This series will explore concepts, practices, and organizational shifts that are central to inclusive pedagogy in higher education.

Before you read further, we'd like you to consider how you define inclusion. What does it mean to you? Please enter a brief (three to five words or up to forty characters) definition of inclusion into the Answer Garden text field below and click Submit to view a word cloud with other responses.

We asked you to share your definition of inclusion because, if you are reading this post, it is likely that you are in some way connected to a community with a vested interest in teaching and learning, and you value student experience, persistence, retention, and satisfaction. The responses collected from you, our teaching and learning community, will inform the discussion in our next post about what inclusion might look like in practice. Compositionist Claire Lauer explained that definitions are important to a community because they represent "the collective interests and values of the community for which the definition matters."1 Especially when our community values placing students at the center of the educational experience, the terms we use to think, talk, and collaborate matter.

This initial post defines three important terms—disclosure, accessibility, and inclusion—in the hope of contributing to a common vocabulary in our community around accessible and inclusive teaching and learning. These terms are a starting point for a larger conversation and a shift in design practices.

Attempting to define nuanced concepts brings with it a risk or reductionism, which is why the definitions that follow draw from cognitive science, universal design, and disability studies.

Disclosure or Self-Identity

Have you heard of the WYSIATI principle? Coined by Nobel Prize laureate Daniel Kahneman and pronounced "whiz-ee-yaht-tee," this acronym stands for What You See Is All There Is. It's theorized as a common, unconscious bias that even well-intentioned educators make: "I can't see it, so it doesn't exist." It's the idea that our minds are prone to making judgements and forming impressions based on the information available to us. In teaching and learning, the WYSIATI principle is an idea with consequences. That is, the students in our classes have all kinds of invisible circumstances that can impact their learning. Some of these circumstances include the following:

- Attention or comprehension problems because of an emotional hardship or learning disability

- Using a single device, like a phone or a tablet, for doing all of their digital coursework

- Familial or other work obligations outside of school

- A long commute to and from campus

- Homelessness, or food or housing insecurities

- Low vision, but not blindness; difficulty looking at a screen for extended periods of time

- Difficulty hearing, but not deafness

- A lack of experience or experienced mentors in higher education or in particular disciplines

- Returning to school after a period of time and feeling rusty, insecure, or experiencing imposter syndrome2

While campuses are required to provide services (e.g., alternative formats for course materials, extra exam time, etc.) for students with disabilities and may have additional support for students with various other challenges, unless students self-identify or disclose their circumstances, courses and associated materials may contain barriers to student learning—even if those barriers are inadvertent. A faculty colleague shared with us that she had favored the use of a particular color to emphasize important ideas in her documents for nearly an entire semester before a student revealed to her that he could not see that color. Had she known, she would have made a simple change so that the student could read or understand the most important parts of the course documents. This is the WYSIATI principle at work: this faculty member couldn't see that her student was color blind, so she didn't know that she needed to do anything about it.

Whether or not students need to self-identify or disclose their circumstances is not the point. The point is that invisible circumstances exist regardless of disclosure, and, collectively, we can all do a better job of awareness: identifying and removing barriers from courses can benefit everyone, but doing so can also be critical to those who need it.

Accessibility

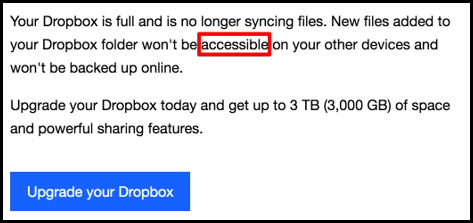

Colloquially, the term accessibility is often used to describe items or spaces that are available for use. One can expect an accessible road to be open as an option for safe, unobstructed travel for most vehicles. Here's another example of an email from Dropbox, an online file storage tool, after a user reached the free storage limit.

In this email, the term accessible refers to availability. The user will not be able to access files because they will not be available on other devices. In both of these examples, however, the term accessible is limited to able individuals—those who are able to access material in its current form. In teaching and learning, as well as in universal design, accessible means that materials and spaces are not only available but also free from invisible barriers—even unintended ones—for anyone who needs to access those materials.

For example, an accessible text is one that is clearly organized, uses an unembellished font, and incorporates headings to separate sections. Online images should contain alternative text for moments when pages don't load properly or for readers who use assistive devices. Videos should include closed captions or transcripts for people with hearing issues or attention/tracking problems, as well as for those who multitask (watch while exercising, for example). Even certain colloquial terms and cultural references that are used without context or explanation in a lecture or course material can function as barriers to learning.

The term accessible is evolving and currently connotes disability services and accommodations. Citing a keynote address by Andrew Lessman, a distance education lawyer, Thomas Tobin and Kirsten Behling explain why accessibility as accommodation is a problematic way to think about design: "'accommodations are supposed to be for extraordinary circumstances'" and, paraphrasing him, added the following:

[I]t should be very rare for people to need to make specific requests for circumstances to be altered just for them [. . .] all of these environments, whether physical or virtual, should be designed so that the broadest segment of the general population will be able to interact successfully with materials and people.3

This idea applies to course design and instruction just as much as it applies to physical spaces. Practicing accessible course design and instruction is an opportunity (and a necessary imperative) to develop a pedagogy of inclusion.

Inclusion

The previous two definitions have tried to articulate the idea that students carry intersecting invisible circumstances with them into the classroom. Whether or not students disclose their circumstances—or whether faculty members invite students to disclose them—does not determine their existence. From this perspective, inclusion means designing and teaching for variability. Faculty can practice inclusive pedagogy by following universal design principles and offering multiple options for representation, engagement, and expression:

Options are essential to learning, because no single way of presenting information, no single way of responding to information, and no single way of engaging students will work across the diversity of students that populate our classrooms. Alternatives reduce barriers to learning for students with disabilities while enhancing learning opportunities for everyone.4

In a Nutshell . . .

Inclusive pedagogy can be an act of intention—something that is initiated before and during the course design process—rather than being an act of revision or omission.

Contribute to the Conversation!

Tweet your favorite inclusive design practices and resources, and be sure to tag @TLIatCI, @a11ygal, and @lgonzalez1

For more insights about advancing teaching and learning through IT innovation, please visit the EDUCAUSE Review Transforming Higher Ed blog as well as the EDUCAUSE Learning Initiative page.

Notes

Special thanks to Amanda Timpson, Sarah Lohnes Watulak, and Tara Hughes for contributing their time to this post.

- Clair Lauer, "Contending with Terms: 'Multimodal' and 'Multimedia' in the Academic and Public Spheres," Computers and Composition 26, no. 4 (2009): 225–239. ↩

- Valerie Young, "Finding a Name for the Feelings," Imposter Syndrome (website), October 23, 2017; Megan Dalla-Camina, "The Reality of Imposter Syndrome," Psychology Today, September 23, 2018. ↩

- Thomas Tobin and Kirsten Behling, Reach Everyone, Teach Everyone: Universal Design for Learning in Higher Education (Morgantown: West Virginia University Press, 2018). ↩

- Ibid. ↩

Lorna Gonzalez is an Instructional Designer for Teaching and Learning Innovations and a Lecturer at California State University Channel Islands.

Kristi O'Neil is the Instructional Technologist-Accessibility Lead for Teaching and Learning Innovations at California State University Channel Islands.

© 2019 Lorna Gonzalez and Kristi O'Neil. The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY 4.0 International License.