Academic librarians increasingly provide guidance to faculty and students for the integration of digital information into the learning experience.

Librarians in educational settings try to provide not only physical access but also intellectual access to recorded information. Because digital resources constitute a significant portion of this information, librarians need to pay explicit attention to the effective retrieval and use of these assets. More specifically, users should have the ability to understand both the information itself and the medium through which it is conveyed. These competencies are known collectively as information and communication technology (ICT) literacy.

Many librarians have shied away from ICT literacy, concerned that they may be asked how to format a digital document or show students how to create a formula in a spreadsheet. These technical skills focus more on a specific tool than on the underlying nature of information. Nevertheless, librarians know that the medium impacts how information is communicated and experienced. It is that aspect of technology that librarians can address as they extend their work with instructors, especially for technology-enhanced instruction.

Academic librarians increasingly play an instructional role in students' scholarly lives. Traditionally this instruction has consisted of just-in-time reference desk help and one-shot presentations, often to demonstrate the use of databases. In this model of instruction, the link between the librarian and the course instructor consists of the students themselves, who are usually self-motivated to ask for help.

More recently, however, librarians have begun to use an embedded model as a way to deepen their connection with instructors and offer more systematic collection development and instruction. That is, librarians focus more on their partnerships with course instructors than on a separate library entity. Through such partnerships, the integration of ICT literacy can be tracked from the process of course development to the assessment of students' final projects.

Introducing the TPACK Model

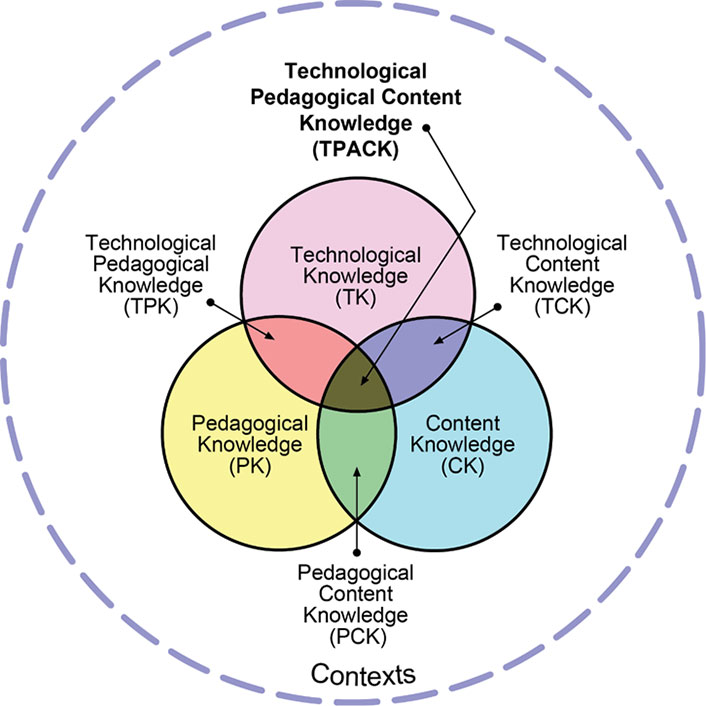

One model that captures the idea of expertise needed by academic librarians is TPACK: Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge. This model shows the kinds of knowledge needed for instruction in the Digital Age (see figure 1). Although one might think that the course instructor should possess all these knowledge bases, that isn't always the case. If TPACK is applied to instruction within a course, theoretically several people could be contributing this knowledge to the course. A good exercise is for librarians to map their knowledge onto TPACK.

ICT reflects the learner side of a course. However, ICT literacy can be difficult to integrate because it does not constitute a core element of any academic domain. Computer science courses usually cover ICT literacy from a technical or mechanical perspective (such as the information communication channel) rather than from an information-centric approach. Whereas many academic disciplines deal with key resources in their field, such as vocabulary, critical thinking, and research methodologies, they tend not to address issues of information seeking or collaboration strategies, let alone technological tools for organizing and managing information.

Collaborating with Instructional Designers

Instructional design for online education provides an optimal opportunity for librarians to fully collaborate with instructors. A program develops courses to address needs such as closing programmatic gaps, integrating new concepts and trends in the discipline's profession, engaging student interest, or meeting demands from the institution or accreditation bodies. The course's goals and desired learning outcomes can then be determined by the program faculty. The outcomes can include identifying the level of ICT literacy needed to achieve those learning outcomes, a task that typically requires collaboration between the librarian and the program's faculty member. Librarians can also help faculty identify appropriate resources that students need to build their knowledge and skills. As education administrators encourage faculty to use open educational resources (OERs) to save students money, librarians can facilitate locating and evaluating relevant resources. These OERs not only include digital textbooks but also learning objects such as simulations, case studies, tutorials, and videos.

This is the point where ICT literacy really comes into play. Reading online text differs from reading print both physically and cognitively. For example, students scroll down rather than turn online pages. And online text often includes hyperlinks, which can lead to deeper coverage—as well as distraction or loss of continuity of thought. Also, most online text does not allow for marginalia that can help students reflect on the content. Teachers and students often do not realize that these differences can impact learning and retention. To address this issue, librarians can suggest resources to include in the course that provide guidance on reading online.

Similarly, other types of media need to be evaluated, comprehended, and interpreted in light of their critical features or "grammar." For example, camera angles can suggest a person's status (as in looking up to someone), music can set the metaphorical tone of a movie, and color choices can be associated with specific genres (e.g., pastels for romances or children's literature, dark hues for thrillers). Librarians can explain these media literacy concepts to students (and even faculty) or at least suggest including resources that describe these features in the course to deepen students' interactions with these types of media. The emphasis should be on the nature of information and how it is expressed.

Bringing Tech Specialists Into the Fold

Instructors might also consider incorporating technology into students' demonstrations of competency, such as making podcasts, videos, and infographics. However, instructors need to make sure that students have the technical skills to produce these products. Although librarians might understand how media impacts the representation of knowledge, they aren't necessarily technology specialists. However, instructors and librarians can collaborate with technology specialists to provide that expertise. In many institutions, librarians provide online tutorials and face-to-face workshops for the academic community. While librarians can locate online resources—general ones such as Lynda.com or tool-specific guidance—technology specialists can quickly identify digital resources that teach technical skills.

Similarly, both instructors and librarians can leverage the expertise of instructional designers to help package information through source knowledge and supporting documents, learning activities, and assessments. Many instructors and librarians have not had formal courses on instructional design, so collaborations can provide an authentic means to gain competency in this process.

Now, let's bring the TPACK model back into the course. Instructors likely have high content knowledge (CK) and satisfactory technological content knowledge (TCK) and technological knowledge (TK) for personal use. But even though newer instructors acquire pedagogical knowledge (PK), pedagogical content knowledge (PCK), and technological pedagogical knowledge (TPK) early in their careers, veteran instructors may not have received this training. The same limitations can apply to librarians, but technology has become more central in their professional lives. Librarians usually have strong one-to-one instruction skills (an aspect of PK), but until recently they were less likely to have instructional design knowledge. ICT literacy constitutes part of their CK, at least for newly minted professionals. Instructional designers are strong in TK, PK, and TPK, and the level of their CK (and TCK and TPK) will depend on their academic background. And technology specialists have the corner on TK and TCK (and hopefully TPK if they are working in educational settings), but they may not have deep knowledge about ICT literacy.

Therefore, an ideal team for ICT literacy integration consists of the instructor, the librarian, the instructional designer, and the technology specialist. Each member can contribute expertise and cross-train the teammates. Eventually, the instructor can carry the load of ICT literacy, with the benefit of specific just-in-time support from the librarian and instructional designer.

Librarians should seriously consider TPACK as a way to embed themselves into the classroom to incorporate information and ICT literacy. Because TPACK is a recent model, many instructors might not know about it, so librarians can facilitate professional development in this area as well. At the same time, librarians can point out their own knowledge—linking it to ICT literacy. In the process, not only will students become more ICT literate, which is the ultimate goal, but librarians can build a stronger partnership that contributes to student learning as a whole.

This post is part of the 2019 ELI Key Issues series, which focuses on the top five teaching and learning issues as cited in the EDUCAUSE Learning Initiative's recent community survey.

Lesley S. J. Farmer is professor of library media at California State University Long Beach.

© 2019 Lesley S. J. Farmer. The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 International License.