Six strategies can help develop intentional, effective structures to improve students’ digital experiences.

Most of us working in higher education these days understand that many incoming students have never known a world without technology that is centered around them as individuals. They are accustomed to using technology in all aspects of their lives and expect an intuitive, easy, and efficient consumer-grade experience. For some institutions, including the University of Arizona, the student digital experience leaves something to be desired—or at least it did five years ago. In 2018, after being at the university for just six months, I was asked to participate in the University of Arizona's strategic planning process and partnered with leaders in Academic and Student Affairs to craft a proposal I called Personal, Digital U. This proposal included the collective ideas of these leaders (with their permission) and expanded on those ideas to envision a holistic, unified digital experience that would make it easier for students to navigate a large, complex, highly decentralized R1 university. The proposal grew into a larger enterprise constituent relationship management (CRM) initiative, focused on the student experience, that received buy-in from university leaders and kicked-off in January 2019. In the four and a half years since, the university has transformed and unified the student digital experience. Six key strategies supported this work, and our teams learned many lessons along the way.

Strategy #1: Establish visible leadership to enable technology for the academic mission.

The role that I was hired for in November 2017, Executive Director of Student & Academic Technologies, was created to enable this strategy. Prior to my arrival, University Information Technology Services (UITS) leadership reorganized the IT organization to create executive-level positions that were clearly aligned to the organizational structures of our functional business partners. The goal was to make it easy for executive leaders outside IT to know whom to partner with to advance strategic initiatives and make IT easy to navigate. Prior to this restructuring, UITS was organized around technologies, not business outcomes. Our registrar, bursar, and others knew whom to work with for operational efforts, but it was challenging for anyone to understand how to move large, transformative efforts forward. Complex technology initiatives need a leader to facilitate decision-making and build a unified vision that the institutional community of contributors can collectively drive toward. That leader need not be in IT but must understand technology and be able to activate the necessary IT talent to deliver on that vision—and delivering on that vision needs to be that leader's number one job, not something that is done on the margin.

Strategy #2: Find the gaps by bringing the student voice to the center.

In the summer of 2018, my teams and I began facilitating collaborative discovery efforts centered around understanding the university experience through the lens of the students. Over the course of the next few years, we conducted first-year student experience journey-mapping sessions, empathy mapping, surveys, short campus intercept polling, and design studios (table 1 provides descriptions of these methods). All of this work was done in collaboration with partners in student services and academic units. Among our goals was to create shared awareness of how students experience the university and where they experience significant barriers.

| Method | Description |

|---|---|

| Journey Mapping |

Journey mapping visualizes the process someone goes through to accomplish a particular goal or achieve a particular outcome. Key moments of delight, frustration, and opportunity are highlighted through the process. At the University of Arizona, we developed a first-year student journey map to identify priorities for improving their digital experience. The journey map included key activities students work through in their academic, administrative, and student life. (See "Journey Mapping 101", by the Nielson Norman Group.) |

| Empathy Mapping |

Empathy mapping looks at individuals' attitudes and experiences as they relate to a specific experience, focusing on what the individual is saying, doing, thinking, and feeling. In parallel to the first-year journey mapping, the University of Arizona developed an empathy map for how students experience being new to the university. (See "Empathy Mapping: The First Step in Design Thinking," by the Nielson Norman Group.) |

| Survey |

The University of Arizona used broad-scale surveys of students to understand their perception of the communications they receive from the institution. The team noted bias in the data in terms of the demographics of students who responded; however, the data were foundational in formulating additional inquiry that was conducted through intercepts, defined below. |

| Intercept |

To combat the bias noted in the broad-scale survey we conducted about institutional communications, we developed a method of inquiry with students that we called Intercepts. To conduct the intercepts, the team developed very short (five-question) surveys and then walked campus with tablets to talk with students and ask them to complete the survey in real time. Candy was used as an incentive, and, where possible, student employees administered the intercepts to help students feel comfortable discussing their experiences. The method proved very successful in gathering input from a diverse audience. |

| Design Studio |

Design studios are small-group exercises that combine ideation, design (low-fi) prototyping, and critique to distill the collective best ideas that emerge during the session. Doing design studios with students was instrumental in understanding how they see a particular opportunity or challenge and how they might go about pursuing a solution (their mental model). Design studio is a common technique in user research. (See "Facilitating an Effective Design Studio Workshop," by the Nielson Norman Group.) |

The learnings from our student discovery efforts were rich and, in some cases, surprising. Some things we expected to be painful and important to students, like applying to graduate from the university, were not. Why? Because students (hopefully) only do that once in their academic career. So, while it was painful, that difficulty was not identified by students as important. We also learned that as staff and administrators, our view of the university mirrored organizational structures and did not match how students experience problems and look for solutions. The university is a massive organization, and students are deeply frustrated that we interact with them as if we are 200+ individual organizations that never talk to one another. They are frustrated with inefficient processes that waste their time and take away from what is important to them—their academic efforts and developing as adults. Our mental models did not align, and approaches we might have decided to invest in to improve their experience would have missed the mark.

Strategy #3: Address the needs of the whole student.

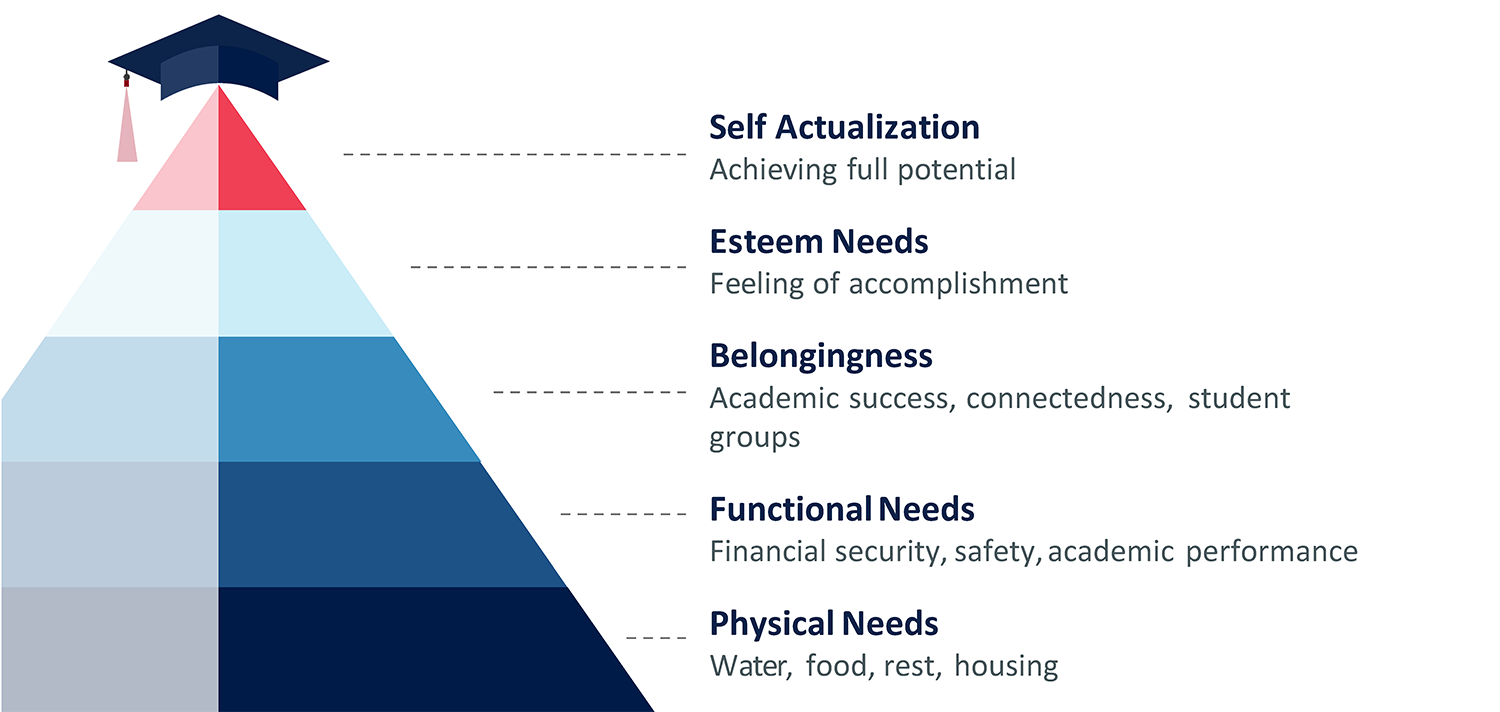

One need not look hard to find a slew of articles about the increase in mental health issues experienced by students today. Pressure to do well academically, increased housing and food insecurities, post–COVID-19 adjustments, social media pressure, and identity politics all add up to a lot of stress for a good portion of our student populations. When developing digital experiences, be intentional and holistic in addressing the needs of the whole student. To help the University of Arizona team on this front, one of our user experience designers adapted Maslow's hierarchy of needs into a student hierarchy of needs (see figure 1). Using this as a framework, the team asked students to map different digital experiences to each layer and is using this analysis to ensure that we deliver digital experiences that address some aspect of each layer over time.

Strategy #4: Buy platforms and leverage their core functionality.

Three platforms play a significant role in students' digital experience:

- Student information system (SIS)

- Learning management system (LMS)

- Constituent relationship management (CRM) system

Each of these platforms offers a set of core business capabilities and performs a finite set of functions well. It is important to understand their strengths and limitations and to use each only for what it does best. For instance, most SIS platforms have communications capabilities that work great for things such as reminders to register or to pay financial aid, but when it comes to non-transactional, bulk communications, CRM platforms are a better option. On the other hand, the SIS excels at transactional processing and complex business rules. Building the right product on the wrong platform is costly. The team at the University of Arizona found this out the hard way in April 2020 when the university desperately needed to roll out an automated way for students to request changes to their schedules in response to the emerging COVID-19 pandemic. We built a new form on our CRM and provided an early, simple version of the product. However, as the requirements for integrating the form into our SIS continued to grow and the underlying business logic expanded, it became clear that building it on our SIS would have been the better choice. Today, we have clearer boundaries on when to use forms for case management on our CRM versus when to build forms with workflow on our SIS. We have also expanded our SIS capabilities with a popular add-on e-forms product that works great when the form is tightly coupled to data and business logic in that system. Workflow is a great example of where scale and complexity play a role in defining the right platform for any given business need.

Strategy #5: Build products for the long term.

I like to say "buy platforms, build products" because platforms have shelf-lives of decades while products have shelf-lives of years. Products are purpose-built to solve a point-in-time problem, and they are built to support not only what the process accomplishes but how it accomplishes it. Over time, I've found that the way someone accomplishes a task can change rapidly, leading to a growing divide between the organization's changing requirements and the product that was purchased. Additionally, many products have overlapping capabilities—bulk communications, as an example—so buying purpose-built products can mean you are paying for a particular capability multiple times. At the University of Arizona, we use a variety of models to build products that weave together data and capabilities across platforms, ranging from full-stack development to the use of low-code platforms. At the same time, we are careful to only invest in costlier approaches (like full-stack development) when it strategically makes sense.

Strategy #6: Unify the user experience with a common design system.

The University of Arizona's student digital experience spans the three major platforms listed above, our native mobile applications, and several custom applications. A digital experience mapping effort conducted in 2019 demonstrated how incredibly disparate the user experience was across these systems and how jarring that experience was for students trying to understand how to complete simple tasks. Today, one strategy unifying the experience is that multiple teams are working in alignment to a common user experience design system that was developed as an expansion of the university's website theme, keeping our public-facing website on-brand. With a common design system developed by a seasoned user experience designer, individual teams can work autonomously toward a common experience and students can move across products more seamlessly.

The University of Arizona is still on its journey to modernize and unify the student digital experience and has begun a similar journey to transform the employee digital experience. Given the speed of technological advances, it is important to acknowledge that there is no final endpoint because expectations will continue to change. Whether your institution is ready to embark on a major transformation effort or is making incremental improvements, these six strategies will enable more strategic use of existing platforms and align resources toward what students (and employees) need most from their technology.

Acknowledgments

I would like to acknowledge the following contributors to the work and artifacts associated with this article:

- Meredith Aronson, Director of CRM and Digital Experience Services, University of Arizona

- Eileen Seegmiller, Principal Business Analyst and Campus Solutions Student Center Product Owner, University of Arizona

- Janet McIllece, Principal Advisor, Higher Education and Digital Strategy, World Wide Technology

- Tim Frank, Senior User Experience Consultant, World Wide Technology

- Patrick Shannon, Senior User Experience Designer, World Wide Technology

Darcy Van Patten is Chief Technology Officer at the University of Arizona.

© 2024 Darcy Van Patten. The content of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY 4.0 International License.