Change fatigue is causing higher education staff to disengage and is negatively impacting institutions. By understanding the issue and implementing effective solutions, college and university leaders can help their institutions continue to move forward.

Have big changes in your institution seemed extra challenging lately? Have staff seemed more stressed than usual? Are they disengaged? It is likely not your imagination. A growing body of research shows a significant increase in staff disengagement over the last several years, and the indicators suggest that this trend will continue.Footnote1

Rapid change has always been a challenge for higher education institutions. They often struggle to keep pace with competing strategic demands, budgetary challenges, complex bureaucratic structures, and important compliance and privacy constraints. In recent years, however, the situation for faculty and staff in many institutions has gone from strain to distress. This shift seems to have been triggered by the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic. As multiple change demands have layered on one another—both inside and outside institutions—employees have become overwhelmed, causing a reduction in performance and engagement and leading to a phenomenon called change fatigue.Footnote2 Change fatigue underpins many of the challenges that higher education leaders—especially CIOs—are encountering, sometimes without realizing it.

The PESTEL framework can be used to illustrate the changes impacting higher education and the magnitude of these changes. This framework considers the political, economic, social, technological, environmental, and legal factors driving changes (see table 1).Footnote3

| P Political |

E Economic |

S Social |

T Technological |

E Environmental |

L Legal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Higher education leaders must find new strategies to identify when staff and organizations are in a state of fatigue and develop tools and methods to lead change initiatives—especially technology ones—under such conditions. Change fatigue has been increasing steadily since the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic and shows no signs of waning. Leaders do not have the luxury of waiting for change fatigue to subside, as the forces driving change remain in play. Instead, leaders need to develop new approaches to change management that take into account the environment that emerged during the initial phase of the pandemic.Footnote4

Defining Change Fatigue

Change fatigue is a debilitative state that parallels physical fatigue. It is a state of emotional and physical exhaustion brought on by frequent and intense changes, resulting in an individual's inability to adapt to and engage with new changes.Footnote5 All people have a set of psychological adaptive systems that allow them to adjust to new environments and processes, and each change a person experiences draws on those systems. When changes become too frequent or intense, those systems become overwhelmed. Before the pandemic, change fatigue was more often observed on an individual basis and could typically be attributed to personal circumstances. In the current environment, however, large swaths of entire organizations are impacted by fatigue.Footnote6 The workforce remains exhausted and has yet to recover from the collective stress of the pandemic, a situation made worse by ongoing societal, economic, political, and technological changes.Footnote7

Following are signs that someone may be experiencing change fatigue:

- Combativeness: A confrontational attitude toward new initiatives.

- Agitation: Reacting defensively or confrontationally, even to minor issues.

- Incivility: Increased rudeness or dismissiveness, or a lack of empathy toward others.

- Cynicism: A rising sense of skepticism about new initiatives.

- Absenteeism: An increase in the number of days an employee takes off.

- Declining performance: A noticeable drop in productivity or quality of work.

- Visible signs of exhaustion: Physical signs of fatigue, such as a slumped posture, frequent yawning, or dark circles under the eyes.

- Apathy: A lack of interest in work activities or a decline in engagement.

Understanding What Change Fatigue Means for Change Management

The Energy Commitment Model

Traditional change management focuses primarily on creating a desire for the specifics of change, operating on the belief that "resistance" can largely be overcome through a mix of awareness-building, knowledge-sharing, and other logical and analytical interventions. Once an employee reaches a sufficient level of desire, the individual will engage more fully with the change. In a non-fatigued environment, this argument is reasonable but incomplete. In today's dynamic and often overwhelming work environment, change fatigue presents a significant challenge that traditional models do not fully address. To better understand and manage this phenomenon, we developed the Energy-Commitment Model (ECM), which integrates insights from two theories: the workplace commitment model and the conservation of resources.[8] The ECM aims to clarify the relationship between employees' commitment to organizational change and their practical ability to act on that intention, particularly when change fatigue is prevalent.

The ECM is built around three main components: energy, commitment, and engagement threshold.

Energy (Resource Availability)

In the ECM, energy symbolizes the range of tangible and intangible assets an individual can mobilize to respond to change.

- Cognitive bandwidth: The mental capacity to understand, assimilate, and implement the desired change.

- Time: The temporal resources an individual can dedicate to learning new processes, systems, or behaviors.

- Emotional reserves: The psychological endurance required to navigate change, especially when facing resistance or inertia.

- Support network: The external support structures—both organizational and interpersonal—that an individual can draw upon during change.

This reservoir of energy can be channeled into actions, processes, and learning that supports organizational change.

Commitment (Energy Direction)

Commitment represents an employee's internal drive or inclination toward change and consists of the following three dimensions:

- Affective commitment: An employee's emotional alignment with the change, stemming from a personal identification with the transformation.

- Continuance commitment: An employee's pragmatic engagement with the change, arising from anticipated constraints or lack of alternatives.

- Normative commitment: An employee's sense of obligation, often influenced by organizational ethos or societal expectations.

The type of commitment an employee has toward change shapes how they direct their energy. For example, an employee with a strong affective commitment will passionately channel their energy, while someone driven by normative commitment might prioritize obligations.

Engagement Threshold

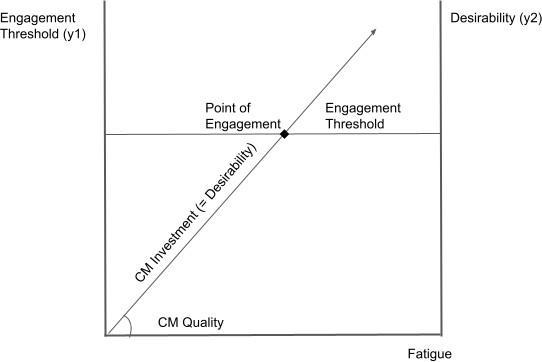

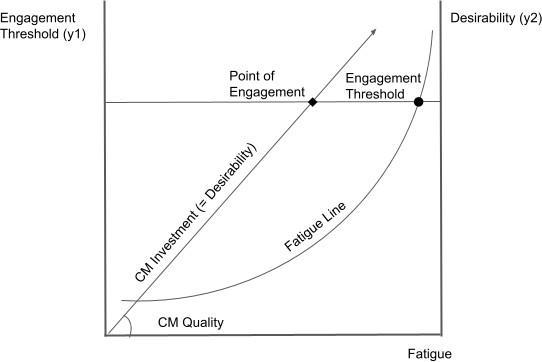

The engagement threshold is the tipping point at which an employee has sufficient energy and commitment to engage productively in the change. The ECM posits a direct correlation between escalating fatigue and a rising engagement threshold, underscoring the need for organizational interventions. In non-fatigued environments, the engagement threshold remains static (see figure 1).

However, in a fatigued environment, the engagement threshold is always changing. The level of interest (desire) needed for successful change management shifts based on how fatigued people feel. Historically, in non-fatigued environments, the difference between desire and fatigue levels has been small (see figure 2).

The ECM introduces a transformative perspective on change management, recognizing the critical interplay between energy and desire in individuals' readiness for change. Unlike traditional approaches that focus solely on increasing desirability, the ECM views energy and commitment as two essential levers that combine to reach the thresholds necessary to support change. In fatigued environments, individuals may require interventions to bolster both their energy levels and their desire for change before they can commit to and act upon proposed initiatives.

Moreover, the ECM emphasizes the crucial role managers play in navigating these complexities. Rather than solely aiming to maximize desirability or relying on past strategies, managers help guide efforts to identify optimal points of change adoption. This proactive approach ensures a more nuanced understanding of change dynamics and fosters the development of effective strategies for achieving sustainable change outcomes within organizations. By acknowledging the limitations of traditional approaches and actively addressing the energy-commitment equilibrium, managers can lead their teams toward successful change implementation, even in challenging and fatigued environments.

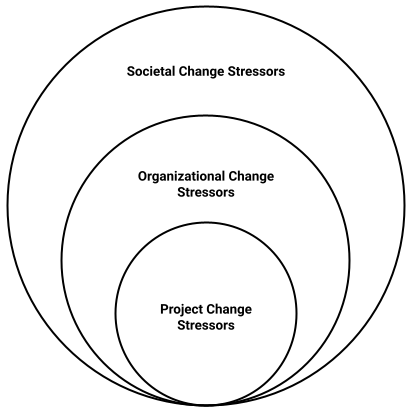

This new perspective alters the role of change management significantly. The need to conduct readiness assessments is more important than ever. These assessments should account for the number of other changes happening inside the organization and outside the organization broadly. Fatigue can be driven by changes happening in the micro (project/change initiative), meso (organizational), and macro (outside/societal) environments (see figure 3). For instance, social, political, and economic shifts should all be viewed as potential changes that employees are managing, as they can all contribute to fatigue. In addition, several new markers (such as the signs of fatigue listed above) should be evaluated as part of a change readiness assessment.

Rethinking Change Leadership

The prevalence of change fatigue does not mean that leaders should shy away from necessary organizational changes. As previously noted, the prevalence of fatigue does not eliminate the fact that change is needed for institutions to continue serving their communities effectively and to support teaching, research, and service. However, leaders need to be more aware of and transparent about the impacts of change on their organizations and more purposeful about the changes they pursue.

Change Fatigue Best Practices

During the planning stage for new initiatives, leaders can utilize the ECM to do the following things:

- Assess the general energy and commitment levels of their workforce.

- Anticipate potential areas of fatigue.

- Acknowledge fatigue in the organization.

- Strategize communication, training, and other change management activities and align them with identified needs.

During the execution phase, leaders can use the ECM as a monitoring and adjustment tool.

- Continuously monitor employee energy and commitment metrics.

- Monitor the markers of fatigue, such as turnover, engagement, and sick leave.

- Rapidly introduce interventions addressing emerging challenges or burgeoning fatigue.

- Periodically evaluate and refine the change management strategies based on feedback loops and observed outcomes.

Drawing on our thematic analysis, we have the following recommendations for leaders:

- Continuously monitor employee energy reservoirs. Establish a system for regular check-ins or feedback to gauge employees' current energy levels. Recognize and address signs of fatigue.

- Prioritize the quality of change management initiatives. This includes clear communication, relevant and well-designed training, and transparent feedback mechanisms to reduce misalignment or confusion that could intensify change fatigue.

- Differentiate change management investments based on departmental or individual needs. Not every change strategy will be universally effective, and the level of change management investment will vary among individuals. Therefore, personalized approaches—such as allocating additional resources to high-stress departments or offering specialized training for less experienced employees—can optimize engagement.

- Foster multifaceted commitment. Cultivate a culture that encourages diverse forms of commitment—affective (emotional), continuance (practical), and normative (obligation-based). Affective and normative commitment should be favored where possible. Use personalized communication and incentive strategies that appeal to the different commitment dimensions to ensure that enough energy is directed toward reaching the engagement threshold for the change.

- Proactively seek to increase the perceived desirability of the change for change-fatigued employees. This could involve spotlighting success stories from early adopters, incentivizing participation through rewards or recognition, or ensuring that employees value the long-term benefits of the proposed change or the costs of not changing.

- Provide tailored support for change-fatigued employees. Develop support strategies that respond directly to the needs of change-fatigued employees. Employee assistance programs or stress management workshops can offer resources to employees to help them restore their energy and better handle the demands of change.

Example: Implementing a New Learning Management System

Traditional Change Management Approach

In a traditional change management approach, the focus is primarily on communicating the specifics and the rationale for the change and pairing those with logistical aspects such as training sessions and technical support. Communication emphasizes the features and benefits of the new learning management system (LMS), and less attention is paid to addressing the emotional or motivational aspects of the transition specific to the unique project and context. Feedback mechanisms may exist for technical issues, but fatigue and varying levels of commitment among faculty and staff are not systematically monitored or addressed.

ECM-Informed Change Management Approach

In contrast, an ECM-informed approach recognizes the interconnectedness of energy and commitment in shaping individuals' readiness for change within the higher education context. Faculty and staff energy levels and commitment orientations toward the new LMS are regularly assessed. Assessments can be formal, or they can be informal, such as during already occurring conversations. The ECM-informed approach recognizes that negative responses, such as cynicism or combativeness, may be driven by factors outside the project and may be signs of fatigue. Tailored communication strategies and incentives are developed to appeal to diverse forms of commitment, including emotional attachment and practical necessity. Proactive efforts are made to increase the perceived desirability of the change, such as spotlighting success stories from early adopters and offering incentives for participation. Additionally, personalized support strategies are crafted to address the specific needs of change-fatigued individuals. For example, a director, chair, or coordinator could assess the workload of faculty and staff members who are particularly stressed and identify tasks that could be temporarily redistributed to other colleagues or support staff. This could involve reassigning nonessential duties or adjusting deadlines to provide temporary relief for faculty members experiencing high stress levels.

Also, leaders should facilitate open and transparent communication with faculty and staff members about the importance of self-care and workload management during times of change. Encouraging employees to prioritize their well-being and offering flexible deadlines or expectations can help reduce feelings of overwhelm and burnout so that faculty and staff can better cope with the demands of the new system. In addition, events in the meso or macro environments may demand that a project be delayed.

Conclusion

Change fatigue has always been around, but over the last several years, it has moved from a secondary issue to a primary concern that is significantly impacting project viability in many colleges and universities. Higher education technology leaders are challenged with meeting the urgent need for rapid technical change and an environment already fatigued by excessive change inside and outside the organization. While classic change management still has a significant role to play, the additional focus on open and transparent communication regarding self-care and workload management is critical. Acknowledging the state of the environment is critical as leaders work to further their understanding of the causes and implications of change fatigue. Understanding the causes and implications and identifying potential solutions are critical to moving our institutions forward.

Notes

- Jim Harter, "U.S. Employee Engagement Needs a Rebound in 2023," Gallup (website), January 25, 2023. Jump back to footnote 1 in the text.

- Heather Ead, "Change Fatigue in Health Care Professionals—An Issue of Workload or Human Factors Engineering?" Journal of Perianesthesia Nursing 30, no. 6 (2015): 504–515. Jump back to footnote 2 in the text.

- Chris Jeffs, Strategic Management (SAGE Publications, 2008), 29. Jump back to footnote 3 in the text.

- Vanessa Ratten, "The Post COVID-19 Pandemic Era: Changes in Teaching and Learning Methods for Management Educators," The International Journal of Management Education 21, no. 2 (July 2023): 100777. Jump back to footnote 4 in the text.

- Jeremy B. Bernerth, H. Jack Walker, and Stanley G. Harris, "Change Fatigue: Development and Initial Validation of a New Measure," Work & Stress: An International Journal of Word, Health & Organisations 25, no. 4 (December 2011): 321–337. Jump back to footnote 5 in the text.

- Khai Wah Khaw et al., "Reactions Towards Organizational Change: A Systematic Literature Review," Current Psychology 42, no. 22 (2023): 19137–19160. Jump back to footnote 6 in the text.

- Emily Rose McRae and Peter Aykens, "9 Future of Work Trends for 2023," Gartner (website), December 22, 2022. Jump back to footnote 7 in the text.

- John, P. Meyer and Lynne Herscovitch, "Commitment in the Workplace: Toward a General Model," Human Resource Management Review 11, no. 3 (Autumn 2001): 299–326; Stevan E. Hobfoll, "Conservation of Resources: A New Attempt at Conceptualizing Stress," American Psychologist 44, no. 3 (March 1989): 513–524. Jump back to footnote 8 in the text.

Joseph Drasin is Assistant Vice President for Enterprise Service Strategy and a Faculty Fellow in the Honors College at the University of Maryland College Park.

Tacy L. Holliday is an Adjunct Professor in the Doctor of Business Administration Program at University of Maryland Global Campus.

© 2024 Joseph Drasin and Tacy L. Holliday. The content of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 International License.