The construction of a new medical education building provided an opportunity for the Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine to reimagine its learning spaces and rethink the technology supporting its active learning curriculum.

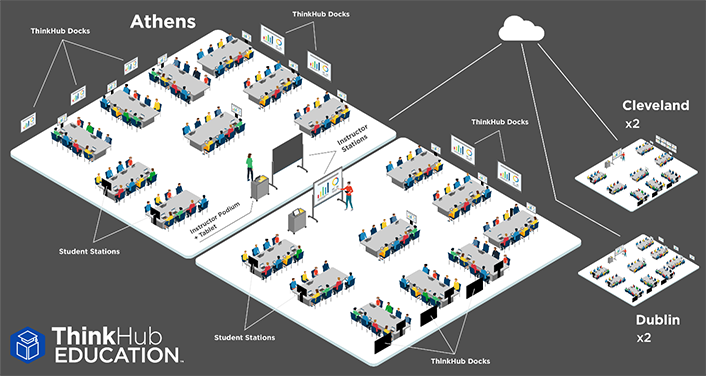

Over the past several years, the Ohio University Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine (the Heritage College) has grown significantly. A generous, multimillion-dollar gift from the Ohio Heritage Foundation (OHF) allowed the Heritage College to double its enrollment over the past six years and add two new campuses in Cleveland and Dublin to its original campus in Athens, Ohio (see figure 1). The gift also allowed the Heritage College to revamp and launch a new active learning curriculum, the Pathways to Health and Wellness Curriculum (PHWC). In 2019, the Heritage College began the design and construction of a $65 million medical education space in Athens as an initiative of the OHF gift. The design drivers for this space were supporting the modern medical education of osteopathic physicians, creating a flexible space, and ensuring connectivity to the Cleveland and Dublin campuses, our clinical partners, and the broader health care community across the state of Ohio.

The construction of the new medical education building provided an opportunity to rethink the technology supporting the active learning curriculum at the Heritage College. Because the active learning curriculum depends on all three campuses being able to connect with each other so that they can complete learning activities together, the technology at the Heritage College required significant support from the technology team and room-based hardware systems that connected classrooms via a videoconferencing bridge. Increased engagement between faculty and students was a priority during the design and construction processes. Extending the faculty and student experience across all three campuses and virtual learning spaces was crucial. Ensuring a learner-centered experience was at the core of the learning space design and technology selections.

Transformed Learning Spaces

The educational system is undergoing gradual changes, and learning environments have to be adapted to reflect the dynamic and changing reality in which we live.Footnote1 The health care and medical education environments are not excluded from these changes. Training future physicians to adapt to and assimilate information from multiple interprofessional and technological sources to inform their clinical decision-making is increasingly important. Providing a transformational educational experience requires a transformation of the educational space. Traditional classroom settings are designed for factory-style learning, which perhaps could have supported the health care environment in the past.Footnote2 However, traditional classrooms are not a viable solution for educating the modern-day health care workforce. "[A] need for learning spaces that can support learner-centered instruction in a technology- and information-rich twenty-first-century environment exists," explained Omolola A. Adedokun et al. in the article "Student Perceptions of a 21st Century Learning Space."Footnote3 Thus, the design team considered options for learning spaces that support learner-centered instruction and the needs of a technology and information-rich twenty-first-century workforce.

As a part of the new Heritage College learning space design for all campuses, the team crafted the requirements to support the active learning principles of the newly established PHWC. Generally, the design and development of new learning spaces are informed by user input, existing learning spaces at other institutions, and industry post-occupancy surveys and interviews rather than research on the impact of learning spaces on teaching and learning processes and outcomes.Footnote4 To focus on the importance of pedagogy and achieve maximum flexibility and faculty-student engagement in the design, the learning space design and development process for the Heritage College involved many opportunities for input (via in-person sessions, surveys, etc.) from clinical and non-clinical faculty. Members of the technology and design teams also participated in learning activities to understand how instructors historically taught content and implemented innovative pedagogical practices in outdated spaces. The design team researched how the active learning curriculum for medical education was being facilitated in a traditional, lecture-based learning environment.

Whether digital or physical, learning spaces are the most important contemporary infrastructure requirement for learning in the twenty-first century. While more physical spaces are not needed in higher education, increased flexibility in available spaces is desired.Footnote5 Future learning spaces (FLSs) are touted for their capacity to promote collaborative learning experiences through open, flexible, and diverse designs that combine physical and digital infrastructure.Footnote6 As the Heritage College team considered designs for the learning spaces in the new medical education building, ensuring a consistent learner experience at the Cleveland and Dublin campuses was a priority. Because all learning activities are connected between the three campuses and their associated student cohorts, a student-centered, active learning classroom (ALC) design process ensued.

Student-Centered, Active Learning Classroom Design

Active learning spaces (ALSs) are not a novel concept in classroom design. In the early 1990s, the Student-Centered Active Learning Environment with Upside-down Pedagogies (SCALE-UP) learning model was introduced. As described by Colin Loughlin et al., students in SCALE-UP classrooms sit in groups at round tables, and each table has a shared laptop. The instructor lectern is "placed centrally, and wall-mounted [video] displays are placed at intervals around the room." The instructor moves from table to table, monitoring progress and answering questions during short tasks and activities. The Technology Enabled Active Learning (TEAL) project from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) built on the SCALE-UP model, but it placed "much greater emphasis on technology-mediated communication, visualizations, animations, and interactions . . . ."Footnote7 Typically, ALCs use movable work surfaces that are grouped in pods. The pods do not usually face the front of the classroom; they are designed to increase access to technology and create workspaces that allow for student interaction. TEAL classrooms often include whiteboards that facilitate group problem-solving and peer-to-peer teaching.Footnote8

At the Heritage College, a form of active learning was already happening at the Cleveland and Dublin campuses. The Cleveland and Dublin learning spaces were outfitted with student "pod" stations, which comprised fixed tables connected to an assortment of display, audio, and video hardware (see figure 2). The spaces also had videoconferencing capabilities to allow for connectivity with the Athens campus, which had lecture-hall style classrooms (see figure 3). ALSs are designed to be flexible, student-centric teaching environments with embedded technology that enables twenty-first-century pedagogies. The emphasis is on interactive and social constructivist methods that encourage group activities and peer interactions.Footnote9 Some spaces in the Heritage College looked like ALCs, but they did not foster the constructivist and collaborative nature of the PHWC.

The Heritage College faculty noted that student-centered design and engagement were among their top priorities for space design. While the faculty insisted on a departure from traditional learning spaces, a few instructors were cautious of highly complex technology spaces. Some studies of technology-rich learning environments have reported positive outcomes related to active learning compared to traditional didactic classrooms; other studies have reported no benefits or have found that the technology interrupts or distracts from learning.Footnote10 However, due to the nature of the medical education curriculum and its focus on team-based learning through weekly case presentations, most faculty were supportive of an active-learning approach to space design. Research suggests that perceptions of student engagement among instructors who follow a more constructivist teaching philosophy are significantly higher when those instructors move from a traditional classroom to an ALC. This finding implies that constructivist instructors are either better able to use the ALC to support student engagement or are predisposed to perceive increased student engagement in the ALC.Footnote11

Another important requirement for the new Heritage College learning spaces was flexibility; the spaces would need to accommodate different types of teaching and nonacademic uses. Some studies of technology-rich learning environments have reported that a flexible classroom can be difficult to achieve. At the Heritage College, creating this highly flexible space meant that we had to be very intentional with every aspect of the room, including technology and furniture selection and placement. Research indicates that emphasizing flexible, technology-enhanced classrooms equipped with portable and aesthetic furniture invites active, student-focused, collaborative learning.Footnote12 Research studies also suggest that the teaching environment should be flexible enough to meet the needs of multiple disciplines and interprofessional learning if it is to be considered an essential learning environment.Footnote13 The group of instructors at the Heritage College agreed that flexible learning spaces would accommodate current pedagogical practices and future teaching methods. Therefore, not only would the furniture need to be flexible, but the technology would need to allow for various teaching and learning styles and also be able to meet the needs of those who may not be in the physical classroom.

Active Learning versus Future Learning

Designing physical spaces to support classroom-based learning can seem like a counterintuitive effort as modern higher education is constantly being transformed and challenged. The popularity of virtual learning has diminished the need for a large number of traditional classroom spaces. This trend grew in 2020 and 2021 when nearly all higher education activities shifted to a virtual format due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, a need exists to reimagine physical classroom spaces in ways that will "future-proof" them and allow them to stand the test of time (e.g., by building flexibility into the design). According to a report authored by Alexander Freeman, Samantha Adams Becker, and Michelle Cummins, learning spaces must be reimagined to reflect an emergent reality in K-12 and higher education. Future learning spaces (FLSs) should combine pedagogy and technology to facilitate versatile teaching and collaborative and interactive learning.Footnote14 Learners in FLSs can share responsibility for the content, technology, and space. Additionally, an FLS puts learners at the center; learning is perceived as a social process.Footnote15

FLSs or ALCs facilitate interactions among students who work collaboratively on tasks that are of interest to them. Movable furnishings and other features enable students to use the space to meet instructional goals that correspond with twenty-first-century skills. One ALC learning goal is building knowledge through the use of mobile and interactive technologies.Footnote16 The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) describes innovative learning environments (ILEs) and modern learning environments (MLE) as powerful, physical, social, and pedagogical learning contexts that enable learners to thrive in the twenty-first century.Footnote17 Referencing Yotam Hod's 2017 article on FLSs in schools, Michael Rook et al. wrote that "FLSs blend the latest in architectural advances for space design (e.g., modern, flexible furniture within collaborative environments that provide bring‐your‐own‐device [BYOD] connectivity) and advances in perspectives on learning and instruction (e.g., situated learning, distributed cognition, learning communities, knowledge building, collective inquiry)."Footnote18

With pedagogical requirements in mind, the Heritage College set out to challenge the boundaries of traditional hardware-based, audio-visual (AV) classroom design to promote a technology design that would be scalable and adaptable for years to come. The Heritage College worked with T1V Inc. and ROOT Integrated Systems to deploy a software-based solution, ThinkHub Education and ThinkHub MultiSite, to provide the backbone for the function and control of the college's learning spaces. The ThinkHub system uses software to connect the instructor and student across all three campuses via four modalities (see figure 4):

- Instructor stations at each campus (connected via MultiSite collaboration software)

- Student stations at each campus (accessible by any campus' instructor station)

- The instructor's device (can be located anywhere in the physical or virtual space)

- A MultiSite server that combines and controls the feeds from all the inputs

This technology is integrated into the existing hardware-based AV environment, including video/web conferencing, room audio, and wall-display solutions. Customizing the software in the physical space has transformed the impact of the experience. Getting beyond cataloging the physical space and the activities that happen there and focusing on the essence of users' experiences can illuminate how the space subtly contributes to learning contexts.Footnote19

In addition to a future-proof physical environment, it was also important for the Heritage College to consider the future of learning as the physical and virtual worlds collide in medical education. For example, training in telehealth needs to be a viable option for portions of the medical education curriculum since the health care industry provides and promotes this service. The HyFlex (hybrid-flexible) course design model combines physical and virtual spaces and face-to-face and online learning.Footnote20 Supporting participants, students, and instructors in joining the learning activity physically or virtually and ensuring that everyone has a similar experience were essential parts of future-proofing our learning space design.

The Impact of Learning Space Design on Physician Education

Overhauling and redesigning learning spaces and technology require significant investments of money, time, people, and space (among other things); therefore, considering how the learning space contributes to a person's success as a student and, ultimately, as a physician is crucial. According to Kimberly Sawers et al., "[c]oncerns about failure rates, low conceptual understanding, and high absenteeism are all reasons why colleges and universities have looked for alternatives to traditional lectures as the primary mode of instruction."Footnote21 A case study conducted by Rebecca Donkin and Mary Kynn revealed that the learning space can impact engagement, with most students (77 percent) indicating that the collaboration studio (like an active learning space) motivated them to learn.Footnote22 Team classroom techniques encourage learner interdependence as a way of fostering cognitive and social development. The outcome of collaborative learning is for students to construct new problem-solving knowledge by accomplishing a task together.Footnote23 In medical education, providing teams with a safe environment to discuss a virtual patient and work through a clinical case helps them develop communication, professional inquiry, critical thinking, and motivational skills without the potential stress and cognitive demands of working with a real patient in a clinical setting.Footnote24

Health care is largely a team-based profession. Throughout their education, future physicians will work among interprofessional teams to assess, diagnose, and treat patients in a clinical setting. Fostering teamwork and collaboration in a learning space further solidifies the importance and quality of training for students as they prepare to enter the world as physicians. The discourse of twenty-first-century learning emphasizes the alignment of education and workplace practices. Therefore, the design of these innovative learning environments (ILE) facilitates the sort of human interactions we would expect to see in modern workplaces.Footnote25 Working together is the basis for creativity and innovation in every field and constitutes part of daily activity.Footnote26 However, working sporadically in teams does not result in effective team-based education. At least forty hours of teamwork are required to promote team formation, productivity, and peer learning.Footnote27 In addition, research suggests that learning improves significantly when teams work together for more than ten hours, as evidenced by improved grades. This amount of time is necessary for team members to become familiar with the space and technology and for social constructs to fully develop. This does not seem to occur in a standard classroom, so it appears that the space in which students learn matters.Footnote28

As the Heritage College team considered the design of the learning spaces, they needed to understand the emphasis on team-based learning within the curriculum. One of the central tenants of the PHWC is producing team-based generalists who share the following characteristics:

- Actively participate as members of interprofessional health care teams

- Work well with other specialists in co-managing patients appropriately

- Demonstrate competence in a broad array of clinical areas yet acknowledge their own limitations

- Recognize strengths in other team members when choosing whether to lead or followFootnote29

The Heritage College learning spaces were designed centrally around the student team and the instructor. Each student station includes a table that accommodates eight students and is assigned to a mobile T1V student station equipped with a retractable microphone (see figures 5 and 6). The station provides wireless device capability and annotation for group-based work, as well as a display to facilitate the exchange of ideas across groups at different campuses. The instructor has BYOD technology that allows for wireless display. In addition, the classroom designs support connectivity to multiple classrooms and engagement with the instructor/student stations through the ThinkHub Education and MultiSite solutions. An instructor based in Athens can engage with students in Dublin or Cleveland simply by bringing up their student stations on the screen. The learning environment also invites remote participants through a web conferencing integration. By providing a learning philosophy and a learning space that supports that philosophy, the Heritage College design promotes teamwork, collaboration, and cooperation to facilitate the highest possible learning outcomes. These outcomes will result in physicians who are more than adequately prepared to be highly effective in a physical or virtual team-based work environment, contributing to their professional success.

Barriers to Future Learning Space Design

Although many instructors were excited about the opportunity to teach in a space specifically designed for teamwork and collaboration, a few instructors wanted to ensure that minimal effort would be required to understand the technology concept for the new learning spaces. Some educators believe that technology should have little to no impact on learning outcomes or the student experience. Although this mentality could be considered a barrier to the design and use of the learning space, the Heritage College design team viewed it as an opportunity to promote the need for a flexible learning space.

One aspect of teaching philosophy is the degree to which an instructor's views align with a constructivist approach. A constructivist approach is student-centered and is based on the expectation that knowledge is developed or created through experience. On the other end of the spectrum is the traditionalist approach, which is teacher-centered and based on the expectation that knowledge and skills are transmitted from the instructor to the student.Footnote30 In their quasi-experimental study, Sawers et al. found that instructors perceived students to be significantly more engaged in an ALC than in a traditional classroom; this perception was substantially higher for instructors with a constructivist philosophy. In addition, when in a traditional classroom setting, instructors' teaching philosophies influenced their behavior but not their perceptions of student engagement. Conversely, when in the ALC, instructors' teaching philosophies influenced both their behavior and their perceptions of student engagement. The researchers "found that instructors' behavior mediates the relationship between teaching philosophy and student engagement."Footnote31

As space and technology are continually evolving, there will be increasing pressure for instructors to adjust their teaching styles to promote optimal learning outcomes for their students. As previously discussed, the Heritage College design team recognized that a small number of instructors were hesitant to use the technology. This concern was addressed by ensuring that the space design allowed for minimal technology use and by helping instructors use the technology if required (see figure 7). This approach helped instructors feel comfortable using their existing teaching methods while learning to use the new technology over time. The extent to which students are engaged with and have positive learning experiences is highly dependent upon learning space design, instructional content, and facilitation methods.

A significant amount of research suggests the coupling of innovative pedagogies with FLSs results in a positive learning experience that promotes teamwork and collaboration. However, for many higher education institutions, the cost of upgrading or creating FLSs is prohibitive. One reason that purpose-built technology spaces are rare is that they require a large investment by the education sector and its staff. Not only is the cost of purchasing technology a consideration, training and motivating staff and students to use the technology are as well.Footnote32 Some research suggests that funding will be a central issue to learning space design. In their 2017 paper presentation on ALSs and the flipped classroom model, Colin Loughlin et al. noted that "as more students benefit from using ALSs, demand from staff and students will probably start to ease the purse strings.Footnote33 While there is general agreement that ALSs are desirable and most institutions have converted some classrooms or lecture theatres (or plan to do so), a critical mass has not yet been reached. ALSs are still relatively low on the agenda for most cash-strapped higher education institutions, and there are no examples of ALS implementations across an entire institution. The actual benefits cannot be accessed until there has been a large-scale higher education adoption of ALSs.Footnote34

At the Heritage College, the design team considered several factors to justify the investment in the newly designed spaces. The fact that the spaces were software-centric allowed for greater flexibility, meaning that the college could reduce the need for a variety of physical spaces to accommodate different needs. A learning space could be transformed into a didactic or lecture-based space, an event space, an ALS, or a student group space. Having a smaller physical footprint allowed the team to invest more heavily into the flexibility of the spaces.

Administrators may also be hesitant to fund physical learning spaces due to the unknown impact of COVID-19 and the shift to virtual learning. As many higher education institutions are moving more coursework online, the need for highly technical classroom environments is a questionable one. In addition, higher education institutions are suffering financial losses due to the massive shift of students from in-person to online learning and the resulting loss in ancillary income from on-campus students. On the other hand, the dilapidation of learning spaces could negatively impact an institution's recruitment efforts and a student's decision to enroll in a particular program based on the availability of in-person learning. Educators should begin thinking of learning spaces—physical and remote—as a combined investment in the future of the institution and the outcomes of its students. Space is and will continue to be an important factor in education and learning outcomes for students.

Limitations in Research

Research on understanding the impact of learning space design on students' experiences and student collaboration is minimal. Researchers generally do not clearly delineate the type of learning space used in their research. A recent study comparing student performance in a traditional lecture classroom and a technology-enhanced ALC showed that the students in the ALC performed better than their peers in the traditional classroom. However, this study does not address whether a specific type of ALC is more conducive to social constructivist learning or if any ALC would suffice.Footnote35 In their investigation into how teaching philosophy and learning space influence instructors' perceptions of student engagement, Sawers et al. noted that while "lecture was the predominant instructor strategy used in the traditional classroom, a wider variety of teaching strategies was utilized in the ALC, such as problem-based exercises, team-based projects, interactive assignments, and think-pair-share. . . . [T]he findings of these studies indicate that the type of classroom influenced student learning outcomes (e.g., failure rates) and student satisfaction (e.g., attitudes, attendance); however, it is difficult to know what was driving the results. Were they due to a change in the learning space, the curriculum, or the instructor's behavior" (or, potentially, a combination of these things)?Footnote36

The Heritage College invited its first cohort of students into the newly designed learning spaces in the fall 2021 semester. Thus, we have not yet had the opportunity to research how the design of software-centric, MultiSite-connected FLSs contribute to medical education students' experiences and collaboration and impact their success and learning outcomes. Future research may include an assessment of self-reported student experiences in different learning spaces. Another research topic that warrants further study is whether and how instructors changed their teaching style or pedagogy because of the space and their use of it. For example, Heritage College faculty could be surveyed on their experience in learning environments (traditional, virtual, FLSs) before the pandemic, during the pandemic, and after the pandemic. The impact of a HyFlex environment on an instructor's teaching methodologies could also be explored.

Conclusion

Research confirms that learning spaces are a key component of the instructor and student experience. A technology-rich collaborative space can improve explicit learning outcomes, such as grades on student assessments, and assist with the development of implicit outcomes, such as engagement, communication, motivation, and professionalism.Footnote37 Adedokun et al. found that over 90 percent of students felt that the twenty-first-century learning space was better than a traditional classroom at supporting collaborative learning, instructor-student interactions, and student comfort. More than two-thirds of students felt that the twenty-first-century learning space was better than a traditional classroom at supporting student-student interactions, student learning, student interest in attending their courses, and students' motivation to learn.Footnote38 The learning space cannot independently change student motivation and learning; however, students reported that the twenty-first-century learning space had a larger impact on their motivation than it did on their learning.Footnote39 While their aspirations for the spaces themselves were not necessarily ambitious, a large proportion of educators are already engaging with the social constructivist pedagogies that will reap the most rewards if and when ALSs become commonplace.Footnote40

In addition to understanding how learning spaces influence student engagement, understanding how learning spaces impact medical education pedagogy is crucial. For the Heritage College, the role the learning space plays in creating successful physicians who are proficient in the content and possess the skills necessary to work collectively with an interprofessional team is not yet known. However, research indicates that learning spaces will likely continue to be used in higher education institutions. As with all things, teachers, students, space, content, and technology will continue to evolve.

Notes

- Kimberly M. Sawers et al., "What Drives Student Engagement: Is it Learning Space, Instructor Behavior, or Teaching Philosophy?" Journal of Learning Spaces 5, no. 2 (2016): 26–38. Jump back to footnote 1 in the text.

- Dianne Smardon, Jennifer Charteris, and Emily Nelson, "Principals' and Teachers' Perceptions of Innovative Learning Environments," Teachers' Work 12, no. 2 (2015): 149–171. Jump back to footnote 2 in the text.

- Amolola Adedokun et al., "Student Perceptions of a 21st Century Learning Space," Journal of Learning Spaces 6, no. 1 (2017): 1–13. Jump back to footnote 3 in the text.

- Ibid. Jump back to footnote 4 in the text.

- Ibid. Jump back to footnote 5 in the text.

- Michael M. Rook et al. "Forming and Sustaining a Learning Community and Developing Implicit Collective Goals in an Open Future Learning Space," Journal of Learning Spaces 9, no. 1 (2020): 19–30. Jump back to footnote 6 in the text.

- Colin Loughlin, Steven Warburton, Susan Crane, and Wendy Sammels, "Towards Active Learning Spaces and the Flipped Classroom Model," in Proceedings of the 14th European Conference on e-Learning, ed. Amanda Jeffries and Marija Cubric (Hatfield, UK: ACPIL, 2015), 29–30. Jump back to footnote 7 in the text.

- Sawers et al., "What Drives Student Engagement," 26–38. Jump back to footnote 8 in the text.

- Loughlin, Warburton, Crane, and Sammels, "Towards Active Learning Spaces," 29–30. Jump back to footnote 9 in the text.

- Rebecca Donkin and Mary Kynn, "Does the Learning Space Matter? An Evaluation of Active Learning in a Purpose-Built Technology-Rich Collaboration Studio," Australasian Journal of Educational Technology 37, no. 1 (2021): 133–146. Jump back to footnote 10 in the text.

- Sawers et al., "What Drives Student Engagement," 26–38. Jump back to footnote 11 in the text.

- Liat Enyal and Einat Gil, "Design Patterns for Teaching in Academic Settings in Future Learning Spaces," British Journal of Educational Technology 51 no. 4, (March 2020): 1061–1077. Jump back to footnote 12 in the text.

- Donkin and Kynn, "Does the Learning Space Matter?" 133–146. Jump back to footnote 13 in the text.

- Alexander Freeman, Samantha Adams Becker, and Michelle Cummins, NMC/CoSN Horizon Report: 2017 K-12 Edition, research report, (Austin, TX: The New Media Consortium, August 2017) Jump back to footnote 14 in the text.

- Enyal and Gil, "Design Patterns for Teaching," 1061–1077. Jump back to footnote 15 in the text.

- Ibid. Jump back to footnote 16 in the text.

- Smardon, Charteris, and Nelson, "Principals' and Teachers' Perceptions," 149–171. Jump back to footnote 17 in the text.

- Rook et al. "Forming and Sustaining a Learning Community," 19–30; Yotam Hod, "Future Learning Spaces in Schools: Concepts and Designs from the Learning Sciences," Journal of Formative Design in Learning 1 no. 2 (2017): 99‐109. Jump back to footnote 18 in the text.

- Ibid. Jump back to footnote 19 in the text.

- Marie Leijon, and Björn Lundgren, "Expanding Learning Spaces in Higher Education – Understanding a Hyflex Model," in Proceedings of the European Distance and E-Learning Network 2015 Annual Conference, ed. António Moreira Teixeira, András Szűcs and Ildikó Mázár (Barcelona, Spain: European Distance and E-Learning Network, 2015), 964–970. Jump back to footnote 20 in the text.

- Sawers et al., "What Drives Student Engagement," 26–38. Jump back to footnote 21 in the text.

- Donkin and Kynn, "Does the Learning Space Matter?" 133–146. Jump back to footnote 22 in the text.

- Irit Sasson, Noam Malkinson, and Tutia Oria, "A Constructivist Redesigning of the Learning Space: The Development of a Sense of Class Cohesion," Learning Environments Research (March 2021). Jump back to footnote 23 in the text.

- Donkin and Kynn, "Does the Learning Space Matter?" 133–146. Jump back to footnote 24 in the text.

- Smardon, Charteris, and Nelson, "Principals' and Teachers' Perceptions," 149–171. Jump back to footnote 25 in the text.

- Sasson, Malkinson, and Oria, "A Constructivist Redesigning of the Learning Space," (March 2021). Jump back to footnote 26 in the text.

- Donkin and Kynn, "Does the Learning Space Matter?" 133–146. Jump back to footnote 27 in the text.

- Ibid. Jump back to footnote 28 in the text.

- "Pathways Curriculum," Ohio University Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine (website), accessed October 14, 2021. Jump back to footnote 29 in the text.

- Sawers et al., "What Drives Student Engagement," 26–38. Jump back to footnote 30 in the text.

- Ibid. Jump back to footnote 31 in the text.

- Donkin and Kynn, "Does the Learning Space Matter?" 133–146. Jump back to footnote 32 in the text.

- Loughlin, Warburton, Crane, and Sammels, "Towards Active Learning Spaces," 29–30. Jump back to footnote 33 in the text.

- Ibid. Jump back to footnote 34 in the text.

- Rajeev S. Muthyala and Wei, "Does Space Matter? Impact of Classroom Space on Student Learning in an Organic-First Curriculum," Journal of Chemical Education 90, no. 1 (2013): 45-50. Jump back to footnote 35 in the text.

- Sawers et al., "What Drives Student Engagement," 26–38. Jump back to footnote 36 in the text.

- Donkin and Kynn, "Does the Learning Space Matter?" 133–146. Jump back to footnote 37 in the text.

- Adedokun et al., "Student Perceptions of a 21st Century Learning Space," 1–13. Jump back to footnote 38 in the text.

- Ibid. Jump back to footnote 39 in the text.

- Loughlin, Warburton, Crane, and Sammels, "Towards Active Learning Spaces," 29–30. Jump back to footnote 40 in the text.

Jodie Penrod is Senior Director, Technology, for the Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine at Ohio University.

© 2021 Jodie Penrod. The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0 International License.