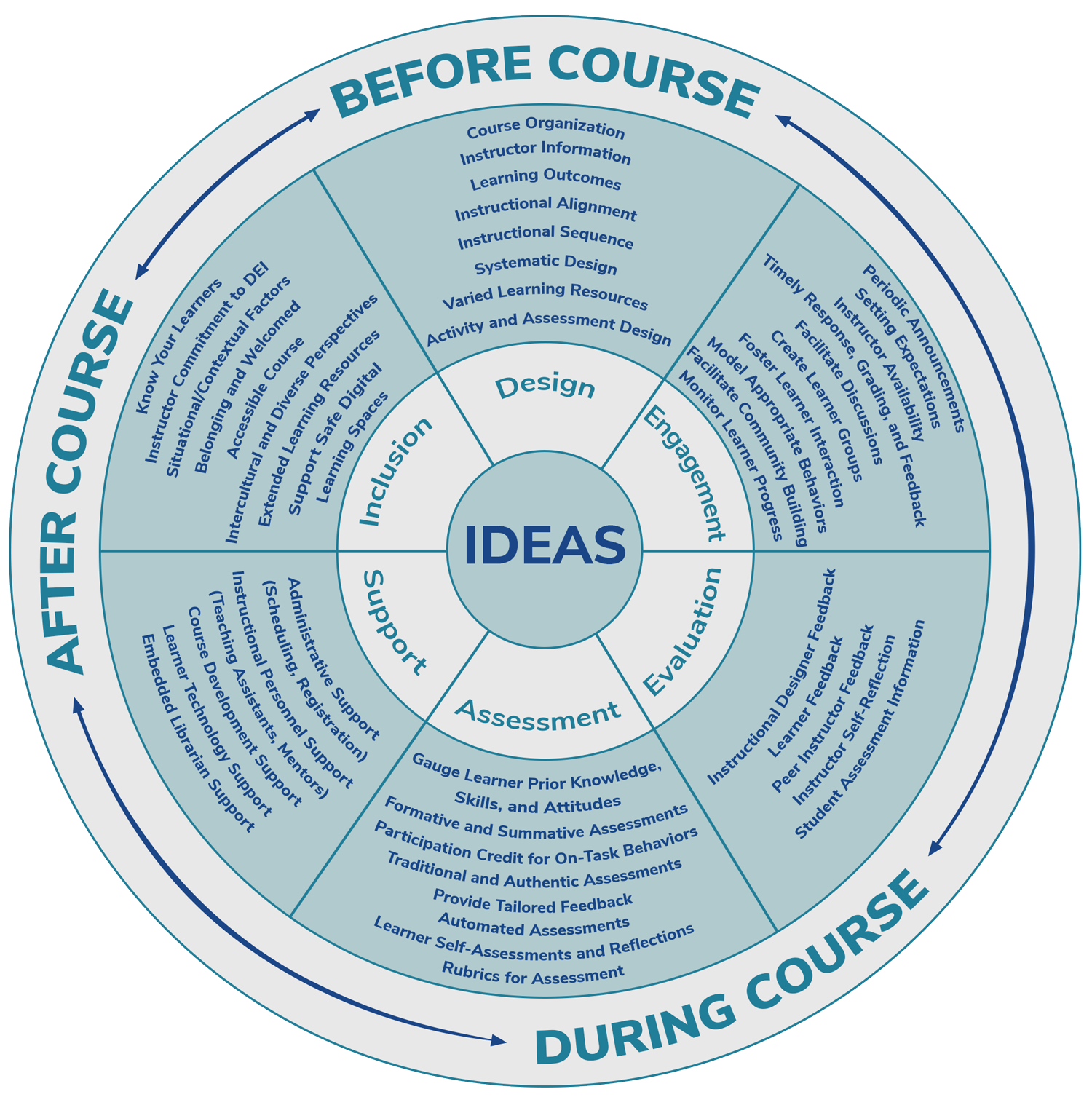

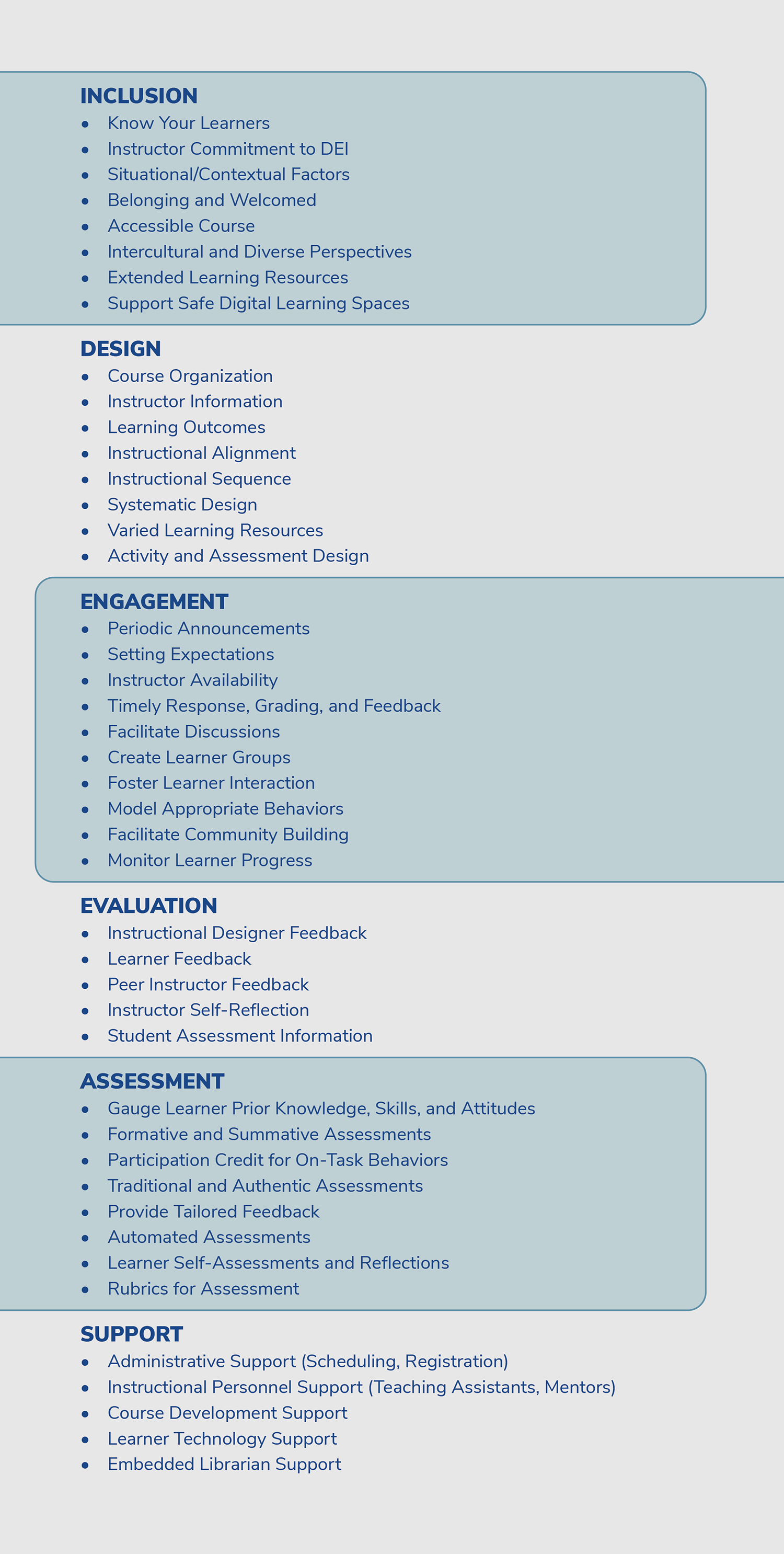

The IDEAS (Inclusion, Design, Engagement, Evaluation, Assessment, and Support) Framework for online teaching and learning highlights best practices for before, during, and after the delivery of an online course to help instructors deliver high-quality courses and improve learner experience and outcomes.

Online teaching and learning is becoming widespread as instructors and students increasingly appreciate the flexibility it offers. A few frameworks help guide online teaching and learning, such as the Quality Matters rubric and the Open SUNY Course Quality Review (OSCQR) Rubric. However, these rubrics focus mainly on the course design aspect. There is still a need for a framework that includes all aspects of online teaching and learning, with a focus on inclusion. This article introduces the IDEAS (Inclusion, Design, Engagement, Evaluation, Assessment, and Support) Framework for online teaching and learning.Footnote1 The framework is intended to provide guidance to online instructors by highlighting several practices established in the research literature for before, during, and after the delivery of an online course.

Framework Design and Expert Review

The IDEAS Framework is based on our years of experience in online teaching and in research into online teaching and learning. Our research experience includes interviewing award-winning online instructors to identify expert practices and also coining the term bichronous online learning to denote the blending of asynchronous and synchronous online learning.Footnote2 After reviewing the current literature, prior research, and teaching and learning practices, we drafted an initial list of twenty-nine IDEAS elements for online teaching and learning. We then contacted seven experts in online teaching and research and invited them to participate in virtual thirty-minute meetings to discuss these elements. Through the meetings, we collected and integrated their feedback. The result is the final list of forty-four IDEAS elements, categorized into six dimensions (see figure 1, below, and table 1, at the end of this article).

The six dimensions of the IDEAS Framework are interrelated, and instructional decisions in one dimension will potentially influence others. For example, the dimensions of both Assessment and Evaluation are interrelated in that assessment data can also be used for formative or summative evaluation purposes; hence, instructors' decisions to employ various practices can influence subsequent instructional decisions. Further, the elements are noted practices in online teaching and learning research literature; however, not all of the practices are necessarily deployed or needed in the same online course. In all cases, instructional goals and student learning outcomes for an online course should influence how instructors choose to deploy their online teaching.

Description of IDEAS Elements

Inclusion

Inclusion refers to providing opportunities to ensure that all learners feel they are welcomed and belong in the course. One of the important aspects of delivering an inclusive online course is for instructors to express their commitment to diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) and to get to know their learners by allowing students to share needs and preferences.Footnote3 Instructors should examine their own assumptions and expectations about learners' behavior and performance and affirm their commitment to each learner's ability to learn online. Instructors can participate in professional development on DEIFootnote4 and include a DEI statement in the syllabus, as well as review the syllabus to make the course equitable. They should be mindful of their learners' situational and contextual factors to ensure that their learners have access to necessary devices and reliable internet connection.Footnote5 Additionally, instructors must support learners who require specialized instruction and related services, including extended learning resources. Instructional material must be offered from diverse perspectives and must be designed and delivered to meet the needs of learners with cognitive and physical disabilities. When instructors are committed to DEI efforts, they work to handle online class dynamics that may perpetuate systemic inequities, and they support learners to create and facilitate safe digital learning spaces.

Design

Design focuses on incorporating instructional materials, activities, resources, and assessments that are aligned to learning outcomes. Course information must be organized and chunked into manageable segments, such as through modules or units.Footnote6 In an instructor-led course, learners should be provided with the instructor's contact information early in the course so that they can connect with the instructor through multiple ways. In addition, researchers emphasize the importance of aligning course content and activities to achieve objectives and sequencing activities to maximize learning.Footnote7 The framework emphasizes including content and learning activities to help achieve stated course learning outcomes and providing opportunities to engage learners through learner-learner, learner-instructor, and learner-content interaction.Footnote8 This interaction can assist in building a sense of community.Footnote9 Community can also be achieved by humanizing online courses through using videos and group work that provides learners with opportunities to interact.Footnote10 A variety of learning resources can be included in the course: assigned textbook readings, web resources, and videos, for example. With careful design of formative and summative activities and assessments (e.g., discussions, projects, papers, presentations, quizzes, exams) and their inclusion throughout the course, the learning outcomes can be achieved.

Engagement

Engagement focuses on the instructor promoting learner interactions and facilitating meaningful community building. The instructor can engage the learner by setting the expectations for the course early. The instructor can send periodic announcements to establish the instructor's presence and availability and to explain how the learner can reach the instructor online. Instructors should engage in various facilitation strategies using timely communication, providing quality feedback,Footnote11 and guiding the students to navigate the course successfully. The instructor facilitates learner engagement through discussions and group activities both asynchronously and synchronously online by using various digital tools, including the learning management system and synchronous tools. This engagement facilitates learner interaction and assists students in building communities by establishing relationships and supporting each other. In addition, several strategies can be used to engage the online learner by enhancing learner-learner, learner-instructor, and learner-content interaction.Footnote12

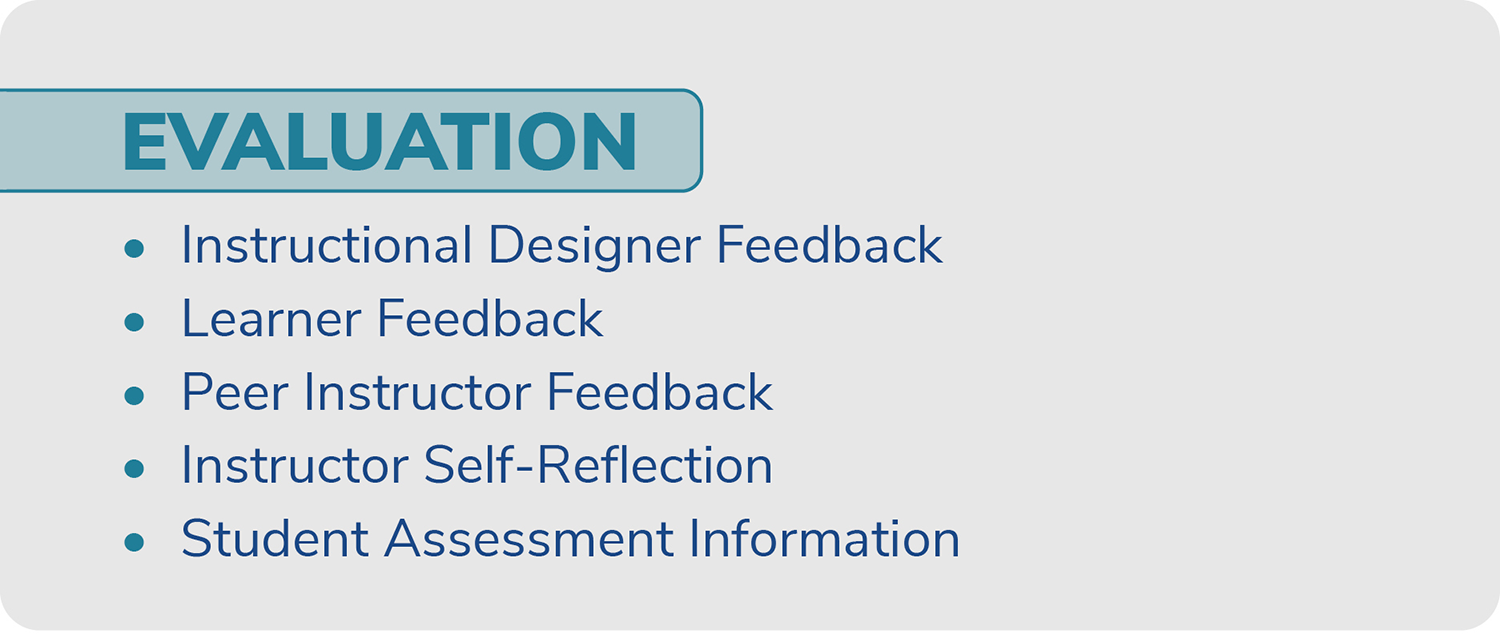

Evaluation

Evaluation emphasizes the importance of assessing the online course using a variety of strategies and identifying areas for improvement. This dimension focuses on using different methods to assess course effectiveness. Evaluation is a critical aspect of teaching, and online courses can be evaluated using various strategies. A variety of personnel (instructors, students, designers, and administrators) can be involved in evaluating the course periodically through online course evaluations, learner completion rates, satisfaction surveys, peer review, instructor and learner feedback, content and learning analytics, and learner performance.Footnote13 Evaluation of instructional content can also occur before the course is taught, working with an instructional designer to review and evaluate the content. During the implementation, learner feedback can be collected early in the course, during the course, and at the end of the course. Peers can be invited to review the course and provide feedback. And finally, the instructor can self-reflect during the course and at the end of the course to identify areas that can be improved the next time it is taught. Overall, evaluation is a critical step to support learning effectiveness by ensuring a continuous process of improvement.

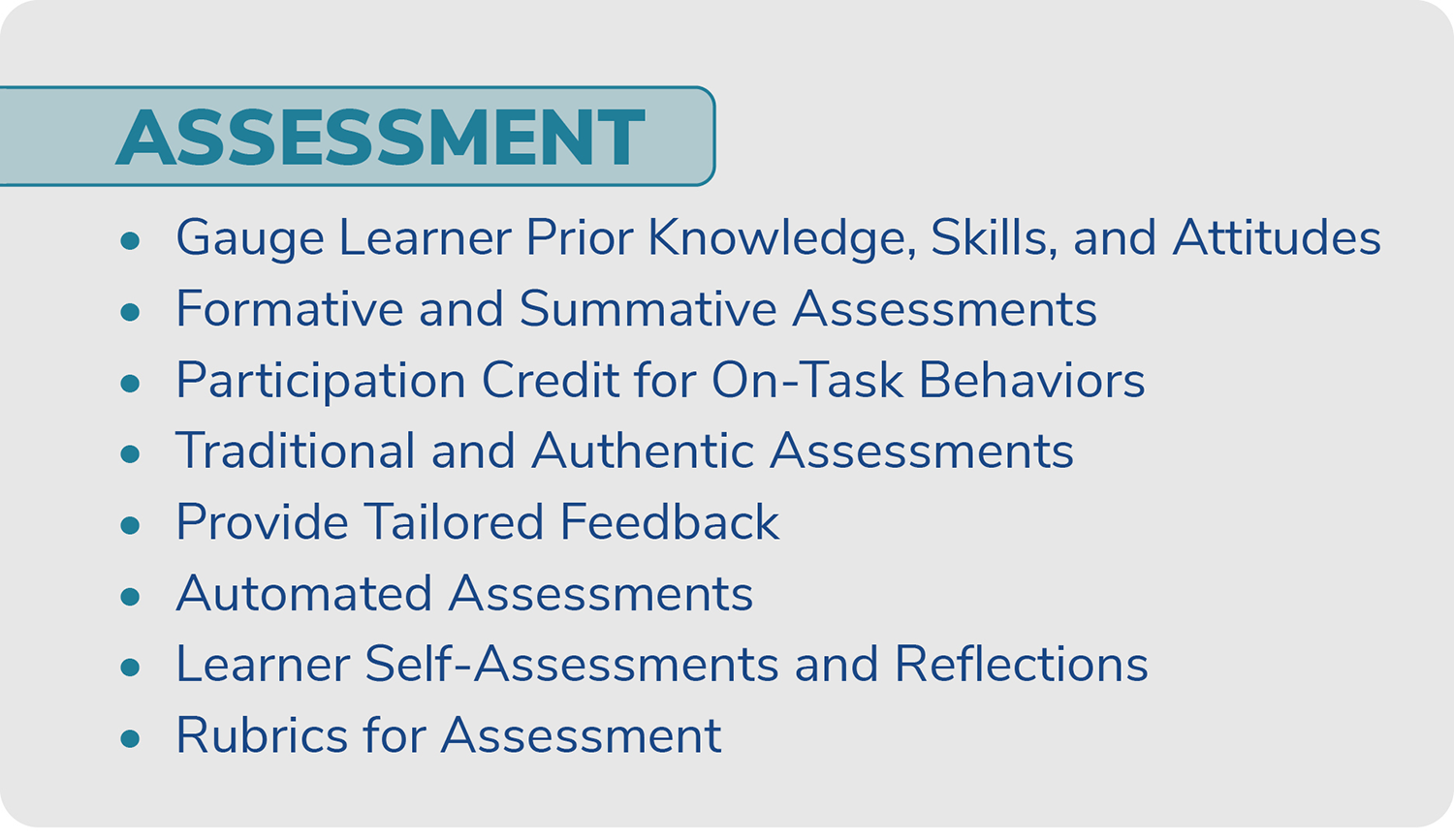

Assessment

Assessment focuses on gauging the learners' progress in the course by measuring the achievement of the learning outcomes. Instructional design processes emphasize the importance of aligning assessments with instructional objectives and instructional material.Footnote14 It is critical that instructors gauge the learners' prior knowledge, skills, and attitudes at the beginning of the course and continuously monitor progress during the course. An online course can include a combination of assessment techniques, such as traditional assessment methods (e.g., multiple choice quizzes or exams) or those labeled as authentic assessment methods (e.g., e-portfolios, online journals, or group work).Footnote15 Learners can also be provided credit for activities such as participating in synchronous sessions or completing optional activities. Researchers have also stated the importance of assessments occurring throughout the course, so that students have the opportunity to periodically understand their learning progress and provide feedback on the assessments.Footnote16 Automated assessments can be used to provide feedback to learners more quickly. Including rubrics that clearly state what is expected of the learners is helpful in an online course. Rubrics assist the instructors by saving time spent grading, providing effective feedback, and promoting student learning.Footnote17 Online courses are recommended to include self-assessment for learners, which is helpful for self-monitoring and reflecting on their learning.

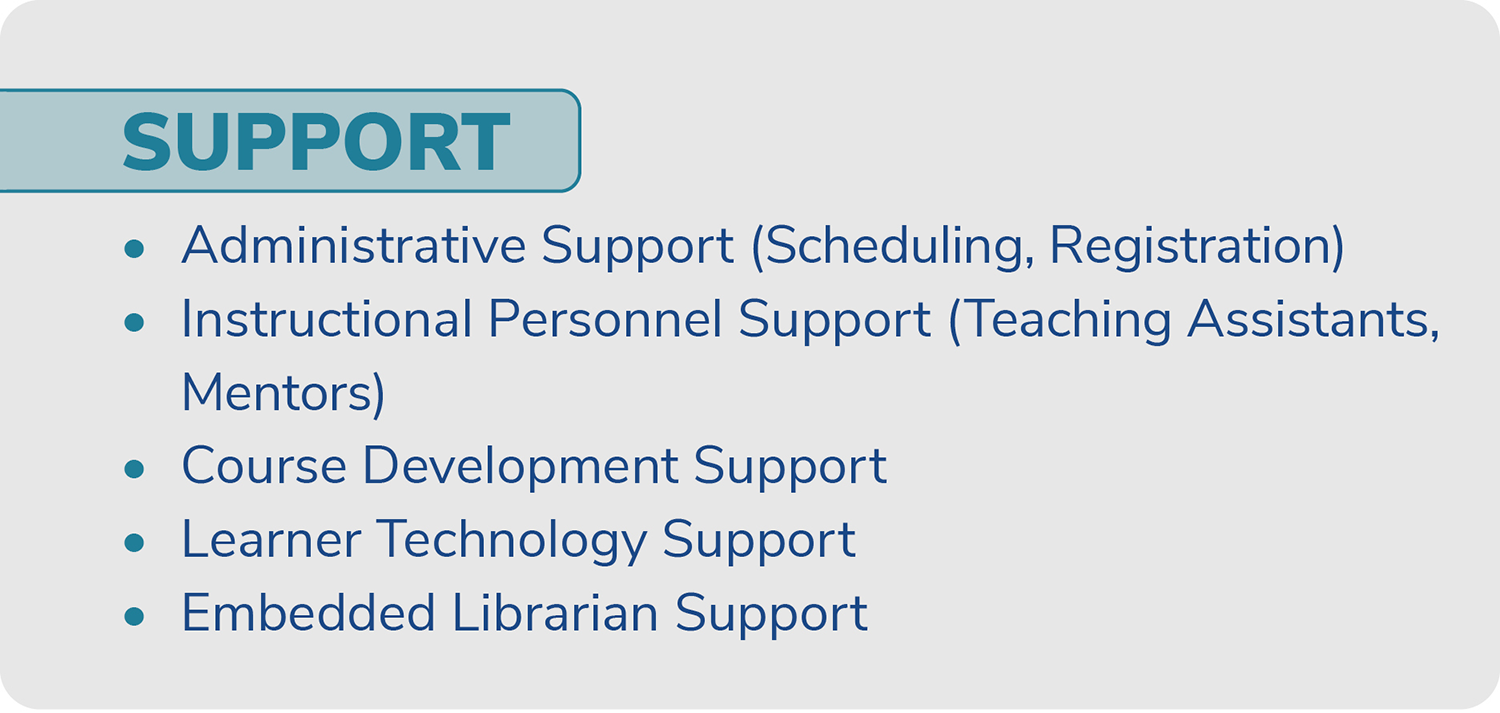

Support

Support is essential for both instructors and learners throughout the teaching and learning process. When instructors have full teaching loads, finding the time needed to prepare and create an effective online course can be challenging. Instructors should be given additional course development time to design the course at least a semester before it is delivered. In addition, providing professional development opportunities for instructors to develop effective online courses is essential. Since teaching online is considered time-consuming, instructional personnel support—such as teaching assistants and mentors—is helpful. Peer mentors can provide guidance on how to be effective with online design and facilitation and provide their mentees with a model of best practices. This not only benefits the faculty member who is new to teaching online but also provides job satisfaction and instructor success for the mentors.Footnote18 Teaching assistants are especially helpful in supporting large online courses and in facilitating discussions.Footnote19 Course development and technology support for hardware and software is also essential for instructors who teach online. Online teaching requires different competencies, and hence opportunities to work with instructional designers or attend professional development will provide instructors with the support to learn how to develop effective courses and integrate a number of technologies to achieve the desired outcomes. In addition, instructors also prefer just-in-time technology support and help desk access. More organizations are beginning to set up twenty-four-hour access for faculty and students to provide support on technical issues, such as questions related to the learning management systems. Finally, embedded librarian support is helpful for the online instructor and students.

Conclusion

The IDEAS framework is intended to assist online instructors in the full lifecycle of an online course: before, during, and after the course. While the six dimensions of Inclusion, Design, Engagement, Evaluation, Assessment, and Support may not fully capture all the nuances of online teaching and learning, the IDEAS Framework does provide a strong starting point that extends beyond the online course design features common in other frameworks. We hope the IDEAS Framework can be further developed by researchers in the online learning community to push the research agenda forward in the field. And we expect that the framework will evolve as we gain more insights into the complex craft of online teaching and learning.

Notes

- This is not the exact acronym, of course. We represented the two words Engagement and Evaluation with one "E" for IDEAS. Jump back to footnote 1 in the text.

- Florence Martin et al., "Award-Winning Faculty Online Teaching Practices: Course Design, Assessment and Evaluation, and Facilitation," The Internet and Higher Education 42 (2019); Florence Martin, Drew Polly, and Albert Ritzhaupt, "Bichronous Online Learning: Blending Asynchronous and Synchronous Online Learning," EDUCAUSE Review, September 8, 2020. Jump back to footnote 2 in the text.

- James D. Basham et al., Equity Matters: Digital and Online Learning for Students with Disabilities, report (Lawrence, KS: Center on Online Learning and Students with Disabilities, 2015). Jump back to footnote 3 in the text.

- Kristine S. Lewis Grant and Vera J. Lee, "Wrestling With Issues of Diversity in Online Courses," Qualitative Report, no. 19 (2014). Jump back to footnote 4 in the text.

- Debra R. Comer, Janet A. Lenaghan, and Kaushik Sengupta, "Factors That Affect Students' Capacity to Fulfill the Role of Online Learner," Journal of Education for Business, 90, no. 3 (2015). Jump back to footnote 5 in the text.

- Susan Ko and Steve Rossen, Teaching Online: A Practical Guide, 4th ed. (New York: Routledge, 2017); Suzanne Young, "Student Views of Effective Online Teaching in Higher Education," American Journal of Distance Education 20, no. 2 (2010). Jump back to footnote 6 in the text.

- Betul C. Czerkawski and Eugene W. Lyman III, "An Instructional Design Framework for Fostering Student Engagement in Online Learning Environments," TechTrends 60 (2016). Jump back to footnote 7 in the text.

- Michael G. Moore "Editorial: Three Types of Interaction," American Journal of Distance Education 3, no. 2 (1989). Jump back to footnote 8 in the text.

- Nuan Luo, Mingli Zhang, and Dan Qi, "Effects of Different Interactions on Students' Sense of Community in E-Learning Environment." Computers & Education 115 (2017). Jump back to footnote 9 in the text.

- Xiaojing Liu et al., "Does Sense of Community Matter? An Examination of Participants' Perceptions of Building Learning Communities in Online Courses," Quarterly Review of Distance Education 8, no. 1 (2007). Jump back to footnote 10 in the text.

- Florence Martin, Chuang Wang, and Ayesha Sadaf, "Student Perception of Helpfulness of Facilitation Strategies That Enhance Instructor Presence, Connectedness, Engagement and Learning in Online Courses," The Internet and Higher Education 37 (April 2018). Jump back to footnote 11 in the text.

- Florence Martin and Doris U. Bolliger "Engagement Matters: Student Perceptions on the Importance of Engagement Strategies in the Online Learning Environment," Online Learning 221, no. 1 (2018). Jump back to footnote 12 in the text.

- Martin et al., "Award-Winning Faculty Online Teaching Practices." Jump back to footnote 13 in the text.

- Walter Dick, "The Dick and Carey Model: Will It Survive the Decade?" Educational Technology Research and Development 44, no. 3 (1996). Jump back to footnote 14 in the text.

- Martin et al., "Award-Winning Faculty Online Teaching Practices." Jump back to footnote 15 in the text.

- Jorge Gaytan and Beryl McEwen, "Effective Online Instructional and Assessment Strategies," American Journal of Distance Education 21, no. 3 (2007). Jump back to footnote 16 in the text.

- Dannelle D. Stevens and Antonia J. Levi, Introduction to Rubrics: An Assessment Tool to Save Grading Time, Convey Effective Feedback, and Promote Student Learning (Sterling, VA: Stylus, 2013). Jump back to footnote 17 in the text.

- Laura G Lunsford, Vicki Baker, and Meghan Pifer, "Faculty Mentoring Faculty: Career Stages, Relationship Quality, and Job Satisfaction," International Journal of Mentoring and Coaching in Education 7, no. 2 (2018); Alan G. Wasserstein, D. Alex Quistberg, and Judy A. Shea, "Mentoring at the University of Pennsylvania: Results of a Faculty Survey," Journal of General Internal Medicine 22 (2007). Jump back to footnote 18 in the text.

- Ya-Ting C. Yang, "A Catalyst for Teaching Critical Thinking in a Large University Class in Taiwan: Asynchronous Online Discussions with the Facilitation of Teaching Assistants," Educational Technology Research and Development 56 no. 3 (2008). Jump back to footnote 19 in the text.

Florence Martin is Professor of Learning, Design, and Technology at North Carolina State University.

Albert Ritzhaupt is Professor of Educational Technology and Computer Science Education at the University of Florida.

© 2023 Florence Martin and Albert Ritzhaupt. The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0 International License.