Transforming Higher Ed

A blog about breakthrough tech-enabled innovations supporting student learning and college completion

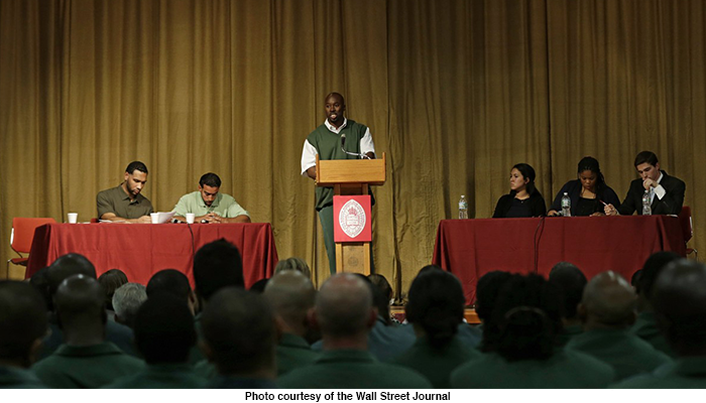

In early October in New York, three talented and motivated prison inmates from the Bard Prison Initiative inspired the nation by defeating Harvard University’s debate team on the topic of public education for undocumented students. The inmates’ success served as the perfect punctuation mark for the September 30th deadline for institutions to apply for Pell for Prisoners. This experimental sites project enables prison inmates to obtain federal Pell grants to finance their college education while behind bars.

For the adult prison population, the benefits of a college education, combined with supportive re-entry services, are undeniable. Postsecondary education, in particular, appears to have a more powerful effect in reducing recidivism compared to other levels of education. A 2013 RAND meta-analysis that synthesized the findings of 50 studies on recidivism revealed that a person receiving postsecondary education in prison would be about half as likely to recidivate as someone who does not receive postsecondary education in prison. The social benefits are just as clear: in terms of direct costs, for every dollar invested in a prison education program, the country would save $4 to $5 of taxpayers’ money in re-incarceration costs. Unfortunately, however, only about one-third of prisons offer any sort of postsecondary credential; most prisons, approximately 76 percent of systems, focus on secondary education and GED programs.

The opportunity to join the social and political reform movements to create pathways from corrections to college and beyond is undeniably attractive. Many online providers in particular might view Pell for Prisoners as a chance to educate this hugely underserved population especially when online technologies are becoming so sophisticated. The challenges, however, of working within the correctional system are vast and complex to say the least. Many processes and resources that a university may rely upon to deliver online education or online competency-based education at scale can easily fall apart when it comes to implementation in this particular context.

Major Challenges

-

Technology: Internet technologies have already been incorporated into many areas of correctional facility life, but they are less prevalent in correctional education programs. Students have limited access to computers and tablets, and only 14 percent of prisons allow restricted direct Internet access for their students. Very few use interactive or two-way Internet-based or video instruction. The primary reason why most corrections facilities have not provided their students with greater access to advanced technologies is security breaches. Corrections administrators are also concerned about costs for equipment, software, licensing and subscription fees, as well as costs associated with networking or communications.

Not only do inmates have relatively limited access to technology and communications, but they also may have lower than average familiarity with technology: 41.2 percent of the US adult prison population is over the age of 40; they may not be “digital natives” and may struggle with learning new technologies. Therefore, some form of basic IT skills training may be necessary before the students can participate in online learning, in addition to all of extra remediation or developmental education, soft skills and social skills development possibly needed for a positive and successful learning experience.

- Funding: Certain states do provide some postsecondary correctional education funding, but most have experienced budget cuts since the last recession. While approximately 32 states in the country offer some form of college or postsecondary courses to incarcerated adults, the average state has cut postsecondary education funding by 23 percent. Interestingly, some of the states with the biggest decreases in education funding in recent years are also those with the nation’s highest incarceration rates. Nevertheless, it is the responsibility of the inmates and their families to pay for these programs, which explains why many of these programs are underutilized.

- Scale: When it comes to online education for the prison population, scale turns out to be the most eye-opening challenge. It turns out that the U.S. criminal justice system is highly decentralized. Priorities may differ from state to state, county to county, warden to warden, and each system has its own way of delegating decision-making responsibilities. Popular program offerings in one region may be practically or politically unpalatable in another. The additional requirements of compliance from state to state add a whole new layer of complexity. Ultimately, even if a pilot were to work in one prison, the decentralization of corrections facilities makes it inordinately difficult to replicate and scale that nationally across the prison population—not to mention, simply across a single state.

- Resources: Online education providers would likely need to recreate all digital resources for an offline environment. Such resources would need to be scoped out in advance and whitelisted as education-focused resources, direct downloads, or mirrored open educational resources (OERs like Khan Academy, Purdue OWL, Open Courseware, Federal Trade Commission resources and other repositories of learning resources). This would require establishing agreements to provide hard copies of online content as well as licensed reseller agreements with established educational publishers, vocational training service providers, and other companies and organizations offering targeted reentry resources. To be safe, institutions would simply need to expect that their courses or competencies would be accessed entirely offline.

Signs of Hope

A sea change is occurring in corrections. There is no doubt that infrastructure problems are improving, but early technology implementations are piecemeal and incomplete. Early implementers have experienced success in using online-based instructional tools and resources to provide education and skills training to incarcerated students. Using a restricted Internet connection (RIC), the city of Philadelphia partnered with Jail Education Solutions (JES) to undertake a pilot program providing tablets to incarcerated individuals in select secure facilities. The city now uses JES to provide postsecondary education, vocational programing, cognitive therapy, literacy, and financial literacy. In Oregon, the Oregon Youth Authority (OYA) and its partners are introducing online open educational resources and college courses in the state’s juvenile facilities. OYA’s initiative focuses on self-paced learning via computer-assisted instruction that can be supervised by a person other than a licensed classroom teacher. A growing number of mobile device vendors have adopted the correctional education market as their niche. These vendors equip corrections facilities with tablets or other devices for use in and out of the classroom and typically provide educational content on their devices.

It will be fascinating to see how Pell for Prisoners unfolds. There are incredible programs like the Prisoner Reentry Institute (PRI) at the City University of New York (CUNY), the Prison University Project (PUP) at the Saint Quentin State Prison in California, and Bard Prison Initiative that already bring postsecondary education into prisons. It is also understandable why these organizations work with smaller numbers of inmates through a face-to-face format. For online learning providers, the way ahead may be less clear. Hopefully in the near future, we’ll see new and more developments in technology that may help solve some of the technical barriers of delivering and scaling an online education in America’s prison systems.

Dr. Michelle R. Weise is the Executive Director of Sandbox Collaborative, the R&D arm of strategy and innovation at Southern New Hampshire University. Check out her earlier NGLC guest posts "Welcome to the Sandbox" and "Hey, Princeton: Consider Competencies". Follow her on Twitter @rwmichelle.