The pandemic has provided educators with unprecedented opportunities to explore blended learning and identify the practices and approaches that provide real and lasting value for students.

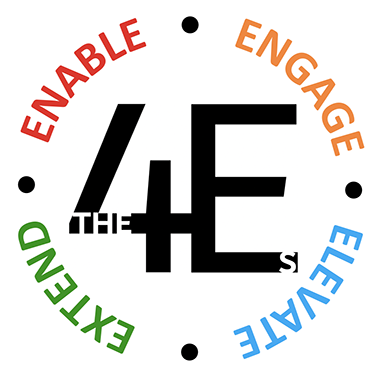

Students and instructors have returned to classrooms on campuses across the country, with a strong desire to rediscover some normalcy following more than a year filled with Zoom meetings and learning apart. At the same time, instructors and students have changed during the pandemic and are coming back to the classroom with new skills and different perspectives. As a result, rather than resuming business as usual, instructors should take inventory of what went well during emergency remote teaching, as well as what they missed most about in-person teaching when they were apart from their students, and begin to blend the two to design the new normal. To help instructors through this process, we have developed a framework to draw their attention to important advantages of blended learning that they should consider as they evaluate what is possible moving forward. Specifically, we have built on previous research and frameworks—such as David Merrill's e3 approach and Liz Kolb's Triple E FrameworkFootnote1—to develop the 4Es framework (see figure 1) that asks instructors whether their blended learning strategies:

- ENABLE new types of learning activities;

- ENGAGE students in meaningful interactions with others and the course content;

- ELEVATE the learning activities by including real-world skills that benefit students beyond the classroom; and

- EXTEND the time, place, and ways that students can master learning objectives.

Do Your Blended Learning Strategies ENABLE New Types of Learning Activities?

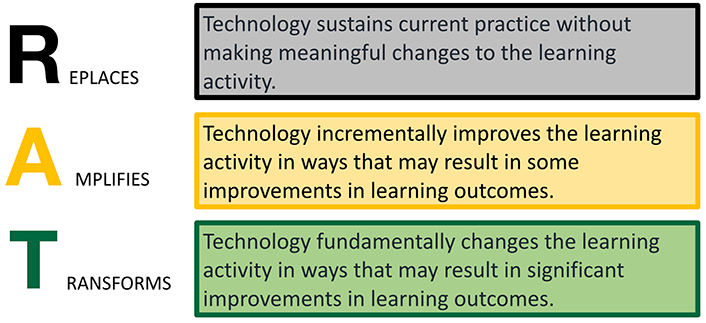

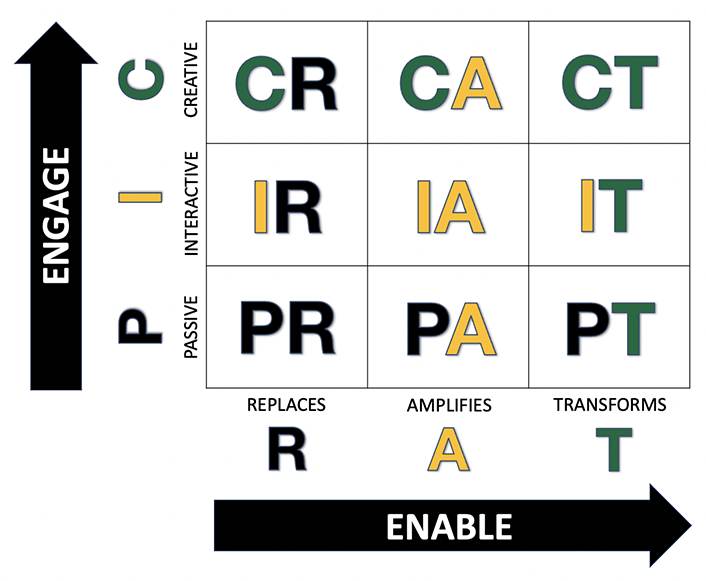

Royce Kimmons, Charles Graham, and Richard West used the RAT framework to explain that blended learning strategies can use technology in ways that replace, amplify, or transform learning activities (see figure 2).Footnote2

Instructors have a long history of using technology to simply replace or digitize learning activities that were previously done without technology. For example:

- In-person lectures are replaced with Zoom lectures.

- Writing an essay by hand is replaced by typing an essay.

- Writing on a chalkboard is replaced by writing on a digital whiteboard.

- Chalk on a board is replaced by pixels on a screen.

- Reading a textbook is replaced by reading an e-book.

These replacements can be a fine use of technology. Digitizing learning activities can reduce costs and improve access. Additionally, replacing a learning activity by using technology can make some learning activities more efficient than they would be without technology. For instance, an essay typed in a word processor can be revised more easily and quickly than a handwritten essay. However, simply replacing an activity will not improve learning outcomes. In a best-case scenario, students will achieve the same learning outcomes, only more quickly and/or cheaply.

To enable new types of learning that improve learning outcomes, instructors need to use blended learning strategies that move beyond replacing in-person activities with online activities to using strategies that amplify or transform learning activities from what could be accomplished without technology.

Amplifying a learning activity requires instructors to introduce technology in ways that enable incremental improvements, even as the core of the activity remains largely unchanged. For instance, when they read students' essays, instructors may find that many of their students have met the target learning outcomes. As a result, the instructors may choose to amplify the essay-writing process by having students work in a shared document that enables better collaborative opportunities, peer reviews, instructor feedback, and editing. Students can also include multimedia elements to enhance what is written in the essay. Or instructors might use technology to allow students to publish and share their essays in authentic ways. Instructors might also use technology to improve pre-writing activities by engaging students in an online discussion activity to brainstorm and formulate ideas for their essays. What's important to recognize is that although the core activity—writing an essay—remains the same, technology enables incremental improvements, some of which could impact learning outcomes.

Transforming a learning activity is different from amplifying because the goal isn't to improve the activity but to use blended learning strategies in ways that introduce a new learning activity that wouldn't be possible without technology. For instance, rather than making improvements to the essay, instructors could choose to transform the learning activity by tasking students with writing a script, editing a video, and "premiering" their videos to those in the course and others who are invited to participate.

Do Your Blended Learning Strategies ENGAGE Students in Meaningful Interactions with Others and the Course Content?

"Engagement" is a term that is used frequently to mean a lot of different things. A 2020 review of research identified three dimensions of engagement:Footnote3

- Behavioral: the physical behaviors required to complete the learning activity

- Emotional: the positive emotional energy associated with the learning activity

- Cognitive: the mental energy that a student exerts toward the completion of the learning activity

Instructors often refer to these three dimensions of engagement when they talk about engaging students' hands, hearts, and heads (see figure 3).

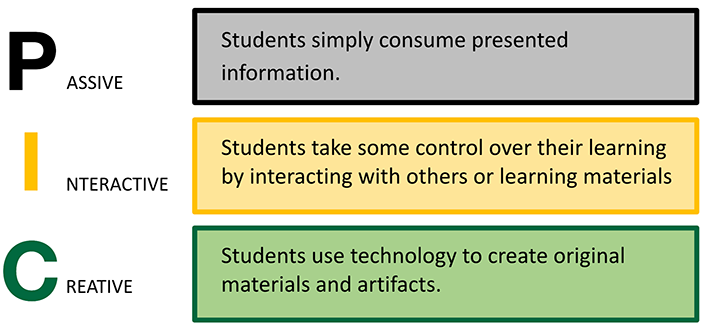

Of the three dimensions of engagement, behavioral engagement is the easiest to observe and categorize. Specifically, Kimmons, Graham, and West used the PIC framework to identify three types of behavioral engagement: passive, interactive, and creative (see figure 4).Footnote4

Passive learning examples include students watching a video, listening to a podcast, and attending a lecture. In some ways, these passive learning tasks represent a lack of engagement because they don't require or even allow students to make meaningful contributions to the learning activity.

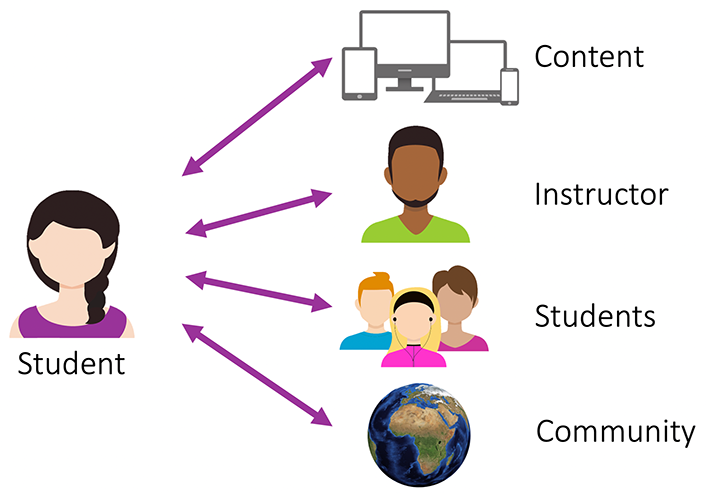

Interactive activities are dynamic and require students to actively participate. Interactive activities include tasks in which students interact with online content and tools. Interactive activities can also include opportunities for students to communicate with others such as the instructor, other students, and those outside the classroom (see figure 5).

Creative activities go beyond participation to actually creating something original such as a blog post, edited video, or website. Table 1 identifies some additional examples of online passive, interactive, and creative activities.

Table 1. Examples of Passive, Interactive, and Creative Activities

| Passive | Interactive | Creative |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

It's important to note that each type of behavioral engagement is important at different stages of the learning process. For instance, students may passively listen to a short lecture or watch a video before interacting with their peers regarding their thoughts about what they learned during the passive activity. Similarly, if students are tasked with creating a video essay, they will likely start with passive activities to develop a background understanding of the topic or to learn how to use the video-editing program. Students could then interact with their peers to collaboratively create the video. Instructors can also consider when and where passive learning activities occur. For example, sometimes a flipped classroom requires having a passive video-watching experience online to make time and space for an interactive/creative learning experience in person.

An important part of evaluating your blended teaching is to see the value of passive learning activities while also understanding that these types of activities are limited in terms of deepening students' learning. Passive activities such as watching a video or reading an article alone do not require students to demonstrate their comprehension of content or encourage higher levels of cognitive engagement, such as applying, evaluating, or creating. Because too much time spent in passive learning activities will limit students' engagement, instructors should be sure to leave ample time for interactive and creative activities.

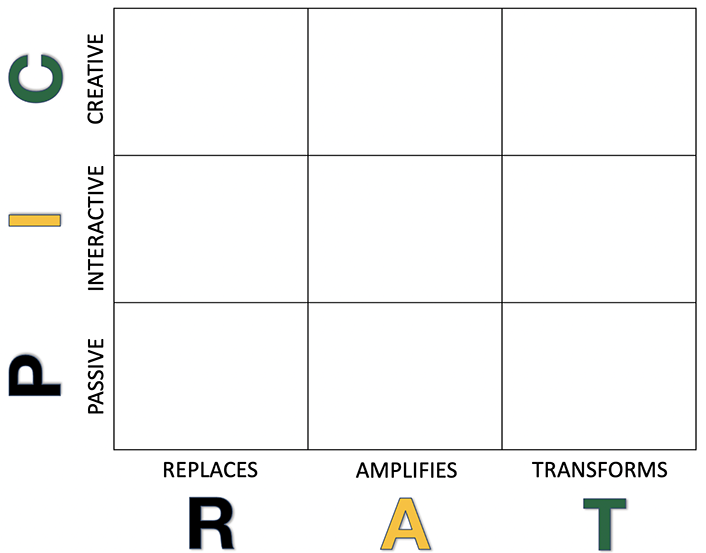

Kimmons, Graham, and West combined the PIC and RAT frameworks to form the PICRAT framework and matrix, which allow instructors to chart how technology is being used in their blended learning strategies.Footnote5 Figure 6 is an adaptation of Kimmons, Graham, and West's original matrix. The matrix is a helpful tool for instructors to consider what the technology adds to the activity and how students are interacting with that technology. Ask yourself the following questions:

- Is the technology being used to increase student engagement by making learning activities more interactive and/or creative?

- Is the technology being used simply to replace activities or to amplify and transform them?

When planning new blended or online activities, we recommend starting by focusing on the learning objective(s) and then pulling out a piece of paper or pulling up a word processing document and filling out the PICRAT matrix (see figure 7) with various ways that technology could be used to teach the learning objective(s).

Moving up and across the matrix will likely improve the learning activity by leveraging technology to make the experience more interactive or engaging and introducing new ways of learning, but note that the PICRAT matrix doesn't actually measure the quality of the learning activity. Instructors could transform a learning activity by having students create something that wouldn't be possible without technology, but that change might not actually improve students' learning or experience. In fact, students' learning can be transformed for the worse. For instance, using the example shared above, an instructor could transform an essay writing activity so that students create an edited video instead. Although this change may be positive for many students, some students might detest making an edited video and refuse to participate. Similarly, an instructor might transform a passive learning activity into a creative learning activity that isn't as aligned to the learning outcomes. As a result, when amplifying or transforming a learning activity to increase students' behavioral engagement, consider the other two dimensions of engagement—emotional engagement and cognitive engagement. Students will perceive the activity as "busy work" if instructors only engage their hands but fail to also engage their hearts and minds (see figure 8).

Do Your Blended Learning Strategies ELEVATE the Learning Activities to Include Real-World Skills That Benefit Students Beyond the Classroom?

In addition to creating learning activities aligned with the course learning objectives, blended learning strategies can elevate students' learning to also include real-world skills that benefit students beyond the classroom. For example, the Partnership for 21st Century Learning stresses the need for students to develop the 4Cs—communication, collaboration, critical thinking, and creativity skills.Footnote6 While widely referenced and important, the 4Cs model takes a somewhat narrow view of the skills that students need to succeed beyond the classroom. For Ontario's education agenda, Michael Fullan expanded on the 4Cs to include character education and citizenship.Footnote7 Social-emotional learning is also critical for human development. These skills are best developed in a social learning environment. Of course, students are unable to develop communication, collaboration, and citizenship skills in isolation. Even critical thinking and creativity skills are best developed when working with others. This reality provides more support for balancing passive activities with interactive and creative activities while urging instructors to elevate their instruction.

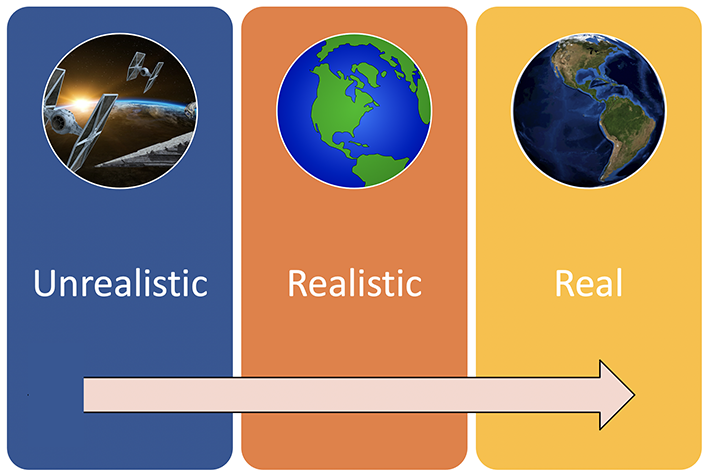

Learning activities are also best elevated when they are situated in authentic tasks and projects. Three levels of authenticity should be considered when choosing the problems students will be working on and the stakeholders that students will be working with (see figure 9):

- Unrealistic: These scenarios and problems can be out of this world—literally! Stakeholders and problems can be science fiction and include anything from time traveling to establishing a colony on Mars. They are intended to make the unit more exciting and emotionally engaging while still requiring students to demonstrate important knowledge and real-world skills.

- Realistic: These are scenarios and problems that feel like they are real but aren't. Real people can even serve as stakeholders, but they are just acting. For example, students might simulate creating a new business by coming up with a new product and working in groups to come up with the name of the product, a business plan, and a marketing plan. It is completely realistic, but they won't be really starting a new business.

- Real: This is the gold standard because you have real people who are genuinely interested in students' work and will benefit from it. These stakeholders can be of any age and in or out of the institution. For example, pre-service instructors in a course on teaching with technology may collaborate to develop a workshop on blended teaching for a local school district. Art students could also curate an actual art gallery showcasing works from local artists.

Authentic assessments are often renewable rather than disposable. As David Wiley explained, "A 'renewable assessment' differs in that the student's work won't be discarded at the end of the process, but will instead add value to the world in some way."Footnote8 Consider the target audience of most assessments—for whom are students completing assessments? Themselves? Their community? The instructor? Often assessments are completed for an audience of one, the instructor. The instructor then evaluates the assessment, provides the student with some feedback, returns the assessment to the student, and hopes that the feedback enriches the student's learning before the assessment is thrown in the physical or digital trash can. David Wiley referred to these assessments as disposable assessments. They are meant to be used and then discarded without retaining any real-world value.

A movement toward assessments that can exist in a world larger than the four walls of a singular classroom can make learning more authentic and elevate what students learn and do beyond the content-based curriculum and contexts. For example, a community college instructor who worked with one of the authors found that having her students write an openly licensed textbook that would be shared with other students instead of traditional essays prompted them to submit higher quality work than they previously had. Students want to know that their work matters and is destined for more than the nearest trash can (see table 2 and the sidebar "Additional Resources about Assessments").

Table 2. Examples of Renewable and Disposable Assessments

Renewable Assessments

|

Disposable Assessments

|

|---|---|

|

|

Additional Resources about Assessments

-

Christina Hendricks, "Renewable Assignments: Student Work Adding Value to the World," Flexible Learning, University of British Columbia, October 29, 2015.

-

Christina Hendricks, "Non-Disposable Assignments in Intro to Philosophy," You're the Teacher, University of British Columbia, August 18, 2015.

-

"From Consumer to Creator: Students as Producers of Content," Flexible Learning, University of British Columbia, February 18, 2015.

-

David Wiley, "What Is Open Pedagogy," Improving Learning, October 21, 2013.

Do Your Blended Learning Strategies EXTEND the Time, Place, and Ways That Students Can Master Learning Objectives?

Another way that blended learning strategies can improve learning activities is by extending the time, location, and ways that students can complete them. Attempting to extend students' learning time and location is nothing new. For instance, students have long had flexibility in the time and location that they completed assignments. However, too often students are tasked with completing assignments outside class without adequate support, resulting in frustration and stress.

Using technology, instructors can not only provide students with more sensory-rich learning materials, but, within a learning management system (LMS), they can also provide digital scaffolding and direction to successfully complete learning activities using those materials. For instance, it is relatively easy for instructors to create short instructional videos that can help students learn new concepts or complete learning tasks. Kareem Farah explained that creating instructional videos allowed him to "clone" himself so students could receive his help the moment they needed it, not when he was presently available to help them.Footnote9 Once instructors feel comfortable making quick videos, they can use them to provide targeted support anytime students find something confusing or difficult. This allows instructors to tailor lessons to specific students or course sections.

Instructors can also extend the ways in which students complete learning activities. For instance, instructors might provide multiple learning paths for students to choose from. Creating multiple activities that all lead toward mastery of learning objectives allows students choice in the learning path—hopefully with choices that will motivate them and inspire them to do their best work. Once learning has been extended, instructors can also provide students with opportunities to form their own learning path and/or set their own learning goals. The taxonomy of learner agency presents a scaffold for moving students from a "one size fits all" learning approach to an instructional approach that provides learners with guided choices for their own learning.Footnote10 These choices could include setting performance or learning behavior goals related to learning objectives, choosing how to demonstrate learning and understanding, or choosing specific resources to use or topics to study within a given learning objective. At the highest levels of extending learner autonomy, learners may even create their own learning outcomes, assessments, and activities related to the goals of a course.

Conclusion

Combining in-person and online instruction doesn't mean that the blended learning will be high quality—or even good. As you begin to blend your students' learning, you will likely find that some lessons or even entire instructional units don't work as well as expected. The opposite will also be true, however, and you will find that some blended lessons and modules go incredibly well. It's important to carefully evaluate what works and what needs to be improved or even replaced. A J-curve should be expected anytime instructors try something new.Footnote11 The 4Es framework can help you recognize quality blended teaching and learning. Specifically, as you plan new blended instructional units or evaluate previous blended instruction, ask if your instructional unit would or did:

- ENABLE new types of learning activities?

- ENGAGE students in meaningful interactions with others and the course content?

- ELEVATE the learning activities by including real-world skills that benefit students beyond the classroom?

- EXTEND the time, place, and ways that students can master learning objectives?

Notes

- M. David Merrill, "Finding e³ (effective, efficient, and engaging) Instruction," Educational Technology 49, no. 3 (May–June 2009): 15–26; Liz Kolb, Triple E Framework. Jump back to footnote 1 in the text.

- Royce Kimmons, Charles R. Graham, and Richard E. West, "The PICRAT Model for Technology Integration in Teacher Preparation," Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education 20, no. 1 (2020). Jump back to footnote 2 in the text.

- Jered Borup, Charles R. Graham, Richard E. West, Leanna Archambault, and Kristian J. Spring, "Academic Communities of Engagement: An Expansive Lens for Examining Support Structures in Blended and Online Learning," Educational Technology Research and Development 68 (February 14, 2020): 807–32. Jump back to footnote 3 in the text.

- Kimmons, Graham, and West, "The PICRAT Model." Jump back to footnote 4 in the text.

- Ibid. Jump back to footnote 5 in the text.

- See "P21 Framework Definitions." Jump back to footnote 6 in the text.

- Michael Fullan, Great to Excellent: Launching the Next Stage of Ontario's Education Agenda, Ontario Ministry of Education, 2013. Jump back to footnote 7 in the text.

- David Wiley, "Toward Renewable Assessments," Improving Learning, July 7, 2016. Jump back to footnote 8 in the text.

- Kareem Farah, "Blended Learning Built on Teacher Expertise," Edutopia, May 9, 2019. Jump back to footnote 9 in the text.

- Charles R. Graham, Jered Borup, Michelle A. Jensen, Karen T. Arnesen, and Cecil R. Short, "K–12 Blended Teaching Competencies," (Provo, UT: EdTechBooks.org, 2021). Jump back to footnote 10 in the text.

- Charles R. Graham, Jered Borup, Cecil R. Short, and Leanna Archambault, K–12 Blended Teaching: A Guide to Personalized Learning and Online Integration (Provo, UT: EdTechBooks.org, 2019). See, specifically, section 6.5 of "Blended Design in Practice." Jump back to footnote 11 in the text.

Jered Borup is an Associate Professor in the Division of Learning Technologies at George Mason University.

Charles R. Graham is a Professor in the Department of Instructional Psychology and Technology at Brigham Young University.

Cecil Short is an Assistant Professor of Practice of Blended and Personalized Learning in the Department of Curriculum and Instruction at Texas Tech University.

Joan Kang Shin is an Associate Professor in the Division of Advanced Professional Teacher Development and International Education at George Mason University.

© 2022 Jered Borup, Charles R. Graham, Cecil Short, and Joan Kang Shin. The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0 International License.