Nine questions can help demystify organizational culture, making it an ally in data governance initiatives.

Establishing an effective data governance program remains a significant challenge for many institutions of higher education. For any institution, determining the optimal conditions under which data governance will be adopted, valued, and leveraged remains a considerable challenge for most data professionals. Many begin by investing time and effort into developing a data governance charter, identifying council or committee members, debating whether to explore homegrown or vendor solutions, and deliberating what business units to focus on first. Most, however, miss a vital component to succeeding with any data governance initiative: culture. Culture is everywhere all at once, and Peter Drucker is famously attributed with saying "Culture eats strategy for breakfast." Yet data professionals continue to spend significant time focusing on strategy alone. Danette McGilvray, too, warns data professionals:

"Culture and environment impact all aspects of your information quality work. They should inform all your data quality work, but often they are not intentionally considered.… [Y]ou will better accomplish your goals if you understand and can work effectively with the culture and environment of your company."Footnote1

We strongly agree with Drucker and McGilvray and argue that taking the time to understand the culture of your institution is a powerful foundation upon which to build your data strategy.

Why Culture Matters to Data Governance Work

We recognize that a void exists in terms of culture-based data governance guidance. Others have written extensively on data governance from a technical or functional sense, but few have explored how culture could and should be analyzed to promote a mature, data-governed ecosystem. We are optimistic that in this article, you will find a helpful roadmap to aid you in adding a culture-based approach to your leadership toolbox.

Culture is difficult to singularly define but generally includes several elements:

- Shared beliefs

- Values

- Artistic expression

- Symbols

- Artifacts

- History

- Common language

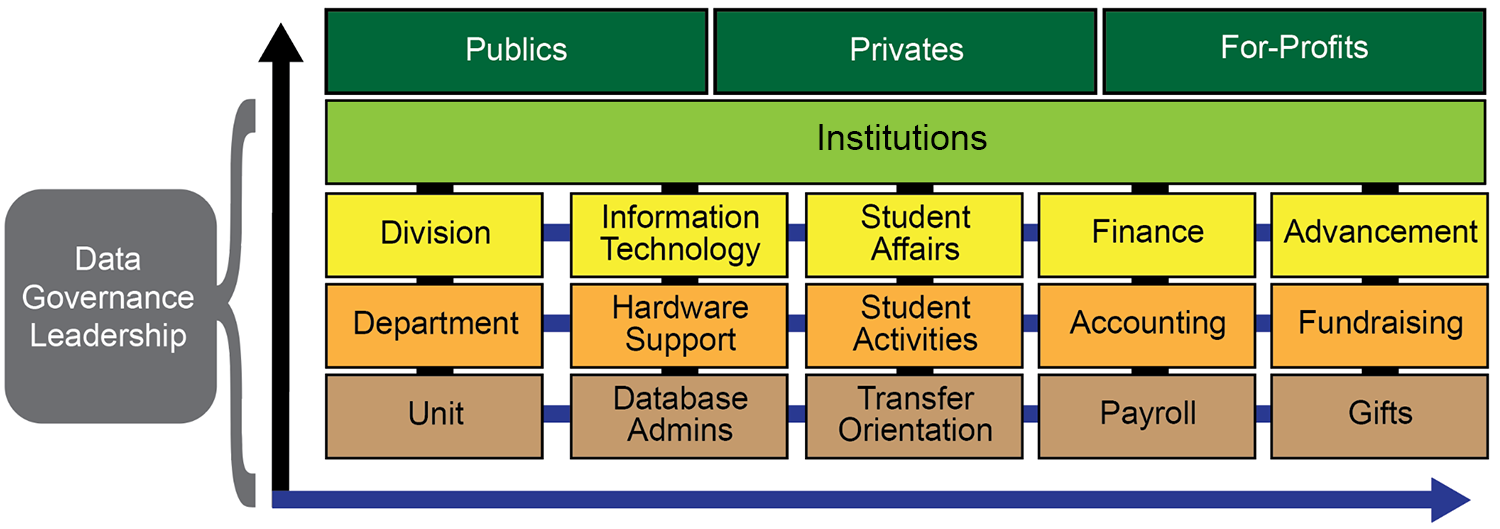

Whereas some elements of culture are tangible, most are not and are better understood through observation and/or experience. Additionally, cultures don't have boundaries, and they overlap and inadvertently mix with various other cultures. In the context of higher education, Robert Birnbaum argues that colleges and universities consist of many interconnected, closed-loop systems.Footnote2 As such, each division, department, and unit exhibits a particular culture while also being a part of a much larger institutional culture (see figure 1). As such, an institutional culture consists of many discrete component-level cultures that overlap vertically and laterally while exerting its own cultural imprint on each component. This web-like interconnection of cultures complicates our task to make sense of these distinct but linked realities. Still, this recognition requires data governance leaders to consider culture using a holistic rather than a singular perspective.

It is important to underscore that like people, institutions of higher education are unique. No two are identical. In addition to the common elements of culture listed above, differences in aspects such as size, location, mission, degree offerings, research specialization, student-body composition, and budget all result in a tapestry of diverse entities. Applying a cultural lens when building your data governance program requires you to resist a one-size-fits-all approach. It just won't work! Instead, taking the time to understand and leverage the unique cultural conditions of your institution will improve your odds of implementing a successful data governance program and strategy.

Finally, building a data governance program, which undergirds institutions' analytics programs, is not a solo adventure (or for the faint of heart). EDUCAUSE, AIR, and NACUBO emphasized this and five other guiding principles in their Joint Statement on Analytics, which insists that analytics is a "team sport" that requires immediate action. Recently, EDUCAUSE convened an expert panel (of which we both were participants) to discuss the future of data governance in higher education and to assist in developing the 2023 EDUCAUSE Horizon Action Plan: Data Governance to serve as an action guide for the 2022 EDUCAUSE Horizon Report: Data and Analytics Edition.Footnote3 Each publication details the need to transform culture.

Making Sense of Your Institutional Culture

Culture is like art—you know it when you see it. And yet, what practical, culture-focused guidance can information technologists, institutional researchers, and other practitioners use to advance their data governance efforts? We offer nine critical questions below that could supercharge data governance efforts at your college or university. We encourage you to consider using the "Get Started" tips included for each question. Adapt, modify, or apply these tips in ways that you believe will resonate with your own institutional stakeholders.

1. How do you make sense of your culture?

Because culture tends to be opaque, it can be very challenging for new employees to onboard successfully if they don't invest time in attempting to make sense of the culture of their new workplace. The same could be said for understanding the culture surrounding new initiatives, such as implementing or enhancing data governance practices. At its core, making sense of the impact of culture on your work, first and foremost, requires an acknowledgment that culture exists and that it has real and tangible impacts on your work.

With the cultural-impact premise now on your radar, the next logical step is to make sense of numerous institutional inputs. An important set of inputs concerns external reputation. By taking time to consider the impact of how the public perceives your institution—through educational rankings, reputation, endowment support, and other means—you gain the ability to align your observations of your institution's culture with how others perceive your institution. Additionally, another key input is your institution's approach to teaching, research, and service (indicated by your Carnegie Classification designation) and how this mission impacts project prioritization and established goals. These inputs have a direct bearing on your ability to link data governance efforts with macro-institutional priorities.

Get started with these three practical steps to enhance your ability to make sense of how the public views your culture:

- Seek out and speak with colleagues from institutions of similar Carnegie Classifications. Doing so lets you evaluate best practices from institutions that share core values and goals. Being intentional and asking about their culture in addition to their practice provides you with the added benefit of being able to evaluate how your institution might respond to any new ideas you hear.

- Consider how data and institutional outcomes are shared with donors and corporate partners. What is the culture saying about itself in these metrics? Furthermore, are these data governed and managed, given their important linkage to financial support? Does this represent another selling point for your work?

- Leverage artificial intelligence / natural language processing to conduct a macro review of independent news stories, publications, or articles written about your institution. What themes emerge, and how do these themes inform what your community believes about your institution? Using this information, consider how you might position data governance practices to help the institution redefine its position in the community using trusted and secured information. We all know that public confidence in higher education is waning, so how might an intentional data-first strategy combat these concerns and, by extension, promote better data governance adoption?

2. In what ways is your culture expressed implicitly, requiring one to listen carefully?

In your day-to-day work life, you are bombarded with opportunities to observe your institution's culture. A culture-competent leader listens for cues and secondary intent in every interaction. How one actively reflects and listens to not only what is said but, more importantly, what is not said increases the odds of using culture successfully to advance (data) strategies. Knowing what cultural issues are off base or nonstarters can eliminate wasted effort and time fighting for elements of change that, no matter how effective you might be, will never get off the ground. Equally important is developing the skill to decode your institution's unstated culture, found hidden between the intent of a message and the signals it sends to the community. Reading for content and paying attention to word choices provides the clues needed to go one level deeper into thinking about how a communication either supports or differs from the established culture on campus.

Typically, cultural signs can be found in public forum presentations, institutional communications, committee meetings, and even agendas and minutes. The way others discuss and identify cases in which campus culture has prevented something from succeeding is a clear and obvious clue for a culture-savvy leader to note. Developing the skill of active listening while advocating for data governance initiatives is of vital importance.

Get started with these three practical steps to enhance your ability to listen for cultural cues:

- Nicole Lowenbraun, content director at Duarte, explains that active listening, or being a good listener, is more than just not speaking when someone else is talking. Instead, consider what your conversation partner needs from you. What are they really asking of you? Lowenbraun uses the mnemonic SAID as a way to remind readers that in most settings others seek us to aid them in one of the following ways: Support, Advance, Immerse, or Discern.Footnote4 Next time you find yourself in a conversation, pause and ask yourself which of these four approaches does the other need? What does this tell you about your institutional culture? Your role within the culture?

- If you are new to your institution, search the Wayback Machine for your institution's website to look up previously released communications and updates about important campus events, initiatives, and responses. With this tool, you can, in essence, become a cultural time traveler. Be attentive to comparing how your institution's culture may have shifted over time.

- Careful listening also requires conversations about the history of data governance at your institution. Reach out to colleagues in institutional research, information technology, the registrar's office, finance, human resources, and others to gain a better understanding. A culture-focused leader knows to carve out time every week to interact with partners/stakeholders to understand the past as well as the present.

3. Is your culture explicit and easy to observe?

Just as traveling abroad teaches you more about your own culture (because the differences become more apparent from a distance), the experience of being in a new location requires you to pay attention and navigate your surroundings. This skill should be used not only abroad but also within your institution. A culture-focused data leader should be able to observe and decode what they hear and also what they see or read. Hone your ability to identify those in your community who not only talk the talk but walk the walk. Looking for partners whose behaviors build trust makes the job of implementing data governance easier.

An excellent place to start is the institution's strategic plan. Who leads planning? What areas do they focus on? How do these priorities interact with your charge of improving data governance? Do you see a role for your work to support these macro-sized initiatives? Other spaces to make observations: celebrations, out-of-the-box practices, and how community members treat one another (does communication exist among equals only or across the typical boundaries between faculty, staff, and administration?). Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, look for the hidden patterns of who is invited to meetings (and who is not), as well as who is aware of decisions before they are publicly announced. Identifying the factors leading to these behaviors may give you additional clues about the culture of your campus.

Get started with these three practical steps to enhance your ability to observe culture:

- Be sure to always look at the appendices of reports, strategic plans, and other formal documents to see who was engaged and involved in the process. Was the process representative of your larger culture or selected individuals? These influencers might be important allies in your data governance effort. Reach out to ask for some time (and be patient if it takes a few weeks!).

- Pay attention to visual clues and body language of the participants in meetings. Gravitate toward potential partners whose facial expressions, gestures, and posture indicate to you they may be supportive of your work.

- If you were to conduct an assessment of the various divisions within your institution, how would you grade them on visible examples of positive change? Where is openness to change welcomed? When starting your data governance efforts, invest your time in units or divisions where it may be more likely to be embraced.

4. How is your culture impacting your communications within the community?

The ability to voice one's ideas or concerns within an institution, as well as asking questions and admitting to making a mistake without the fear of pushback, is known as psychological safety.Footnote5 Interpersonal interactions train you to understand what others expect (or don't expect) regarding your behavior and speech content. Frequently we are not aware of the signals we're sending to another about the "communication rules." Yet each institution of higher education has its own cultural norms of how people speak and interact with one another. Does your institution's culture favor those who speak directly or those who speak indirectly? Face-to-face or via a proxy? Are there different expectations when speaking to people who occupy the same or different roles from yours? Does conversational speech differ from written communication? Additionally, who is asked for input and at what stage in a process?

Emails and conversations are the best place to start to glean information. Are emails short and to the point or lengthy and formal? Are certain things said versus not said to people in different roles (i.e., are leaders or middle management told of difficulties)? Who is asked for their input (subject-matter experts [SMEs] or others)? Does leadership speak directly to the community or via channels that allow information to eventually make its way to the various units? Understanding the parameters of speech—how, when, and to whom, as well as from whom—will help the culturally sensitive leader navigate the waters of situating and communicating your data governance efforts and strategy.

Get started with these three practical steps to develop your communication skills:

- As mentioned earlier, building a data governance program is not for the faint of heart. Difficult conversations will need to take place. Read Fierce Conversations by Susan Scott and determine how best to translate Scott's powerful recommendations for interrogating reality at your institution.Footnote6

- At your next meeting, observe those at the table. Do they report on information gleaned from reports, or is the SME included in the discussion? This will provide insight into how your culture is structured regarding messaging delivery and will guide you in shaping how best to convey your strategy and accompanying communication plan.

- During your next meeting (or when reviewing a report), observe whether the level of detail needed is shared with the intended audience. Do leaders ask for detailed information, or is information primarily at a higher, conceptual level? What sort of information is sought by those within a given role? Using this as a guide will enable you to know your audience and to effectively streamline your message.

5. How do institutional leaders express feelings and beliefs about culture?

Because culture is often fluid and sits below the surface, data governance leaders must refine their abilities to make the invisible visible. Understanding where to look for insights about how your organization's culture is expressed doesn't have to be a challenge. A culture-first data governance leader leverages these expressions to help guide the work. Behaving in a manner that is aligned with the overarching institutional culture is a quicker path to success than fighting against it. Leaders who excel in this regard understand the relationship between how others communicate or share opinions about their institution's culture and the ability to leverage these sentiments for success.

Some areas to identify these clues include paying attention to how others evaluate the institution by comparing their experience against that of peers. How does the experience of peer institutions shine a light on areas of challenge and opportunity? What is the basis for identifying a particular institution as a peer, and what does that symbolize? An additional area of focus is external communications. How does your culture seep into these various communication channels? What themes or messages are most often conveyed to those outside your institutional culture? How do officials at your institution describe it to outsiders? Think about your institution's brand, both formally as expressed to others and informally as discussed by those in the trenches. Beyond official, external communications, how do leaders on campus express culture through social media posts and in online forums? Focusing specifically on data, how do members of the community express their feelings and beliefs about data quality, data veracity, ease of consuming/using data, and so on? What strategies are put in place to allow data governance leaders a chance to hear these thoughts in a constructive way?

Get started with these three practical steps to leverage others' feelings and beliefs about your institution's culture:

- Intentionally catalog all institutional communications over a given month. Be sure to scrape any and all communications that are disseminated. After the month, read through the communications and ask yourself, what is being communicated or expressed about culture? Gather an additional set of communications and ascertain whether the pattern is consistent. Better yet, copy and paste all of the text into a document, remove any names of people or units or other sensitive data, and process through ChatGPT to identify qualitative themes related to culture.

- Review your institution's main pages for faculty and staff recruiting. How does the institution position itself as an employer? What cultural undercurrents are present? Next, compare this to your institution's viewbook for prospective students. Do you see congruence? If differences exist, ask yourself why.

- Intentionally communicate about data governance efforts using words, phrases, and examples that are specific to your campus culture. Explain to constituents why your proposals and tasks are relevant to the organization by rooting them in previously shared observations by the institution.

6. How does your culture influence leaders' ability to be confident in their decisions?

News, whether positive or negative, travels fast at all institutions. Humans like to be "in the know." Events and milestones viewed as positive are often celebrated, whereas missteps are sometimes discussed transparently and other times not at all. The community might convey a sense of pride in a given area (e.g., "We really excel at recruiting the top ________ in the country/world!"). Alternatively, negative news—among the community and beyond—can pack a wallop and send community trust into a nosedive, making members of the community wonder whether and how it'll move forward.

A culture-sensitive leader needs to have a finger on the pulse of the campus on matters that are most important to the community in general and specifically regarding the level of trust in leaders, units, etc. Keep on top of current happenings as well as past events. Additionally, what and who gets celebrated? Are missteps or negative news dealt with quickly and directly, or are they tiptoed around? Understanding past events, the community's reaction to events, and how positive and negative events are handled will provide a valuable lens for how to best situate your data strategy. It may even uncover supporters and those who may be less than supportive (as well as explain individuals' lack of support).

Scheduling conversations with others, especially people who have been a part of the community for some time, is a good place to start, as are student newspapers, book(s) about your institution, and outside articles. Determine what exactly occurred, what the reaction was inside and outside the community, and how people feel about things now. Understanding the attitudes of members of your institutional community on a variety of topics will provide you with breadth and depth that will inform your data strategy.

Get started with these three practical steps to help others increase their trust in data governance:

- Is there a student newspaper? If yes, how do faculty, staff, and administration feel about the reporting involving data? What issues does the newspaper focus on? Are issues surfaced just once, or are they repeated in such a way that readers are less likely to want to wade into those waters again? Or are the same kinds of data missteps being made repeatedly? Do the data and facts reported indicate a potential data governance opportunity? For example, how is fall enrollment reported and to whom? How does the institution control the messaging, and what happens when those protocols are violated? What does this say about the institution's data culture?

- Determine whether books or newspaper articles have been written about events at (or even the history of) your institution. Review them and compare what's said. How do these themes overlap with your intended data governance outcomes?

- If you're new to an institution, the next time you're at a meeting ask others how long they've been at the institution and where they're located on campus. How do they speak about the institution? About different events or sectors of the institution? What's your assessment of their level of trust in other units/roles/the institution?

7. How is power expressed within your culture?

Power can be expressed in numerous ways within an institution. For some, it may mean access to resources, such as a budget and staff. Others may view power as whose agenda gets promoted over others. Power may also manifest itself in practices that are encouraged and rewarded versus practices that are shunned or shuttered. Knowing how power is leveraged, as part of culture, represents a huge opportunity for data governance professionals.

Identifying those in your institution who hold both formal and informal power over the ecosystem is an important step in ensuring you are communicating and advocating for governance in the most efficient way possible. Aligning yourself, and your work, within a network of colleagues who have had previous successes could serve to accelerate your ability to succeed. Likewise, power also has to be weighed carefully in circumstances where an approach may run counter to a given individual's agenda. In this regard, a data governance leader will need to think carefully and critically about how best to proceed. See our other strategies in this document for building allies, identifying opportunities for institutional success, etc. Understanding how to effectively navigate the culture of power at your institution may be one of the toughest nontechnical challenges for a data governance leader.

Get started with these three practical steps to better define how power is expressed in your culture:

- Look to see whose requests for new staffing, budget increases, or technology enhancements are approved and what areas haven't seen growth. Ask yourself why this is occurring. Look to see if a pattern exists when it comes to who is asking and who is approving. Leverage this information to reshape or reconsider your own approaches. Adopt winning techniques and avoid tactics that may mirror unsuccessful past requests.

- Compare your RACI matrix from a data governance perspective with your personal assessment of who has power within your institution. Are you aligned, or do you need to revisit the roles others should play in your data governance process? Understand the difference between authority stemming from a job title or description versus authority that is rooted in power or influence.

- Differentiate your communication strategy. Culture-first data governance leaders who understand how power is yielded at the institution know they must communicate differently with different audiences. Often a one-size fits all communication approach is doomed from the start. Get specific about whom you are communicating with and how you believe they might react to your content. Use these hunches to revise your approach. You may need to segment your communications based on the audience as opposed to issuing blanket announcements.

8. How does your culture impact who is expected to do the work?

In every social unit (professional or personal) there is "the caretaker"—the person (or persons) everyone goes to when things need to get done, with the expectation that the person will come through. Messages regarding who is expected to perform specific duties or tasks are generally implicitly conveyed, as is who is expected to perform a specific task or type of work (e.g., down-in-the-trenches work versus reviewing the work and signing off). In some instances, caretakers may be expected by others in the group/unit to perform duties or tasks in which the caretakers have no or limited input, that they don't feel well-suited to perform, or for which they don't receive compensation (monetary or otherwise). A culturally aware leader taps into the implicit messages surrounding who does what types of work and how it's perceived by those doing the work so they might modify workflows, workloads, and who is genuinely asked to provide input into the work they are expected to perform and advance.

A good place to start? Speak with your direct reports' reports. What does their daily work consist of? From their perspective, who does (and is expected to do) what type of work? Also, what units or roles continuously come up as being at the forefront of your institutions' initiatives? These people know how things work, who does the work, and whether work expectations align with those who possess formal or informal positions of power. Additionally, they may be the individuals who possess a vast amount of institutional knowledge and were sought out (or were expected) to do the work or know the answer.

Get started with these three practical steps to engage caretakers and the people expected to do the work:

- Throughout your daily conversations, pay attention to what unit/role/person continually pops up as being a go-to resource. Take the time to sit down with them to understand what they do, their skill sets, and their institutional knowledge and determine ways to incorporate their expertise into your data governance efforts.

- Know who is behind the reports you receive. Who generates the reports? Who sets the stage for the reports? What goes into those reports? Be curious to learn more about the process and people involved, and reach out to them. You'll be happy you did. You may even gain an additional data governance supporter!

- Locate your SMEs across the institution and/or within the areas you're interested in learning more. Ask questions about what they do and who else they suggest you speak with to learn even more.

9. How does your culture respond to change?

We all know that velocity is an important attribute of data. The same could be said for your institution's approach to change and adaptation. In many cases sound data governance approaches require us to address practices, systems, and stakeholders who have largely been left to their own devices. Data governance, therefore, can be a positive disruptor to some and a force of negativity for others. How a culture responds to change is an important consideration for data governance leaders in terms of knowing how fast and how hard to push toward goals.

Luckily, we have multiple opportunities to assess our institutions in this regard. Engaging others in conversations about times when a new initiative failed and how the organization responded, and/or times when a new initiative succeeded, teaches us a lot about our community. Learning how to spot signs when change is adopted and why allows us to identify causality that we might leverage for our own work. Taking a few moments to analyze IT or data initiatives that succeeded in the past can help surface elements that worked well. Did a project result in change due to who was driving it? Did it create change due to the effort level involved (or how that effort was described)? Did the project implement change due to the sponsorship or support of a team of executive stakeholders? All these questions represent important signals for those of us working to implement improved data governance.

It is equally important to distinguish between an unwillingness to change purely for the sake of change and an unwillingness to change due to legitimate campus or resource constraints. Understaffing, historic resource challenges, and conflicting technology priorities may all underscore why an organization hasn't adapted data governance approaches faster. A culture-first, analytic leader knows how to separate fear of change from legitimate business reasons and continues to advocate for data governance maturation (even if it is incremental and spread over time).

Get started with these three practical steps to assess your institution's orientation toward change:

- Gather colleagues who are either project managers or staff tasked with leading implementation teams. Inquire about projects that resulted in change versus those that did not. Identify patterns that either help or hurt your chances to effectively implement good governance.

- Look at your accreditation processes for clues. In many cases regional accreditors require institutions to invest in programs that will move the institution forward in a major focus area. How was this task undertaken? Who was engaged to ensure it would succeed? What resources were identified to provide legitimacy? How was the program communicated internally to stakeholders? How did the community respond to the program? Is the program still operating at the institution? Why or why not? Once you understand these factors, ask yourself how your plan for data governance is either in alignment with this approach or differs from it. This should provide you with some insights into what to expect in terms of change.

- If this is not your institution's first attempt at data governance, it is time to employ a tactic from James Collins known as an "autopsy without blame."Footnote7 Identify as many of the former stakeholders involved and dig into why the previous effort may have failed to take hold. Document these challenges with a particular eye toward willingness to change. Asking these stakeholders whether they believe reluctance to change was a major component of the project's failure is also a surefire way to know where you stand in terms of the culture's orientation toward change.

You Are What You Help Create

The elements described above are key to understanding culture as it relates to your efforts to enhance or mature your data governance program. Moving from theory to practice requires a focus on behaviors that help leverage culture more effectively in your work. In addition to the tactics discussed in this article, the following seven behaviors are vital to succeed as a culture-focused data governance leader.

- Values internal and external perceptions

- Identifies unspoken patterns and norms

- Assesses power and influences for good

- Listens for meaning before acting

- Leverages language and storytelling

- Integrates campus beliefs into strategy

- Identifies willing partners and key allies

We know from experience that adopting these behaviors will assist you in navigating the complex waters of your institution's unique culture. Choosing to integrate these behaviors into your next data governance effort should result in seeing, hearing, and thinking differently about your culture and engaging others for success.

Data professionals must engage in more conversations on how to best leverage data governance practices at their respective institutions and focus less on how to actually stand up these efforts. For higher education to move past the implementation phase to the optimization phase will require new approaches that haven't been fully leveraged in the past. Culture can be a powerful tool in your arsenal, if used effectively. It's time to stop discussing structure, tools, and technology as if they exist in a vacuum and start incorporating institutional culture into the data governance and analytics planning process and strategies.

This brings us full circle to another Peter Drucker quote: "The best way to predict the future is to create it." Let's create a stronger future for our institutions by creating a cultural connection to our data governance and analytics efforts.

Notes

- Danette McGilvray, Executing Data Quality Projects: Ten Steps to Quality Data and Trusted Information, 2nd ed. (Cambridge, MA: Academic Press, 2021). Jump back to footnote 1 in the text.

- Robert Birnbaum, How Colleges Work: The Cybernetics of Academic Organization and Leadership (San Francisco: Jossey Bass, 1988). Jump back to footnote 2 in the text.

- Jenay Robert and Betsy Reinitz, 2023 EDUCAUSE Horizon Action Plan: Data Governance (Boulder, CO: EDUCAUSE, 2023); Betsy Tippens Reinitz et al., 2022 EDUCAUSE Horizon Report, Data and Analytics Edition (Boulder, CO: EDUCAUSE, 2022). Jump back to footnote 3 in the text.

- Nicole Lowenbraun, "Good Listening Is More than Simply Paying Attention," blog post, Duarte, August 15, 2022; Matt Abrahams, "It's Not About You: Why Effective Communicators Put Others First," Insights, March 21, 2023. Jump back to footnote 4 in the text.

- Amy Gallo, "What is Psychological Safety?" Harvard Business Review, February 15, 2023. Jump back to footnote 5 in the text.

- Susan Scott, Fierce Conversations: Achieving Success at Work and in Life One Conversation at a Time (New York: New American Library, 2017). Jump back to footnote 6 in the text.

- Jim Collins, Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap…and Others Don't (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2001). Jump back to footnote 7 in the text.

Jason F. Simon is Associate Vice President of Data, Analytics, and Institutional Research at the University of North Texas.

Melissa D. Barnett is the inaugural Data Governance Manager at Georgia State University.

© 2023 Jason F. Simon and Melissa D. Barnett. The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY-ND 4.0 International License.