Many institutions may be facing legal action or investigation for accessibility, but proactive investments in staffing, key supports, and leadership buy-in can help mitigate risks.

EDUCAUSE is helping institutional leaders, technology professionals, and other staff address their pressing challenges by sharing existing data and gathering new data from the higher education community. This report is based on an EDUCAUSE QuickPoll. QuickPolls enable us to rapidly gather, analyze, and share input from our community about specific emerging topics.Footnote1

For this QuickPoll on digital accessibility, we partnered with EDUCAUSE's IT Accessibility Community Group and benefited immeasurably from the wisdom and guidance of community group co-leaders Kyle Shachmut and Eudora Struble. We so appreciate their involvement in this important work!

For the purposes of this QuickPoll survey, we offer the following definition of digital or technology accessibility:

Creating and providing online content, services, and technology that can be easily accessed and used by all individuals, including those with disabilities. It means intentionally designing websites, online courses, documents, and materials to support diverse needs, such as by providing captions for videos or descriptions for images and ensuring keyboard accessibility. In this context, accessibility is by design rather than through the accommodation process, which is also vital but which works to make tools and services accessible only after obstacles have been encountered. By prioritizing digital accessibility, higher education institutions can ensure that all students, faculty, and staff have equal access to educational resources and opportunities, promoting inclusivity and enabling everyone to fully participate in the academic community.

The Challenge

Higher education should be available and accessible to all students regardless of physical, sensory, mental, or emotional abilities. Most institutions espouse values and policies that support this ideal, and federal and state regulations help ensure institutional accountability in living up to that ideal. Yet many students, including persons with disabilities, still encounter barriers to full and equitable participation in teaching and learning, and many institutions still have far to go in improving their accessibility services and supports. This QuickPoll report looks at the challenges and opportunities of technology accessibility in higher education, with the hope of offering higher education decision makers and practitioners actionable insights for improving their work in this area.

The Bottom Line

When asked about the consequences of failing to provide accessible technology, the majority of respondents reported risks to their institution in the form of legal action and government investigation, a sobering reality that is made all the more concerning by a relative absence of mandatory staff and faculty accessibility training. While many institutions are making progress in the form of technology accessibility policies and formal plans for improvements to technology accessibility supports, investments in staffing and increased leadership awareness and buy-in will be critical for more meaningful and longer-term success in making higher education more accessible and equitable for all stakeholders.

The Data: Institutional Risk

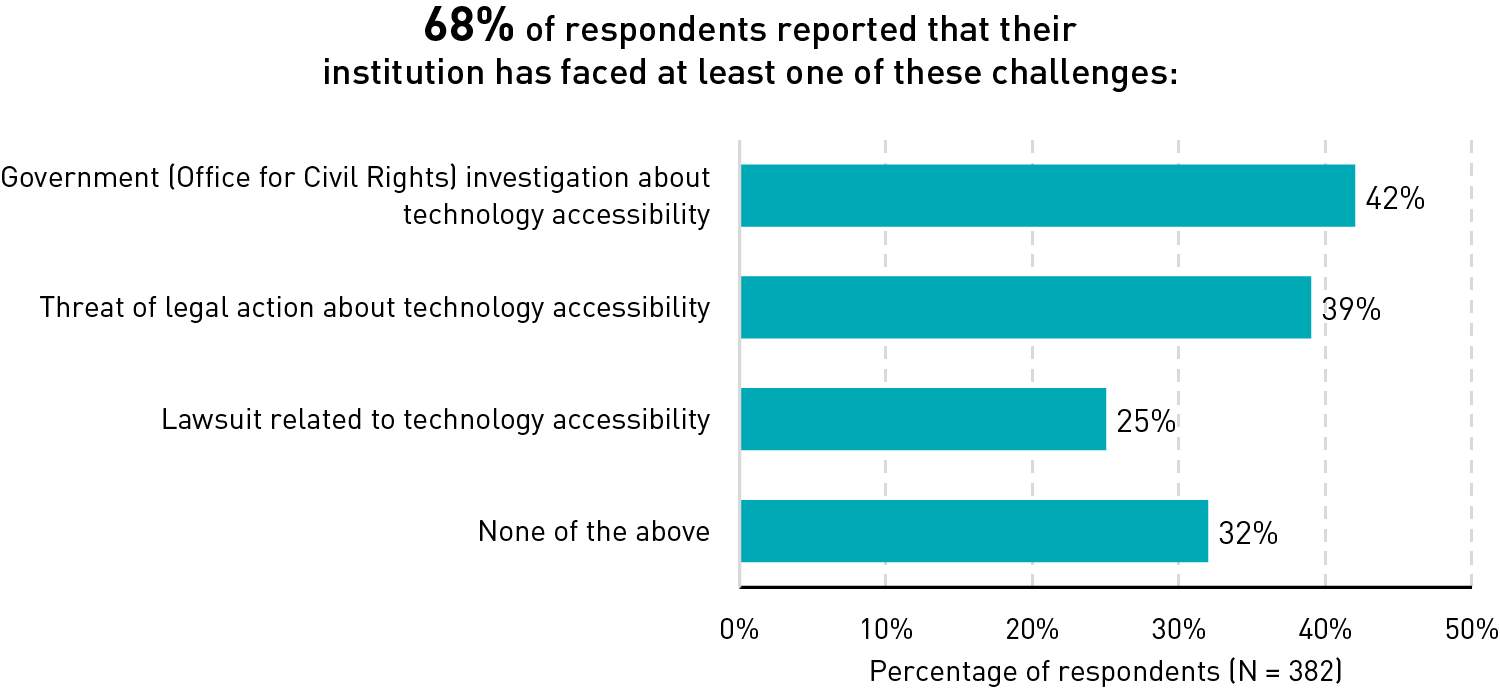

Institutions are facing legal and government challenges, and some are facing multiple challenges. Asked about lawsuits, threats of legal action, or government investigations related to technology accessibility, a full 68% of all respondents reported that their institution has faced at least one of these challenges, with more than a quarter (28%) having faced more than one (figure 1). Only about a third (32%) of respondents said their institution has not experienced any of these challenges.

More risk for larger institutions. Respondents from the largest institutions—those with 15,000 or more students, faculty, and staff—were significantly more likely than other respondents to report facing at least one legal or government challenge related to accessibility, with 79% of these respondents reporting at least one legal or government challenge, compared with 54% of all other respondents. Respondents from the largest institutions were also more likely to report facing more than one of these challenges, perhaps an indication of the greater service demands and operational complexities present at larger institutions.

Institutions are also planning improvements. The silver lining of institutional risk is that improvements appear to be on the roadmap for many of our respondents' institutions. The majority of respondents (76%) reported that their institution has an "official plan" to improve digital accessibility for those who need it. This number is higher among respondents from the largest institutions (82%, compared with 68% among all other respondents), which may be at least in part due to the greater volume of accessibility challenges these institutions are experiencing.

The Data: Institutional Culture and Structure

Institutions are making progress in some key areas. There are bits of good news about the cultures and structures supporting accessibility at colleges and universities. A strong majority of respondents (82%) reported that their institution has a policy about digital accessibility, and 75% reported that their institution's diversity initiative includes considerations of accessibility and persons with disabilities. Asked whether they knew the designated person or office to contact with any accessibility challenges or needs, 86% of respondents answered in the affirmative. In sum, most respondents reported at least a basic awareness of their institution's accessibility values and resources.

A closer look at respondent agreement with a series of statements about accessibility at their institution, however, suggests that familiarity and confidence with accessibility values and requirements is highest in closer proximity to individuals' own work or the work of their teams (table 1). Respondents appear to be highly confident in making their own work or their team's work accessible (83% agreed), while they appear to be far less confident in understanding their institution's general accessibility requirements and goals (63% agreed) and in having the institutional support they need (53% agreed).

|

|

Strongly Disagree or Disagree | Neither Agree nor Disagree | Agree or Strongly Agree |

|---|---|---|---|

|

I know how to make my work and/or my team's work accessible. |

6% |

11% |

83% |

|

I understand my institution's accessibility requirements and goals related to my specific work (or my team's work). |

15% |

13% |

71% |

|

I understand my institution's accessibility requirements and goals. |

21% |

14% |

63% |

|

I have the support I need to make technology accessible at my institution. |

27% |

19% |

53% |

More accessibility staff means more accessibility support. Staffing for accessibility resources and services may be one of the most important supports an institution can offer its stakeholders. A plurality of respondents (42%) reported having one or two staff on their campus with technology accessibility as their primary responsibility, and another 17% reported having no staff with technology accessibility as their primary responsibility. Not surprisingly, respondents from the largest institutions reported having more staff with primary responsibility in technology accessibility. Regardless of institution size, though, the presence of at least some staff dedicated to technology accessibility increases the likelihood that an institution will have a technology accessibility policy in place, offer accessibility training to both staff and faculty, and have official plans in place to make accessibility improvements. In other words, our data show that any institution will benefit in these ways from having staff dedicated to technology accessibility.

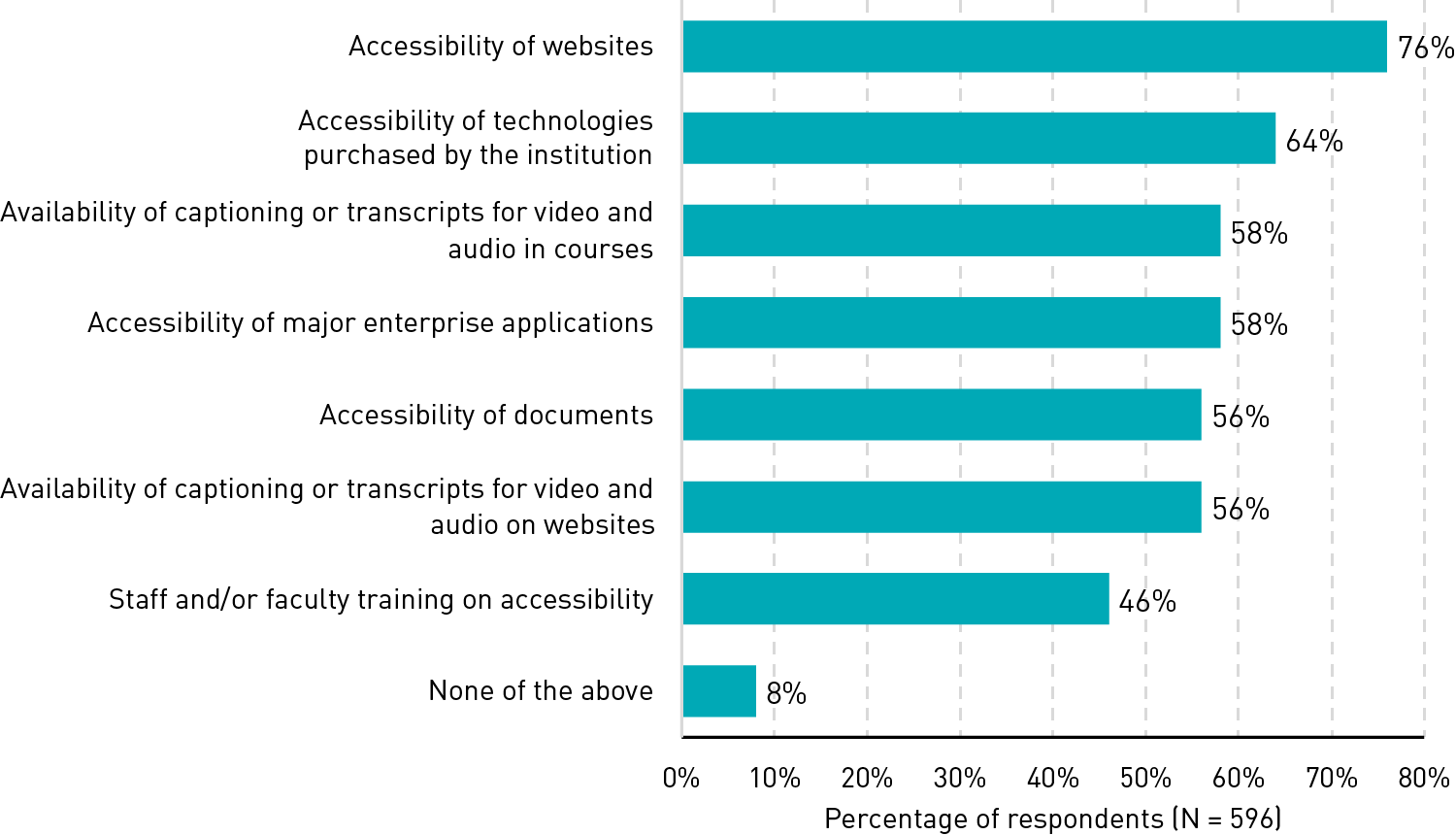

Website accessibility is primary among institutional supports. Institutions with more staff dedicated to accessibility are also more likely to have a number of important accessibility supports in place. When asked to indicate which accessibility supports their institution is regularly assessing and reporting on, a full 76% of respondents selected "accessibility of websites" as the most common institutional support (figure 2). The other supports on our list were selected by the majority of respondents, with the exception of staff and/or faculty training on accessibility, a topic to which we will now turn.

The Data: Staff and Leadership Awareness

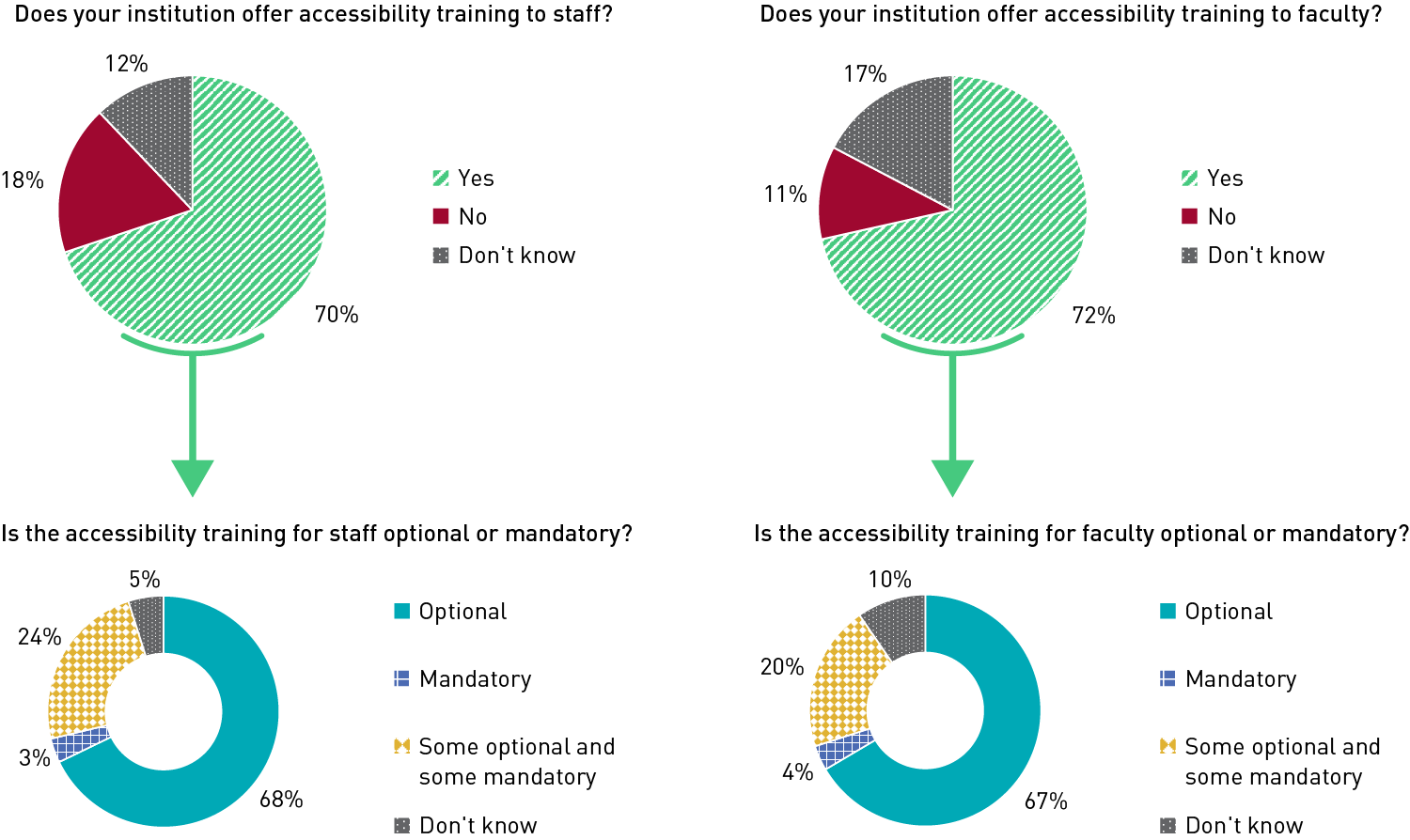

Institutions are offering training, but are staff and faculty participating? Both staff and faculty help shape the accessibility experiences of their students and other institutional stakeholders, and it is encouraging that strong majorities of respondents reported that their institution offers accessibility training to staff (70%) and to faculty (72%) (figure 3). The mere availability of training, though, does not guarantee staff and faculty participation in and use of that training. When asked whether accessibility training is optional or mandatory, the majority of respondents reported that staff and faculty training is only optional (68% for staff training, and 67% for faculty training). Around a quarter of respondents reported that staff and faculty training is a mixture of optional and mandatory (24% for staff, 20% for faculty), and very few respondents reported that training is mandatory for both stakeholder groups.

Open-ended comments from respondents provide evidence that staff and faculty may not be aware of, taking advantage of, or finding value in the accessibility training that is available to them:

Training is ad hoc at the moment. It would be ideal to have it be mandatory for all faculty and staff. Many people aren't aware that they need to design for accessibility, or they don't know where to begin.

Trainings are not mandatory, and faculty participate on a goodwill basis. Some are very committed, while others do not think it is "their job" to make course materials accessible to all students.

Faculty receive little training or incentive to do so.

(Need improvements in) mandatory and regular training and upgrading. There is initial training with some regulation; then it typically dies as a topic until next time the government implements something.

I think our institution could expand its efforts to educate and train staff and faculty on digital accessibility and how to create accessible content. As far as I know, none of our current training is mandatory.

I'm working with Accessibility Services to train faculty in UDL but it's hard to get faculty to come.

Expansion of faculty and staff training. Currently we offer trainings but these are lightly attended and very base level.

Leadership awareness and buy-in may be lagging. Despite the presence of institutional policies and the availability of resources like staff and faculty training, awareness and buy-in at the level of institutional leadership may still be a challenge for professionals supporting accessibility services and initiatives. Asked if the leaders at their institution are knowledgeable about issues related to technology accessibility, a slight majority of respondents (52%) responded that their leaders are not knowledgeable in this area.

Open-ended comments provide some additional nuance here, highlighting aspects of leadership support that may be needed, including leadership prioritization, follow through, and support for funding and staffing:

[We need] clear commitment toward accessibility from senior leadership.

Fiscal support from senior leadership, mandated accessibility training for onboarding new employees, and incentivized continuing accessibility on skills specific to employee role.

Better understanding from leadership, taking it seriously and giving equal weight in decisions of issues like privacy and security, publicly reporting on our progress, hiring staff with expertise, and a shift in mindset from reacting to problems to proactively working on issues.

Leadership accepting responsibility and funding accessibility correctly. We're understaffed and under budget.

We need leadership buy-in through the hiring of a dedicated staff member for accessibility and enforcement of accessibility needs.

Leadership buy-in, budget that includes FTEs and software support, the inclusion of accessibility fundamentals courses in software engineering and digital design courses.

Common Challenges

Support for accessibility may still be more reactive than proactive. Respondents from larger institutions reported having more accessibility staff and resources in place. These respondents also reported experiencing more legal and government accessibility challenges, however, which may in some cases explain the additional staffing and support—as a reaction to an existing issue rather than proactive planning and preparation. Indeed, some respondent comments hinted at this fear of legal or government consequences as the most effective motivator for making accessibility improvements at their institution. One potential indicator of institutional maturity in accessibility support, then, may be the presence of more intrinsic motivation shaped by institutional mission and values and resulting in a more proactive orientation to accessibility.

Support for accessibility may still be more "on paper" than "in practice." Institutions are implementing accessibility policies, offering (mostly optional) accessibility training, and seeking compliance with federal and state accessibility regulations. There is evidence throughout this report, though, that many institutions still have far to go in weaving accessibility into the fabric of their institutional culture and practices. Institutions' commitment to accessibility on paper must also be expressed through actual investments in accessibility staffing, budgets, and technologies; through staff and faculty accountability for providing accessibility services and support; and through clear and consistent communication on the importance of accessibility from the top levels of the institution's leadership.

Promising Practices

Shore up dedicated staff capacity for supporting accessibility services and initiatives. It's a deceptively simple calculation, and yet one that some institutions still seem not to be adding up—that having more accessibility staff leads to more accessibility support. Those respondents reporting more dedicated technology accessibility staff at their institution, regardless of institution size, also reported having more of the necessary resources and supports for effectively addressing their technology accessibility needs and opportunities. Leaders at institutions with no or insufficient staffing in these areas should explore, now, options for coming up to full staff capacity.

Mandate accessibility training for staff, faculty, and students. The majority of respondents reported facing legal and government accessibility challenges at their institution. The majority of respondents also reported that staff and faculty accessibility training was merely optional at their institution. The disconnect between these two institutional realities must be addressed, and institutions should consider feasible and palatable options for making accessibility training a requirement, not only to minimize risks to the institution but, more importantly, to equip staff and faculty to better meet the needs of all students and creating accessible, equitable learning environments.

All QuickPoll results can be found on the EDUCAUSE QuickPolls web page. For more information and analysis about higher education IT research and data, please visit the EDUCAUSE Review EDUCAUSE Research Notes topic channel, as well as the EDUCAUSE Research web page.

Note

- QuickPolls are less formal than EDUCAUSE survey research. They gather data in a single day instead of over several weeks and allow timely reporting of current issues. This poll was conducted from August 14–15, 2023, consisted of 26 questions, and resulted in 736 responses. The poll was distributed by EDUCAUSE staff to EDUCAUSE members via relevant EDUCAUSE Community Groups, and by IT Accessibility Community Group members to the Association on Higher Education and Disability, the Access Technology Higher Education Network, the Virginia Higher Education Accessibility Partners, and the NC Higher Ed Digital Accessibility Collaborative. We are not able to associate responses with specific institutions. Our sample represents a range of institution types and FTE sizes. Jump back to footnote 1 in the text.

Mark McCormack is Senior Director of Research and Insights at EDUCAUSE.

© 2023 Mark McCormack. The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 International License.