An intentional approach to course design can overcome the isolation that many feel in online courses.

Online asynchronous courses have become a common part of the college experience for many students in the United States. As of fall 2022, about 54% of all postsecondary students were enrolled in at least one online course.Footnote1 Students choose online courses for the scheduling flexibility and greater accommodation options they provide for students with disabilities.Footnote2 Despite these benefits, online students often feel isolated and disconnected from their classmates and the instructors.Footnote3

Isolation and difficulty engaging with other students and instructors are not, however, immutable characteristics of online courses. We witnessed first-hand a successful model of student engagement in an online course (EPSY 5261, an introductory statistics course for graduate students at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities) that used a cooperative learning approach to create engaging, promotive interactions between students and instructors. This structure can be implemented in other online settings.

What Is Cooperative Learning?

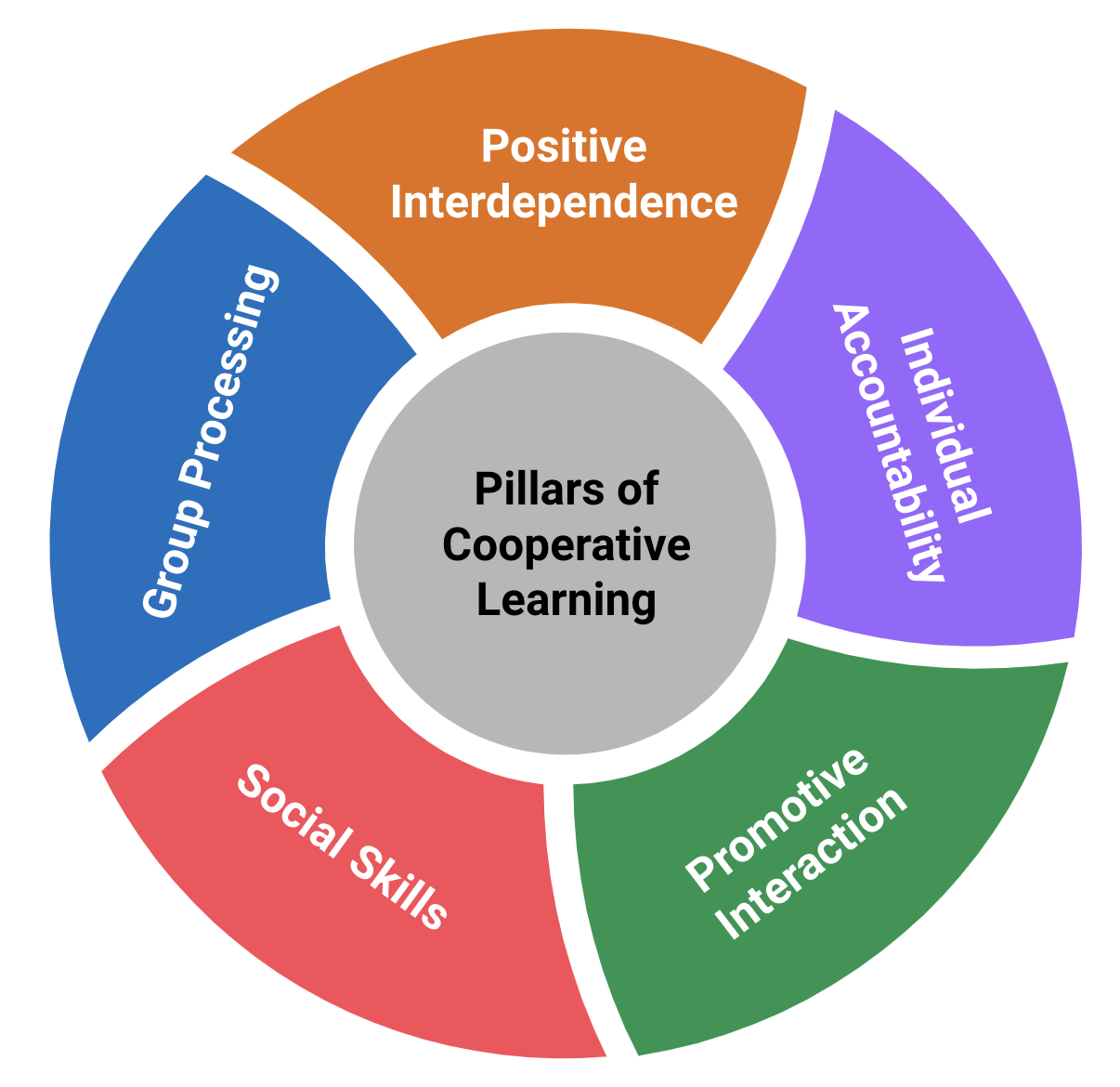

Cooperative learning is an evidence-based instructional practice that emphasizes active student participation and engagement.Footnote4 Cooperative learning posits that structuring the learning environment to optimize peer interactions will lead to better student learning outcomes than other instructional practices, a finding well supported by empirical evidence.Footnote5 Establishing a cooperative learning environment rests on five pillars: positive interdependence, individual accountability, promotive interaction, social skills, and group processing (see figure 1).

In cooperative learning environments, students are first placed into "base groups" of approximately three to four students. Each student must be taught to believe that working together will maximize each student's own learning, that every group member's contribution is essential, and that no individual can succeed unless all members of the group succeed. This is positive interdependence. Additionally, each student must be held responsible for their contributions to the group to ensure individual accountability for learning.

Given these dispositions, students must then promote everyone's success by helping and encouraging each other in their learning. A key factor in achieving these promotive interactions is fostering social skills so that students are able to communicate effectively with one another, manage conflicts and disagreements appropriately, and make decisions as a team. As with any process, these practices are rarely implemented perfectly at the onset of learning. Group processing activities allow students to reflect on their interactions with an eye toward continuous improvement.

Barriers to Online Interactions

Although cooperative learning has been applied to a variety of classrooms across educational levels, domains, and settings, its use in online asynchronous learning environments conflicts with one of the model's pillars—in the original cooperative learning framework, promotive interactions are specifically described in terms of face-to-face interactions.Footnote6 In-person interactions are fundamentally different from online interactions.Footnote7 Online interactions lack nonverbal cues, and the absence of such cues can interfere with effective communication. "Reading" a classmate's opinions without body language and other signals can affect the way students perceive each other. Additionally, online interactions provide potentially deleterious opportunities for anonymity that in-person interactions generally do not.

Together, these differences are potential barriers to establishing promotive interactions in online asynchronous courses. Evidence suggests that students in online discussions typically focus on individual perspectives and generally do not support each other's learning.Footnote8 This lack of promotive interactions may partially explain why many students feel isolated in online courses.

An Online Cooperative Learning Workflow

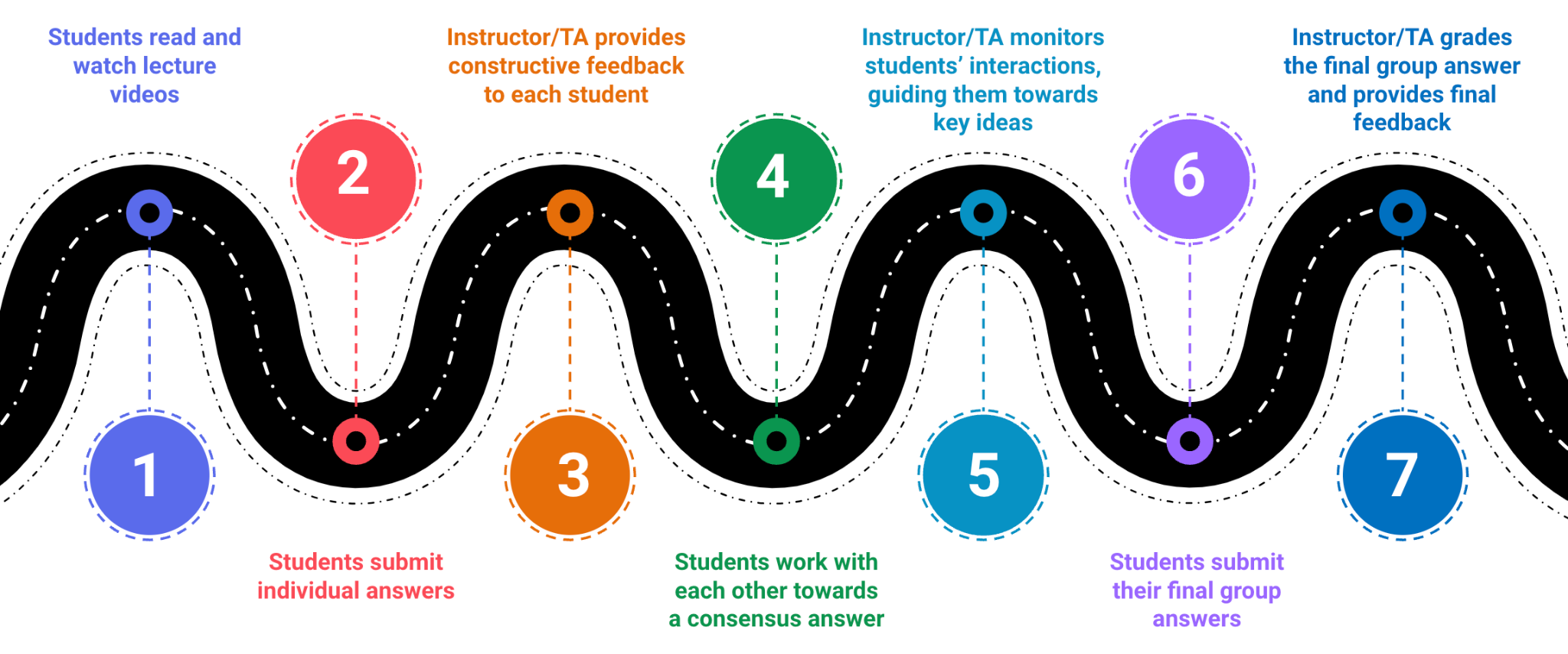

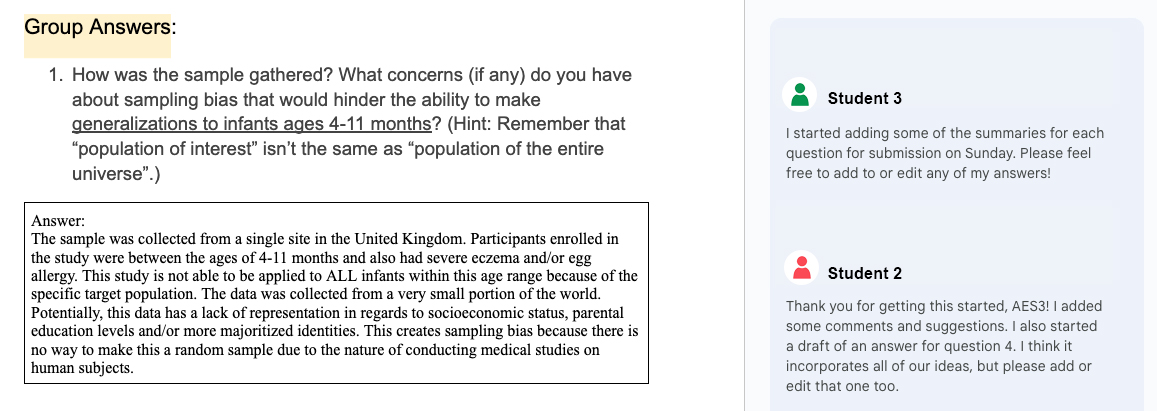

A course design based on cooperative learning principles is one way to address the lack of promotive interactions in an online course. The online cooperative learning course design is based on a seven-part workflow (see figure 2). For each unit or section of course content, students move through the same seven steps to deepen their understanding of the material and work with their peers to reach consensus. The interactions are paced using multiple due dates within each week so that students move through the material together. Throughout the workflow, the instructor and teaching assistants provide feedback and guidance, gradually stepping back as students develop greater competence, social skills, and group problem-solving processes over the duration of the term.

Step 1: Lesson Content

Students engage with course materials such as lecture videos, readings, and tutorials to gain a foundational understanding of the current topic.

Step 2: Individual Student Answers

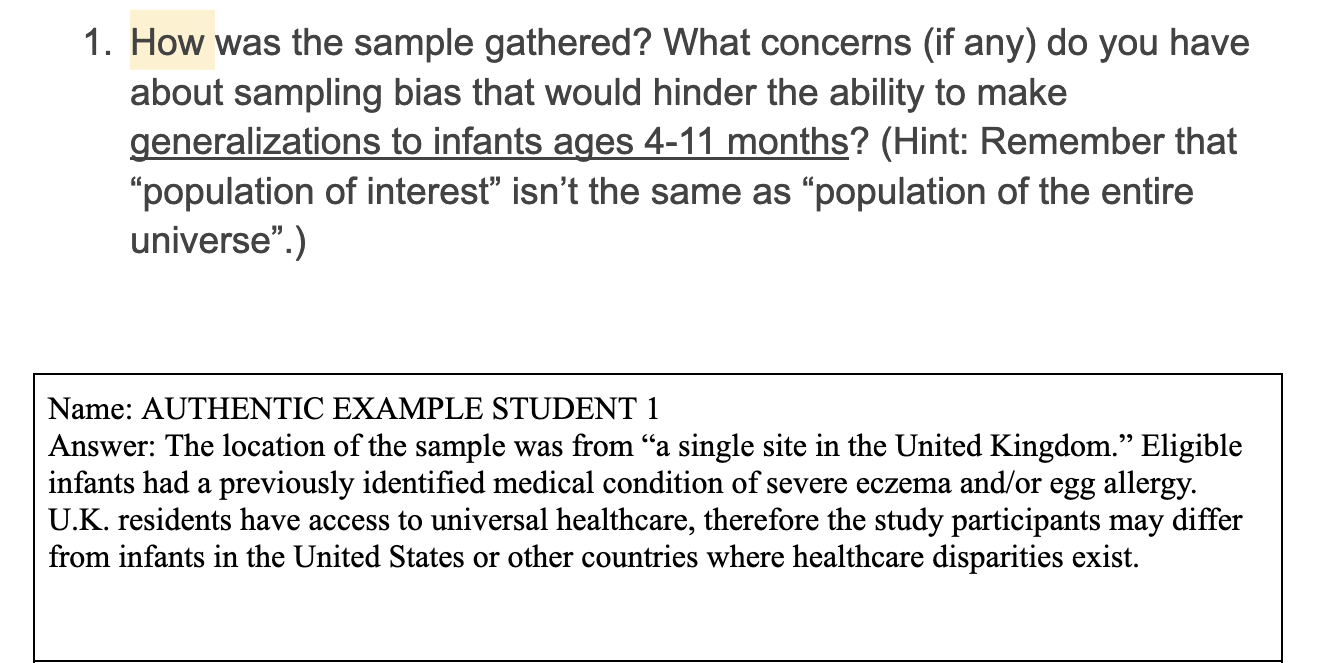

Students complete a set of homework problems on their own, posting their initial responses in an online document that is shared with their base group (see figure 3). The problems in EPSY 5261 include basic comprehension questions, reading response, case studies, and skills practice using statistical software such as R or StatCrunch.

Step 3: Instructor Constructive Feedback

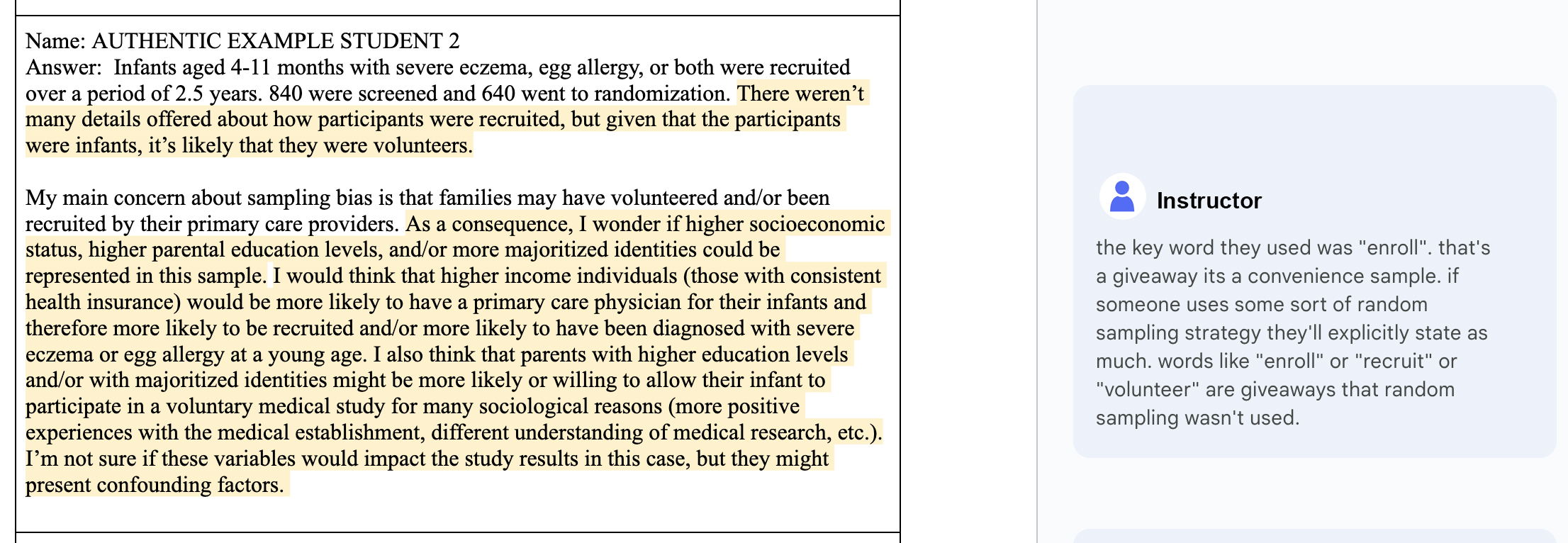

The instructor or teaching assistant reviews the individual student responses to the homework set, entering comments into the document to clarify concepts or point to course materials that the students should review to correct or refine their responses (see figure 4).

Step 4: Promotive Interactions

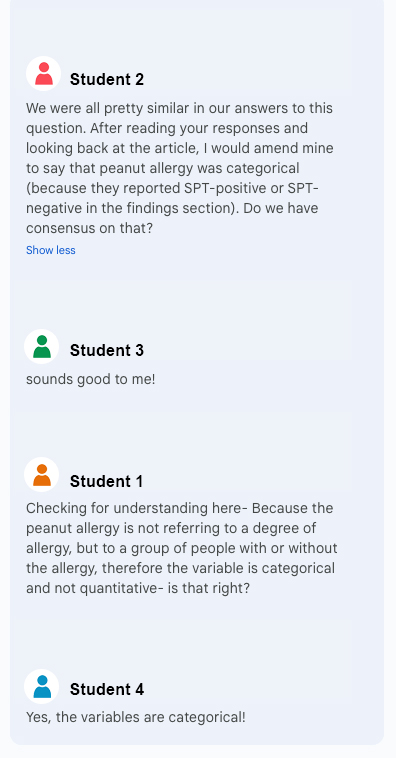

Students review each other's responses and the instructor's feedback (see figure 5). Using the comment feature in the shared document to discuss each question, students work together to arrive at a group consensus response.

Step 5: Continuous Monitoring

The instructor or teaching assistant continues to monitor students' interactions, asking questions to engage them in critically thinking about the key ideas in each unit, acknowledging and championing each individual member of the group and supporting the group's promotive interactions.

Step 6: Final Answers

Each base group submits one homework set for credit that reflects the group's consensus responses (see figure 6).

Step 7: Final Feedback

The instructor provides final feedback to each group as necessary based on the accuracy and completeness of their final responses.

In addition to this workflow, EPSY 5261 included two summative assessments that students completed individually. Because the content and format of the summative assessments reflected the collaborative assignments, students had received instructor and peer feedback on the central course concepts and skills before being asked to demonstrate their learning on the midterm and final exams.

To see a complete, anonymized example of a cooperative learning assignment, visit https://tinyurl.com/Example5261Activity.

Our Experiences in EPSY 5261

In this online course, we personally experienced the benefits of its cooperative learning model, benefits particular to our roles as student (May) and instructor (Rao).

May's Perspective

I am an instructional designer, a graduate student, and a parent. I registered for the online asynchronous section of the statistics class primarily for flexibility. I was moderately confident in my math skills, but I wasn't sure what to expect in a fully online class. Dr. Rao began the semester with written information and a video explaining the structure of the course and his approach to the statistics content. This immediately set a tone of openness and clarified the role of students in the course. As we moved into our base groups and began our cooperative assignments, there was some awkwardness at first as we sorted out who would start conversations and how we would decide when a question response was finalized, but once we worked out those dynamics, I found that my group was able to have productive and detailed discussions about the statistics concepts through the document comments feature as we refined and worked toward our collaborative responses. We clarified concepts together, and when we got stuck or took a wrong turn, Dr. Rao or the TA would jump in to get us back on track. In contrast to other asynchronous courses I've experienced, which were primarily based on discussion boards, these course activities felt purposeful and my interactions with peers felt genuine because we were working toward a common goal. I felt more confident going into each of the summative assessments knowing that I had thoroughly processed the concepts and practiced the skills. And I was surprised by the accountability I felt toward the three other people in my group whom I had never met in person or even on a video call. It really felt like peer learning.

Rao's Perspective

I am an educational psychologist and statistician. At the time that I taught EPSY 5261, I was a fourth-year graduate student studying statistics education. My TA was a first-year graduate student in the same program. My TA and I prioritized having deep and meaningful interactions with the students—the overwhelming majority of our instructional time was spent in asynchronous interaction with students through the document comments feature. Because the course was asynchronous, I gave no lectures. Additionally, all assessments aside from the cooperative learning assignments were auto-graded. More or less the only time I spent on the class was in the shared documents. I had 45 students in 10 groups. Reviewing the initial posts took approximately three to four hours for all students, and checking in on them twice more throughout the week took an additional one to two hours each time. I felt that teaching such a course was actually less work than teaching an in-person synchronous version of the course, while also allowing me to have deeper and more meaningful interactions with my students. By the end of the term, I felt like I had gotten to know many students despite never having met them in person. Today, I am in touch with more students from the online sections I taught than the students from the in-person sections I taught.

Adapting the Cooperative Learning Workflow

Using shared online documents is one way to achieve promotive interactions that help foster cooperative learning. The cooperative learning workflow can be adapted for any university-level course, whether at the undergraduate or graduate level. Faculty and staff implementing the workflow in other online settings can consider the following recommendations:

- Include open-ended tasks: Promotive interactions require a context to facilitate interactions. The most effective moments in our class were when there was confusion or disagreement among students in a base group. When ambiguity or debates arise, students have a genuine reason to interact with each other and explain their understanding of the course content. This also provides an opportunity for the instructors to highlight tensions and help the members of the group reframe their thinking.

- Champion every student: It is natural for some students to feel as if they are "carrying" the group. By championing every student through encouraging comments and specific guidance, an instructor can demonstrate the value that each student brings to the group. This fosters the more effective social skills required for promotive interactions and results in more evenly distributed participation.

- Reduce instructor workload elsewhere: Instructors should ensure they have time to provide deep and meaningful feedback to every group of students. This work may also be shared among teaching assistants or other instructors teaching the same course. To balance their time, instructors of EPSY 5261 do not record new lecture videos every term. Students may end up watching videos of other professors explaining the core course concepts; however, they have frequent interactions with the instructor of record in the shared document, ensuring that they do directly benefit from their instructor's expertise.

- Actively inculcate the social skills and practices necessary for promotive interactions: Students need to be taught how to interact with one another. Therefore, especially in the first few weeks of class, it is imperative that the instructors are highly active in each group's document, replying to each student but also encouraging student interaction. For example, an instructor can leave a comment on a student's answer to a question specifically referencing another student's response and asking both students to work together to arrive at a consensus answer. This is especially true for students unfamiliar with cooperative learning environments.

- Gather student feedback and be prepared to iterate: Include opportunities during and after the term for students to share their learning experiences in the course and provide feedback on what is working well and what could be improved. When implementing a new cooperative learning workflow, instructors will likely need to make adjustments to fine-tune the course to meet the needs of the specific content, students, and educational environment.

Conclusion

Students can feel isolated and disengaged in online settings. The promotive interactions and positive interdependence facilitated by cooperative learning activities offer opportunities for students to get to know each other and engage deeply with the course content. Promotive interactions may not occur spontaneously in online asynchronous courses, but thoughtful instructional design can overcome this barrier. By incorporating theories of cooperative learning into an online course, we have experienced first-hand that promotive interactions are possible in the asynchronous environment, helping students feel connected to each other as well as the instructors.

Notes

- U.S. Department of Education, "Table 311.15. Number and percentage of students enrolled in degree-granting postsecondary institutions, by distance education participation, location of student, level of enrollment, and control and level of institution: Fall 2021 and fall 2022," Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics, 2023. Jump back to footnote 1 in the text.

- Jenay Robert, "2022 Students and Technology Report: Rebalancing the Student Experience," Research report (Boulder, CO: EDUCAUSE, October 2022). Jump back to footnote 2 in the text.

- Marcia D. Dixson, "Creating Effective Student Engagement in Online Courses: What Do Students Find Engaging?" Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning 10, no. 2 (2010): 1–13. Jump back to footnote 3 in the text.

- David W. Johnson and Roger T. Johnson, "Using Technology to Revolutionize Cooperative Learning: An Opinion," Frontiers in Psychology 5 (October 12, 2014); and Robert E. Slavin, "Instruction Based on Cooperative Learning," in Handbook of Research on Learning and Instruction, eds. Richard E. Mayer and Patricia A. Alexander (New York: Routledge, 2011), 358–374. Jump back to footnote 4 in the text.

- Heisawn Jeong, Cindy E. Hmelo‐Silver, and Kihyun Jo, "Ten Years of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning: A Meta-Analysis of CSCL in STEM Education During 2005–2014," Educational Research Review 28 (November 2019); Eva Kyndt et al., "A Meta-Analysis of the Effects of Face-to-Face Cooperative Learning. Do Recent Studies Falsify or Verify Earlier Findings?" Educational Research Review 10 (December 2013): 133–149; and Chang Woo Nam and Ronald D. Zellner, "The Relative Effects of Positive Interdependence and Group Processing on Student Achievement and Attitude in Online Cooperative Learning," Computers & Education 56, no. 3 (April 2011): 680–688. Jump back to footnote 5 in the text.

- David W. Johnson and Roger T. Johnson, "Making Cooperative Learning Work," Theory Into Practice 38, no. 2 (1999): 67–73. Jump back to footnote 6 in the text.

- Alicea Lieberman and Juliana Schroeder, "Two Social Lives: How Differences Between Online and Offline Interaction Influence Social Outcomes," Current Opinion in Psychology 31 (February 2020): 16–21. Jump back to footnote 7 in the text.

- Elizabeth Murphy, "Recognising and Promoting Collaboration in an Online Asynchronous Discussion," British Journal of Educational Technology 35, no. 4, (July 2004): 421–431; and Amy T. Peterson, "Asynchrony and Promotive Interaction in Online Cooperative Learning," International Journal of Educational Research Open 5, no. 3 (December 2023). Jump back to footnote 8 in the text.

Nicole May is an Instructional Designer at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities.

V.N. Vimal Rao is a Teaching Assistant Professor at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

© 2025 Nicole May and V.N. Vimal Rao.