In 2018, Colorado Technical University (CTU) introduced CTU Messenger, a text messaging tool that allows students to communicate with their advisors, faculty, and support staff. The tool has provided CTU with unique insights into students' classroom experiences.

Many of the students attending Colorado Technical University (CTU) are working adults with social and family responsibilities and limited time. Providing targeted assistance and outreach for these students is crucial to their success; however, getting feedback from those who are the most in need is challenging. Historically, CTU received feedback from students through many channels, including emails, phone calls, surveys, and other types of communication that are not always aligned with how students prefer to communicate or are not always reflective of those who are the most likely to be in distress.

In 2018, the university introduced CTU Messenger, a text messaging feature that allows students to communicate with their advisors, faculty, and support staff. CTU Messenger has increased students' communication with faculty and staff. However, the most noteworthy change has been the shift in content that students communicate to faculty. The informal nature of a text-style communication tool has impacted not only how CTU students communicate but also what they communicate. With the introduction of the two-way CTU Messenger tool, the university can collect feedback from more than 80 percent of its population in real time. More than 240,000 conversations were reported in 2020 alone.

CTU Messenger is primarily used through the university's student and faculty mobile applications, but it is also available through the learning management system (LMS). Sending messages through CTU Messenger is similar to texting. The service allows faculty and student advisors to communicate with students in real time and share comments, images, and attachments. Notably, students share details about their personal, technology, and course-content challenges more frequently through CTU Messenger than they do with other methods of communication. Insights from these conversations help CTU faculty and student advisors identify students who would benefit from early targeted interventions.

To analyze CTU Messenger comments more efficiently and effectively, the marketing team at CTU utilizes Kapiche, a text-analysis reporting tool that employs machine learning and natural language processing algorithms, including Google Sentiment Analysis, to discern sentiments, trends, and themes in student comments. The academic, marketing, and student advising staff at CTU actively coordinate communication based on themes identified through Kapiche, including separating messages for outreach, and implement solutions at both the student and institutional levels. In CTU's enrollment agreement, students acknowledge that the information they share internally will be reviewed (as noted in the CTU Privacy policy) for themes as well as specific notations. For example, if a student explicitly mentions COVID-19 and includes the key words "hospital" and "illness," these messages are provided to faculty and student advising teams so that they can reach out to these students. Messages that mention "economic hardship" and "job challenges" also indicate student distress and are identified for additional student outreach. In most cases, outreach happens within twenty-four hours, but in some cases, it occurs almost immediately.

Embracing Text Messaging as a Communication Tool

Smartphones and mobile devices are staples for college and university students. A survey conducted by the University of the West Indies found that 67 percent of respondents never turn off their mobile phones, always have the device with them, and check for text messages a minimum of one hundred times a day.Footnote1 Some colleges and universities have utilized text messaging to send one-way communications to students. St. Mary's University found that potential students who opted in to text messaging were seven times more likely to become applicants than those who did not.Footnote2 St. Mary's customized these text messages based on where students were in the inquiry, application, or admissions process. A number of higher education institutions, such as Stanford, Princeton, and Duke, use text messaging for emergency alert notifications, which connect students to time-sensitive and potentially lifesaving information regardless of their location.Footnote3 A Middle Tennessee State University instructor uses text messaging to remind students about due dates and reading assignments and welcome students back from break periods.Footnote4 The time commitment involved with setting up this messaging strategy was low, taking a mere thirty minutes. It capitalized on the outcome of a study by Harley et al., which found that students were more likely to take immediate action in response to a text message even if the same information was provided through other mediums.Footnote5

Colleges and universities worldwide use mobile devices to varying degrees to communicate with, inform, support, and engage with students. GroupMe is a messaging tool for mobile devices that allows students to communicate with each other for group projects, share documents and photos, and create meetings.Footnote6 Gronseth and Hebert conducted a study to explore the use of GroupMe in face-to-face and online sections of a graduate course. Results indicated that GroupMe could stimulate collaboration between students and build connections beyond the individual course.Footnote7 Castleman and Meyer found a positive relationship between interactive text messaging and academic success for first-year students at West Virginia Colleges. Some of the messages sent to students were about advising and deadlines; others invited students to reach out if they were feeling overwhelmed and provided them with a way to contact the appropriate personnel at their institution.Footnote8

Understanding How CTU Students Use Messenger

When students don't understand or are frustrated with technology or other classroom elements, they are likely to send a message to their instructors first. To help with responses, CTU leaders realized that faculty needed access to the student view of the classroom. The CTU Messenger feature allowed faculty to better support students and provided faculty with insights into course design.

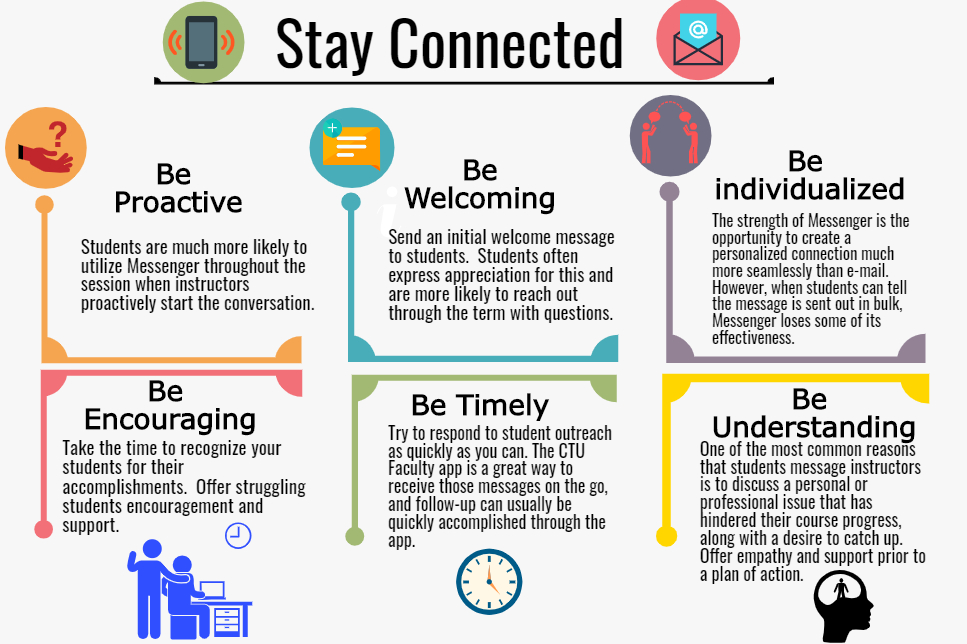

Students often share very personal stories of challenges and hardships with faculty and disclose serious health issues, family crises, and devastating losses. To further prepare faculty to respond effectively, CTU developed training and help guides to outline strategies for effective communication both in the classroom and through outreach.

Messages also provide a real-time understanding of how students interact with the LMS. Below are a few examples of messages from students to faculty, as well as associated insights.

"I am trying to post about me on the discussion board but cannot seem to find it."

Messages like this offer multiple insights into students' classroom experiences. First and foremost, these types of messages reflect students' issues with navigation. The students know they have work to do. They are ready to do the work. However, they cannot find where to put that work in the classroom.

"Yes, sir. I wanted to ask what assignments were due today . . . because it says one or two of my assignments are due today, but it doesn't say what it is, and I have already done my discussion board. Thank you."

This message tells us that the link between the assignment details and the area of the classroom to post the assignment, in this case the discussion board, is not intuitive.

We also see students turning first to their instructors for support in navigating the classroom, which indicates that the method for contacting the instructor in the classroom is intuitive.

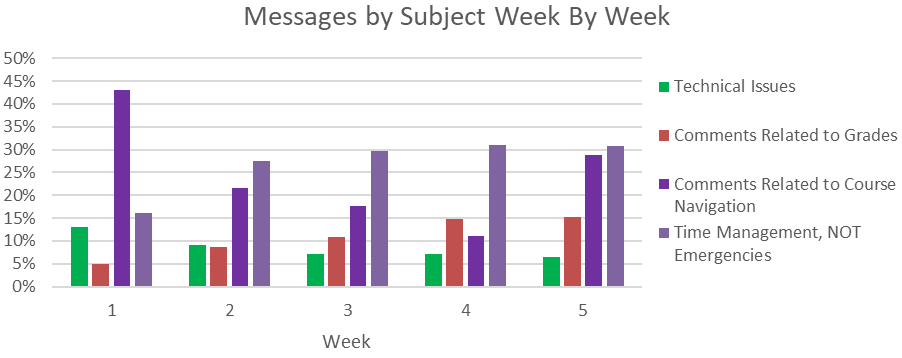

Students in CTU's general education courses frequently send messages related to course navigation issues at the start of the term and again at the end of the course as they complete their final assignments. For example, in the first week of the Academic and Career Success course, nearly half of the students' messages were related to challenges they were having with classroom navigation. This number decreased each week until the final week of the course when it spiked again (see figure 2). We can reasonably assume that the volume of messages is tied to the cadence of student work in the classroom: the first week when students are getting acclimated to the classroom and the final week when students are working to finish their assignments prior to the end of the session.

It is not uncommon to see messages like this: "Okay great. Sorry I missed the live chat I just gotten confused on the different time it's an hour ahead of my time. But I did re-watch it after it was finished."

In all of these examples, it is clear that students want to do the work regardless of acclimation to or challenges with the technology. These messages highlight students' strong desire to learn as well as their reliance on faculty as frontline support to help them figure out how and when to complete their work.

As shown in Figure 2, the number of technical issues and comments about classroom navigation decreases week after week, while grade-related questions and comments typically increase as the end of the term approaches. These trends point to the fact that as students become more familiar with the technology, they are able to focus more on course content.

Students' messages also provide insight into how they feel about their learning experience. Is a student feeling overwhelmed, discouraged, or empowered? Students express their emotions both explicitly and implicitly in the messages they send to faculty.

"I just took a look at your feedback from the discussion board post. . . . I apologize, I am usually really on top of things with my work, I am just struggling this month because we move at the end of the month, so we are down to the nitty-gritty with needing to pack up EVERYTHING, on top of still working full time and being six months pregnant. No excuse, I just wanted to let you know what I had going on and that I am not a poor student, just juggling A LOT right now."

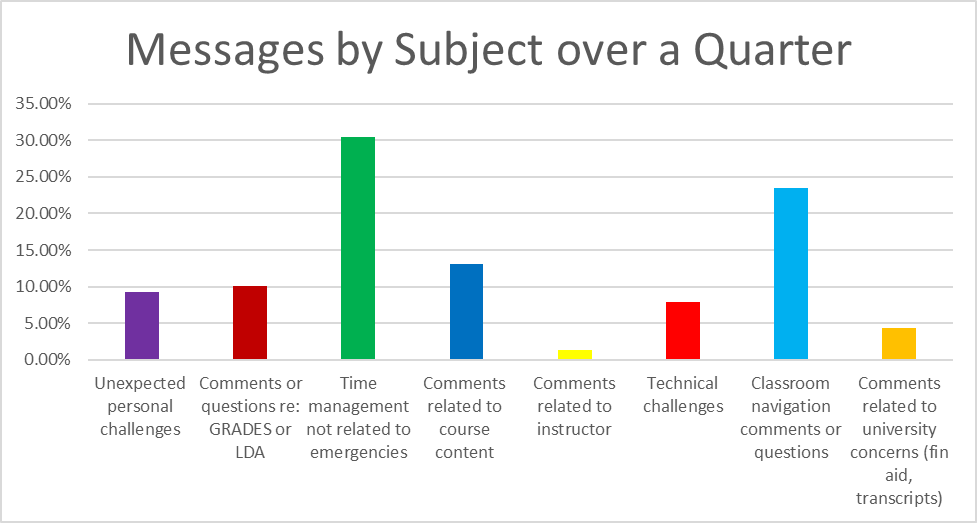

Messages from students dealing with time-management issues not related to an emergency consistently account for about a third of the messages students send about the challenges they are facing (see figure 3). For example, "I probably won't be able to be in any of the lives because I work two jobs, so my first job is 9-noon and the second one is 3-8 Tuesday through Saturday." And "I am sorry for missing the chat as my son was at football practice and the signal there isn't very good."

Some messages from students are affirming: "Thanks soo much. I am very motivated and excited about this new adventure."

Students' messages consistently demonstrate their intentions to prioritize school and successfully complete their coursework. Messages also provide CTU with unique insight into how students navigate disruptions.

When faculty and staff take advantage of these "messenger moments," they can personally encourage students to persist. Students acknowledge this outreach with messages like this: "Thank you so much. I really, really appreciated seeing that today. I'm in a downward spiral with no one supporting me in my decision to go to college. That really helped me. Thank you again."

When CTU Messenger communication is effective, initial data demonstrates that students are more likely to stay engaged instead of allowing the situation to derail their educational goals. The value in taking the time to engage with students to learn about what impacts them the most can make the difference between a student passing a course or failing it.

We believe this engagement is well worth the time and potentially can lead to improved student outcomes. We are excited to explore further insights and engagement opportunities as this work continues.

Notes

- Tashfeen Ahmad, "Mobile Phone Messaging to Increase Communication and Collaboration Within the University Community," Library Hi Tech News 36, no. 8 (October 2019): 7–11. Jump back to footnote 1 in the text.

- David Wallace Marshall, "Incorporating Texting into Your Communications Mix," College and University 86, no. 2 (2010): 57–62. Jump back to footnote 2 in the text.

- Ahmad, "Mobile Phone Messaging," 7–11. Jump back to footnote 3 in the text.

- Dianna Z. Rust, "Using Text Messaging Systems As a Class Communication Tool," College Teaching 66, no. 4 (October 2018): 222–224. Jump back to footnote 4 in the text.

- Dave Harley, et al., "Using Texting to Support Students' Transition to University," Innovations in Education and Teaching International 44, no. 3 (August 2007): 229–241; Rust, "Using Text Messaging Systems," 222–224. Jump back to footnote 5 in the text.

- Ibid. Jump back to footnote 6 in the text.

- Susie Gronseth and Waneta Hebert, "GroupMe: Investigating Use of Mobile Instant Messaging in Higher Education Courses," TechTrends 63, no. 1 (2019): 15–22. Jump back to footnote 7 in the text.

- Benjamin L. Castleman and Katharine E. Meyer, "Can Text Message Nudges Improve Academic Outcomes in College? Evidence from a West Virginia Initiative," The Review of Higher Education 43, no. 4 (Summer 2020): 1125–1165. Jump back to footnote 8 in the text.

Connie Johnson is Provost and Chief Academic Officer at Colorado Technical University.

Margaret Carmack is Executive Program Director for the College of General Education and Psychology at Colorado Technical University.

Tina Morrell is an Academic Librarian at Colorado Technical University.

© 2021 Connie Johnson, Margaret Carmack, and Tina Morrell. The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY 4.0 International License.