By emphasizing interpersonal connection in the design process, instructional designers can foster stronger relationships among students and faculty in digital learning environments.

As at many colleges and universities across the nation, the teaching and learning landscape at William & Mary, a midsized liberal arts institution, is rapidly evolving. Online and hybrid programs are being woven throughout the William & Mary experience at such a fast pace that we have had to stop and ask ourselves what exactly we want that experience to be.

As a continuation of our work on a contextualized approach to the digital learning environment, William & Mary's University eLearning Initiatives [https://www.wm.edu/offices/apel/] created a new model of faculty development for online course design. The model deliberately cultivates human-centered digital learning by emphasizing connection, which we know to be difficult to foster within digital environments without intentional design. The importance of human connection has been reaffirmed through new university president Katherine Rowe's Thinking Forward campaign, from which the theme "cultivating connections" emerged as a hallmark of the William & Mary experience. We also know from the cognitive sciences that learning is fundamentally social and that social relationships activate neural pathways.

The Human-Centered Student Experience

A human-centered approach to instructional design takes into account the relationships we hope faculty will cultivate with their students online, as well as the relationships we cultivate with instructors as we teach them about online pedagogy. In our online courses, we strive to cultivate faculty-student and student-student relationships that are similarly dynamic as those for which our brick and mortar courses are well known. We know that in a digital context, these relationships require intentional design and implementation to be achieved. As such, we have outlined a list of attributes of effective online instruction that research demonstrates can nurture these relationships and interweave them throughout our hybrid faculty development modules. These include social presence, instructor presence, community building, and respect for students as partners in the learning process.

The Human-Centered Instructor Experience

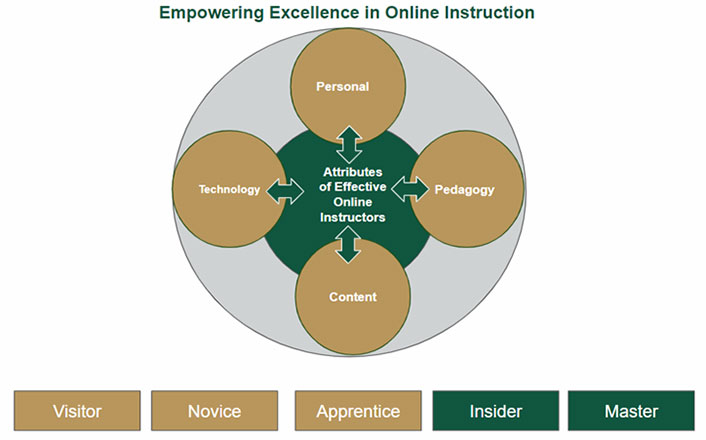

Throughout our faculty development seminar, we emphasize getting to know instructors as individual learners, and we seek to develop self-efficacy in their ability to teach online. We contextually situate our approach using the four domains highlighted by Palloff and Pratt as key components of faculty development for online teaching: personal, pedagogy, content, and technology. Leveraging our understanding of instructors and their individual relationships to pedagogy, content, and technology helps us more adeptly assess implications for instructional practice. We begin this process of understanding through an intake interview in which we become familiar with instructors, their content, and their beliefs about knowledge construction and teaching practices.

Our team then considers the level of online experience an instructor brings to the table. This helps establish the instructor's perceived comfort level with using digital tools, as well as which technological and pedagogical skills they may need to further develop. Individuals may reside in any one of the five phases of online faculty development, as outlined by Palloff and Pratt:

- Visitor: occasionally uses digital tools in face-to-face courses

- Novice: consistently uses digital tools to enhance face-to-face courses

- Apprentice: has taught online for one or two terms

- Insider: has taught more than two semesters online

- Master: has taught online for multiple terms and designed several online courses

Faculty development for online learning is both an individual and iterative process where one-size-fits-all approaches aren't likely to work. We don't expect mastery in an instructor's first year teaching a course, nor do we impose novice content and training upon faculty who have progressed to another phase in development (see figure 1).

In addition to considering faculty experience, we rely heavily on adult learning theory throughout our design process to drive many of our instructional decisions for development modules. When planning faculty development experiences, we take into account the following major principles:

- Adults learn by building new knowledge upon a foundation of previous knowledge and experience, learning best when their experience is acknowledged.

- Adults prefer active over passive learning and are most satisfied when they are able to directly apply what they are learning.

- Adults value autonomy and self-directed learning.

- Adults aren't likely to fully participate in learning experiences that are not meaningful to them.

How does this translate to faculty development for online instructors? We honor the unique experience of each person by offering individual choice in learning content as well as one-on-one support. Additionally, we use cycles of learn, do, reflect so that faculty first have the opportunity to acquire new content and skills within a hybrid environment; then can try to apply them in our face-to-face sessions; and finally reflect in order to further direct their own learning.

Faculty Development in Situ: ReVISION Bootcamp 2019

Our ReVISION Bootcamp is aimed at revising current online/hybrid offerings and is geared toward instructors in the apprentice, insider, and mastery phases of faculty development. This means they have taught at least one online course with us the previous summer. This year, we began the week by asking faculty to reflect on their online courses from the previous summer, specifically considering the following:

- What about the course worked well? Which of those things would you want to maintain throughout this next iteration?

- How might the course be improved? Are there elements that frustrated you or that you noticed could have worked better for your students?

- What are some ways in which you can "level-up" your course to make it even more engaging, effective, rigorous, etc.?

From this reflection, we asked instructors to create a 50-word "vision statement" to serve as an impetus for driving the changes they hoped to make to their courses heading into summer 2019. We then presented instructors with the Quality Matters assessments for their courses, a rubric our team uses to ensure high standards for online courses. Using the newly created vision statement alongside the QM review that we had already discussed with instructors, we then asked faculty to articulate and prioritize six to nine attainable goals they thought they could achieve within the three-day bootcamp.

Learn

Using these goals as guideposts, we directed faculty members to brief instructional videos we created for the bootcamp based on the most common concerns observed from our online course assessments and asked individual instructors to choose which modules of instruction they found most beneficial to help achieve their workshop goals. Videos covered topics including course organization, articulating alignment of learning objectives, and simple accessibility strategies such as captioning and including alt text.

Do

As instructors learned from the modules they chose and revised their courses in face-to-face workshop sessions, we were available to help in a variety of capacities, whether that meant assisting with alignment of course objectives to module objectives, offering suggestions for creating a greater sense of presence in the course, creating captions for accessible videos, or recording new instructional content in the studio.

Reflect

Before lunch and at the end of each day, instructors reflected on their goals and achievements, setting new goals for the following day. They also had the opportunity to engage in a peer feedback protocol, where they navigated a colleague's course in order to offer suggestions and/or congenially steal ideas.

This structure afforded us the ability to meet the instructors' needs with various levels of experience while connecting them to colleagues, resources, and support to achieve their goals. In this way, we centered the learning experience around the individual rather than the group, maximizing our interactions and the growth of each faculty member throughout the bootcamp.

This post is part of the 2019 ELI Key Issues series, which focuses on the top five teaching and learning issues as cited in the EDUCAUSE Learning Initiative's recent community survey.

Katalin Wargo is an Instructional Design Manager at University eLearning Initiatives and a doctoral student in the School of Education at William & Mary.

© 2019 Katalin Wargo. The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY 4.0 International License.