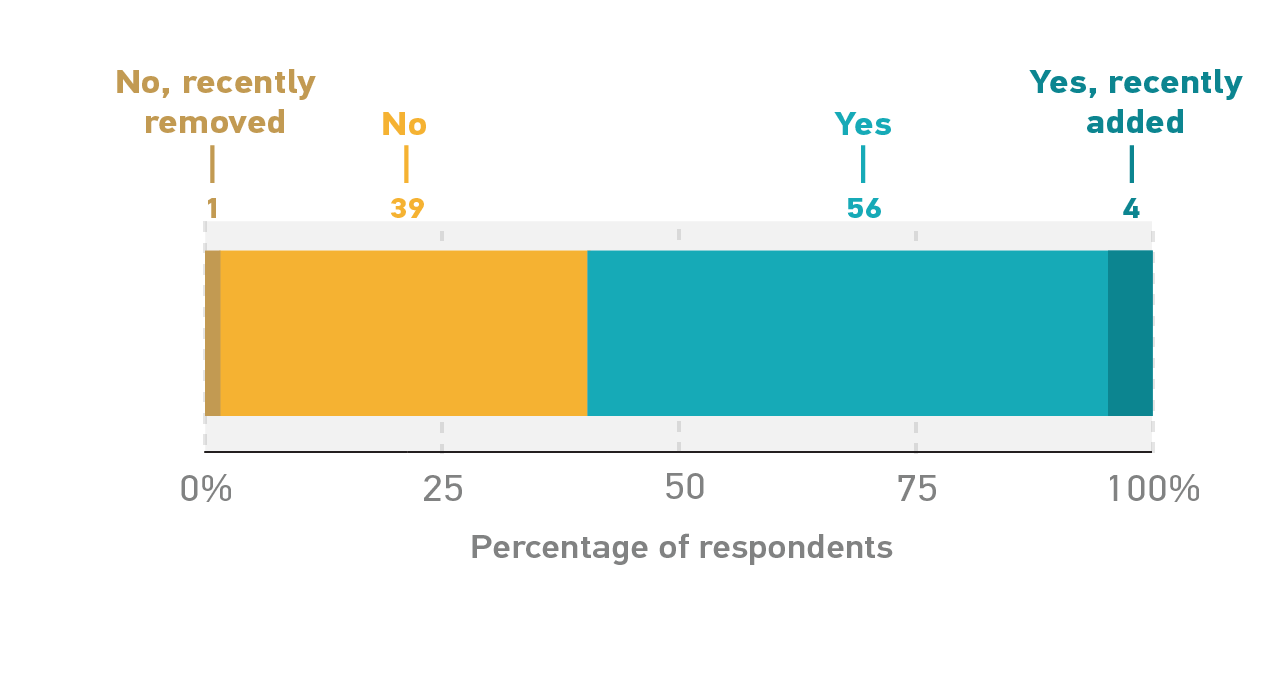

A majority of CIOs have a seat in the president or chancellor’s cabinet. Sixty percent of CIOs surveyed told us that they currently occupy a cabinet position at their institution (see figure 2). The importance of IT leadership holding a cabinet position is well documented—CIOs with cabinet positions spend more time engaged in strategic activities than their counterparts without cabinet appointments.5 Given the increased levels of operational and strategic influence IT has experienced, we might expect there to be a commensurate increase in the number of CIOs added to their respective presidential or chancellorial cabinets. However, president’s and chancellor’s cabinets appear to be largely resistant to the institutional churn brought about by the pandemic: only 4% of respondents reported having been added and only 1% reported having been removed from the cabinet since the beginning of the pandemic, and they all expressed confidence that this change to cabinet membership status would continue post-pandemic.

These results are both promising and concerning. On one hand, we are not observing a significant increase in the number of CIOs holding cabinet positions; indeed, these numbers appear to be fairly stable compared to other data EDUCAUSE has collected on the subject.6 On the other hand, the greater influence of IT in general may suggest that the lack of change in cabinet membership is more the result of institutions being too busy fighting fires to formalize cabinet changes and that perhaps such changes will come later.

The Data: The Role of the CIO

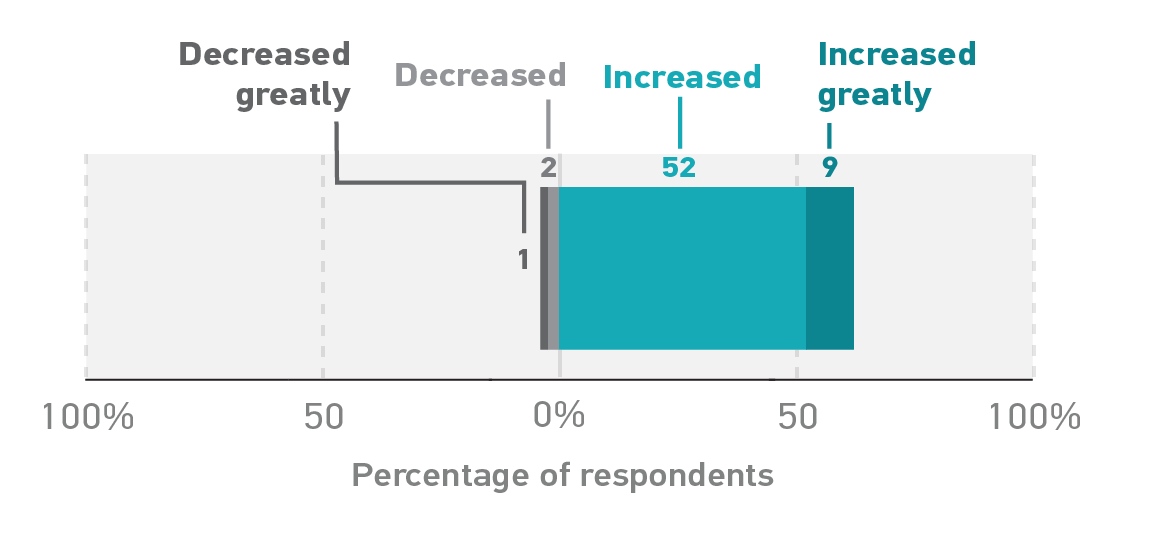

The importance of the role of the CIO has increased since the beginning of the pandemic. Of the 243 IT leaders who responded to our QuickPoll, 149 told us that the importance of the role of the CIO has either increased or increased greatly (see figure 3). And more than two-thirds (71%) of respondents who experienced either increases or decreases in the importance of their roles said they are moderately to very confident that those changes in levels of importance will endure post-pandemic.

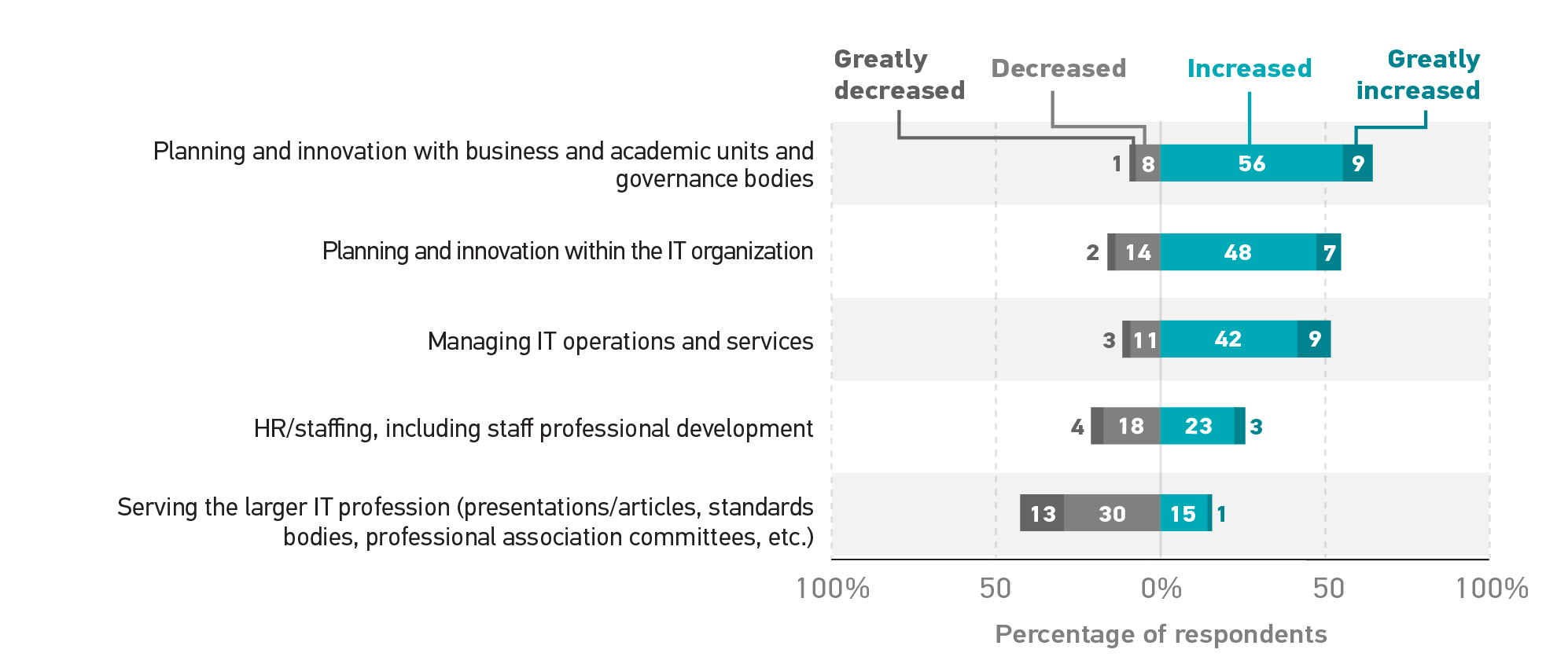

CIOs and IT leaders are spending more time on both operational and strategic activities since the beginning of the pandemic. In The Higher Education IT Workforce, 2019 report, EDUCAUSE research found that the time a typical CIO spends engaged in major activities breaks down as follows:

- Managing IT operations (40%)

- Planning and innovating within the IT organization (20%)

- Planning and innovating with business and academic units and governance bodies (15%)

- HR/staffing, including staff professional development (10%)

- Serving the larger IT profession (presentations/articles, standards bodies, professional association committees, etc.) (5%)

- Other (5%)7

Since the onset of the pandemic, majorities of CIOs told us that they are spending considerably more time on strategic activities, such as planning and innovating with business and academic units and governance bodies (65%), planning and innovating within the IT organization (55%), and managing IT operations and services (51%) (see figure 4). And while increases and decreases in the amount of time CIOs spent on HR and staffing issues are relatively equal, a sizable percentage of CIOs (43%) reported a decrease in the amount of time spent serving the larger IT profession.

CIOs holding cabinet positions are spending a lot more time planning and innovating with partners across campus than their non-cabinet counterparts. Since the onset of the pandemic, the amount of time CIOs with cabinet posts spend planning and innovating with business and academic units and governance bodies has increased significantly more than for CIOs without cabinet positions (72% versus 54%). This stands to reason, given the centrality of IT to identifying, implementing, and supporting technology solutions to a host of pandemic-related problems. Additionally, this difference suggests that CIOs with cabinet seats have been empowered to spend more time working with campus partners than their counterparts without cabinet positions.

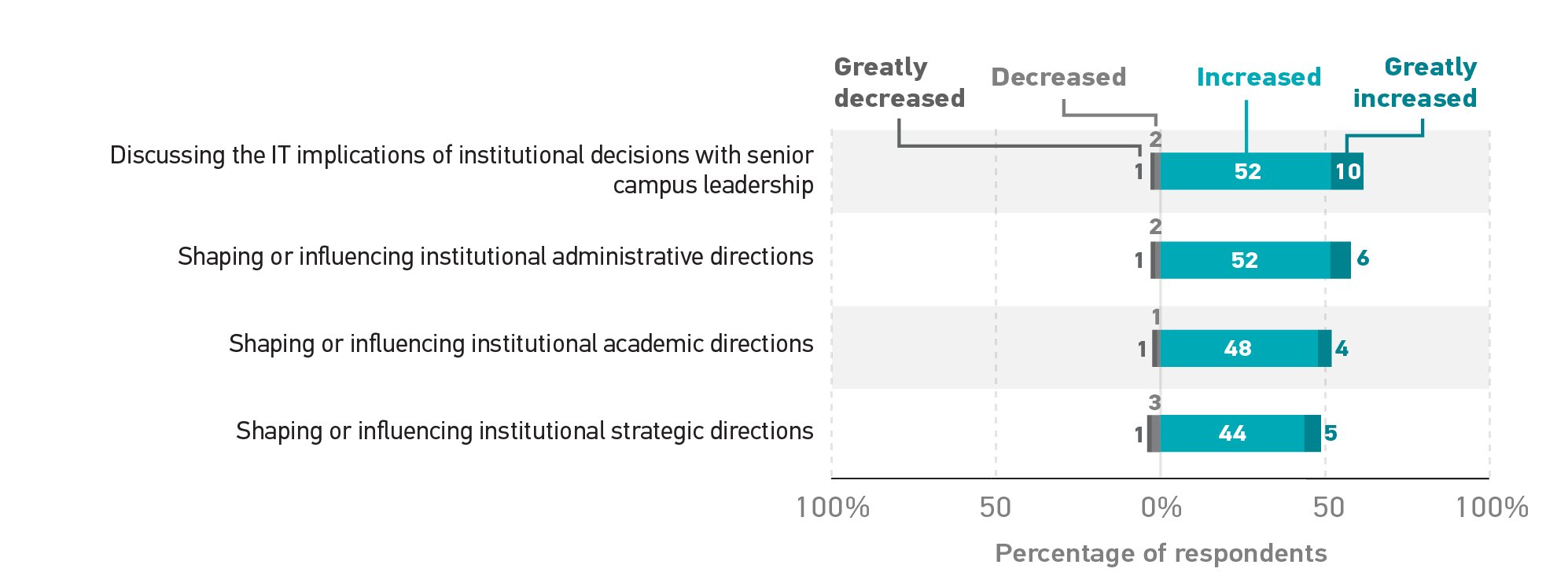

The strategic importance of the role of the CIO is reflected in the work they’ve been doing since the pandemic. A majority of CIOs reported increases since the onset of the pandemic in the importance of their role in discussing the IT implications of institutional decisions with senior leadership (62%) and shaping or influencing institutional administrative directions (58%) and academic directions (52%); nearly half said the same for shaping or influencing institutional strategic directions (49%) (see figure 5). Given that a majority of CIOs were already engaged—often or almost always—in each of these activities,8 our findings suggest both a deepening of the CIOs commitment to these activities and an increased expectation from others that IT can and should have a seat at the table when strategic decisions are being made. The pandemic has clearly elevated the awareness of the need for the CIO to weigh in on anything that technology touches (which, these days, is just about everything).

The Data: The IT Organization

Changes to C-level positions have been rare since the onset of the pandemic. Higher education IT leadership since the beginning of the pandemic has been remarkably stable, with an overwhelming number of positions experiencing no changes in the past seven months or so. Among respondents whose institutions have C-level IT positions, CISOs, CTOs, and CIOs have experienced the most changes, through the addition, the elimination, or the changing (renaming, reconfiguring, or refactoring) of the position. Respondents’ reasons for these changes fall mainly into three categories:

- Financial or budgetary constraints (e.g., positions cut, positions unfilled, searches cancelled);

- Pandemic responses (e.g., reallocation of responsibilities, consolidation of roles/services); and/or

- General changes (e.g., identification of needs, reordering of the service catalog).

Although the pandemic does not appear to have had a significant impact on IT leadership positions, reorganizations planned for the next year may disrupt that pattern.

Table 1. Changes to C-level positions since the beginning of the pandemic

| Position | Position Added | Position Eliminated | Position Changed (e.g., renamed, reconfigured, refactored) | No Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chief information officer (CIO) | 1% | 1% | 7% | 91% |

| Chief information security officer (CISO) | 6% | 1% | 5% | 88% |

| Chief data officer | 3% | 0% | 3% | 94% |

| Chief innovation officer | 4% | 0% | 1% | 94% |

| Digital transformation officer | 0% | 1% | 0% | 99% |

| Chief technology officer (CTO) | 5% | 2% | 3% | 89% |

| Chief privacy officer | 1% | 0% | 2% | 97% |

| Chief analytics officer | 1% | 1% | 4% | 94% |

| Chief digital officer | 5% | 0% | 0% | 95% |

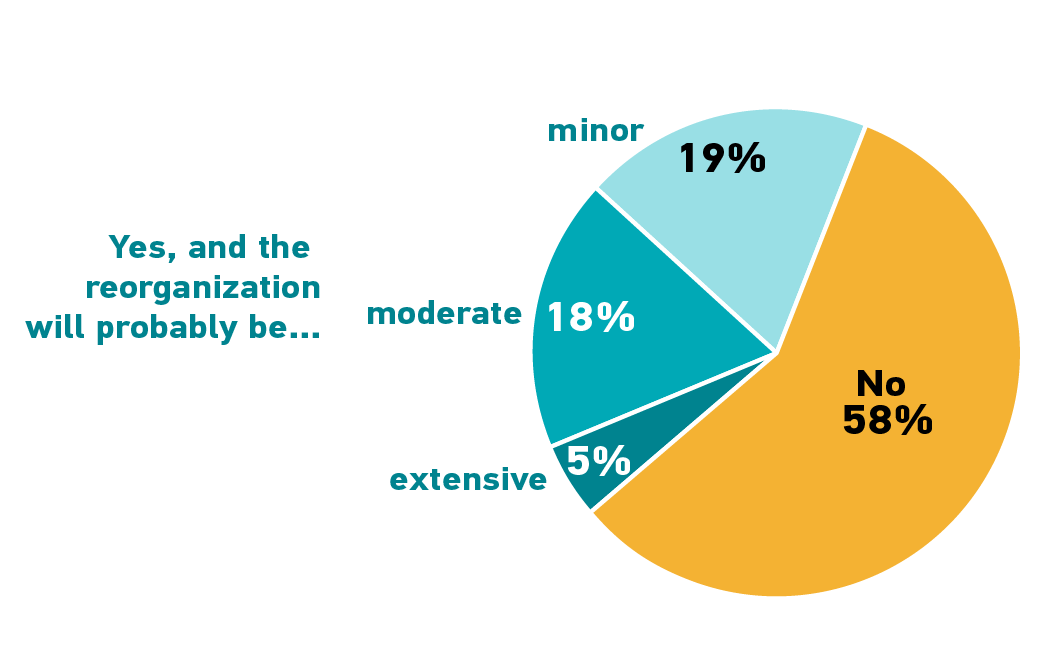

Many IT leaders are planning to reorganize their IT units in the next year. Although a majority of respondents (58%) said their institution has no plans to reorg in the next year, the remainder do, but to varying degrees (see figure 6). When asked to describe the reorganization that is planned and the reasons for it, the responses break into three broad categories: fiscal, functional, and leadership-driven.

Common Challenges

Some IT leaders are skeptical that the rising importance of IT will last, for the usual reasons. Respondents who are less optimistic about the newfound importance of IT leadership continuing post pandemic suggested that changes in institutional leadership, institutional culture, and the temporary nature of the emergency are the main obstacles:

- “Our president will be leaving [...]. All will depend on the next president[…].”

- “Much depends on governance (at this institution).”

- “[C]ultures, organizational behaviors, and processes die hard.”

- “IT and, therefore, the support of the CIO have been clearly needed to meet needs during the pandemic quickly. I have some doubt that engagement will continue once the pressing need goes away.”

- “Although the CIO does not sit on [the] cabinet, they were the lead of the emergency operations center dealing with the pandemic response. Once the emergency operations fade, the CIO’s impact will return to pre-COVID levels.”

Many of the reorganization challenges that respondents identified are well known but bear repeating. Whether the higher ed IT reorgs are prompted by the extraordinary conditions of the pandemic or by the more common changes in institutional and organizational leadership, many of the issues facing senior IT leadership are painfully familiar:

- Identifying cost savings wherever possible

- Reduced budgets requiring that organizations do the same (or more) work with less

- Aligning tactical and strategic delivery of services

- Reducing the higher ed IT workforce (e.g., layoffs, furloughs, retirements, etc.)

- Centralizing IT services

That said, a reorganization in the wake of the pandemic may offer some opportunities for institutions to formalize new relationships and processes that have emerged, to account for new and emergent service needs, and to address other strategic and tactical considerations that may hasten the digital transformation of the institution.

Promising Practices

The pandemic has served as a catalyst for increasing campus influence. For many respondents, the need to respond to the pandemic has created a window of opportunity for IT to demonstrate both its tactical and strategic functions to the entire institution. As respondents told us:

- “IT was the driver to make virtual/remote work possible and has been a key player in COVID reporting and contact tracing solutions; we found ourselves in the SME chair actively working with faculty and staff.”

- “IT has been directly involved in health and safety discussions around pandemic response that we were not previously, and that has reached into more cross-conversation than previously existed.”

- “IT is now seen as more of a strategic investment to enable outcomes and less of a cost of doing business. This has driven a lot of new strategic investments into the organization while protecting us to a degree from the financial impact of COVID.”

- “We were certainly at the forefront of all the solutions needed during the pandemic, so we were involved at every level in every decision and were often the decider because it was all about whether we could provide the service or not and to what level.”

- “I find that I’m now ‘at the table’ for a broader range of strategic discussions that impact the near- and long-term future of the college. I feel significantly more connected to the leadership of the college than prior to the pandemic.”

The elevated importance of CIOs is tied to their ability to demonstrate the value of IT during the pandemic. Most respondents who are confident about the solidification of the importance of the CIO’s role suggest that it is the result of a broad recognition of their ability to deliver and extend IT services while contributing to strategic solutions to institutional crises stemming from the pandemic:

- “There is a greater outward expression around the complexity of the role and our ability to deliver.”

- “We’ve shown the value of IT to all aspects of the institution. We’re seen as a strategic partner and frequently cited as an example of a nimble, forward-thinking organization.”

- “Senior leadership recognizes the role of IT in more areas than they previously had.”

- “The institutional leadership showed their support by trusting me 100% in providing solutions for instructional delivery. With the success that has been shown this fall, I expect my influence to continue to be valued in the future.”

- “Leadership has been extraordinarily important during times of crisis and opportunity, and the CIO position is a great influencer and executor of strategy, tactics, and capabilities, as well as an inspirational leader of people—all necessary to not just survive but thrive during these difficult times of civil, political, economic, and public health unrest.”

The pandemic has thrust IT into the higher education spotlight. Thus far, it seems that IT leadership has capitalized on this opportunity to demonstrate its operational and strategic importance to higher education, to cultivate new relationships across the institution, and to identify new opportunities to innovate and problem solve with institutional partners new and old. Most IT leaders are confident that these new opportunities to demonstrate the value of IT will allow its importance and influence to be felt throughout higher education for years to come.

EDUCAUSE will continue to monitor higher education and technology related issues during the course of the COVID-19 pandemic. For additional resources, please visit the EDUCAUSE COVID-19 web page. All QuickPoll results can be found on the EDUCAUSE QuickPolls web page.

For more information and analysis about higher education IT research and data, please visit the EDUCAUSE Review Data Bytes blog, as well as the EDUCAUSE Center for Analysis and Research.

Notes

- QuickPolls are less formal than EDUCAUSE survey research. They gather data in a single day instead of over several weeks, are distributed by EDUCAUSE staff to relevant EDUCAUSE Community Groups rather than via our enterprise survey infrastructure, and do not enable us to associate responses with specific institutions.↩

- The poll was conducted on October 6, 2020, consisted of 26 questions, and resulted in 278 responses. Poll invitations were sent to participants in EDUCAUSE community groups focused on senior IT leadership. Most respondents represented US institutions, with a handful of respondents representing Canadian institutions. An appropriately diverse and well-balanced range of institution sizes and types participated.↩

- Susan Grajek, “EDUCAUSE QuickPoll Results: IT Budgets, 2020–21,” EDUCAUSE Review, October 2, 2020.↩

- John O’Brien, “Strategic IT: What Got Us Here Won't Get Us There,” EDUCAUSE Review, October 29, 2018.↩

- D. Christopher Brooks and John O’Brien, The Higher Education CIO, 2019, research report, (Louisville, CO: ECAR, August 2019).↩

- For comparative purposes, EDUCAUSE Core Data Service (CDS) data show that 58% of IT leaders sit on the cabinet (July 3, 2019).↩

- Joseph D. Galanek, Dana C. Gierdowski and D. Christopher Brooks, The Higher Education IT Workforce Landscape, 2019, research report (Louisville, CO: EDUCAUSE, February 2019).↩

- Brooks and O’Brien, The Higher Education CIO, 2019, 10.↩

D. Christopher Brooks is Director of Research at EDUCAUSE.

© 2020 D. Christopher Brooks. The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 International License.