The choices that institutional leaders make regarding outsourcing IT processes to third-party suppliers hang on techno-social issues that hold existential ramifications for higher education.

Without a standard methodology for differentiating processes, most executives find it tough to distinguish among core processes . . .1

Digital transformation (Dx) is reshaping the higher education landscape. Defined as the journey an institution takes from analog, legacy practices to digital, modern processes, Dx has impacted course lectures, transformed organizational models, and affected strategic planning.2 It is also affecting the choices higher education leaders are making in regard to outsourcing IT processes to third-party suppliers. Taken in aggregate, these choices represent far more than just technology advancements or procurement decisions. They underscore techno-social issues that hold existential ramifications for higher education.

Thoughts on the impacts of Dx now permeate higher education. In the past year, EDUCAUSE has published more than one hundred items on Dx and highlighted it in numerous sessions at its annual conference. Along with the useful affordances of Dx, homegrown IT solutions supporting higher education's value chains are increasingly being disrupted and subdivided into discrete, fee-based, external support services. As applications are modernized, campus services are being reevaluated to align with a digitally transformed, cloud-based marketplace—from admitting students and providing financial aid to teaching, research, conferring degrees, and beyond.

While these new Dx-enabled capabilities enhance key experiences for campus constituents, the feature propositions, technology footprints, and price segmentations increasingly fractionalize and collide with well-established campus decision-making practices.3 Each external, value-added microservice becomes a source of excessive optionality, spawning competing and conflicting viewpoints among campus leaders on the proper course of action, perhaps without sufficient regard to the economic impacts of sprawling costs or the broader, long-term existential implications.

In keeping with George Santayana's statement that real progress is rooted in the memory and retention of prior experiences,4 the history lessons advanced by Ravi Aron and Jitendra Singh in their Harvard Business Review article, "Getting Offshoring Right" may resonate as touchstones for digital transformation. Decades ago, offshoring business processes became a widely adopted practice that promised lower costs by leveraging overseas labor pools. Companies hoped that by allocating local resources more efficiently, they could obtain higher quality results. In many cases, the higher quality was not realized and, once companies contracted with external suppliers, overall costs began to rise. Some of those offshored business processes proved successful, but many services were ultimately reshored. Such experiences, in turn, forced many leaders to scrutinize their business processes to determine which ones were best suited to offshoring.5

A key insight shared by Aron and Singh is that most companies don't spend enough time up front evaluating which processes to offshore, nor do they use reliable approaches to make those determinations. In practice, the lowest cost often wins the day, and when offshoring decisions are primarily based on a simplistic cost/benefit duality, leaders may underestimate operational and structural risks.6 The article argues that executives must instead align technological decisions with the core needs of their organization.

Aron and Singh's lessons about offshoring provide a useful analogy for outsourcing campus IT services to commodity Dx cloud providers.7 While past governing boards made decisions to offshore enterprise systems or entire parts of an organization, the decision-making process for the acquisition of modern commodity IT services can be much more granular. The question, "What technology is provided by my campus?" has shifted to more proactive, client-driven questions like these: "My department is using a free, new technology. How can I get the university to purchase a subscription? How can it be integrated so my students can use it?"

The increased availability of commodity services—services that are easily obtained from third parties at low costs—and the expanded agency with which departments, faculty, and staff can independently initiate and deploy solutions, present new challenges. When services can be procured independently, campus concerns about data use policies, accessibility, privacy, technical integrations, budget requirements, etc., can be completely overlooked. Increasingly, IT departments may have little insight into all the tools that faculty or departments are actually using. Individual decision-making to purchase such-and-such solution can be brought about by direct-to-faculty marketing emails, targeted webinars, and social media outreach. In turn, these promotional activities result in micro-purchases that effectively unbundle an institution's traditional purchasing processes and service value chains into further discrete units of profitability for the organization's partners.

The benefits and efficiencies of Dx bring additional, often hidden risks with each unsanctioned click of an "I Agree!" terms and conditions button. This can result in process change for internal campus business partners, redesign of instructional delivery functions, and the sequestration of data into proprietary off-premise silos. Consider the difference between a single, near-effortless digital transaction and the far-reaching consequences of those transactions taken in aggregate.

Another unsurprising outcome of the march forward of Dx is that higher education simply cannot afford all of the tempting value that is now being offered. For example, although many suppliers promote "student success" services, this term can mean very different things to different institutions. While new services obtained from an external supplier often bring excitement and the promise of enhanced functionality, institutions should consider whether its student success goals actually align with the supplier's product offering. If IT leaders are not working closely with stakeholders to define value, institutions may end up pursuing products that fail to meet the dynamic and complex needs of their campuses.

One remedy, and an important reminder from Aron and Singh, is to understand the core business. In addition to helping their institutions navigate the inevitable shift to cloud technologies, higher education leaders must develop effective value measurements to understand the impact Dx choices have on teaching, research, counseling, and other core endeavors. IT leaders, often guided by mission-critical needs, would be well advised to confirm that their understandings are in alignment with those of their colleagues in other units on campus, such as the academic senate or student affairs. It might not be surprising to discover that the phrase "mission critical" is perceived differently by different campus groups.

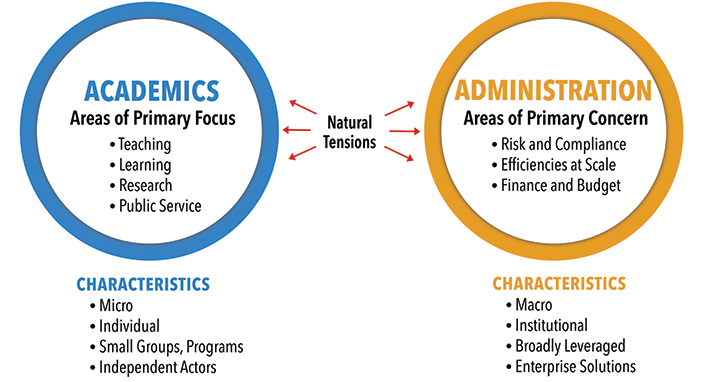

When faculty view the IT department(s) or IT leaders as supportive of their academic needs, there may be less impetus to seek out independent external solutions. But this is not as simple as it seems: As a sector, higher education—like health care and the creative arts—is defined by the inherent tension between humanistic values and commercial realities. The diagram below illustrates the tension between the academic realm, which struggles to preserve long-established principles around teaching, learning and research, and the administrative realm, which strives to situate academic values within the fast-charging, profit-driven world of Dx.

As Aron and Singh advise, leaders need to differentiate between the services that are appropriate to offshore and those that are best kept on-site. Today, those calculations have become nebulous for end users, support service departments, and enterprise IT. Through frictionless digital transactions, faculty end users, unencumbered by centralized purchasing authorities, can select products that are valuable for their immediate purposes. This is a momentous change for higher education and an existential conundrum: more than ever before, a campus' technology choices and its relationships with external suppliers influence its internal business functions, shape the roles of staff professionals, and may have impacts on the identity of an institution.

Higher education IT shops are moving out of local development and into commodity services procurement. Even higher education IT leaders who have led successful digital transformation efforts and feel that they are effectively coping with their new role as broker/dealer may hesitate at the velocity of change implied by Dx, knowing that pursuing each active opportunity and subscribing to microservice after microservice is not a sustainable model. The sheer volume of service modifications, coupled with the tremendous effort to optimally manage an evolving mix of on-premises and external subscription services, generates a significant amount of complexity and apprehension for all parties. Users are confronted with understanding new features, while policy and IT departments scramble to ensure those features align with campus governance needs. Suppliers may be good at facilitating rapid feature deployment and warranting consistent operations, but IT departments know that the campus ultimately retains the risk and the inexorable responsibility of supporting and delivering the intended value to its end users.

Locked in the crosshairs of free enterprise and unable to evade the surge of micro-purchases at the local level, the educational IT product value chains will continue to be fragmented, and costs will inevitably rise. Through the services they sell, suppliers are subtly conditioning universities to adopt their corporate values and practices. Absent an awareness of supplier values, universities may weigh competing options largely through the myopia of cost, putting themselves at risk of unwittingly adopting product design philosophies that can diminish institutional distinctiveness.

In response, campus process owners must continue to engage and collaborate with their IT departments. In addition to sharing normal request for proposal (RFP) information about needs, requirements, and technology roadmaps, purchasing decisions must be rooted in user-centered value discussions that reflect local interpretations of and contributions to the overall institutional mission. Process owners are often not asked to open up and describe how their business decisions are made. Yet, establishing standard practices in decision-making could pave the way for a new, campus-level modus operandi for IT governance.

Higher education institutions often engage in good-faith efforts to collaborate, be that within a campus, through university or regional consortiums, or across the sector. Even with a willingness to work collaboratively toward joint pricing agreements, and despite a storied commitment to share information, higher education cannot compete with the deftness of free enterprise to reinvent itself.

Given this difference, how can higher education operate within the market forces brought about by digital transformation? In the university setting, Aron and Singh's solution to develop standard methodologies and common understandings of what constitutes a core process may not be viable in light of the speed and hyper-optionality that pervade the technology market space. Continuing to operate within current governance structures and organizational systems would be glacially slow and only result in politically hard-fought, incremental improvements. Nonetheless, higher education should not passively consume the technology and economic changes brought about by our partner suppliers.

As portrayed here, digital transformation can introduce increased levels of uncertainty and chaos that disrupt the status quo: this is "fragilizing," and most acutely felt in organizations where IT service commodification has resulted in highly distributed accountability and increased sometimes hidden structural risks.8

Resigned to the ineluctable impacts of Dx, a novel solution would be to adopt an antifragile mindset and leverage impact investing. Higher education may be able to gain ground by promoting its values through the lens of its massive institutional investment power. Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) investing, also known as "impact investing," brings together "socially conscious investors [who use these criteria] to screen potential investments."9 In her book Real Impact, Morgan Simon describes impact investing as the practice of "selecting for-profit investments in light of a growing awareness of the social and environmental outcomes of such investments."10 Impact investing can accelerate change in ways that would not otherwise be possible via normal channels or individual discussions with suppliers.

As part of a long-term strategy, working through member organizations such as EDUCAUSE and the National Association of College and University Business Officers (NACUBO), campus leaders should have IT and financial departments identify companies that share their values and thereby lessen systemic risk. An ESG-type fund could be created to identify, nurture, and reward suppliers whose business philosophies are in line with the principles and practices that are of critical importance to higher education, such as IT security, accessibility, data privacy, and affordable education.

By leveraging impact investing, higher education can champion its values and shift the field of play from microtransactions to corporate boardrooms where venture capitalists can realize the strategic advantage of operating as responsible partners. If successful, higher education may be able to move suppliers from short-term thinking focused on profitability and market share to long-term relationships built on shared values and conscious capitalism.

Notes

- Ravi Aron and Jitendra V. Singh, "Getting Offshoring Right," Harvard Business Review, December 2005. ↩

- Jim Phillips, Jim Williamson, and Nic Brummel, "Seizing the Moment: Social Dynamics and the Remote Student Experience," EDUCAUSE Review, June 17, 2019; Jim Phillips and Jim Williamson, "Dx and Evolving Organizational Models," EDUCAUSE Review, October 14, 2019; Jim Phillips and Jim Williamson, "Strategic Planning and the 'Perpetual Whitewater' of Dx," EDUCAUSE Review, August 12, 2019. ↩

- Jim Phillips and Jim Williamson, "Strategic Planning and the 'Perpetual Whitewater' of Dx," EDUCAUSE Review, August 12, 2019. ↩

- George Santayana, The Life of Reason: The Phases of Human Progress, vol. 1, Reason in Common Sense (New York: Dover, 1905–1906). ↩

- Aron and Singh, "Getting Offshore Right." ↩

- "Operational" is the risk that a service is not efficient or successful; "structural" risks arise when providers fail to live up to their initial obligations (Aron and Singh). ↩

- We use "commodity" throughout as shorthand for external cloud solutions that offer identical services to all customers. Aspects of these services can include data comingling and product development and feature release cycles over which customers may not have direct input or control. ↩

- The philosopher/educator/economist and gadfly Nassim Nicholas Taleb uses the term "antifragile" to describe organizations, systems, and other dynamic entities that improve when they are under duress. Nassim Nicholas Taleb, Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder (New York: Random House, 2012). ↩

- James Chen and Gordon Scott, "Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Criteria," Investopedia (website), February 25, 2020. ↩

- Morgan Simon, Real Impact: The New Economics of Social Change (New York: Bold Type Books, 2017), p. 32. ↩

Jim Phillips is Director of Campus Engagement, Information Technology Services, at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Jim Williamson is Director of Educational Technology Systems and Administration at the University of California, Los Angeles.

© 2020 Jim Phillips and Jim Williamson. The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 International License.