Community college students' learning environment preferences are shaped by circumstances related to gender, work, and family.

Students who attend community colleges are juggling a lot in their lives. More two-year and AA1 students work full time, are married or in a domestic partnership, have children, and are financially independent than are their peers at four-year schools.2 With so many responsibilities on top of the work of being a student, many community college students today may feel like they need superhero-sized endurance to manage it all.

In the ECAR Study of Community College Students and Information Technology, 2019, the EDUCAUSE Center for Analysis and Research examined topics related to the technology experiences of community college students, including their learning environment preferences. While about half of our sample reported that they prefer blended environments, some two-year and AA students told us they favor courses that met mostly or completely online. So, who are these students, and what could be influencing their preferences for environments that are heavily or fully online?

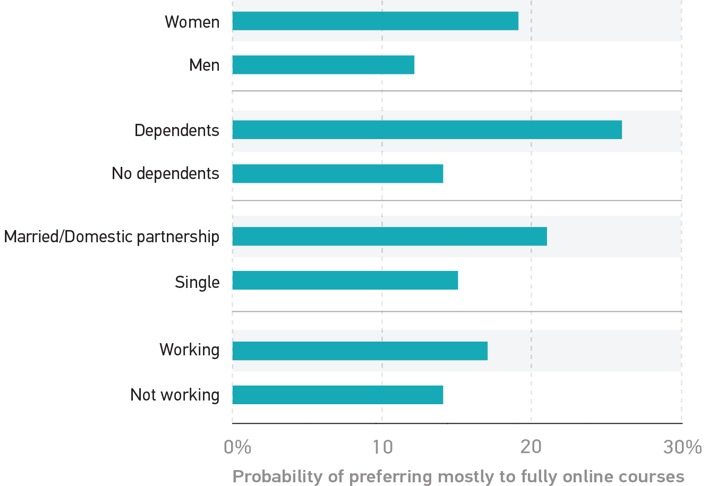

To answer this question, we developed a statistical model that looked at the impact of four demographic variables that are significantly correlated to learning environment preferences: gender, whether or not a student has dependents, marital/relationship status, and employment status. In the logistic regression model, each of these independent variables was a significant predictor of preferences for mostly to fully online courses.3 Based on the results of the model, we generated probabilities that students would prefer mostly to fully online courses for every possible combination of demographic predictors (see figure 1).

We found that women, students with dependents, students who are married or in a domestic partnership, and those who work are significantly more likely to prefer mostly to fully online courses than do their counterparts. Students with dependents are nearly twice as likely to prefer mostly to fully online courses, while women and students who are married or in domestic partnerships are about 1.5 times more likely to have the same preferences.

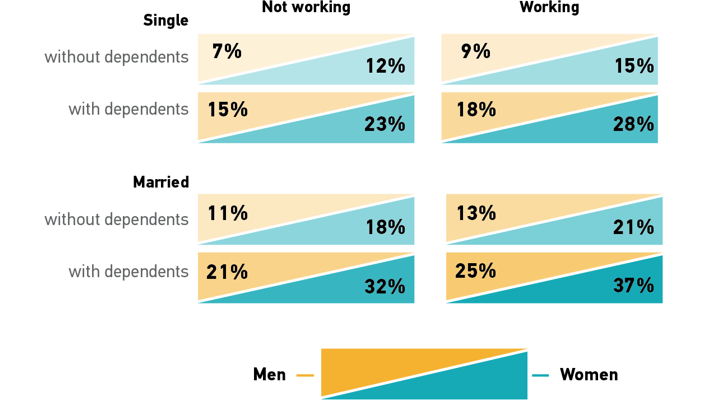

The results for these individual variables provide insight into how one particular factor—like gender or marital status—is related to a student's learning environment preferences. However, the lives of students are not defined by a single variable but are considerably more complex. That is, the specific combinations of any of these demographic factors are likely to reveal the more nuanced ways student preferences for online environments are based on their lived experiences. To provide a comprehensive picture of how gender, dependents, marital/relationship status, and employment status relate to learning environment preference, we generated 16 probabilities, or one probability for each of the possible combinations of the four independent variables that were found to significantly predict learning environment preferences (see figure 2).

When all four key demographic factors were considered, we found that those who are most likely to prefer primarily to completely online courses are married, working women with dependents. The group that was second most likely to prefer online learning environments is married women who have dependents and who do not work, followed closely by single, working women with dependents. While the female students in our study could be caring for parents, siblings, or other family members, studies suggest that these dependents are far more likely to be the children of these students. In fact, students with dependent children represent 30% of the total community college student population,4 and single mothers are growing as a share of the overall college population.5

Married, working mothers may prefer mostly to fully online courses because they must simultaneously balance the pressures of going to school and having a job and a family. Research has shown that the practical conveniences of online courses often drive learning environment preferences for community college students6 and that these online learning environments are often chosen for practical reasons versus the belief that students will learn more than they would in a face-to-face course.7 And married, stay-at-home mothers may favor online learning environments for similar reasons.

Although women who are married or in domestic relationships have partners to help with at-home responsibilities, national statistics show that women still shoulder more of the household work and spend more time providing primary care to children than men.8 Single, working mothers may also prefer online environments out of sheer necessity, as they must manage the demands of employment, coursework, and caring for children—all without the support of an at-home partner. In the absence of the ability to teleport, time travel, or clone themselves, courses that are primarily or completely online offer the flexibility that many mothers critically need, as these online learning environments allow them to work toward their degree or certificate whenever or wherever they are able without (or with fewer) interruptions to their work and home schedules.

Single men with no dependents (whether or not they are employed) prefer online learning environments less than women do. The groups that our model predicted to have the next lowest preferences for online learning are married, unemployed men with no dependents; single, unemployed women with no dependents; and married, working men with no dependents. The responsibilities of family life (especially with children) are factors that shift the preferences of community college learners from mostly face-to-face learning environments to mostly online ones.

To help improve the learning outcomes of students with dependent children, higher education IT units should consider leveraging analytics to better understand the needs of these students and identify potentially effective solutions. Offering students the opportunity to voluntarily share information about their dependents (such as the dependents' ages, the number of hours students spend each day or week caring for their dependents, and the financial responsibility associated with dependent care) in student service portals can provide institutions with deeper insights into the lives of this population.9 These additional data points can help institutions make decisions about the types of courses that best meet students' needs, track students' progress, and identify the kinds of resources that can be offered to support parents. Educating students about their learning environment options through orientation and training also arms them with information that can help them choose course environments that work best for them. Online student success tools such as self-service referral systems to campus and community resources (e.g., family and women's centers, counseling services, and childcare services) can be leveraged to share information with parents. IT units, faculty, and staff can also advocate for increasing access to affordable, quality childcare and other campus services that serve the parents of children who are working hard, stretching themselves thin, and doing whatever it takes to make a better life for themselves and their families.

Thanks to Kate Roesch, data visualization specialist for the EDUCAUSE Center for Analysis and Research, for her vision in creating the figures for these data.

For more information and analysis about higher education IT research and data, please visit the EDUCAUSE Review Data Bytes blog as well as the EDUCAUSE Center for Analysis and Research.

Notes

- Community colleges were defined as institutions that (1) have the Carnegie class of AA, and (2) are two-year institutions. In this study, two institutions met one or the other, but not both, of those criteria, but were included after verifying their community college status. ↩

- Dana C. Gierdowski, ECAR Study of Community College Students and Information Technology, research report (Louisville, CO: ECAR, May 2019). ↩

- The significance levels for each variable are as follows: gender (p < .001); dependents (p < .001); married (p < .001); and working (p < .01). ↩

- Elizabeth Noll, Lindsey Reichlin, and Barbara Gault, College Students With Children: National and Regional Profiles, research report (Washington, DC: Institute for Women's Policy Research, January 2017). ↩

- Melanie Kruvelis, Lindsey Reichlin Cruz, and Barbara Gault, "Single Mothers in College: Growing Enrollment, Financial Challenges, and the Benefits of Attainment," briefing paper (Washington, DC: Institute for Women's Policy Research, September 2017). ↩

- Shanna Smith Jaggars and Di Xu, Online Learning in the Virginia Community College System, research report (New York: Community College Research Center, September 2010). ↩

- Not Sold Yet: What Employers and Community College Students Think About Online Education, research report, (New York: Public Agenda, September 2013). ↩

- US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, "American Time Use Survey — 2018 Results," press release, June 28, 2018. ↩

- Larissa M. Mercado-López, "How Faculty Can Help Student Parents Succeed," Inside Higher Ed, November 30, 2018. ↩

Dana C. Gierdowski is a Researcher at EDUCAUSE.

D. Christopher Brooks is Director of Research at EDUCAUSE.

© 2019 Dana C. Gierdowski and D. Christopher Brooks. The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 International License.