Smart leaders know that the organizational changes brought about by digital transformation are as much about people, staffing, and training as they are about technology. Foregrounding that knowledge as part of organizational transformation may also provide a positive way to address long-standing problems.

Other Articles in the "Dx in Practice" Series:

In High Velocity ITSM, Randy Steinberg describes recent changes in technology: the new playbook includes concepts like "lean," "agile," and "DevOps."1 While these terms may be yesterday's news for many involved in the commercial sector, they may be novel to those in higher education.

It wasn't so long ago that IT service management (ITSM) began to dominate thinking in higher education IT organizations. ITSM represents a significant shift from traditional systems management approaches that focused on formalized, top-down decision-making, foundational infrastructure needs, and linear, waterfall development methodologies. With its reliance on well-defined processes, such as practical service definitions, design review, and change advisory boards, ITSM focuses on delivering customer value.

As the technology sector matures, cloud functionality—including server virtualization, scalable storage, and unbundled subscription services—is increasingly popular, largely due to low costs, increased capabilities, and flexible purchase options that may or may not involve traditional campus procurement processes. Meanwhile, driven by user enthusiasm and amplified by rapid product obsolescence (cool today, meh tomorrow), adoption life cycles are becoming more and more compressed. All this means that higher education IT organizations find themselves operating in a very different theater.

The dynamic nature of digital transformation (Dx), which we define here as a journey from analog, legacy models to new digital processes, reshapes traditional IT structures and spurs change. But what does Dx mean for organizations and individuals working in higher education?

To answer this, one might look to the private sector—more specifically to Silicon Valley start-ups—and attempt to replicate organizational structures found there. Dx has prompted some higher education IT groups to adopt a start-up mentality, including lean thinking, rapid prototyping, agile teams, and accelerated service delivery. Rooted in the principle of local decision-making and customer feedback, the lean organizational model focuses on continuous improvement, adaptive processes, and cross-functional teams. Risk and users' expectations—not technology—drive IT change.

For some individuals in the tech sector, a Dx organizational transformation is a welcome relief and represents a new and viable pathway to sustaining relevance in their careers. Others, who feel as if their careers are in jeopardy, may see digital transformation as a perilous tilt toward corporatization, a threat to campus culture, and an erosion of the core values of higher education. In the blog post "The Automated University," Jonathan Rees, a professor of history at the University of Colorado, Pueblo, speaks to the reach of technology in the classroom: "The most dangerous aspect of introducing new technology into college classes of all kinds is that it might convince both edtech companies and many college administrations that they know how to teach better (which often just means 'more efficiently') than we do. When the decision to employ education technology is made exclusively by management, a structural imperative tends to move that technology towards its most evil iteration."2

Let's unpack Rees's statement about technology's "most evil iteration." Well-intended decision-making could result in automatized, templatized, lowest-common-denominator, anti-intellectual content delivery. Unrestrained data collection and surveillance could erode academic freedom, hiring decisions, and other essential foundations and values of higher education. But Rees is not a Luddite or scare-monger: his point is that educators must participate in discussions about technological change.

Encouraging thoughtful dialogue among college and university constituent groups is just one of the ways that the University of California Santa Cruz (UC Santa Cruz) hopes to temper the sweeping current of Dx and avoid the negative consequences Reese foresees.

Organizational Structures at UC Santa Cruz

Over a decade ago, the Information Technology Services (ITS) division at UC Santa Cruz had a structure that was fairly typical in higher education. The ITS division was organized around a set of central enterprise services, with groups of decentralized support staff embedded in the academic and administrative divisions.

At that time, the reallocation of distributed staff into a central ITS division resulted in efficiency gains, which helped to stave off service declines during a slew of successive California state budget cuts.

The campus has slowly emerged from the darkest days of the 2008–2011 budget downturn. Faculty lines and student enrollments have increased, and new campus construction projects have begun. In some cases, this growth occurred without commensurate IT investment. Technical debt ensued. The ITS division struggled to meet the needs of the campus and was sometimes put in the uncomfortable position of making tactical tradeoffs based solely on exigent needs.

In the summer of 2019, UC Santa Cruz's ITS division embarked on a major reorganization to promote lean thinking, strengthen customer focus, and develop a governance model where the consumers of the technology become participants in institutional decisions.

Now in the early planning stages, the organizational changes at UC Santa Cruz are designed to address a number of challenges that may sound familiar: Customer needs were sometimes delayed due to technology limitations or resource constraints. Some services were "one-deep" or siloed within a small group of technical support staff. It was difficult to implement division-wide technical standards. Performance metrics and key performance indicators (KPIs) were not always tracked, and data was not always used to provide leadership with actionable information on the technologies and services deployed.

Led by UC Santa Cruz's Vice Chancellor of Information Technology Van Williams, this transformation centers on developing a product mindset that aligns more closely with customer requests, improves the user experience, builds technical skill depth, and adapts more quickly to the dynamic needs of the campus. Underpinning this move to a product mindset is a deep commitment to staff conveyed through the following:

- Professional development to help individual staff members move toward their career goals

- Technical training to equip staff with the hard and soft skills needed to succeed, including agile methodologies to increase velocity and productivity

- An intent to foster joy at work so that all ITS staff members feel valued and able to contribute in meaningful ways by developing and taking advantage of their personal skills and strengths

The new focus on professional development and technical training enables unprecedented mobility and establishes the potential for staff to define their futures in the organization. The UC Santa Cruz ITS plan is intended to allow staff to pursue professional development in their areas of interest, job shadow to get a flavor for the real-world work experience of a new position, and even volunteer for a short-term rotation with a different technical group or product team.

Two tracks are currently contemplated for the rotation program: a technical track and a management track. The two-track approach establishes a farm system that is designed to produce tomorrow's technical leaders and managers from within. For the university, having employees who use their strengths and enjoy their work helps to increase productivity and positively impacts customer service. For staff, gaining a level of control over their career paths can help increase states of flow at work and lead to a greater sense of professional fulfillment. One of the most significant benefits the ITS division hopes to realize from this approach to professional development is a shift in organizational culture as it relates to career opportunities. This level of empowerment enables employees to envision organizational change as a healthy (not a threatening) aspect of the human work experience. By allowing staff members to explore and pursue different areas of professional interest, employees are better able to find what is referred to as ikigai, or where a person's passion and talents converge.3

In addition to helping staff better align their personal and career objectives, a parallel effort is under way to introduce a new organizational mindset—built on the principles of product management and lean practices—across the ITS division and the entire campus. This product-driven organization will move through work faster and automate business processes wherever possible, always adapting to customer needs. With a strong focus on ITSM and guided by the SAFe Lean-Agile principles, the ITS division will expand how it uses data to measure progress. One key role in the new organizational model will be the product manager, who will work closely with stakeholders to assess their needs, freeing up technical teams to focus on outcomes.

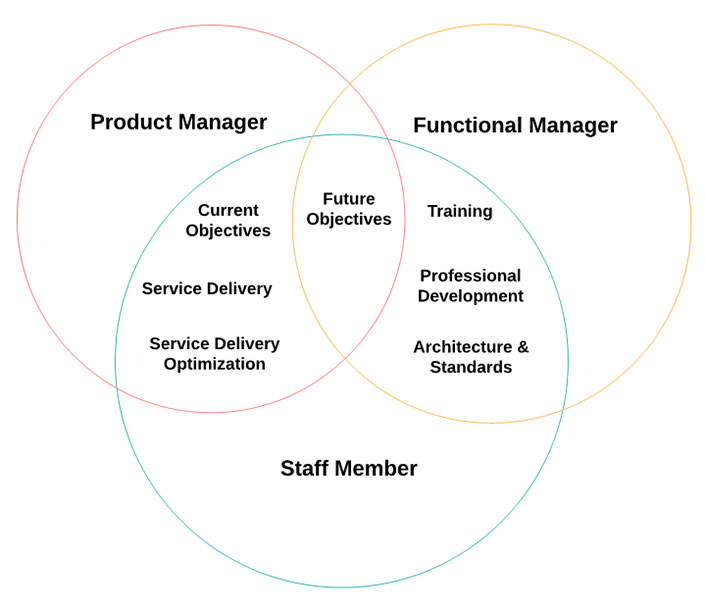

Each individual staff member will have two affiliations: The functional team, which defines the approach to work, and the product team, which is responsible for getting the work done.

Thus, each staff member will have dual reporting lines: the first to a functional manager, who oversees standards, policies, training, and professional development; and the second to a product manager, who oversees the staff member's work on the product team to ensure objectives are met, services are delivered, and projects are completed (see figure 1). The product teams will be cross-functional and empowered to resolve issues at the team level.

The vision of the transformation—to combine product management and a customer-centric focus with a commitment to staff training and professional development—is gaining momentum on the campus. Williams described how the effort transcends the ITS division:

We are not only transforming ITS: we are attempting to transform the campus. This change goes beyond digital transformation. It is about becoming the heart and soul of a campus strategic and cultural transformation that is built on being user driven, customer focused and operationally excellent. The goal of this transformation is to rethink and redefine what a higher ed organization can do when technology becomes a true amplifier of the academic mission.4

And as the journey continues, it is reassuring to see similar efforts across the UC system and among other institutions of higher education. There is, of course, a recognition that UC Santa Cruz may not get this 100 percent correct and, borrowing from agile terminology, will have to "inspect and adapt."

In the coming months, governance groups and campus leaders will engage in cross-domain planning and collaborative discussions of prioritization. UC Santa Cruz is changing because IT has changed. Technology has matured to a point where we are able to embrace a more customer-centric focus.

Impact on People: Developing New Skills for Higher Ed IT Staff

Lean thinking and product management approaches are clearly driving digital transformation and reshaping organizational structures in the tech sector. But what are the effects on staff?

The answer lies with each individual's appetite for personal development, their willingness to take advantage of support opportunities, and their ability to reinvent themselves. Consider cloud computing as one example of an impactful digital transformation. In the EdTech magazine article, "To Optimize Cloud Deployments, Close the Skills Gap," Wylie Wong describes the move to the cloud and its impacts on individual skill sets:

Colleges are embracing the cloud for its many benefits, including improved agility, security and manageability, and the potential for more cost-effective IT. But to reap those payoffs, IT staff must have the necessary skills to deploy and manage cloud services. They're also learning new ways to approach familiar tasks, resources, and procedures.5

As early adopters working through higher education cloud platform issues, universities like Emory, Notre Dame, and Harvard are among those who have shared their experiences in the EDUCAUSE Cloud Computing Community Group, often discussing the impact on staff to relay stories of success and concern. A 2016 Harvard presentation provides a nice summary and emphasizes the human factors involved in transitioning to the cloud:

- Migrating to the cloud is just as much of a people initiative as it is a technical project.

- Reduce the amount of time staff members spend performing two jobs.

- Do not turn all of the dials at once. It takes time to build a team, develop new skills, and learn new technologies.

- Everyone is accountable for cloud, not just the migration team.

- Communicate openly and often about successes and lessons learned.6

Harvard's approach aligns with UC Santa Cruz's emphasis on organizational change brought about through staff training and professional development. This is more than a feel-good, human-interest story. Case in point: cloud computing requires staff to learn new operational security controls. According to the 2019 Cloud Security Report from CyberSecurity Insiders, 40 percent of those surveyed identify "misconfiguration of the cloud platform/wrong setup" as their biggest cloud security threat, and 41 percent of respondents see staff training/expertise as the largest barrier to cloud-based security adoption.7

Smart leaders know that the organizational changes brought about by Dx are as much about people, staffing, and training as they are about technology. Foregrounding that knowledge as part of organizational transformation may also provide a positive way to address long-standing problems.

The Brain Drain

An ambitious reinvention of traditional IT structures such as UC Santa Cruz's transformation creates opportunities, but it must be done with care and commitment. Wholesale reliance on models imported from the tech sector may have lasting consequences for a higher education organization. Whereas the tech industry is characterized by aggressive business churn, colleges and universities have rich cultures and traditions, not to mention decades and even centuries of built up institutional knowledge.

One Silicon Valley feature higher education may not want to emulate is rapid staff turnover. Significant change, such as when the ranks of experienced staff are scuttled, can lead to customer dissatisfaction and organizational upheaval. Berkshire Consultancy summarizes the result as follows: "Behaviours and tacit understanding deliver hidden value to customers in a myriad ways, but we are not capturing this knowledge. This leaves organisations vulnerable to losing their capability when staff move positions, are promoted, or leave the business. It is becoming an increasingly complex issue to resolve."8

Organizational change can also be used to confront another long-standing problem in the tech workforce: the departure of women and minorities. The term "leavers" describes the phenomenon of people who have pursued a career in technology, reached positions of mid-level management, and, having grown tired of confronting obstacles such as unfairness and inequality, leave their jobs.9 Highly educated women are not merely quitting their jobs, they're opting out of the tech industry entirely.10

In a UCTech keynote address titled "Organizational Strategies for Interrupting Bias," UC Santa Barbara Professor Kyle Lewis describes strategies to create a healthy workforce and reduce departures. Lewis suggests ways organizations can improve, such as using language in job postings that appeals to a broader applicant pool and creating a welcoming climate and context for meeting candidates.11

The 2017 Kapor Center for Social Impact and Harris Poll survey, the first nationwide study on why people leave tech jobs, identified these four key takeaways:

- Unfairness drives turnover.

- Experiences differ dramatically across groups.

- Unfairness costs billions each year.

- Diversity and inclusion initiatives can improve culture and reduce turnover—if they are done right.12

PwC's annual survey for the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) provides possible remedies. The report notes that organizations making the most progress ensure that "diversity and inclusion (D&I) get the same direction, measurement, and accountability that would be applied to any other strategic priority." They point to "five key foundations for effective change:"

- Align diversity with your business strategy.

- Drive accountability from the top.

- Set realistic objectives and a plan to achieve them.

- Use data: what gets measured gets done.

- Be honest: tell it as it is.13

As technology transforms IT organizations, let's take the opportunity to amplify higher education's commitment to diversity. We can create new roles for a wide breadth of workers, use training effectively, and then rely on those newly trained staff to handle the complex digital modalities now appearing on our campuses, such as internet of things (IoT) and cross reality (XR) technologies.

Conclusion

Dx is changing the way people interact with work operationally, technically, and, as discussed here, organizationally.

In the context of organizational transformation, there is something timeless that becomes discernible whenever change takes hold: a natural reflex of our psyche. Our resilience gets tested. If the change becomes protracted, our ability to tolerate ambiguity begins to diminish and gnaw at our rational selves. In some cases, our inclination for self-preservation and aversion to loss can turn to anxiety or even panic. All of this can be misconstrued as resistance to change but is really quite predictable when seen through the kaleidoscope of human behavior.

Change, the duration of change, and the velocity of change can have lasting impacts on people and exact a significant emotional toll on an organization. Acknowledging the fatigue that people face as they go through massive organizational change can be an important step toward making the transformation successful.

Efforts to organize and reorganize, both individually and collectively, surface a critical link between present-day sensemaking and a deeply rooted human instinct born of some distant evolutionary past. No amount of leadership training can overcome the complexities of the human condition. The spaces between the names and positions on the organizational chart are what matter most: the human connections that result from our professional interactions and the friendships that people develop over a career of helping one another.

Notes

- Randy Steinberg, High Velocity ITSM, Bloomington: Trafford, 2016. ↩

- Jonathan Rees, "The Automated University," Remaking the University (blog), August 12, 2019. ↩

- Adela Schicker, "Ikigai – The Key to Longevity," Procrastination.com (blog), n.d. ↩

- Van Williams, email message to authors, August 12, 2019. ↩

- Wylie Wong, "To Optimize Cloud Deployments, Close the Skills Gap," EdTech, April 23, 2019. ↩

- Harvard University Information Technology, "CIO Strategic Initiative: Cloud" [https://huit.harvard.edu/files/huit/files/huit_connect_the_dots_120617.pptx], (PowerPoint presentation, June 13, 2016). ↩

- 2019 Cloud Security Report, research report, (Baltimore, MD: CyberSecurity Insiders, April 2019). ↩

- The Hidden 'Brain Drain' Problem, report, (Berkshire, UK: Berkshire Consultancy Ltd., January 2019). ↩

- "Women who leave science report both isolation and intimidation as barriers to their success. While 23 percent of [college] freshmen reported not having experienced these barriers, only three percent of [college] seniors did, suggesting that this reaction to women in science education is a lesson learned by female students over time (Jahren, 2016). In a survey of 191 female fellowship recipients, 12 percent indicated that they had been sexually harassed as a student or early professional (Jahren, 2016)." From "Diversity In High Tech," U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, May 2016. ↩

- Anna Beninger, High Potentials in Tech-Intensive Industries: The Gender Divide in Business Roles, research report, (New York: Catalyst, October 23, 2014). ↩

- Kyle Lewis, "Organizational Strategies for Interrupting Bias," Keynote speech given at UCTech 2019, Santa Barbara, CA, July 16, 2019. ↩

- The 2017 Tech Leavers Study, research report, (Oakland, CA: Kapor Center, April 2017). ↩

- Women in Work Index 2019, research report, (London, UK: PwC, March 2019). ↩

Jim Phillips is Director of Campus Engagement, Information Technology Services, at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Jim Williamson is Director of Educational Technology Systems and Administration at the University of California, Los Angeles.

© 2019 Jim Phillips and Jim Williamson. The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 International License.