During my time as a higher education CIO, there have been conversations in the profession regarding what the college/university president should know about technology. In my mind, this is also a conversation about whether or not the CIO is responsible for providing IT knowledge to the president. As I’ve thought about this debate, I’ve considered how the CIO, as the IT communicator and translator — that is, the IT educator — can best support the president and other members of the institution management team (IMT).

In most cases, a higher education institution does not exist to produce technology. It produces graduates who go on, ideally, to improve their own lives and our society. The institution may also be engaged in research, and some of that research may be IT-focused, but research isn’t the only reason the institution exists. The president and the IMT are responsible for the leadership of the institution, but they cannot be knowledgeable about everything. If they were, why would they need the CIO? The president’s job is to focus on strategy, not tactics. Presidents should be concerned with the “what” — not the “how” — in technology. The “how” is the CIO’s job.

When I entered the CIO career field in the mid-1990s, some CIOs were feared by their colleagues, and even by their bosses, because the CIOs seemed to have some magic powers (or at least some secret information) that made them more powerful than the average employee. These CIOs could be arrogant and demeaning to the people they were supposed to serve. There have been a number of stereotypes and comedy sketches derived from this relationship between the IT leaders/departments and their customers. One of my favorites was Nick Burns, the computer guy. Nick was funny because he was over-the-top but also because the stereotype was very close to some realities. Nick would never explain the technology. He belittled the customer. However, real experiences like these resulted in a backlash that led many institutions to outsource the IT department or to bring in a leader from outside of the IT department.

During my almost two decades as a CIO in three industries and three higher education institutions, I’ve learned several things about the skills that are important for a CIO. In addition, I have conducted higher education CIO research over the past thirteen years. The Center for Higher Education CIO Studies (CHECS, http://www.checs.org) research is conducted annually through a survey sent to higher education CIOs and a second, similar survey sent to the IMT members. This longitudinal research has revealed how thousands of CIOs and their colleagues/supervisors on the IMT feel about the CIO’s skills and background. Beyond a doubt, communication is one of the most important skills for a CIO to have. And a critical aspect of communication skills is the ability to translate technology into everyday language. This translation helps the executive team and the president understand the possibilities and limitations of technology, without having to take an IT 101 class.

In my first CIO position, in a U.S. Air Force hospital, an encounter with a squadron commander (equivalent to a CEO) helped me grasp the reason CIOs are critical for an organization. The air force had produced a report on a hospital system that was having deployment problems. The report was sent to me, others, and the squadron commander. I found the report fascinating, and when I saw the squadron commander, I asked (with newbie enthusiasm): “Did you read this?” She looked at me, very seriously, and said: “No. That’s why you are here.” Before this encounter, I knew I was the IMT expert on technology, but this cemented my understanding of my role. The CIO helps the president and the IMT understand a very complex subject. Technology is important to most institutions, but again, it is not the reason the institution exists.

The CIOs from the CHECS 2016 CIO research agree. The CIOs and the IMT members are asked about the importance of various CIO roles and about the CIO’s effectiveness in those roles. The CIOs rated the IT Educator role (i.e., evangelist for computer use and understanding; educator of employees regarding IT innovations bringing value to the organization) as important (3.6 on a scale of 1 to 5) and rated the CIOs as effective (3.37 on a scale of 1 to 5). The IMT members agreed with the CIOs, rating the IT Educator role 3.76 for importance and rating the CIO 3.43 for effectiveness. Even though the IT Educator was the sixth most important role according to both groups, it is important. Only 1 percent of the CIO respondents and 8 percent of the IMT respondents indicated that the IT Educator was not the CIO’s job.

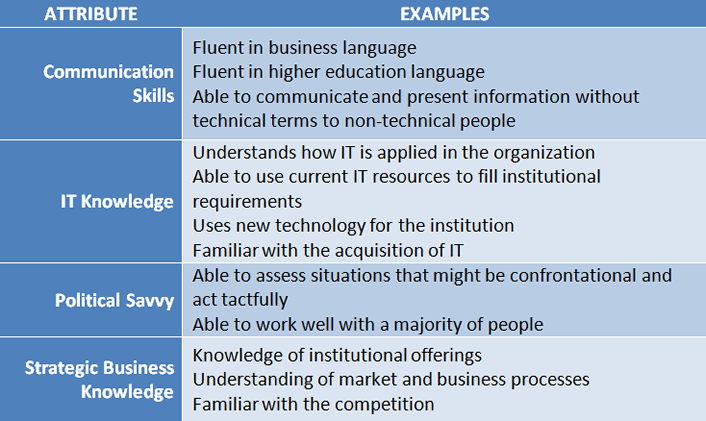

The CIOs and IMT members were also asked about the most important skills for a CIO to possess. According to the CIOs, this skill is communication. The IMT members selected communication as the second most important skill, following technical knowledge. Leadership was ranked second by the CIOs and third by the IMTs. Finally, the IMT respondents were asked about the CIO’s effectiveness in four areas: communication skills; IT knowledge; political savvy; and strategic business knowledge (see table 1). Their opinions about these four CIO attributes were collected through a series of questions. The IMT responses were aggregated to create an average for each attribute. Communication skills ranked 3.54 on the 1 to 5 scale.

Table 1. CIO Attributes and Examples

How can CIOs improve their communication skills? When I am giving a technology explanation to the president or to one of my IMT peers, I begin by going back to the basics. I determine who the audience is and what my purpose is for communicating. As IT professionals, we like to be precise. We don’t want to oversimplify at the expense of accuracy. However, we need to keep in mind that we are not trying to turn non-IT executives into CIOs. We also tend to use technospeak. This is not a helpful practice: it can be irritating and often gets in the way of good communication. I have found that the best way to communicate with the president and the IMT about complex technology projects is to translate the information into everyday language, use examples that are not technology-related, and bring humor to the conversation.

One example is open source software (OSS). Many non-IT executives think it is free. To install OSS, all we need to do is flip on a switch, and we will be off and running without all those big vendor license costs. My explanation of OSS for the non-IT executive is that OSS is “free” like puppies, not like beer. These few words generate a picture that is not threatening, may be funny, and gets the point across that care and feeding will have to be bought for our new puppy, OSS.

Another option is to use the “a picture is worth a thousand words” approach. I worked as a CIO for a college that had insufficient bandwidth from its wide area network (WAN) to the Internet. I had to approach the president for unbudgeted funding to improve this network. I asked one of the network leaders for a picture of the problem. The picture I received was a very accurate and detailed picture of the WAN, including IP addresses and lots of Visio symbols. I turned this into a picture of a large pipe from the WAN into a tiny pipe out to the Internet. The president immediately understood the problem and funded the improvements. The network leader, on the other hand, was very concerned that the picture was not literally accurate. But we have to keep the goal of communication in mind. The president did not want to rearchitect the network; he needed to understand the problem so that he could make a decision about an unbudgeted request.

CIOs are not the only ones who are expected to serve as the expert for their respective areas. The vice president for each area of an institution represents the expert for that area at an executive level. For example, when I need to get an understanding of how generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) impact cloud services, the CFO doesn’t tell me to look it up. He/she patiently gives me a lesson on capital-versus-expense costs and on how those costs are treated in accounting. Similarly, the marketing and admissions vice president doesn’t send me to Wikipedia when I am trying to grasp the enrollment “funnel”; he/she draws me a picture and explains the parts and potential leakage.

If the president can’t rely on a VP for expertise in an area, then why have the VP? CIOs are responsible for translating technology into everyday language and communicating the benefits and limitations of technology to the president and other members of the IMT. If we don’t do it, who will? Serving as the IT educator is our job as CIOs.

Wayne A. Brown ([email protected]) is Vice President for Information Technology and CIO at Excelsior College (Albany, NY). Brown is also the founder of the Center for Higher Education Chief Information Officer Studies (CHECS, http://www.checs.org/), a nonprofit organization focused on contributing to the education and development of higher education CIOs.

© 2016 Wayne A. Brown. The text of this article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

EDUCAUSE Review 51, no. 5 (September/October 2016)