Key Takeaways

-

Although active learning classrooms are designed to support innovative teaching and learning practices, classroom success requires sustained and intentional faculty development.

-

The University of Iowa and Indiana University each launched active learning classroom initiatives centered on faculty development.

-

These programs not only benefit individual instructors and their students, they are changing the pedagogy and culture at both universities in powerful and enduring ways.

-

The two cases offer many crucial findings about the design of both active learning spaces and faculty development programs to support success in and beyond individual courses and disciplines.

If you have recently visited a new or renovated college classroom, you may have noticed some changes, including technology enhancements, whiteboards mounted across the walls, and moveable tables and chairs. These are just a few features common within and across student-centered flexible learning environments,1 also known as active learning classrooms.2 Currently, more than 200 universities in the United States have these classrooms, and a growing number have formal campus-wide initiatives.

Although designed to support innovative teaching and learning practices, to succeed, active learning classrooms must be accompanied by sustained and intentional faculty development programs. Here, we address this crucial link by highlighting how two programs — the University of Iowa (Iowa) Transform, Interact, Learn, Engage (TILE) program3 and the Indiana University (Indiana) Mosaic Initiative4 — facilitate faculty development. Although both universities have spent the past several years creating new classrooms that support active learning, each institution recognized that simply adding these new classrooms was not enough. At the heart of the TILE and Mosaic programs lies an emphasis on professional development for faculty teaching in active learning classrooms, which differs fundamentally from teaching in more traditional classrooms.

Here, we explore this culture change at each university, starting with Iowa's TILE program. We first describe our early faculty development programs and their current formats, then offer case studies, and finally, explore our respective faculty development programs' wide-ranging, long-term impacts on teaching and learning.

The University of Iowa's TILE program

In 2009, the TILE program launched as a parallel effort aimed at faculty development, classroom renovation, and educational assessment. TILE rapidly moved Iowa's teaching focus and strategic planning to a more student-centered and engaged pedagogical approach. The resulting culture change in teaching at Iowa has generated an increasing demand for active learning classrooms and technologies. Most importantly, faculty members, administrators, and instructional staff across campus incorporate active learning into their teaching philosophies.

TILE Program Origins

Nearly a decade ago, funding for changing a few outdated classroom spaces provided the impetus to launch the TILE initiative at Iowa. A small group of executive leaders seeking ways to invest in high-tech spaces to support active learning recognized that investing in faculty development would be critical to leveraging the program's full potential.

To teach in the new TILE classrooms, faculty participate in faculty development, which ensures they have the time and support needed to explore strategies for designing and facilitating team-based, inquiry-guided courses that leverage the TILE spaces to enhance student learning. Funding for TILE research and assessment has also proven critical and supported rapid iteration for continuous improvement.

Early TILE Faculty Development Efforts

Iowa's early faculty development efforts focused on a few highly motivated faculty members who worked together in cohorts over time to redesign course activities. In 2010, the first TILE Faculty Fellows participated in a three-day institute led by North Carolina State University Professor of Physics Robert Beichner, who developed the SCALE-UP program. While most campuses at the time emphasized active learning spaces in STEM, Iowa encouraged instructors in all disciplines to use the spaces. Thus, from the beginning, TILE included humanities and social sciences faculty as well as STEM faculty.

The initial group of fellows expressed healthy skepticism, including Alison Bianchi, an associate professor of Sociology and a group processes researcher, who recalled her early views of TILE:

"My career has been about stamping out group hierarchies, and so when I was presented with the TILE experience, I feared that I would only perpetuate the very social inequalities I have vowed to wipe out. To my happy surprise, the originators of TILE classrooms had also thought carefully about these issues. For me, TILE classrooms are now a way to combat social disparities — the environment can be used to give every student a great chance to learn and participate."

The transformation of Bianchi's Research Methods course was remarkable. She knew that students had always dreaded the course because it was "boring, difficult, and required." Now, she said, it focuses on inquiry-guided, team-based learning:

"[The course] now allows the students to experience research methods rather than just take Research Methods. TILE provides the hands-on environment that has transformed my old class from passive lecture to very active group design work."

The enthusiasm of TILE's core group of faculty members spread quickly. Iowa built more TILE classrooms (a total of five opened between June 2010 and January 2012) and continued to provide pedagogically focused workshops to ensure that interested instructors could take full advantage of the rooms. As the program matured, funding to support stipends for TILE Fellows and institute presenters phased out. However, TILE had become part of Iowa's culture, and faculty members continued to invest time and energy in their ongoing development as they taught TILE courses and mentored new TILE colleagues.

Faculty Development Today

"TILE Faculty Support" offers a short overview of how TILE supports Iowa's teaching faculty today. Following that, we describe those components in more detail.

TILE Faculty Support

TILE faculty members today are supported by three primary components:

-

TILE Essentials, a two-part pedagogical workshop that partners new TILE instructors with veteran instructors to develop inquiry-guided, collaborative TILE courses in spaces designed to enhance active learning

-

Semester kickoff gatherings (facilitated by the Center for Teaching staff) where new and veteran TILE instructors share ideas

-

One-on-one consultations with teaching and learning specialists, student instructional technology assistants (SITA), and assessment staff members

All instructors who want to teach in a TILE classroom complete a two-part pedagogical workshop called TILE Essentials, which Iowa offers three times a year. The workshop is facilitated by staff members from the Office of Teaching, Learning & Technology (OTLT) Center for Teaching, who partner with veteran TILE instructors. Preparation assignments, available through ICON (Iowa's LMS), help familiarize participants with TILE's history and goals. In the workshop's first session, faculty engage in team-based, inquiry-guided activities that underscore the importance of aligning learning objectives with experiences and assessments in an active learning classroom. The facilitator models and explains strategies for teaching in TILE classrooms, including how to design and facilitate group work. Later in the session, a veteran TILE instructor demonstrates a team-based, inquiry-guided activity he or she uses in an existing course. During the demonstration, participants play the role of students and reflect on how specific aspects of the experience affect their learning.

As a capstone to the TILE Essentials experience, each participant designs a module that articulates a clear, measurable learning objective — detailing how they will assess that objective, how they will help students achieve it, and how they will leverage TILE classroom features. In the second TILE Essentials session, two members of the cohort volunteer to do a micro-teaching session, with each trying out a newly designed module. The other members play one of two roles: students, or observers who document and evaluate the classroom interactions. After each micro-teaching module, an experienced TILE instructor facilitates a discussion, guiding participants as they analyze each volunteer's approach and brainstorm how they might refine their own modules.

In addition to this workshop, Iowa also provides support through one-on-one consultations, which range from weekly meetings focused on redesigning a course to one-time meetings in which faculty practice a specific class session while being observed by a student instructional technology assistant, or SITA (as part of the Center for Teaching, SITAs are responsible for creatively leveraging teaching technologies).

Finally, TILE instructors keep in touch with the program through an online space in ICON. At the start of each semester, OTLT hosts a one-hour TILE Kickoff to encourage new and experienced TILE instructors to share ideas, ask questions, and reflect on TILE pedagogy.

Faculty Role in TILE

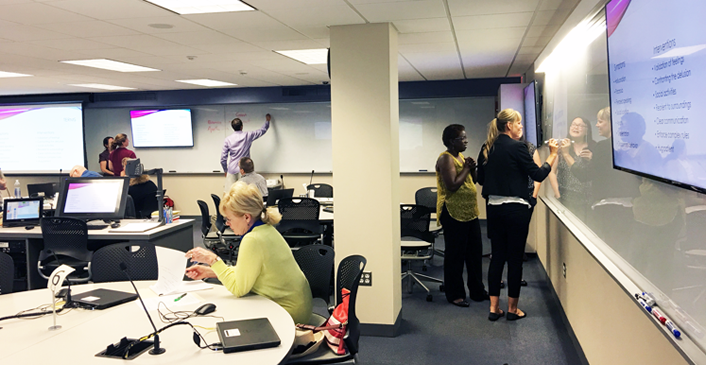

Both new and veteran TILE instructors help shape every aspect of TILE, from developing new TILE faculty to designing new spaces and piloting new tools. For example, in 2015, faculty feedback on a TILE survey led the university to create "TILE-lite" classrooms that use only the most fundamental TILE technologies — whiteboards and flexible seating.

Members of OTLT's Learning Spaces Team are also key TILE program partners; they attend the TILE Essentials workshops to better understand how faculty members use the rooms and brainstorm with TILE faculty about leveraging the rooms. In one case, faculty expressed concern about audio in spaces in which students had their backs to each other but seemed reluctant to use table-installed microphones. This led to the addition of new Catchbox microphones that students can pass — or even toss — around during discussions, promoting both participation and interaction.

At Iowa, TILE has become a widespread, grassroots program built on the enthusiasm and creativity of TILE faculty. A recent survey revealed that many faculty members include TILE training and participation in their CVs and professional teaching portfolios. They also attribute some of their professional outcomes — including research, publications, presentations, invited talks, and teaching awards — to their TILE involvement. As of fall 2017, 463 faculty, TAs, and instructional staff members have participated in faculty development to teach in TILE classrooms. As of May 2017, more than 80 departments have adopted TILE, and more than 31,000 students have enrolled in courses taught in Iowa's 10 TILE classrooms. Nancy Langguth, associate dean of Teacher Education and Student Services at Iowa's College of Education, underscores this point, remarking:

"Having the opportunity to teach University of Iowa teacher candidates in a technology-rich, collaborative setting is a gift, as the experience affords me the opportunity to model instructional practices that we hope the candidates will take into their work with K-12 students. The real gift, however, is that the TILE experience is much more than a technology-rich classroom; the experience includes professional development in how to best lead instruction in such a setting — a gift for which I am most grateful."

Related Iowa Initiatives

The philosophy in the TILE acronym — Transform, Interact, Learn, Engage — has now spread to and influenced other OTLT-led initiatives, including the Large Lecture Transformation (LLT) and the new Learning Design Collaboratory.

Launched a few years after the TILE program, the LLT clearly illustrates the impact of TILE faculty development. The LLT builds on TILE's success, providing significant pedagogical and technological support to faculty members seeking to transform existing large lecture courses into richer active learning environments.

Four faculty members from three large courses participated in the LLT, and all of them leveraged TILE spaces to transform their courses. Each auditorium-based course primarily used lecture to deliver subject matter to 160–230 students. Deep cognitive engagement occurs for students actively engaged with assigned tasks; in typical lecture-based courses, that engagement usually happens outside the classroom. However, as the following descriptions show, the faculty members leveraged TILE spaces to incorporate active learning components into their large-enrollment courses in various ways.

Adam Ward and Art Bettis, assistant and associate professors, respectively, of Earth and Environmental Sciences, redesigned the Introductory Environmental Science course by embedding one TILE session into each two-week topic module.5 Lecture sessions preceded each TILE session, which focused on in-depth discussion and various tasks involving application, analysis, or problem solving. The instructors deliberately ordered these sessions to provide an appropriate learning process sequence, with the lecture focused on subject matter knowledge and the TILE session focused on applying that knowledge in authentic contexts that require critical thinking and collaborations to arrive at plausible solutions.

In his Media History and Culture course, associate professor of Journalism and Mass Communication Frank Durham implemented active learning in TILE classrooms to transform the discussion sessions — led by teaching assistants (TAs) — from general question-and-answer periods to active learning sessions.6 Previously, the TAs had designed their own content for individual sections, producing inconsistent student learning across sections. During the LLT initiative, Durham developed a discussion curriculum integrating historic images, authentic documents, and various group activities. All learning materials were available from the university wiki platform. Students accessed these materials via laptops in a TILE classroom during weekly discussion sessions in which they collaboratively pursued answers to questions.

Finally, Mark Andersland, an associate professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering, turned his attention to Circuits, a course traditionally taught through straight lecture despite being a problem-solving course. Andersland decided to provide more in-class support for students' problem-solving efforts, which also allowed him to observe their processes and provide real-time, scaffolded learning opportunities. With OTLT support, Andersland redesigned the course to limit the lectures to 10 minutes, leaving sufficient time for students to engage in graded problem solving (through a digital platform) while he and his TAs responded to questions.

Mark Andersland's Circuits course

Andersland also encouraged students to work collaboratively with their peers. Even though students received individual grades, all problems were coded to parameterize each student's problems differently. Therefore, effective collaboration emphasized process rather than simply sharing answers. Assessment results indicate that students exposed to the TILE approach achieved higher learning outcomes on the same tests than students who learned the materials in a lecture-based course.

Building on TILE and LLT successes, the new Learning Design Collaboratory is a campus-wide initiative to support faculty in helping students achieve key learning goals. The Collaboratory provides instructional design support, faculty networking and professional development, and deep assessment of teaching and learning — as well as small fellowships to facilitate these endeavors. TILE pedagogies will play a key role in many Collaboratory-supported courses.

Cultural Shifts in Teaching and Learning

Because the TILE program focuses on faculty and engages them as key partners, it has influenced Iowa's culture around teaching and learning. Many TILE fellows serve as leaders and mentors in other campus initiatives, including the Learning Design Collaboratory and the Early Career Faculty Academy for new tenure-track assistant professors. One of the earliest TILE fellows, Cornelia Lang, associate professor of Physics and Astronomy, leads the General Education Curriculum Committee of Iowa's largest college. She also launched a series of active learning, team-taught, interdisciplinary "Big Ideas" courses. She explained her experience with TILE as follows:

"Teaching in TILE spaces at Iowa has transformed the way I interact with my students — instead of lecturing to a large room of curious students, I get the opportunity to work with them and to share the journey of learning together. Designing activities, discussions, and mini lectures to use in TILE classrooms has made me much more mindful of the way I teach — to consider the learning objectives for each class period and to build in time to interact directly with groups of students. This has been an incredibly rewarding experience!"

Early career faculty members increasingly embrace both the TILE classrooms and TILE as a pedagogy. Jean-François Charles, an assistant professor of Music, enrolled in TILE Essentials when he started teaching at Iowa in fall 2016. He noted that "The TILE classrooms would not be as useful without the associated faculty development programs." The TILE Essentials workshop was particularly important in his connecting with more experienced professors:

"TILE Essentials showed that designing a highly 'active learning' course requires a lot of work and planning, and I will certainly refer to what I learned in TILE Essentials when designing a learning activity for a new course."

Indiana University's Mosaic Initiative

Inspired by conversations with Iowa's staff about their successful TILE program, Indiana announced its Mosaic initiative in fall 2015. With more than 400 general-purpose classrooms on Indiana's two main campuses alone, it was crucial for the university to consider how it might transform a wide variety of classrooms to support active learning.

The name "Mosaic Active Learning Initiative" purposefully evokes a variety (mosaic) of different classroom designs rather than a single configuration (as with SCALE-UP). These designs range from spaces with moveable furniture, portable whiteboards, and wireless projection capabilities to spaces with more advanced technologies intended to promote active learning. Now encompassing multiple campuses, Indiana's Mosaic Initiative encourages faculty and staff to explore the intersections of space, technology, and pedagogy7 in a growing number of Mosaic classrooms.

At Indiana, the work of creating active learning spaces began with two projects. The first was The Collaboration Cafe, a classroom designed to facilitate active, collaborative learning in an environment that feels more like a coffeehouse than a classroom (see figure 5).8

The other early classroom renovation project was the Collaborative Learning Studio, which opened in fall 2013. Once a swimming pool, then a map library, the space is now a technology-rich collaborative classroom that seats 96 students (see figure 6). Located on Indiana's Bloomington campus, the Collaborative Learning Studio includes a 4 x 4 video wall on which an instructor can show 16 student table displays, providing a gallery view of their collaborative activities.9 These projects defined Indiana's early commitment to active learning spaces and its research into their effectiveness.

As these efforts built momentum, Indiana invited Jean Florman, director of Iowa's OTLT Center for Teaching, to spend a day exploring how best to support faculty teaching in the new active learning spaces. These conversations led to Indiana choosing the name "Mosaic" for its active learning initiative, to emphasize that every classroom would be different. At the outset, Indiana decided that customization and flexibility offered more value than a model based on a single design or range of designs (even highly effective ones). Thus, taken together, Indiana's classrooms represent a rich variety of learning spaces that meet widely varying instructional needs — much like the unique tiles that comprise a mosaic.

Expansion Across Indiana

In October 2015, Indiana announced Mosaic with a call for its Bloomington faculty to participate in the first cohort of Mosaic Fellows. In January 2016, the initiative publicly launched in Bloomington with a luncheon open to all Indiana faculty, staff, and students with Adam Finkelstein, professor at McGill University, as the keynote speaker. In September 2016, the initiative expanded to the Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis (IUPUI) campus, again with a luncheon welcoming its inaugural group of Mosaic Fellows. In April 2017, Mosaic arrived at Indiana's five regional campuses with a luncheon at Kokomo welcoming regional fellows.

The Mosaic initiative supports teaching in Mosaic classrooms in two key ways. First, the one-year fellows program gives a select group of faculty the opportunity to explore teaching in active learning classrooms and contribute to learning space development across Indiana (see "Targeted Support" for details). Second, for all Indiana faculty members who teach in active learning classrooms, Indiana offers

- Mosaic classroom workshops,

- open classroom sessions for faculty to observe actual courses in Mosaic classrooms,

- interactive tours of a variety of active learning classrooms to explore different designs and technologies, and

- one-on-one or group consultations (on request).

Indiana's goal with both faculty groups is to provide first-hand experience with different ways of engaging students in active learning spaces, and thus inspire instructors to try new classrooms and approaches while increasing their understanding of and comfort with each space's affordances.

Targeted Support: The Mosaic Faculty Fellows Program

The Mosaic Faculty Fellows program has four goals:

-

Prepare faculty members to teach in active learning classrooms by exploring a variety of instructional strategies and technologies

-

Build a community of faculty members who collaborate to advance their own teaching and to mentor other colleagues exploring and refining their pedagogical approaches

-

Promote evidence-based teaching by encouraging instructors to study how new spaces and instructional approaches impact student learning

-

Create faculty leaders who work together and with other stakeholders to guide the development of new learning spaces across the university

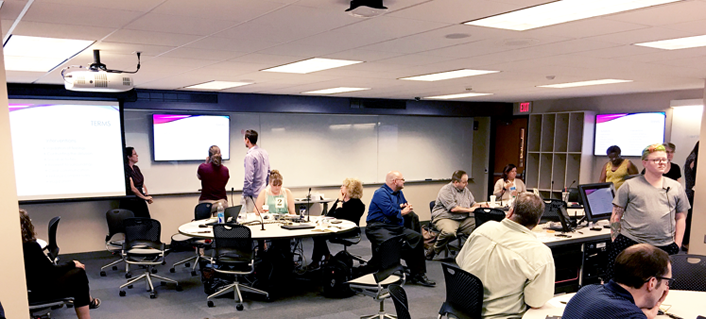

Three cohorts of approximately 10–12 fellows from Indiana's Bloomington, Indianapolis, and regional campuses are chosen each year. As of fall 2017, 63 faculty members from across all Indiana campuses have become Mosaic Faculty Fellows. Each cohort begins with the Mosaic Institute, a one-day, hands-on exploration of active and collaborative learning that introduces a range of approaches and the growing literature on active learning classrooms (see figure 7).

The fellows meet in various Mosaic classrooms and explore how to apply different active and collaborative learning through different affordances in each space. The fellows also assume the role of students to more clearly understand their experience when adjusting to various display screens, collaboration technologies, whiteboard surfaces, and classroom configurations. Throughout the day, the fellows individually reflect on both the student perspective and how their experiences playing the student role might influence their instruction and how they encourage classroom engagement in their own discipline and courses.

The Mosaic Institute provides a foundational experience for collaboration, as the fellows continue to meet once a month throughout the academic year. In the first semester, they prepare to teach in their assigned active learning classrooms for the following semester, planning their class sessions in an active learning classroom, brainstorming how to leverage the classrooms to achieve their intended pedagogical aims, and discussing how to communicate new expectations to students (see figure 8).

In his experience as a fellow, Joshua B. Tolbert, assistant professor of Education at IU East, especially appreciated the focus on exploration and engagement with other faculty:

"Direct experiences collaborating in an active learning classroom … not only equipped us to be more attuned to our students' perspectives, but also allowed the group of fellows to coalesce through shared experience."

Fellow Rob Elliott, a lecturer in Computer Information and Graphics Technology at IUPUI, expressed enthusiasm about working with colleagues in various disciplines: "The breadth of experiences within the cohort nudged each fellow out of his or her comfort zone so we could truly examine the group's efforts through a variety of perspectives." In the second semester, the fellows share new approaches they are implementing in their Mosaic classrooms and collectively work through obstacles they encounter.

Advancing Instructional Research

The Mosaic Faculty Fellows program is designed to

- support faculty in their teaching,

- advance research on teaching and learning practices in active learning spaces, and

- broaden that research to include a more diverse range of academic disciplines and classroom sizes.

At the start of their fellowship, faculty members read and discuss research on best practices for active learning spaces. As Crystal Shannon, assistant professor of Nursing at IU Northwest, noted, this focus is key to achieving practical results:

"The integration of evidence-based practice for classroom engagement has been central to the development of my teaching. The required review of literature provided an opportunity to reflect on best practices, success, and challenges by others on the active learning journey. I look at this as another tool for my teaching toolkit, and it helps me to stay current and relevant."

Mosaic Fellows each receive a $1,000 research stipend, which they can use for conference travel, research support, or other fellowship-related needs. To further encourage them to conduct and disseminate research on their own active learning classroom experiences, Mosaic hosts a one-day research-planning conference in the spring and offers ongoing, one-on-one research consultations for personalized support.

By highlighting innovative research methods in this growing field, Mosaic has broadened existing scholarship to areas such as political science, composition, interior design, and applied health science. According to Susan Siena, a lecturer in the School of Public and Environmental Affairs at IU Bloomington, this research focus is both challenging and immensely rewarding:

"As someone who is passionate about teaching, I am always interested in trying new things that will improve outcomes for my students. Research in my own classroom fit the bill — an opportunity to learn more about what works, what doesn't work, and to try something new. However … the learning curve for understanding the appropriate methodology for educational research was a steep one! The support of Mosaic consultants has been invaluable in making this possible."

Mosaic Case Studies

Our Mosaic Fellows capitalize on the initiative by fundamentally rethinking their approaches to teaching and learning. As Shawn Boyne, a law professor at IUPUI, put it: "The program caused me to reassess the wisdom of simply lecturing to students and to think more deeply [about] how to engage students at higher levels." For many, the program's impact also extends to their research and service; for some, the shifts in perspective are pervasive. Indeed, as the following case studies illustrate, the initiative can launch fellows onto new career paths.

Case Study: Brian Krohn. An associate professor of Tourism, Conventions, and Event Management at IUPUI, Krohn has always considered himself a progressive instructor. Prior to becoming a fellow, he experimented with technology, various content delivery formats, and flipped classroom elements, yet he was concerned that much of what he implemented lacked pedagogical strategy. Despite improvements in student attentiveness and comprehension, the strategies increased neither student engagement nor buy-in. After discussing his experiences with other Mosaic Fellows, Krohn reflected on his own pedagogy and realized he had not considered active learning's full implications. Specifically, he realized that while technology can enhance active learning, it can also create an unnecessary barrier to students. More importantly, Krohn became keenly aware that learning space design is more impactful than technology for supporting active learning strategies.

Rather than occasionally incorporating a few active learning approaches, Krohn now uses active learning techniques in nearly every class, with team-based learning activities designed around the active learning space's layout. For example, students are assigned to work within groups at a designated table over the course of the semester. Previously, groups would rotate, requiring the groups to renegotiate norms and actions. Now, students complete cross-group activities by temporarily switching group members, but they always start with the same core group. This fosters engagement and helps students develop strong social bonds. Reluctance and hesitance to engage with peers quickly gives way to an openness to engaging with each other, which encourages more dialogue and participation.

Transformation from Indiana lecture classroom to interactive, collaborative learning space

In Krohn's courses, teamwork and collaboration are the new norms, and student perspectives have changed as a result. Students now

- have a clearer understanding of what is expected of them;

- embrace peer-learning and peer-teaching as tools for success, rather than signs of weakness; and

- have a greater appreciation of the class content's relevance to their career and life situations.

Krohn's perspective has changed as well. He is committed to researching ways to improve student learning and retention through increased engagement, and he now serves on a campus-level learning spaces committee.

Case Study: Kalani Craig. A clinical assistant professor of History at IU Bloomington, Craig began her fellowship interested in exploring how digital methods could support learning in a fixed-seating lecture hall. She had previously designed a way for her students to combine digital mapping with a simulation of the bubonic plague's spread through cities with different population densities. The technological tools helped students put 14th century Black Death accounts into more accurate historical representations of medieval urban environments, which made the panic and fear much more real.

In the first year of Craig's study, some groups struggled with the fixed-seating lecture hall's awkward ergonomics and technological issues. However, in the study's second year, an active learning classroom made a big difference. The Collaborative Learning Studio featured 16 six-chair pods anchored by large computer screens. It changed not only the students' interaction with the history but also their perceptions of the technology. The tools became a natural part of the classroom environment, rather than a technological barrier that competed with historical content. As such, students could think deeply about the history via digital methods not previously possible through the traditional classroom structure.

Perhaps more importantly, being a Mosaic Fellow changed how Craig taught within traditional classroom spaces. For example, she investigated how students use whiteboards, poster paper, and digital mediums in history argumentation. She found that if students can erase or revise their work in the early stages of crafting an argument about history, they are more likely to commit to a thought; writing with a permanent marker felt "permanent," so the students' best ideas never made it to the large-format paper. This proved to be a vital piece of successfully managing student discussions in an active learning environment.

Craig has extended her Mosaic work through an administrative appointment to codirect Indiana's Institute for Digital Arts & Humanities, which provides pedagogical support for arts and humanities faculty who want to use digital methods in their classrooms. Although fully digital approaches require tech classrooms, Craig has shown that classroom redesigns can include simple details such as better whiteboards, an extra projector, and movable chairs. Basic shifts like these make it possible to design analog activities that teach digital methods. In describing her experiences to date, Craig likes to quote Winston Churchill: "We shape our buildings, and afterwards our buildings shape us."

Larger Impacts: Space Design

Many Mosaic Fellows echo what Krohn and Craig found: Regularly engaging students in active learning requires an environment that enables and encourages them to move, share, and learn from each other. Learning space design is thus the Mosaic Initiative's third pillar. All instructors discover a classroom's benefits and limitations while teaching in it — a fact that holds true for Mosaic classrooms as well. As such, Mosaic ensures that fellows have the opportunity to give our campus learning spaces team feedback on classroom designs.

The benefits go both ways: campus stakeholders benefit from direct contact with faculty, who in turn benefit from direct conversations about how space influences pedagogy. Elaine Monaghan, a journalism professor at IU Bloomington, described the larger impact: "I took great pleasure in being involved so directly in a core mission of this university … to make our classrooms better learning places for students."

Julie Johnston, Indiana's director of learning spaces, also meets with the fellows to discuss their feedback and the broader development of new active learning spaces across the university. Jenny Nelson, a fellow and Earth Science lecturer at IUPUI, described these feedback sessions as follows:

"[They were an] opportunity to step back from thinking specifically about the classroom we were teaching in, and think about active learning spaces as a whole. To think about Mosaic classrooms from a development standpoint opened my eyes to how much thought, planning, and design goes into every classroom innovation. What was most rewarding … [was] to know that our experiences and ideas would drive future renovations and development."

Johnston and her team experience similar benefits:

"Having the opportunity for extensive feedback from the Mosaic Fellows … has fostered a learning space design team that is purposeful and intentional about teaching and learning when creating new learning spaces."

At the end of their year-long program, the fellows collectively write a cohort report that captures specific recommendations for future Mosaic classroom designs, as well as possible incremental changes for traditional spaces that could help facilitate active learning. For example, in one IUPUI active learning space's original design, students in the middle of the room had no power outlets. Because the classroom relies on students' mobile devices to project to the interactive touchscreen wall, portable charging stations were placed throughout the room to ensure that students always have access to power (see figure 9).

Throughout the program, fellows are encouraged to reexamine their approaches to student engagement in Mosaic's active learning classrooms, as well as to meet a broader goal: to develop pedagogical flexibility. As Mosaic Fellows, faculty members are challenged to learn how to leverage any space they teach in to achieve their pedagogical goals. Meeting in various Mosaic classrooms helps fellows avoid focusing on only "their" classroom, while facilitating conversations about the different spaces broadens their sense of active learning possibilities.

In the final Mosaic meeting, fellows think more comprehensively about space and pedagogy by writing about how their lessons learned from Mosaic classrooms can be adapted to traditional spaces. The program and this reflection help the fellows develop a new skillset: the ability to leverage any space to support their pedagogical aims, rather than allowing a space to limit their vision of what students can achieve.

Reflections on TILE and Mosaic

For TILE and Mosaic, faculty development is neither an afterthought nor simply focused on getting faculty buy-in. Instead, faculty development builds on instructors' existing commitments to teaching and learning by encouraging them to actively contribute to the development of active learning approaches and spaces. As André Buchenot, assistant professor of English at IUPUI, stated:

"It is easy to think of the Mosaic initiative as a purely technical endeavor. After all, the most visible products are wonderfully appointed learning spaces. However, the initiative's most significant contributions to the university are its efforts to promote active, reflective teaching."

Further, IUPUI's Elliott speaks for many faculty in noting that the "fact that the Mosaic initiative was so visible and highly regarded within the university was very gratifying." Faculty at Iowa share this sentiment. Julie Jessop, associate professor of Chemical and Biochemical Engineering, explained:

"TILE has enabled me to transform my classroom into a lively, interactive, student-centered learning environment. It's difficult for me to give a traditional lecture anymore because I am better able to connect with my students, identify their weaknesses, and provide just-in-time support when I 'flip' instead."

Clar Baldus, clinical professor of Art Education at Iowa, agreed:

"TILE teaching is not a very efficient way to teach, but it is a most effective environment for messy, authentic learning. It's time we reconsider the factory assembly-line process of teaching where the professor is the 'sage on the stage' and the students disengage after the first ten minutes of lecture. TILE is a natural fit for my style of teaching, and I use the same approach even when teaching in non-TILE classrooms."

Impediments remain in changing teaching practice to implement active learning components, particularly in large lecture classrooms. Still, while many studies have noted student resistance to new and challenging ways of learning,10 students in TILE and Mosaic classrooms have come to fully appreciate a different way of learning as they adjusted to the new environments. In large part, this is due to both programs' emphasis on professional development and hands-on experiences for faculty teaching in these spaces, which made substantial transitions possible without overwhelming either the instructors or the students. Simply creating new classrooms is not enough: TILE and Mosaic do not just rely on exciting new designs and technologies — they leverage evidence-based teaching philosophies and cultural changes that bolster classroom engagement and student success.

Notes

- Robert J. Beichner, "History and Evolution of Active Learning Spaces," New Directions for Teaching and Learning, Vol. 2014, No. 137, 2014: 9–16.

- Paul Baepler, J.D. Walker, D. Christopher Brooks, Kem Saichaei, and Christina I. Petersen, A Guide to Teaching in the Active Learning Classroom: History, Research, and Practice, Stylus Publishing, 2016.

- Jean C. Florman, "TILE at Iowa: Adoption and Adaptation," New Directions for Teaching and Learning, Vol. 2014, No. 137, 2014: 77–84; Beth Ingram, Maggie Jesse, Steve Fleagle, Jean Florman, and Samuel Van Horne, "Transform, Interact, Learn, Engage (TILE): Creating Learning Spaces that Transform Undergraduate Education," in Cases on Higher Education Spaces: Innovation, Collaboration, and Technology, IGI Global, 2013: 165–185; Samuel Van Horne and Cecilia Murniati, "Faculty Adoption of Active Learning Classrooms," Journal of Computing in Higher Education, Vol. 28, No. 1, 2016: 72–93; and Samuel Van Horne, Cecilia Murniati, Jon D.H. Gaffney, and Maggie Jesse, "Promoting Active Learning in Technology-Infused TILE Classrooms at the University of Iowa," Journal of Learning Spaces, Vol. 1, No. 2, 2012.

- Tracey Birdwell, Tiffany A. Roman, Leslie Hammersmith, and Douglas Jerolimov, "Active Learning Classroom Observation Tool: A Practical Tool for Classroom Observation and Instructor Reflection in Active Learning Classrooms," The Journal on Centers for Teaching and Learning, Vol. 8, 2016: 28–50.

- Jae-Eun Russell, Samuel Van Horne, Adam S. Ward, Arthur Bettis, Maija Sipola, Mariana Colombo, and Mary K. Rocheford, "Large Lecture Transformation: Adopting Evidence-Based Practices to Increase Student Engagement and Performance in an Introductory Science Course,"Journal of Geoscience Education, Vol. 64, No. 1, 2016: 37–51.

- Frank Durham, Jae-Eun Russell, and Samuel Van Horne, "Assessing Student Engagement: Collaborative Curriculum for Large Lecture Discussion Sections," Journalism and Mass Communication Educator, July 2017.

- David Radcliffe, Hamilton Wilson, Derek Powell, and Belinda Tibbetts, Designing Next Generation Places of Learning: Collaboration at the Pedagogy-Space-Technology Nexus, The University of Queensland, 2008.

- Anastasia S. Morrone, Judith A. Ouimet, Greg Siering, and Ian T. Arthur, "Coffeehouse as Classroom: Examination of a New Style of Active Learning Environment," New Directions for Teaching and Learning, Vol. 2014, No. 137, 2014: 41–51.

- Dabae Lee, Anastasia S. Morrone, and Greg Siering, "From swimming pool to collaborative learning studio: Active learning in a large classroom space," Educational Technology and Research Development (in press); DOI: 10.1007/s11423-017-9550-1.

- Maggie Hutchings and Anne Quinney, "The Flipped Classroom, Disruptive Pedagogies, Enabling Technologies and Wicked Problems: Responding to 'the Bomb in the Basement,'" Electronic Journal of e-Learning, Vol. 13, No. 2, 2015: 105–118.

Anastasia (Stacy) Morrone is associate vice president for Learning Technologies at Indiana University.

Anna L. Bostwick Flaming is specialist in Teaching and Learning, Office of Teaching, Learning, & Technology, Center for Teaching, at the University of Iowa.

Tracey Birdwell is principal instructional technology consultant at Indiana University.

Jae-Eun Russell is associate director, Office of Teaching, Learning, & Technology, Research and Assessment, at the University of Iowa.

Tiffany Roman is graduate assistant for Learning Technologies at Indiana University.

Maggie Jesse is senior director, Office of Teaching, Learning, & Technology, at the University of Iowa.

© 2017 Anastasia S. Morrone, Anna L. Bostwick Flaming, Tracey Birdwell, Jae-Eun Russell, Tiffany Roman, and Maggie Jesse. The text of this EDUCAUSE Review article is licensed under the Creative Commons BY 4.0 license.