Today's institutional leaders, working to improve their quality of learning, equitable access, and affordability at scale, can magnify those 3fold gains with four uses of technology.

Over the past few years, I've studied six higher education institutions that have been improving their quality of learning, equitable access, and affordability. No single innovation drove those 3fold gains. Instead, each institution has developed constellations of mutually supportive initiatives. For each institution, this development took many years. And each has applied technology in at least four ways to make their innovations even more effective.

The Urgency of 3fold Gains

The urgency of these three needs has been amply documented.Footnote1

- Quality of Learning. At least a half-dozen lines of inquiry have drawn the same conclusion: on a national (U.S.) scale, a large majority of students completing college fall short in many capabilities that faculty and employers agree are essential for graduates—capabilities such as critical thinking, the ability to work with people from different cultures, and communication.Footnote2

- Equitable Access. Certain categories of students have been given the short end of the stick for their entire lives, making them less likely to succeed in higher education as it's traditionally organized. As a result, far too many in the nation's talent pool never make it to college or, if they do, drop out. That situation is not helped by a system that invests the least in educating those students most in need of effective, inclusive teaching.

- Affordability: The cost of a college education in real dollars continues to explode. The possibility of long-term debt scares off some potential students while hampering the most indebted from investing their post-college income in their futures. Meanwhile, higher education faces stiffer competition for money—for example, from state and federal budgets. "Free college" is not, by itself, a solution; the costs of higher education also need to be low enough that the public and its representatives are willing to pay for them.

To make 3fold gains, colleges and universities need to make certain changes in the character of teaching and learning. Certain forms of peer interaction and other active learning can improve the quality of learning for almost all students, and the most value accrues to students from underserved groups, resulting in more equitable access as well.Footnote3 These gains can also improve affordability, a function both of available resources and of the motivation to spend them. (For example, you might decide you can't afford a $100 jacket while simultaneously buying a used car for $10,000.) Gains in retention and graduation rates increase the value of higher education for the next rounds of incoming students. Speed to graduation can reduce the time and money that students invest. For institutions, the cost of providing education per graduating student (i.e., all instructional costs divided by the number of graduating students) drops as well, because the cost per graduate includes the costs to educate those students who didn't make it to graduation. Additionally, institutional revenue increases when more students stay until they graduate, paying tuition for those additional semesters.

The six institutions I studied—Georgia State University, Governors State University, Guttman Community College, Southern New Hampshire University's College for America, the University of Central Florida, and the University of Central Oklahoma—demonstrate that large-scale improvements in teaching and learning require complementary changes in institutional practices, policies, culture, and relationships. Some of the technology uses highlighted below aid teaching and learning, while others make those organizational changes more potent.

Georgia State University: Putting It All Together

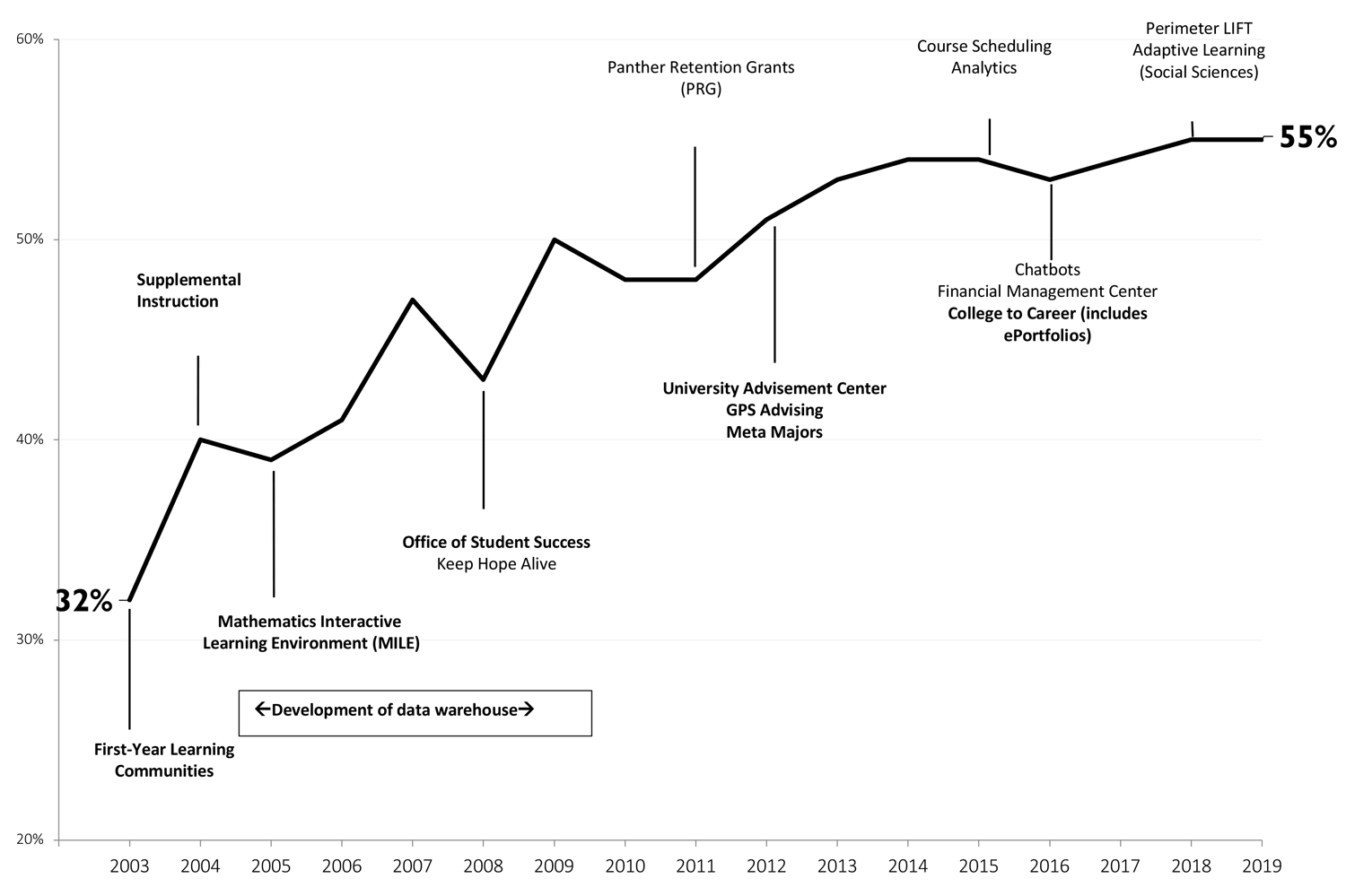

The recent history of Georgia State University (GSU) illustrates all these principles in action. GSU, in Atlanta, has been making 3fold gains since at least 2003. Back then, the institution was a growing public, research-intensive, regional university with over 20,000 undergraduates and several thousand graduate students. Unfortunately, only about one in three entering students graduated from GSU within six years. Graduation rates were still lower for students who were low-income, first-generation, or African American. Graduation rates were only 29 percent for African American students and a mere 18 percent for African American males. Pell Grant students were graduating at rates far below those of non-Pell students. In fact, in 2003, only half of first-year African American Pell students made it to their second year.Footnote4

That's when GSU scaled up its use of first-year learning communities, which are still in place today. Such continuity is true of almost all the relevant reforms at GSU: they were intended from the start to be sustainable and affordable at scale. And as we'll see, some of those initiatives would have been inconceivable without technology.

Fast-forward sixteen years. By 2019, the four-year enrollment had grown by more than 20 percentage points. The fraction of entering students from underserved groups had grown as well. Surprisingly, graduation rates had improved dramatically during that period. This was no coincidence. Year after year, GSU added more sustainable practices and services, many of which were improvements in pedagogy and academic support and all of which were aimed at improving quality of learning and equitable access. The growing constellation of aligned innovations helped improve graduation rates for all students, one sign of improved quality of learning. Over that same time, African American and Latino/Latina six-year graduation rates grew to match or exceed six-year graduation rates for White students, a gain in equity. These same innovations directly influenced affordability too. When students graduate earlier, for example, they earn a degree at lower expense in both money and time. And GSU estimates that each percentage point increase in six-year graduation rates produces $3 million extra in tuition revenue.

Figure 1 shows just a few of the GSU initiatives, plotted against graduation rates. This figure offers the best single illustration of the process of pursuing 3fold gains: as the institution gradually assembles a sustainable constellation of educational strategies and organizational changes, graduation rates continually improve. The vertical axis of figure 1 represents the increasing six-year graduation rate for students who entered GSU and stayed to earn their bachelor's degrees. Today it's possible to calculate six-year graduation rates that include students who entered GSU and graduated within six years from either Georgia State or other institutions. Both categories of graduation rates have been about the same—White students or Black students, Pell-eligible or not—for the last several years.

Several of the initiatives in figure 1 were possible only because of technology. For example, the redesigned math courses depend on a mix of learning supports, including adaptive courseware and human coaching, in their Mathematics Interactive Learning Environment (MILE) classrooms. Data warehousing—validating and integrating information from many sources—improves the process of identifying unnecessary barriers to student success and estimating the success of initiatives intended to lower those barriers. GPS Advising allowed more effective advising partly by using big data to keep students, faculty, and advisors promptly informed and partly by adding more academic advisors (the increase in tuition revenue mentioned above paid for those new positions).Footnote5

The GSU constellation comprises three types of initiatives:

- Some initiatives changed teaching and learning at scale (e.g., first-year learning communities and redesigned introductory math courses). These are changes in educational strategy.

- A second set of initiatives changed internal organizational practices and culture (e.g., data warehousing and a newly created Office of Student Success to coordinate and expand the constellation), helping to scale up and sustain those emerging educational strategies. These are changes in organizational foundations.

- A third group of initiatives changed GSU's interactions with its wider world (e.g., the expanding use of e-portfolios to help employers and graduate schools assess students' capabilities). These are changes in how the institution interacts with its wider world—that is, its operating environment.

By aligning initiatives within and across all three domains, GSU was better able to scale up and sustain its pursuit of 3fold gains.

A Framework for 3fold Gains

Despite many differences across the six institutions I studied, there are also some resemblances in their assumptions and practices. To provide some of the thrust for improved learning pathways, these institutions all rely on High-Impact Practices (HIPs) such as learning communities, undergraduate research, service learning, internships, capstone courses, and e-portfolios.Footnote6 George Kuh, Ken O'Donnell, and Carol Geary Schneider summarized research demonstrating that a sequence of HIPs improves learning for all students and even more for students from underserved groups.Footnote7 Among the benefits of HIP educational strategies are improved retention, graduation rates, and speed to graduation, all of which help make education more affordable for students. In other words, at scale, HIPs can contribute to an institution's quality of learning, its equity of access, and its affordability. Of course, attributing all of the improvements to HIPs is an over-simplification; however, for this article, we'll focus on HIPs. (Spoiler alert: One of the most important uses of technology is to make HIPs even more varied and powerful.)

Educational reforms such as HIPs are difficult to sustain on a large scale unless complementary changes are made in the institution's educational strategies, organizational foundations, and how it interacts with its wider world. For example, sustaining HIPs at scale is easier if the institution's constellation also includes the following:

- Courses of study organized around one or two HIPs each year (educational strategy)

- An assessment program that gathers, analyzes, and shares data about how students' capabilities develop from year to year (organizational foundations)

- A learning-centered culture that is reflected and reinforced by formal and informal reward systems for faculty and staff (organizational foundations)

- An office that supports a network of off-campus sites at which all students can work on undergraduate research, capstone projects, and other HIP-relevant work (wider world interaction)

- Admissions strategies that use attractive HIPs to help market academic programs to potential students (wider world interaction)

- Alumni donor campaigns that raise money to support undergraduate research and other HIPs (wider world interaction)

What's most important about such constellations of elements is how the impact of each initiative is influenced by many other elements in that constellation. To put this another way, 3fold gains are fostered by an institution's constellation of initiatives. As the GSU example suggests, constellations are usually assembled one or two initiatives at a time. Each new initiative should be chosen in part because the institution could afford to sustain it at scale. Without that assurance, there would just be churn, with innovations continually appearing and disappearing.

Four Ways to Use Technology for 3fold Gains

Now that we've got a sense of the general framework, where can focused applications of technology make substantial contributions to an institution's constellation for making 3fold gains? Instead of trying to catalogue all such innovations, I will focus on just four.

1. Technologies to scale up HIPs (educational strategy)

Some of the most influential HIPs are driven by meaningful, motivating projects tackled by students individually or in teams. Over the last half-century, technology opened more potential projects that are both feasible and meaningful for students, even first-year students. Examples of such technologies include spreadsheets, statistical software, geographic information systems, tools for creating and performing digital music, and tools for creating websites. Study-abroad experiences (a HIP) can become even more powerful when students connect with their research sites long before they arrive and long after they leave. Similarly, service learning projects and internships no longer have to rely on face-to-face contact, phone calls, and mail. Ironically, as powerful and widespread as this use of technology is, it's virtually invisible for anyone not directly participating in that course. Ironically, using technology to multiply the power of HIPs is the single most important contribution to 3fold gains. And one of the most important challenges for IT organizations going forward is to work with others to train students in the substantive use of such tools (e.g., how to conduct more effective conversations in threaded discussions and how to increase the impact of web-based projects on end-users.)

2. Programmatic e-portfolios to deepen and document the development of students' capabilities (educational strategy)

A programmatic e-portfolio is used by students to reflect on lessons from their work. For example, the University of Central Oklahoma (UCO) is committed to transforming how students see, think, and act in the world. To help accomplish this, UCO has systematized its support for developing five student capabilities, or "tenets": global and cultural competencies; health and wellness; leadership; research, creative, and scholarly activities; and service learning and civic engagement.

To accelerate and document student transformation in these five tenets, UCO developed the Student Transformative Learning Record (STLR). Students have the option of posting artifacts and reflections that illustrate their development in any or all of these five tenets. Artifacts can come from courses, from co-curricular activities such as summer research projects, and from extracurricular activities such as leadership developed through athletic work.

In the context of UCO's constellation, the STLR helps leverage institutional transformation. For example, faculty are encouraged and helped to develop dual-purpose assignments. The assignments are graded in the traditional way, but students may also submit their assignment—with a reflection on lessons learned—to their STLR account to help document how they're progressing toward personal transformation within one of those five tenets. In a happy surprise, many faculty members' assumptions were challenged by students' reflections about how those class projects were influencing their personal development. That impact went far beyond content delivery. The STLR framework and records also transformed the university's interactions with its wider world as the STLR helped many students, parents, and employers better understand the goals of a UCO education.

3. Decision support systems to help administrators, faculty, and students understand and lower barriers to students' academic success (wider world interaction)

Programmatic e-portfolios such as the STLR are just one example of how appropriate uses of technology can help administrators, faculty, and students see what they're accomplishing. Previously, their view of learning was limited largely to what could be seen and heard inside the course and its classroom.

As mentioned above in the discussion of GSU, early in the development of its constellation, the university began validating reports and organizing information from many sources across campus. One purpose was to enable administrators, faculty, and staff to answer important questions about the nature and causes of failure by students. For example, the data warehouse helped them see the number of entering students who started a pre-nursing program and how many of them completed that program but were then not admitted to the undergraduate nursing program. What did those stymied students do next? Are the students' trajectories similar for non-Pell and Pell-eligible students? Using these kinds of evidence, nursing faculty, staff, and administrators reconceived the pre-nursing and nursing programs. Another form of decision support, also mentioned above, is the combination of the GPS platform with the addition of more academic advisors.

4. Online and blended learning to take the framework to a new level (educational strategy, organizational foundations, and wider world interaction)

The University of Central Florida (UCF) has used online learning to strengthen its means of achieving 3fold gains by providing an education at least as good as, slightly more equitable than, and also more affordable than what was possible with only physical learning spaces. In 2021, almost exactly half of all credits at UCF were earned in online and blended courses.

Let's take a quick look at UCF's quality strategy. The relevant policies were born in the late 1990s, almost immediately after the university offered its first online course. Back then, academic deans resolved that before their colleges offered any online courses, their faculty should get substantial education and assistance in designing online courses. Today, UCF invests around $20,000 in staff assistance and faculty stipends for each faculty member to learn how to develop an online course. There's a waiting list, not least because participation in this 80-hour workshop is required before faculty can teach online. Those funds, and more, come from distance learning fees. Students in fully online programs still pay less than campus students, however, because several other campus-specific fees are waived. For a quarter-century, UCF has been preparing up to 200 faculty each year to teach online. Almost all of them also teach on campus, so online courses drive improvement in campus courses taught by those same faculty.

Meanwhile, the online and blended programs aid affordability in two additional ways. Most obviously, demand for online courses has helped UCF expand far more quickly than a requirement for new classroom buildings would have allowed. Second, the greater the number of online courses students take, the faster they graduate. According to UCF: "Undergraduate students who take roughly 40 percent of their courses online graduate in less than 4 years, compared with 4.3 years for those in only face-to-face courses."Footnote8 Once again, faster time to graduation saves students time and money while reducing the costs of teaching them. It's worth repeating that all of this happens in the context of a constellation of institutional practices, policies, culture, and relationships. Simply offering more online courses is no guarantee of anything. But in the right context, substantial online offerings can make strategies for 3fold gains even more effective, accessible, and affordable.

In a Nutshell

Colleges and universities can improve their quality of learning, equity of access, and affordability. HIPs such as undergraduate research, service learning, and capstone courses inspire greater effort and foster more learning by students. Students from previously underserved groups benefit even more than other students from such practices. Affordability improves for students when they're less likely to drop out, more likely to graduate, and more likely to graduate earlier; those changes save students time and money, including money provided by taxpayers and donors. Meanwhile, as retention and graduation rates increase, institutional revenues expand too, paid by the students who are no longer dropping out.

Technology can supercharge this general framework for 3fold gains by enriching the variety of HIPs, which then widens and deepens the kinds of motivating projects that students can tackle. E-portfolios, for example, can provide a scaffold for deeper learning and broader understanding of the goals and outcomes of higher education. In addition, integrated databases can help administrators, advisors, faculty, and students get a better sense of what accelerates student success and what currently impedes it. Finally, institutions that develop large, integrated programs of online and blended learning to support this framework have the potential for even greater gains.

The examples I've provided from Georgia State University, the University of Central Oklahoma, and the University of Central Florida show that it is indeed possible for a college or university to visibly improve its quality of learning, equitable access, and affordability. Their experiences hint at the 3fold gains that other institutions could achieve over the next five to ten years.

Notes

- A detailed summary of the evidence of these three needs can be found in chapter 1 (freely available) of Stephen C. Ehrmann, Pursuing Quality, Access, and Affordability: A Field Guide to Improving Higher Education (Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing, 2021). Jump back to footnote 1 in the text.

- Association of American Colleges & Universities, On Solid Ground: VALUE Report 2017. Jump back to footnote 2 in the text.

- George Kuh, Ken O'Donnell, and Carol Geary Schneider, "HIPs at 10," Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 49, no. 5 (2017). Jump back to footnote 3 in the text.

- "Georgia State University Campus Plan Update 2021," Complete College Georgia (website), accessed April 6, 2022. Jump back to footnote 4 in the text.

- For a quick introduction to why and how GSU uses GPS, see "The Story Behind GPS Advising." Cautionary note: Watching only this video, you may assume that all these gains were created by GPS alone. But figure 1 illustrates how GPS is just one element of GSU's expanding constellation of initiatives. Jump back to footnote 5 in the text.

- Ehrmann, Pursuing Quality, Access, and Affordability, 133–135; George D. Kuh, High-Impact Educational Practices: What They Are, Who Has Access to Them, and Why They Matter, American Association of Colleges & Universities, 2008. Jump back to footnote 6 in the text.

- George Kuh, Ken O'Donnell, and Carol Geary Schneider, "HIPs at Ten," Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning 49, no. 5 (November 2017). Jump back to footnote 7 in the text.

- "Distance Learning," University of Central Florida (website), accessed March 28, 2022. Jump back to footnote 8 in the text.

Stephen C. Ehrmann, a researcher in distance education, previously served in technology and administrative roles at George Washington University, the University System of Maryland, the TLT Group, the Annenberg/CPB Project, the Fund for the Improvement of Postsecondary Education (FIPSE), and Evergreen State College.

© 2022 Stephen C. Ehrmann. The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0 International License.