Mixed reality tools are expected to fundamentally change how we interact with the physical world and our growing assortment of digital worlds, how we communicate with each other, and how we teach and learn.

Much has been made of the potential for immersive technology to revolutionize teaching and learning. Often placed under the banner of XR (extended or cross reality), these tools are expected to fundamentally change how we interact with the physical world and our growing assortment of digital worlds, how we communicate with each other, and, of course, how we teach and learn. But are the XR tools available today worth the cost?

I believe the answer is a resounding "yes." Despite the initial price tags and the time required to learn how to use and support them effectively, several digital humanities (DH) projects at Bates College over the past two years demonstrate that these tools are much more than distracting toys. This post examines these projects and their impacts on student learning. They can be placed in two categories: historical reconstructions and collaborative world building.

Historical Reconstructions

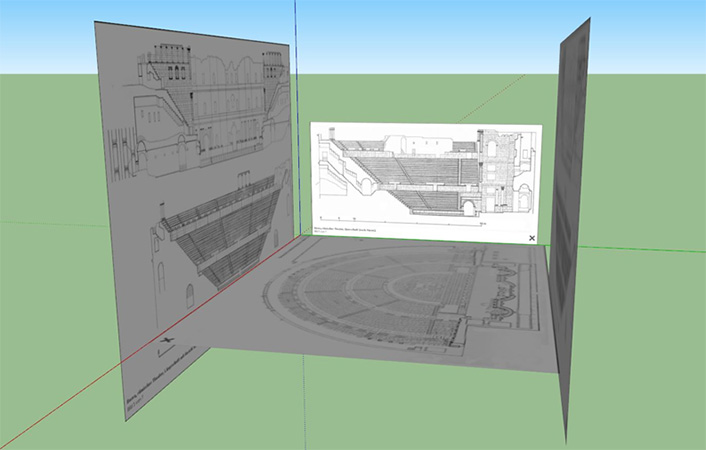

Within the past few years, a number of faculty in the humanities at Bates have begun to incorporate 3D modeling in their courses. Inspired by the work of Matthew Nicholls of the University of Reading and his Virtual Rome [https://www.reading.ac.uk/classics/Stories/class-matthew-nicholls-story.aspx] project, these faculty have designed projects in which students use SketchUp Pro to digitally reconstruct historical structures, such as ancient mosques and Roman theatres; where possible, images are used to help guide the reconstruction process (see figure 1).

Figure 1. The beginning of a 3D model of a Roman theatre

Students in these Bates courses are learning how to engage both critically and creatively with course materials by constructing digital models, justifying their design decisions, and learning some practical 3D modeling skills along the way. Emphasis is placed on the limitations and ethics involved in the reconstruction process, particularly because designers often have to make choices about what a structure or feature looked like when we may have little or no illustrative or descriptive evidence available.

Faculty in these courses reported that most students found the 3D modeling work engaging, even "the highlight of the semester." Despite no prior training, most students were able to produce high-quality work over the course of a few weeks when accompanied by hands-on training and support provided by academic technologists. Additionally, while the 3D modeling process helped students gain a deeper appreciation of the structures themselves, the incorporation of virtual reality (VR) helped them understand what it might have been like to actually be in these places (see figure 2).

Figure 2. View from inside a Roman theatre reconstructed by an individual student

VR tools provide students with the opportunity to immerse themselves in their reconstructions, offering unique perspectives on how these structures may have impacted the lived experiences of the people who resided in these ancient cities.

Using Oculus Rift headsets and the software Kubity, students were able to load their SketchUp models in a VR environment within minutes, making it easier to embed the technology in smaller classes or make it available in labs outside class time. For example, in one class on Latin poetry, students were able to tour several Roman theaters in VR, which informed class discussions about what it might have been like to experience the recitation of Seneca's poetry firsthand.

Collaborative World Building

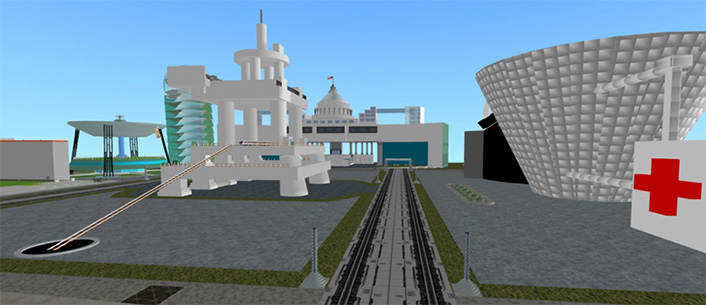

Another example comes from an English course in which a similar suite of XR tools was used to help students explore the course themes of world building and radical collaboration. In this project, students worked together to create an entire fictional city that users could experience in an immersive VR format. Students worked as a class to design the city and describe its culture (see figure 3). We then provided SketchUp training, and they broke into pairs to create the components.

Figure 3. Part of a virtual city built by an English class at Bates College

Once the components were completed, we helped students collate them into a single model that could be loaded into Kubity for VR integration. The resulting VR simulation was then made available to the entire Bates community during an open house featuring scholarly work by students; by combining VR headsets with projectors or displays, others can see what is being viewed (see figure 4).

Figure 4. Virtual world on display at the Mount David Summit at Bates College

According to the instructor, Tiffany Salter, the project increased student investment in the course; students were thrilled with the end product and very proud of what they were able to produce together.

In addition to new creative design skills, these students gained an appreciation for the importance of collaboration and how it can enable them to produce something far grander than they would have been able to do alone. Moreover, the incorporation of XR technology into somewhat nontraditional settings may have helped change the way students feel about their use of these tools. By the end of this project, students saw the value of using this technology, not as an end in itself but as a means to both expand and accomplish their goals.

Closing Thoughts

Through projects like these, XR technologies can work in the classroom in ways that enrich the educational experience and provide both students and instructors with new ways of realizing learning goals and engaging with course materials.

Importantly, while aims of these projects differed, they all shared two important design features: XR tools were selected based on their ability to support core learning objectives for the course, and the implementation plan was developed in partnership with content experts and academic technologists who provided ongoing access to the tools and hands-on support. In our experience, both of these are key to making XR work in higher education classrooms.

Stay tuned for the next post in this series, where my colleague Cori Hoover and I will discuss an ongoing undergraduate research project, Digital Dura, designed to include students as designers and co-creators of a large-scale historical reconstruction of an ancient Roman city, Dura-Europos.

Interested in learning more? Consider joining the new EDUCAUSE XR Constituent Group.

Kai Evenson is Senior Academic Technology Consultant and Manager of the Imaging and Computing Center at Bates College.

© 2018 Kai Evenson. The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 International License.