Instructional designers at CU Boulder researched the student experience in large lectures and used their findings to develop recommendations to improve campus-wide practices concerning large lecture courses.

Large lecture courses are a staple of the undergraduate student experience at many universities, including the University of Colorado Boulder. From our viewpoint as instructional designers, we wanted to know more about what large lectures are like for students today. We embarked on a project to explore student perceptions about large lecture courses and to better understand the various realities that students in these classes confront.

Institutional Context and Research Approach

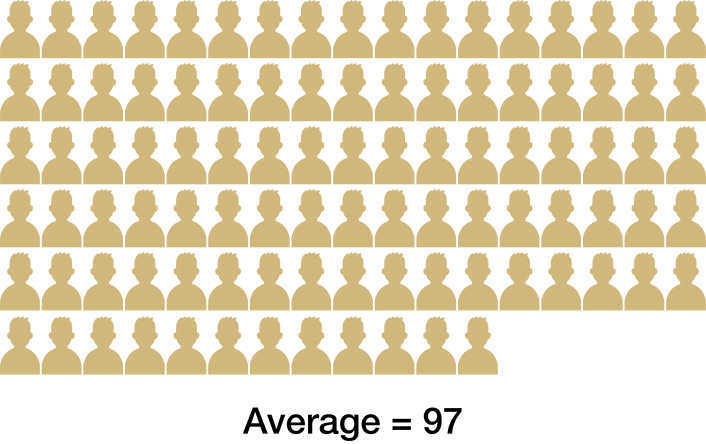

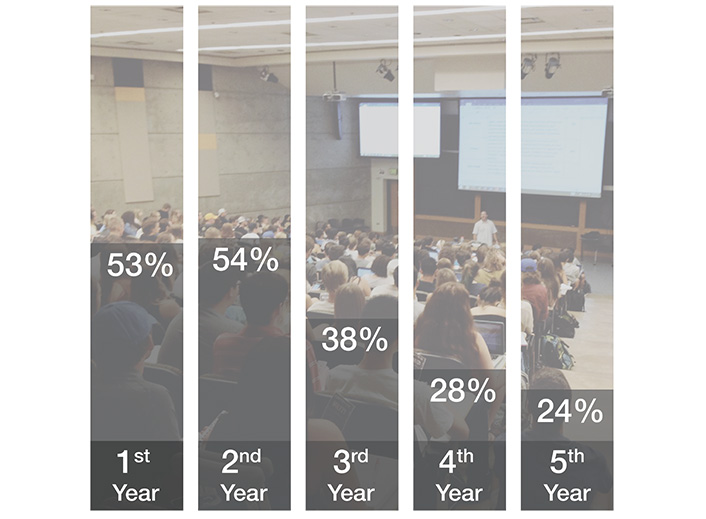

There is no standard for what constitutes a large lecture class; this project defined large lectures as those with 75 or more students enrolled. At CU Boulder, the average class size is 97 students and the median is 51 students. Large lecture courses constitute a sizable proportion of student course loads, particularly among first- and second-year students (see figures 1 and 2).

Our discovery work was guided by these questions:

- How are students currently being engaged? What methods work best for student engagement in large lecture classes?

- What strategies and resources can we provide to help students succeed in large lecture courses? What pedagogical recommendations can we provide for instructors of large lecture courses?

- What structural changes could the university consider to better support all types of learners?

We sought data about student attitudes and preferences regarding large lecture courses. To that end, we conducted the following activities between Fall 2016 and Spring 2018:

- Planned research methods and a timeline for semester-long discovery work.

- Conducted preliminary investigations into student experiences and perspectives on large lectures and used information collected to create a student survey that was distributed campus-wise in May 2017.

- Conducted observations of large lecture classes.

- Analyzed research results and developed data visualizations.

- Provided the Office of Information Technology (OIT) and the campus community with research results and recommendations for improving the large lecture student experience.

Campus-Wide Student Survey

The student survey consisted of 17 questions of varying formats. Among the topics covered, the survey asked students about the frequency and the sources of distractions in large lecture courses, as well as what helps keep them focused in those courses. We asked students what instructors could do to limit distractions and improve engagement, and we inquired about steps students have personally taken to improve their learning in large lectures.

This online campus-wide student survey was distributed via our internal campus newsletter and OIT's social media channels between May 3, 2017 and June 1, 2017. Eighty students completed the survey, with response counts varying by question. Although this response rate limits our ability to extrapolate the findings, the results are insightful for our campus community, help guide our future work, and warrant further exploration.

Findings

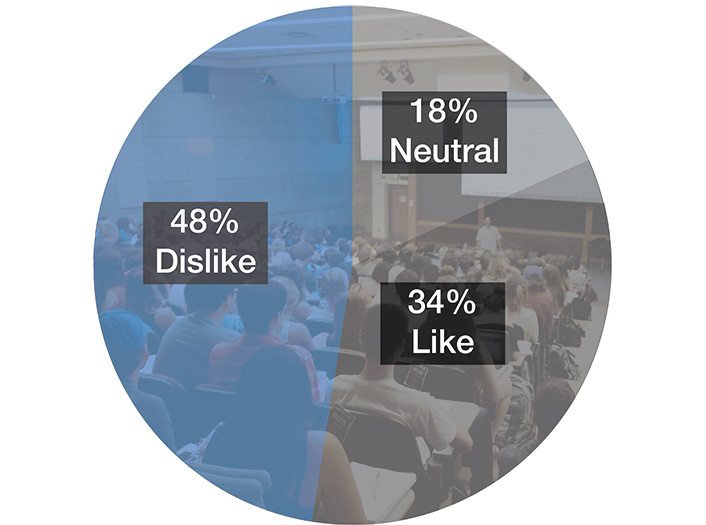

Throughout our discovery work, we found that students often hold a generally negative perception of the large lecture course format (see figure 3). This negative perception seems to be fueled by the challenges surrounding learning in large lecture courses. The most significant challenges for large lectures on campus relate to issues of distraction and engagement.

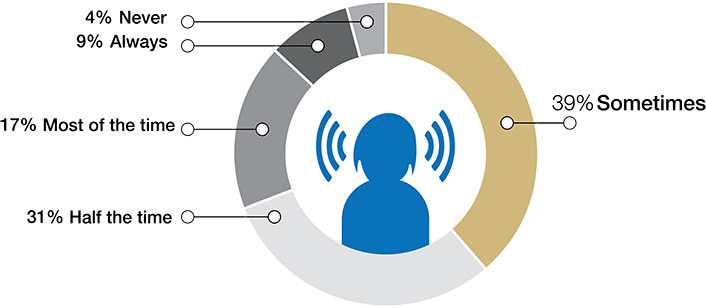

While we recognize that students are at least sometimes distracted during classes, a key takeaway from survey responses is that a combined 57% of students indicated that they are distracted half of the time or more in large lecture courses (see figure 4).

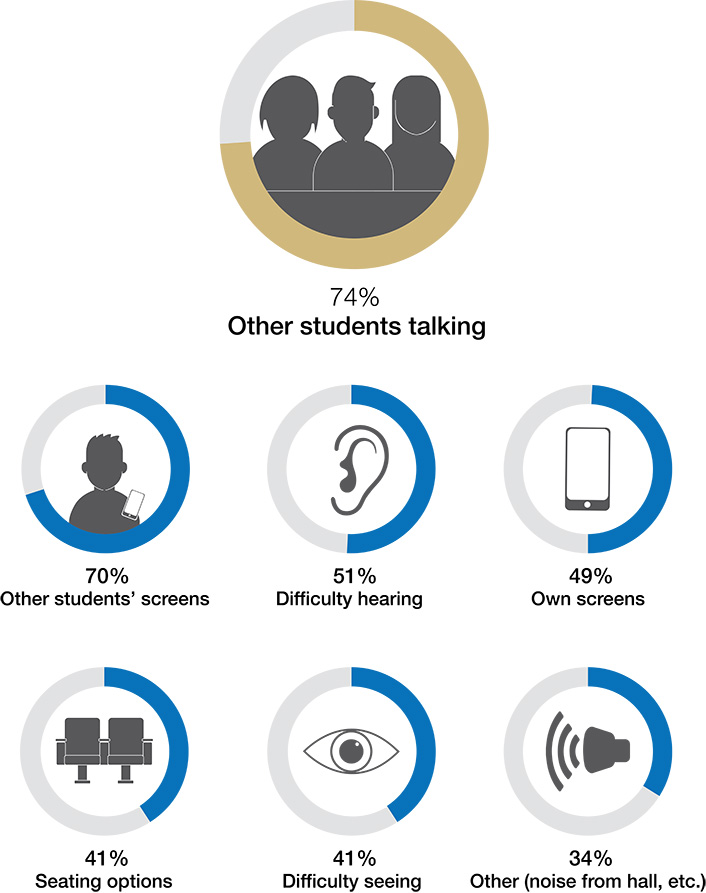

Student distraction is most often caused by factors that could be mitigated by direct, real-time intervention from instructors or teaching assistants. The top two causes of distraction stem from the behavior of other students in the classroom: 74% of students reported being distracted by other students talking, and 70% by other students' screens/devices (see figure 5). Other significant challenges include difficulty hearing the instructor (51%) and seeing lecture materials and presentations (41%). These causes of student distraction could in part be addressed by instructors' improved use of classroom technology, such as microphones and clearly visible presentation formats.

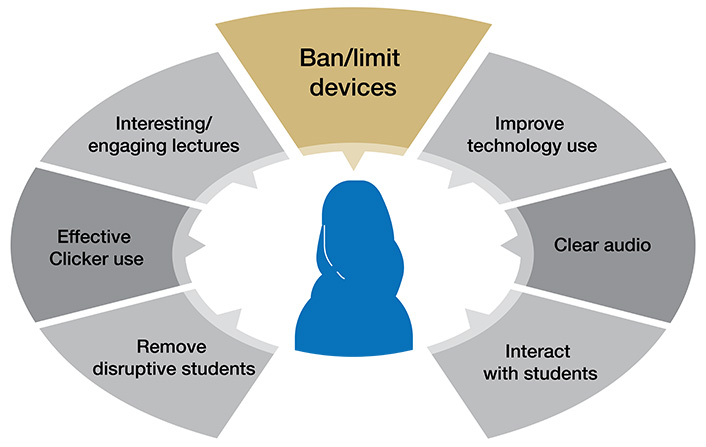

Student suggestions for mitigating distractions include instructors banning or limiting device use in the classroom (see figure 6). Although students suggested banning devices or limiting their use to specific zones in the classroom, they also recognize that device-related accommodations are necessary in some cases for students who have disabilities. Additional suggestions included fostering student engagement with the course material through interesting lectures or presentations.

The majority of respondents (93%) indicated that an "interesting instructor" improves their ability to stay focused in a large lecture course (see figure 7). Although this is a rather vague concept, this data point highlights the importance of intentionally designing engaging learning experiences and connecting with students. To improve engagement, students recommended more facilitated interaction with instructors, TAs, and peers through active learning activities in classes (group discussion or work, effective clicker use, facilitating study groups). The perceived lack of connection with instructors could be mitigated through instructors learning students' names, providing more opportunities for office hours (online, with TAs), and connecting lecture material to students' lives.

In addition to the suggestions above, the physical realities of large lecture classrooms merit further investigation. More than one-third of students (34%) indicated that they are distracted by background noises (such as noise from hallways), and 41% indicated that classroom seating options are not ideal for engaged learning. Tightly-spaced auditorium-style seating in lecture halls results in a number of seats going unused and, in some cases, students deciding to sit on the floor rather than squeeze past other students for a seat. These seating arrangements also put many students at a distance from the instructor, making it difficult to participate, see, and hear.

Outcomes and Next Steps

Although our research is limited by the number of responses and cannot fully address the challenges of today's large lecture courses, we found this discovery-focused approach to be a fruitful discussion starter with instructors and constituent groups. We shared the results with internal work groups and the campus community through various committee meetings and campus symposia. We created several resources that have been shared across campus:

- Infographic: The Student Experience in Large Lectures at CU Boulder

- Large Lecture Tips for Students

- Large Lecture Tips for Instructors

The data have allowed us to better communicate student preferences to instructors, and the results informed our final report. As a result of this research, AV equipment was updated in several of large lecture classrooms, and the data have also guided our work in designing large lecture courses and providing faculty with support and professional development. Recommendations included conducting similar discovery work at regular intervals and broadening the work to collect comparison data for smaller classes.

By sharing our process, we hope to provide one method for gaining insight into the foundations of institutional challenges for courses that are a significant part of most students' time in college.

Amanda Seal McAndrew is the Faculty Services Portfolio Manager for ASSETT (Arts and Sciences Support of Education Through Technology) on the Academic Technology Design Team in the University of Colorado Boulder's Office of Information Technology.

Tarah Dykeman is a UX Researcher on the Academic Technology Design Team in the University of Colorado Boulder's Office of Information Technology.

Courtney Fell is a Learning Experience Designer on the Academic Technology Design Team in the University of Colorado Boulder's Office of Information Technology.

Ben Nussbaum was formerly a Graphic Designer on the Academic Technology Design Team in the University of Colorado Boulder's Office of Information Technology.

© 2018 Amanda Seal McAndrew, Tarah Dykeman, Courtney Paige Fell, and Benjamin Nussbaum. The text and graphics of this work are licensed under a Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 International License.