The information security of institutions of higher education is literally a matter of national security. In a recent joint report, the Department of Homeland Security and the FBI identified U.S. educational institutions as one of the types of organizations that have historically been targeted by ongoing campaigns of "malicious cyber activity" such as spearphishing campaigns, "leading to the theft of information ... [and] attacks on critical infrastructure networks."

October is National Cyber Security Awareness Month, and EDUCAUSE is pleased to be able to contribute to this ongoing discussion. NCSAM focuses on a different cybersecurity issue each week. The focus for October 23–27 is "the shortage of cybersecurity professionals" and "encourag[ing] students and professionals to explore cybersecurity as a viable and rewarding profession." In this brief post, we present some data from the recent EDUCAUSE Center for Analysis and Research (ECAR) report on chief information security officers about the background and career trajectories of CISOs and how those aspiring to be CISOs can prepare for the role.

The NCSAM website argues that "it is essential that we graduate students entering the workforce to fill the vast number of positions" in information security that will potentially go unfilled, even in the next five years. It is important to note, therefore, that CISOs are relatively young for IT leaders in higher ed. The youngest CISO to respond to the ECAR survey was 28, and the median age was 49. While 49 is hardly fresh out of school, the fact that CISOs are young by the standards of higher ed leadership speaks to this urgency to fill CISO positions, as there is simply less time to prepare CISOs than other higher ed C-suite positions.

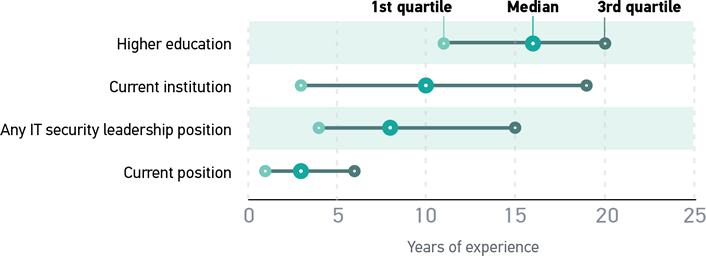

Moreover, preparing CISOs falls largely to the CISO's own institution. Many institutions like to "grow their own" leadership by grooming employees over their career at the institution to fill progressively higher positions, and this is especially true for CISOs. The ECAR study found that the previous position held by 52% of CISOs was at their current institution, and the position prior to that was at the same institution for 30%. CISOs have been at their current institutions for a median of 10 years; given that CISOs are among the youngest IT leaders, these individuals have been at their current institutions for a significant percentage of their working lives.

Many CISOs have come up through the ranks of information security positions at a single institution. It therefore clearly falls to institutions of higher ed to help prepare their own information security professionals to become CISOs. What can institutions do to help "grow their own" information security leadership?

Many CISOs have already earned one or more information security–related professional certifications — fully two-thirds of CISOs already have the Certified Information Systems Security Professional (CISSP) certification, for example. And a significant percentage of CISOs aspire to earn almost every certification that ECAR asked about on the survey: Certified Information Security Manager (CISM), Certified Ethical Hacker (CEH), Certified in Risk and Information Systems Control (CRISC), and several others. Indeed, 53% of CISOs said they intend to earn another certification within the next five years. It seems clear that information security professionals are well aware of both the salary benefit of certifications and the extent to which hiring committees look for certifications on applicants' resumes, and many individuals are actively seeking more of those credentials.

Credentials such as these provide training and experience with the technical side of information security work, which is of course critical for doing the job. Although technical expertise is necessary, it is not sufficient. Respondents to the CISO survey were asked for advice to give to aspiring information security leaders, and the most prominent theme that emerged was the need to develop "soft skills." One respondent wrote that soft skills "are what will help you to succeed," while another suggested that they are "far more valuable and durable than technical skills." Indeed, yet another recommended that one should learn soft skills first because "the hard skills are much easier to develop." Soft skills are of course important to any leadership position, but they are critical for information security leadership, which relies so heavily on buy-in by all campus stakeholders.

What institutions can do to help "grow their own" information security leadership, therefore, is to provide information security professionals with professional development opportunities, both to build technical expertise, and (arguably even more importantly) to build soft skills. The NCSAM website argues that "growing the next generation of a skilled cybersecurity workforce — as well as training those already in the workforce — is a starting point to building stronger defenses." In higher education, cybersecurity leadership begins at home.

Jeffrey Pomerantz is a senior research analyst for EDUCAUSE.

© 2017 Jeffrey Pomerantz. This EDUCAUSE Review blog is licensed under Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0.