As cybersecurity professionals venture into a future of remote work and virtualized services, they must build on today's skills and develop new competencies for the future.

EDUCAUSE is helping institutional leaders, IT professionals, and other staff address their pressing challenges by gathering and sharing data. This report is based on an EDUCAUSE QuickPoll. QuickPolls enable us to rapidly gather, analyze, and share input from our community about specific emerging topics.Footnote1

The Challenge

In the 2021 EDUCAUSE Horizon Report | Information Security Edition, we imagined a future for higher ed cybersecurity characterized by sustained remote work, evolving security perimeters of endpoints stretching beyond the physical campus, and an increasing reliance on cloud-based solutions.Footnote2 It remains to be seen whether institutions will be equipped to meet these possible futures and, if so, what competencies cybersecurity professionals will need in order to thrive in that future. This QuickPoll aims to serve as a baseline of institutions' and cybersecurity professionals' future readiness, from which we may be able to chart a path forward.Footnote3

The Bottom Line

Evidence mounts that the post-pandemic future will retain some online/remote work options and will introduce new virtual demands for many higher education cybersecurity professionals. Institutions and cybersecurity teams are taking important steps now to prepare for that future, though areas of competency such as cloud vendor management are emerging as critical areas of growth for a cybersecurity workforce that will need to focus on evolving beyond the present-day landscape of tasks and skills.

The Data: The Remote Workforce of the Future

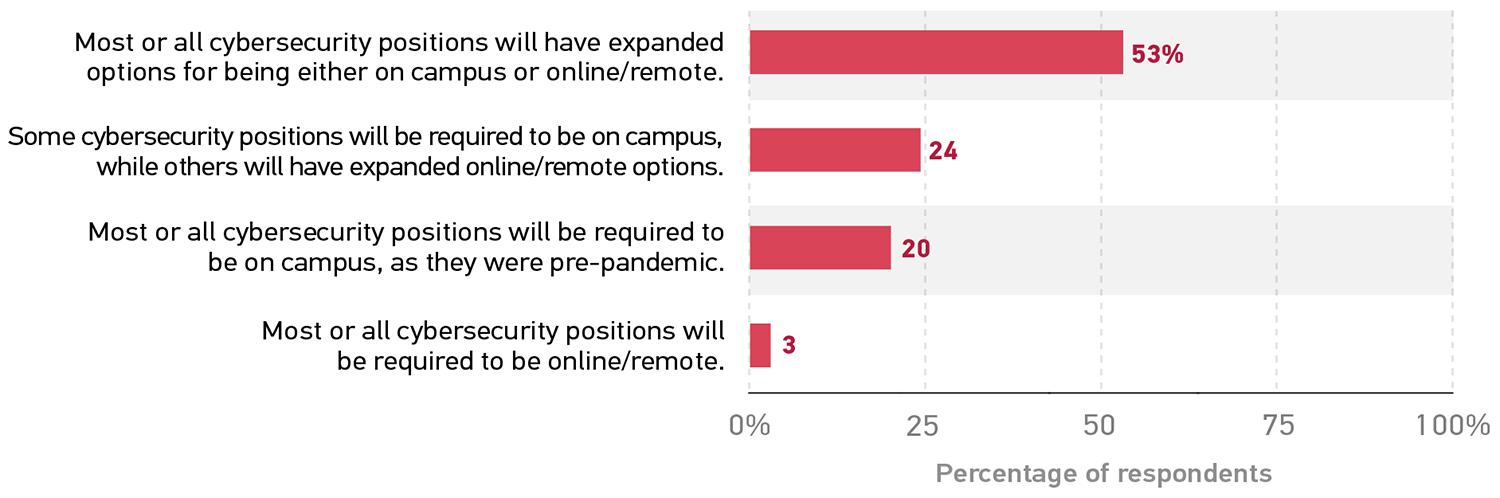

Evidence is emerging of a "new normal." Asked about their institutions' plans for online/remote work in the post-pandemic future, just over half of respondents (53%) anticipated that most or all cybersecurity positions at their institution will have expanded options for being either on campus or online/remote, while about another quarter (24%) anticipated that some positions will be on campus and that others will have expanded options (see figure 1). Respondents' observations and best guesses here may be lending further credence to notions that there will be some permanence to new ways of working in higher education. Indeed, only 20% of respondents anticipated that most or all cybersecurity positions would be required to be on campus, as they were pre-pandemic.

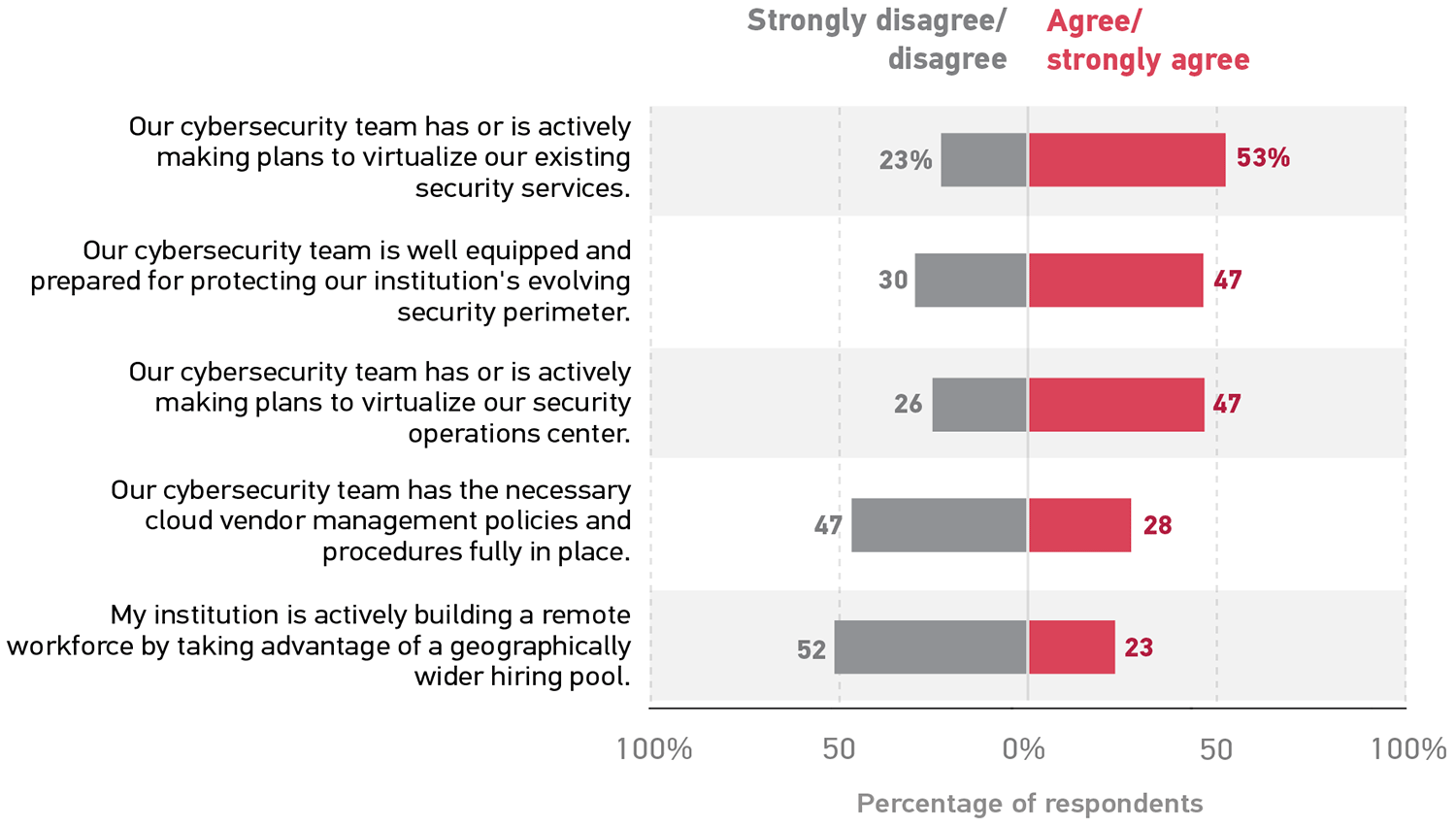

Work from home, as long as home is right here. Despite expectations of some residual online/remote work arrangements, only 23% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that their institution is actively building a remote workforce by taking advantage of a geographically wider hiring pool. It seems that although home or otherwise local remote work arrangements may be palatable for staff who are reasonably geographically accessible, being a more widely distributed organization may be a bridge too far for many institutions.

The Data: Plans and Capabilities for the Future

Institutions are preparing for the future. In some key areas, respondents expressed confidence that their institutions and cybersecurity teams are prepared to meet a future very different from the present. Institutions' security perimeters will continue to evolve as personal networks and devices used for work and learning become more numerous and scattered beyond the physical campus, and more respondents agreed (47%) than disagreed (30%) that their cybersecurity team is prepared to protect that evolving perimeter (see figure 2). Moreover, the majority of respondents agreed that their cybersecurity team has or is making plans to virtualize existing security services (53%), and nearly half agreed that they have or are making plans to virtualize their security operations center (47%).

The future is cloudy, but institutional planning may not be. Storm clouds may be on the horizon for some institutions, as their evolving perimeters and virtualized operations become increasingly dependent on cloud-based solutions they are ill prepared to manage. Less than a third of respondents (28%) agreed that their cybersecurity team has the necessary cloud vendor management policies and procedures fully in place. Presciently, our 2021 Information Security Horizon Panel earlier this year identified "cloud vendor management" as a key practice likely to have a significant impact on the future of higher education information security, lending further credence that this is a critical area of growth for the profession.Footnote4

The Data: The Cybersecurity Professional of the Future

Today's competencies are tomorrow's as well. Provided a list of key competencies, respondents were asked to select the three at which they currently are most proficient and the three that would be most important for their careers in five years (see table 1). Notably, the top-selected current competencies closely matched the top-selected future competencies, though in slightly different order and with the emergence of "using data for decision-making and planning" as an important future competency (selected by 27% as important in five years, compared to 21% currently).

Table 1. Top-Selected Competencies, Current and Future

| Rank | Current Competency | Future Competency |

|---|---|---|

|

1 |

Security program strategy development and leadership (46%) |

Security program strategy development and leadership (49%) |

|

2 |

Building relationships and networking with key stakeholders (41%) |

Security technical skills (36%) |

|

3 |

Security technical skills (37%) |

Risk management (36%) |

|

4 |

Risk management (37%) |

Building relationships and networking with key stakeholders (28%) |

|

5 |

Team/staff development and mentoring (23%) |

Using data for decision-making and planning (27%) |

To each their own (competencies). When selecting competencies that will be most important for their careers in five years, respondents' choices may be uniquely shaped by a mixture of their current career status, role, and personal aspirations for the future:

- Early-career professionals (0–9 years) view technical skills as important to their future far more than late-career (20+ years) professionals (at 54% and 26%, respectively). Late-career professionals, on the other hand, view using data for decision-making and planning as important to their career more than early-career professionals (at 33% and 21%, respectively).

- Manager-level staff view work/life balance and self-care as an important future competency more than do senior/VP-level staff (at 24% and 9%, respectively), while senior/VP-level staff view using data for decision-making and planning as having future importance far more than manager-level staff do (at 42% and 12%, respectively).

- Those pursuing a cybersecurity career outside of higher education view technical skills as important far more than those looking to advance to a more senior position in higher education in general (at 51% and 22%, respectively).

Institutional context matters. Differences in environment present cybersecurity professionals with a variety of challenges that may require the development of different skills for success. Cybersecurity teams at the smallest institutions, for example, appear to be more focused on building both their technical and strategic capabilities, perhaps because when the staff is small, individuals take on a balance of technical and strategic roles (see table 2). Teams at the largest institutions, on the other hand, may place more relative importance on building strategic relationships and taking advantage of institutional data to navigate their potentially more complex institutional environments.

Table 2. Top Future Competencies, by Institution FTE Size

| Institution Size (FTE) | Top Five Future Competencies |

|---|---|

|

Less than 2,500 FTE |

1. Security technical skills (65%) 2. Security program strategy development and leadership (63%) 3. Risk management (27%) 4. Setting goals and tracking outcomes (25%) 5. Using data for decision-making and planning (23%) |

|

2,500–4,999 |

1. Security program strategy development and leadership (48%) 2. Security technical skills (38%) 3. Risk management (35%) 4. Building relationships and networking with key stakeholders (27%) 5. (tie) Using data for decision-making and planning (21%) 5. (tie) Team/staff management (21%) |

|

5,000–9,999 |

1. Security program strategy development and leadership (44%) 2. Risk management (42%) 3. Security technical skills (34%) 4. Building relationships and networking with key stakeholders (31%) 5. Using data for decision-making and planning (27%) |

|

10,000 or more |

1. Security program strategy development and leadership (46%) 2. Risk management (37%) 3. Using data for decision-making and planning (30%) 4. Building relationships and networking with key stakeholders (29%) 5. Security technical skills (27%) |

Influence is a competency. Asked if there were additional competencies that would be important for the future, respondents most commonly reflected on the strategic influence of cybersecurity professionals within their larger institutional and higher education systems. Respondents expressed a desire to be tapped into the "bigger picture" and business needs of their institutions, and they identified the need for competencies in "storytelling," influencing their leadership and key stakeholders, and advocating for the importance of investing in security. Several respondents also highlighted emerging areas of importance such as privacy, cloud management, and certifications for keeping up with technical needs.

Common Challenges

It would be hard to argue that respondents' top competencies are not important for the future of cybersecurity—strategy development and leadership, technical skills, and risk management all matter. However, certain competencies that also clearly align with important challenges on the road ahead nevertheless received relatively lower importance ratings:

- Only 5% of respondents selected active listening as an important competency for the future. And yet practices that help facilitate empathy and understanding may only become more important for a profession grappling with mounting burnout and stress.Footnote5

- Only 6% of respondents selected vendor contract and relationship management as an important competency for the future. And yet few respondents think their team has the necessary cloud vendor management structures fully in place, even as they're looking to implement more virtualized services and online/remote modes of working.

- Just 13% of respondents selected cost/budget management as an important competency for the future. And yet we're all having to learn how to do more with less, and budgets may only continue to decrease from here.Footnote6

Promising Practices

What might our findings suggest for institutions'—and the larger industry's—strategies for building a cybersecurity workforce ready and capable for the future? Some general orientations to workforce development may find more traction and success than others:

- No two career pathways will look exactly alike. We know that factors such as career level, role, personal aspirations, and institutional context help shape the contours of a person's professional needs and interests. Workforce development efforts that provide personalized and non-prescriptive support, then, may be most appropriate for a profession yet evolving and charting its way forward.

- At first glance, the finding that respondents' current proficiencies match their expected most important future competencies may seem unsurprising and may even seem as it should be. But current proficiencies will work best for a future that resembles the present. An evolved future higher education, on the other hand, will demand an evolved workforce capable of effectively managing cloud vendor relationships, for example, or smartly navigating restricted budgets and exacting business needs. Approaches to workforce development fit only to the proficiencies of the present may be missing forward-thinking opportunities to build a workforce more prepared for meeting and shaping whatever future may be awaiting.

All QuickPoll results can be found on the EDUCAUSE QuickPolls web page. For more information and analysis about higher education IT research and data, please visit the EDUCAUSE Review EDUCAUSE Research Notes topic channel, as well as the EDUCAUSE Research web page.

Notes

- QuickPolls gather data in a single day instead of over several weeks, are distributed by EDUCAUSE staff to relevant EDUCAUSE Community Groups rather than via our enterprise survey infrastructure, and do not enable us to associate responses with specific institutions. Jump back to footnote 1 in the text.

- Brian Kelly, Mark McCormack, Jamie Reeves, D. Christopher Brooks, and John O'Brien, with Michael Corn, Steve Faehl, Emily Harris, Keir Novik, Sherry Pesino, Peter Romness, and Greg Sawyer, 2021 EDUCAUSE Horizon Report, Information Security Edition (Boulder, CO: EDUCAUSE, 2021). Jump back to footnote 2 in the text.

- The poll was conducted on May 11, 2021, consisted of 11 questions, and resulted in 326 responses. Poll invitations were sent to participants in EDUCAUSE community groups focused on IT leadership and cybersecurity. Our sample represents a range of institution types and FTE sizes, and most respondents (91%) represented US institutions. Jump back to footnote 3 in the text.

- See "Key Technologies & Practices" in the 2021 EDUCAUSE Horizon Report, Information Security Edition. Jump back to footnote 4 in the text.

- Juta Gurinaviciute, "Mental Health Warning in Cybersecurity: CISOs Across the Industry Reporting High Levels of Stress," Security Magazine, October 26, 2020. Jump back to footnote 5 in the text.

- Susan Grajek, "EDUCAUSE QuickPoll Results: IT Budgets, 2020–21," EDUCAUSE Review, October 2, 2020. Jump back to footnote 6 in the text.

Mark McCormack is Senior Director of Analytics & Research at EDUCAUSE.

© 2021 Mark McCormack. The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 International License.