Three undergraduate student researchers at the University of St. Thomas share the results of their study on students' experiences and perspectives during a global pandemic.

During the spring 2021 semester, many undergraduate students have been listening to lectures from their bedrooms while their instructors struggle to share their screens on Zoom. Class discussions are being held in randomized breakout rooms where sometimes not a single student turns on their camera or microphone. Hands-on interactive science labs have been turned into passive video-viewing sessions. Students may go through an entire school day without leaving their beds or having a single conversation.

The 2020–2021 academic year has presented challenges to students and professors alike. But what is learning actually like in the midst of a global pandemic? How do students feel about learning online, and what makes them feel satisfied with a course? As undergraduate senior STEM majors at the University of St. Thomas in Minnesota, we completed a research project that allowed us to contribute our personal insights and expand our academic understanding of learning during a pandemic.

Our Research Project

Our project was part of an elective psychology course on sensation and perception that we took in the fall of 2020. During a normal semester, the Sensation and Perception course includes a popular and exciting laboratory in which students conduct experiments on their ability to sense and perceive the world around them. Like so many other things, face-to-face courses and lab sessions pivoted to online delivery due to the coronavirus pandemic. In the new online version of the course, students were tasked with a revised project: to design and carry out a survey research project that would analyze higher education students' experiences and perspectives during a global pandemic. Our classmates tackled many different subjects that are important to students, such as changes in drinking habits, mental health assessments, and social visiting patterns. Inspired by our own personal disappointments with our academic experiences after the emergency move to remote learning in March 2020, our group chose to explore the topic of student satisfaction with learning experiences to see how other students felt during this time.

The vast majority of previous research has not found a significant difference in teaching outcomes between distance and face-to-face learning.Footnote1 However, the results of those studies may be skewed due to inherent selection bias. Before the pandemic, students could choose their courses based on learning preference. Some students sought out online classes because they fit better with their personalities or schedules. Likewise, before the pandemic, instructors could choose a teaching modality that reflected their comfort and skill with online technology. But in March 2020, everything changed. Faculty at our university had less than one week to make the switch from face-to-face classes to emergency remote learning. Overnight, students went from having an active university social life to doing schoolwork from their childhood bedrooms or isolated in sparsely populated college dorm rooms. Some students had limited access to necessary resources for online learning, like the regular use of a computer, reliable Wi-Fi, and a printer. Early reports of remote learning during the spring 2020 semester showed lower rates of student satisfaction. Students noted instructors' lack of preparedness for online course delivery.Footnote2 This isn't surprising, as many students and instructors had no online learning or teaching experience prior to the emergence of COVID-19.Footnote3

After the end of the spring 2020 semester, plans for the 2020–2021 academic year remained uncertain. Would there be a return to campus for fully face-to-face courses? Would courses remain online? Or, would there be something in between, like hybrid or blended courses? Many instructors at St. Thomas took digital course design workshops during the summer. Nationally, some universities kept classes face-to-face but implemented mask mandates and social-distancing regulations that dramatically changed the classroom dynamic. Others switched to online course delivery only. Would the additional training and time to prepare make a difference in satisfaction for students taking online courses? For our research project, we set out to explore two main questions:

- What type of classroom learning environment were students most satisfied with: online, face-to-face, or blended?

- What specific course-design factors might impact student satisfaction levels?

To answer these questions, we created a survey of student satisfaction levels adapted from San Joon Lee et al.'s survey instrument, which uses a five-point Likert scale to assess three areas of learning support: instructional, peer, and technical.Footnote4 Overall, 240 undergraduate students responded to our survey via social media or Amazon Mechanical Turk. Respondents included students from private (59%) and public (41%) institutions who were in their first through fifth year of undergraduate education. First, we compared student satisfaction levels across learning modalities: online only, face-to-face, or blended (60% of the respondents were enrolled in online only courses, 11% were in face-to-face courses, and 29% were in blended courses). Next, we used regression analysis to determine which elements of course design and implementation best predicted students' satisfaction.

Major Findings

Based on our own and our peers' disappointment with the quality of online learning in spring 2020, we hypothesized that there would be a difference in student satisfaction levels across the three modalities. We predicted that face-to-face learning would have the highest level of student satisfaction and online would have the lowest. However, the data showed otherwise. Even when students had no choice but to enroll in the format their school was offering, there was not a significant difference in overall student satisfaction levels across the three learning modalities. When asked to rank their level of agreement with the statement "Overall, I liked the course," students' average endorsement scores ranged between "neither agree nor disagree" and "somewhat agree" (see table 1).

Table 1. Average Student Satisfaction Scores (1=Strongly Disagree; 5=Strongly Agree; individual item scores are listed in table 2.)

| Online | 2.6 |

| Hybrid | 2.5 |

| In-Person | 2.7 |

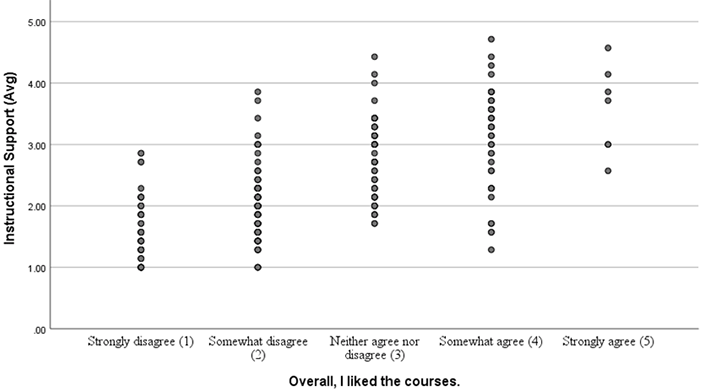

If learning modality didn't impact student satisfaction levels, what did? We used regression analysis to determine what types of support (instructional, technical, or peer) contributed the most to overall student satisfaction levels. From those three categories, instructional support had the biggest impact on student satisfaction (r=.67, see figure 1). Students were most satisfied with their courses when they had professors who were available to them, clarified the steps in the learning process (e.g., goals, expectations, assessment criteria), and provided helpful feedback on assignments.

After discovering that instructional support was the largest predictor of student satisfaction, we decided to take a deeper dive to discover what specific factors (among thirteen choices) contributed the most to student satisfaction levels (see table 2). Using a multiple regression analysis, we determined that the factor that contributed the most was whether the students felt they had achieved the learning objectives. This factor alone accounted for 37% of how much students enjoyed their classes. Participating in valuable group discussions was the second most important predictor of student satisfaction levels, accounting for an additional 11% of variance.

Table 2. Student Satisfaction Survey Results*

|

|

Online | Hybrid | Face-to-Face |

|---|---|---|---|

| Instructional support | |||

|

The course goals/objectives were clearly outlined. |

71% |

63% |

67% |

|

I know what I was expected to accomplish each week. |

68% |

68% |

59% |

|

Instructors provided clear instructions for assignments. |

68% |

57% |

79% |

|

The feedback on the assignments was helpful. |

61% |

64% |

52% |

|

I felt that I could ask any questions regarding the course materials. |

59% |

53% |

58% |

|

I felt that instructors were easily accessible. |

59% |

57% |

52% |

|

The instructors encouraged students to be successful. |

74% |

64% |

63% |

| Peer support | |||

|

I enjoyed the group discussions. |

50% |

34% |

48% |

|

There were many opportunities to interact with peers. |

41% |

35% |

44% |

| Technical support | |||

|

I felt like I could overcome technical issues. |

56% |

56% |

59% |

|

I knew where to ask for help when I had any technical issues. |

58% |

58% |

63% |

|

I felt that I could get technical support when I needed. |

50% |

49% |

63% |

| Overall evaluation | |||

|

I felt I achieved the learning objectives. |

57% |

52% |

54% |

|

Overall, I liked the courses. |

60% |

53% |

63% |

Commentary

Our experiences as students informed our interpretation of the findings. From a student perspective, having a clear syllabus is a foundational aspect of good instructional support. An effective syllabus clearly states what the assignments are and when they are due, how much each assignment contributes to the final grade, and what resources are needed for each assignment. If assignments within the course are designed with enough transparency, students should be able to figure out what to do and how to do it and gain a sense of achievement from the process. Based on our personal experience and from talking with others, we have observed that students often don't read the learning objectives section in the syllabus, so we were surprised that achieving the learning objectives was so important in predicting overall course satisfaction. However, having clear set of expectations and being able to access the tools needed to accomplish tasks contributes to student understanding and self-efficacy.

Instructor availability and consistent communication are also essential elements of instructional support. During times when so many are things changing, keeping the syllabus and course website updated is critical. For example, mentioning that a deadline has changed during the lecture only isn't enough; those changes also need to be reflected in the syllabus and on the course website. Without these updates, assignments may slip through the cracks. The ability to answer questions swiftly via email is also important to instructional support. Perhaps faculty who struggle to respond to student emails could use a communication app like Remind to help them respond to student queries in a faster and more informal way. Prompt communication takes on greater relevance when students have additional demands on their time. During the coronavirus pandemic, many students have taken on additional jobs and family and caregiving responsibilities, so dropping into instructors' allotted weekly office hours has become more unlikely.

Our analysis showed that participating in valuable group discussions was the second most important predictor of student satisfaction. As most students and teachers can attest, students commonly leave their cameras turned off during synchronous online classes. Doing so makes connecting with the instructor and other students more difficult. In a traditional classroom setting, college students go to class each day, sit in "their" seat, and talk to those around them, creating an easy camaraderie for think/pair/share exercises. In the current era, students are told to talk to a random selection of their classmates in online breakout rooms. This type of social interaction can be great for some extroverted students, but for more introverted or socially anxious students, it can be daunting. Starting every new breakout group with an ice-breaker activity can really help students feel comfortable in the virtual space. Then, the newly formed group can feel more at ease when talking about the assigned topic, especially if it is one that is not easily understood. Additionally, it helps when instructors identify the specific goals of the breakout-room discussion in the chat and ask students to create a product, like a slide of major ideas, to share back with the larger group. Without ongoing facilitation, students often don't know what they are supposed to discuss, so the conversation wanders or just goes silent.

Going Beyond COVID-19

Our research gave us a better understanding of the factors that have contributed to student satisfaction during the coronavirus pandemic. We found that students are most satisfied with their courses when they feel supported by their instructors and when they feel that they have achieved the learning objectives of the course. We also learned that one way to improve student satisfaction is to incorporate quality group discussions during class. Although our research was informed by educational experiences during the coronavirus pandemic, many of our findings can be used to improve educational experiences after the pandemic, regardless of the course format.

For related information, see the EDUCAUSE research reports Student Experiences Learning with Technology in the Pandemic (April 2021) and Student Experiences with Connectivity and Technology in the Pandemic (April 2021), as well as the infographic "Keeping Students in the Loop: Fall 2020 Students on Courses and Connectivity."

Notes

- Tuan Nguyen, "The Effectiveness of Online Learning: Beyond No Significant Difference and Future Horizons," MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching 11, no. 2, (June 2015): 309–319. Jump back to footnote 1 in the text.

- Sahar Abbasi, Tahera Ayoob, Abdul Malik, and Shabnam Iqbal Memon, "Perceptions of Students Regarding E-Learning during Covid-19 at a Private Medical College," Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences 36, COVID-19 suppl. 4 (May 2020): S57–S61. Jump back to footnote 2 in the text.

- Mohammed H. Rajab and Abdalla M. Gazal, "Challenges to Online Medical Education during the COVID-19 Pandemic," Cureus 12 no. 7 (July 2020). Jump back to footnote 3 in the text.

- Sang Joon Lee, et al., "Examining the Relationship among Student Perception of Support, Course Satisfaction, and Learning Outcomes in Online Learning," The Internet and Higher Education 14, no. 3 (July 2011): 158–163. Jump back to footnote 4 in the text.

Madison Foerderer is a psychology major at the University of St. Thomas.

Sarah Hoffman is a neuroscience major at the University of St. Thomas.

Natalie Schneider is a neuroscience major at the University of St. Thomas.

J. Roxanne Prichard is a professor of psychology at the University of St. Thomas.

© 2021 Madison Foerderer, Sarah Hoffman, Natalie Schneider, and J. Roxanne Prichard. The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY 4.0 International License.