Key Takeaways

- Moving faculty and staff to Gmail and Google Calendar required quickly training IT professionals across campus to support the new systems — which were not a priority among their other pressing concerns.

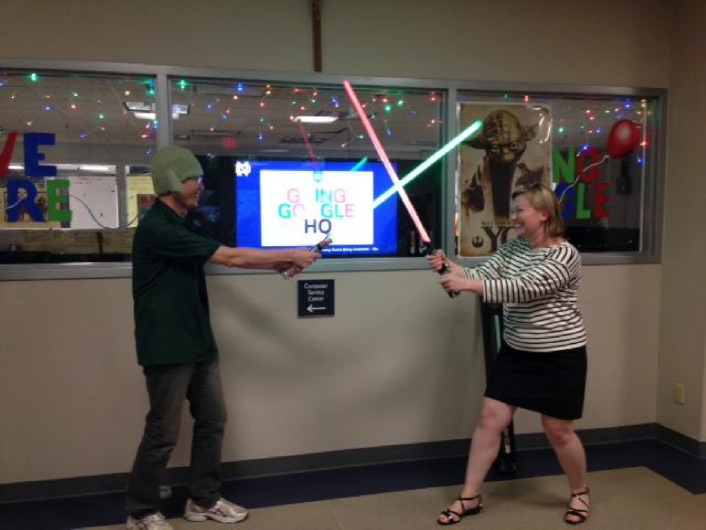

- Introducing gaming elements to the Google apps training via the Jedi Academy excited staff and faculty and attracted more participants than expected.

- As shown by the Jedi Academy's success, appropriate use of gaming elements can make otherwise mundane or avoided tasks, including support training, fun and rewarding.

Chas Grundy, Manager, Product Services, University of Notre Dame; and Matthew Belskie, Educational Technology Coordinator, University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee

Not too long ago, at a campus not too far away...

A packed auditorium peers down at an empty stage lit from above. Cantina music pops and bubbles through the room. Strange artifacts line the stage and adorn the podium. The music fades and a door opens. A young woman takes the stage. She wears a flowing white robe and tightly wound buns on either side of her head. She stands regally, microphone in hand, and addresses the audience. In just a few short moments, she will invite them to an exclusive order and the path to enlightenment: the Google Apps Jedi Academy.

Solving a Problem

When Notre Dame took faculty and staff to Gmail and Google Calendar in 2014, the project team had the challenge of quickly training 120 IT professionals across campus who had much more pressing concerns than learning how to support a new e-mail and calendaring system. Experience from past projects had shown that failing to engage distributed IT support staff could lead to poor end-user experiences, high demand for support, and dissatisfaction for the life of the product.

Based on concepts from the Google Apps Ninja Program [http://www.ninjaprogram.com/], the Going Google project team designed and launched the Google Apps Jedi Academy. The Jedi Academy focused on helping IT staff learn key tasks and features they would need to support.

The program tested campus IT staff on knowledge of the new Google platform. Each test moved participants up the ladder of Padawan, Jedi Knight, Jedi Master, or Yoda. Complete with Jedi cartoon characters, Jedi ceremonies, and prizes, the program spawned a new culture around the Going Google project. It proved so popular that many other staff asked to participate, including many who were not responsible for any end-user support. Ultimately, 237 people participated in the program; 207 of them achieved Yoda status.

When we surveyed participants, 92 percent indicated they learned new things, and some staff even made their own contributions to the program. One manager showed up with custom Yoda earrings, while several groups challenged other departments to competitions. Today, many Jedi Academy graduates display their Yoda buttons with pride. As one of the campus departments put it, "Involving all our faculty/staff in the fun helped set a lighter tone to the inevitable change."

The Case for Gamification

The earliest learning experiences we have as humans come through play, where we discover limits and gain joy from increasingly difficult achievements. Games, toys, and exploration help us develop physical skills, cognitive concepts, language skills, and social skills.1 When we enter formal educational settings, we suddenly abandon this natural approach and rely on lectures, readings, and other passive learning techniques. By the time we reach the workplace, businesses assume the best way to train an employee is using the formal educational model. And so the teaching methods that failed to stimulate and engage us as youth are once again foisted upon us as adults in our professional lives.

Recent approaches to education have begun to incorporate gaming in a strategic and deliberate way. Gamification has become rampant in marketing campaigns, for example. Similar efforts occur in offices around the world, introducing these elements to training, professional development, and even our daily tasks. Indeed, gamification has become a buzzword, and if you're like us, your eyes have already rolled at our use of the term (a necessary evil born of the Dark Side, we assure you).

As an older generation of employees ages out of the system and employees who grew up with games predominate in workplaces, it will become more necessary to adapt training to this audience. One estimate by Jane McGonigal put the worldwide total game time of all people in 2010 at about 3 billion hours per week.2 The median age of employees in higher education is about 42, and if you stop to consider your IT colleagues, you might guess a slightly lower age. One recent article even dubbed the generation that encompasses this group as the Oregon Trail generation, which many will recognize as one of the earliest educational games. For those in the Oregon Trail generation, game-based learning and gamified interactions made up a big part of our formative educational years and are in our blood.

Designing Your Game

Many gamification failures result from simply tacking points or badges onto an otherwise traditional program. Janaki Kumar and Mario Herger warned, "Do not just cover your broccoli with chocolate." In their book Gamification at Work they advise using a player-centered design approach:

- Know your player

- Identify the mission

- Understand human motivation

- Apply mechanics

- Manage, monitor, and measure3

Understand the Player

At Notre Dame, the target audience was IT staff; adopting a Star Wars theme made for a good fit with the training and was well-received. Such a theme might be a spectacular failure in a different context with a different audience, however. Think first about the participants and what they might enjoy, what they value, and what you expect of them.

Before beginning to design your gamified system, create rich personas based on your prospective audience. These personas will give you a lens to evaluate each of your decisions and assumptions going forward. Who is your typical participant? Are there multiple personas who can represent the different kinds of players?

Understand the Mission

Start at a high level (e.g., "Get better reporting on project hours") and dive deeper by creating a S.M.A.R.T. (specific, measurable, actionable, realistic, time-bound) goal. Be specific about what you intend and devise your mission accordingly. "Get 90 percent of staff to log their project hours within the next month" as the mission reframes the starting point appropriately. In our case we assume that having 90 percent of our staff acting in accordance with this goal to be realistic, but consider your baseline, your staff's ability, and mitigating environmental conditions. If currently only 10 percent of staff log hours, 90 percent might not be a realistic value. Or perhaps fewer than 90 percent of staff have access to the time reporting tool, or we know that a significant planned outage will occur during the one-month window.

Good games have clear objectives and leave players understanding how each action they take moves them closer to their goal. Likewise, training should have a clearly defined goal, and your gamified elements should align with that goal. Each badge or level or rank should represent clear progress.

Understand the Motivation

Research shows that different motivators vary in effectiveness depending on the task. Extrinsic motivators like rewards, recognition, or badges can be effective for simple tasks. However, they may be counterproductive or even harmful when applied to complex goals or problem-solving. With complexity, intrinsic motivators such as belonging, mastery, and relationships will prove more successful.4

The personas you developed at the outset will be key in this phase. As you design the training, walk each persona through the experience to test your design assumptions. For each one try to specifically understand why they might feel motivated to complete a step, and then continue to the next step.

Understand the Mechanics

Easily the most common topic when discussing gamification, mechanics are the elements that help make it a "game." Points, badges, and leaderboards are common mechanics for games. However, successful games often integrate elements such as stories (e.g., Star Wars theme) or constraints (a countdown timer or finite currency) to add richness.

At the heart of a gamified system lies the objective, not the mechanics. Your objective and audience should drive the mechanics you decide to implement. If you begin with the mechanics — "I want badges; can we use badges with some training?" to which your employees might respond, "Badges? We don't need no stinking badges" — then likely the gamification and the training will not align with the objective.

Manage, Monitor, and Measure

Fun and novel, gamification also needs to be effective. Plan your strategy up front for what constitutes success, how you will measure effectiveness, who will manage and support it, and how you will revise the program if the strategy proves ineffective. It's easier to add measures before you launch, so build those in from the beginning.

Because someone will feel ownership of this gamified training, its failure can feel like a tough blow. Making sure that you hew to the training objectives and organizational mission as you determine the assessment criteria, and creating that assessment prior to releasing your training into the wild, will help soften the blow of negative feedback and permit objective assessment of the training to improve it.

At the end of the Jedi Academy program, Notre Dame solicited feedback from participants. While most responded positively, some criticized the Star Wars theme, calling it unprofessional or distracting. However, most complimented the efforts and the program itself. One colleague submitted this praise: "Seriously, I can't really imagine what would have made this better. Amazing job."

Where It Can Go Wrong

As noted, it's relatively easy to introduce gaming elements and fall short of success. Recognizing some of the common pitfalls can help you create a better product at the outset and evaluate and improve your system when something does go wrong.

- Don't patronize users. Your colleagues are not children, so beware of treating them as children. The game should be fun for adults.

- Keep it relevant. Just because it's a game doesn't mean trainees will suddenly care about it. Good gamified interactions can't substitute for a bad training plan.

- Use appropriate game elements. It's too easy to get caught up in the idea of wanting to use a specific gamified interaction, such as badging, when badging doesn't make sense for the objective. Make sure the objective guides the gamified interactions you decide to use.

- Losing doesn't feel good. A game you can't win (or probably won't win) results in a lot of losers, which can create an entirely new problem. At the same time, be wary of removing all the challenge and complexity.

- Test early and often. It's critical to debug your gamified aspects. Testing also surfaces problems with reliability and validity, whether success with the gamified aspects translates to improved performance, and that performance holds true for all of your participants.

Common Game Mechanics

In 2010 Max Lieberman identified the four ways that games can be used to train or teach.4 The gamified interactions that we're presenting align with Lieberman's fourth method, game-like motivational systems, with game mechanics at the core. Simply put, game mechanics are the specific interaction elements between the player and the game and are the tools in your gamification toolbox. Knowing a wide range of game mechanics and how to use them appropriately keeps you from using a wrench to drive a nail (although you can drive a nail with a wrench, using a hammer yields better results).

Discovering game mechanics can be an enjoyable process, too. Simply play a game, any kind of game, and as you're playing think about the things the game does to make you enjoy it and want to keep playing. Each of these game mechanics is probably a good candidate to consider when you develop your own gamified systems. What follows are just a few common examples.

Leveling/Experience

Within games, experience is a non-arbitrary and quantifiable measure of progress toward some goal. You can use experience as a way to form a requirement for the certain number of times a task must be done before the user can progress, such as number of experience-yielding monsters to kill before leveling up in a role-playing game. The accumulation of experience usually results in gaining a level, a discrete milestone, and so it works as a mechanism to break a larger goal down into a certain number of much smaller goals.

Leveling can also occur sans experience point systems, with levels represented by completing a number of defined tasks or trials. A good non-game (but still gamified) example is how ranks work in the Boy Scouts. To achieve each rank requires earning a certain number of merit badges and displaying a certain set of proficiencies, followed by regular ceremonies to bestow new ranks (with accompanying badges). The most elaborate ceremony is held for those scouts who achieve the highest possible rank.

Badges/Achievements

Badges and achievements can work with or independently of many other systems. Going back to the Boy Scout example, badges serve as both a signifier of each gained level (rank) and as incremental progress toward each rank in the form of merit badges.

The core idea is that progress and mastery are rewarded with a token — the badge or achievement — and these things can be displayed as a source of pride or as proof that the gamer has accomplished a specific task. While digital badges are easy to implement, consider a real-world physical and tangible alternative inside of a physical and tangible workplace. The easier it is to display a badge, the better.

Rewards/Prizes

A reward can be any number of things. In games it can be earning a new, powerful item that looks really cool, or even getting access to game content such as concept artwork or soundtracks. Typically, more difficult challenges earn greater rewards. Many contemporary games feature multiple endings, with the "best" ending available only to those who beat the game on the hardest level or achieve certain difficult accomplishments through the course of the game.

Badges and rewards are differentiated by the badge having a more-or-less specified form and a clear relation to the work or task accomplished to earn it. Rewards can take any form and are generally something desirable.

To embed a gamified system within a gamified system, instead of awarding prizes directly, completing certain tasks can be rewarded with entries in a prize drawing. People completing or mastering more tasks get more entries, thus having a greater chance of winning a prize. The randomized drawing represents a different gamified element — a "game of chance."

Narrative/Mystery

In games, narrative is the story that connects everything — the game mechanic that affects the player's mood and impels continued game play. Narrative sets the stage and defines many of the social patterns of interaction.

In your own gamified system narrative can simply be the theme you decide to use, or even something as elaborate as a story to accompany progression through the training, with the story slowly revealed as the player progresses. Effective narrative should indicate to everyone, "We're in this same world together."

The Game Mechanics of Google Apps Jedi Academy

The design team for the Jedi Academy took advantage of the various game mechanics that best supported the training concept.

Prizes

The Jedi Academy offered basic extrinsic rewards — predictable reinforcement with prizes. Event attendees had opportunities to win prizes either through trivia contests or random drawings. Prizes consisted of inexpensive Star Wars toys and collectibles, even as small as Pez dispensers. These can still be found throughout our staff offices today.

Narrative

The team chose the Jedi theme partly because of its defined ranks and partly because of the compatibility with the audience. Regular e-mail newsletters, Jedi events, and the test website added to the narrative, featuring content that supported the theme. A special e-mail went out on Star Wars Day ("May the Fourth be with you") featuring jokes, comics, and videos. The program played out in our own world in a public way so that everyone could participate and achieve recognition.

Leaderboards and Leveling

Perhaps most importantly, the Jedi ranks corresponded to skill achievement. Some departments and colleges set expectations that their own teams would need to achieve Yoda level to effectively serve and support users. Other departments created challenges among themselves. The results were visible to all program participants through the leaderboard page on the testing website. This visibility generated competition and peer pressure, which led many to work harder to earn Yoda status. One colleague noted, "It was nice to have a fun goal to reach, not just tests to pass."

Badging

The team decided that physical badges conveyed an achievement even to those who did not participate in the program. A colleague with illustration talent developed cartoon versions of each character, and the team produced buttons of them — a literal use of badges, physical and easily displayed for others. As players earned their Jedi levels, they became eligible for a button depicting the corresponding Jedi character.

Other Gamified Examples

The Google Apps Jedi Academy represents just one entry in the wide world of gamified learning and training. A few other cool, gamified examples follow.

E-mail Game

Sometimes games can help make mundane tasks more tolerable or even fun. The E-mail Game is an overlay that turns your e-mail processing into a game, where you earn points for processing e-mails, lose points for leaving them in your inbox, and run a countdown timer while you respond. The goal is to improve your e-mail processing habits (process every message, respond efficiently, and defer action without leaving messages to clutter your inbox).

Vampire Hunter

Software giant SAP, like many other organizations, has pursued various sustainability efforts including conservation and energy reduction. One location, SAP Labs Palo Alto, developed a vampire hunter game to help identify "vampires" — products that waste energy. The team built a mobile app to help employees form vampire-hunting teams, take photos of vampires, and report their vampires back to headquarters. Players received feedback on how much energy they saved and could track their results on leaderboards. For SAP, not only does this reduce energy consumption and provide cost savings, but facilitates more employee interactions.

Live Ops

Call-center firm Live Ops increased engagement and decreased turnover by designing their work around a game. Call-center staff can earn points based on how quickly they resolve calls, how many calls they take, and the customer satisfaction ratings they receive. Participants outperformed non-players by 23 percent and left the firm half as often.

NextJump

Many organizations recognize the value (short and long term) of employee wellness and exercise, but struggle to get employees to commit to wellness programs. NextJump succeeded by establishing teams, points, leaderboards, and competitions to get employees to use the free office gym. Use skyrocketed from 5 percent to 80 percent of the workforce using the gym at least twice a week.

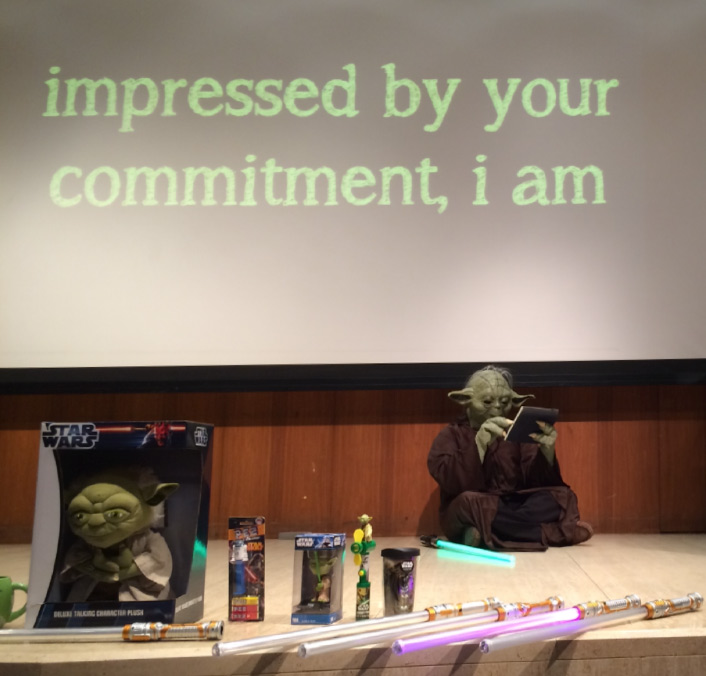

Closing Ceremony

Horns blasted a John Williams score and giant yellow letters crawled toward the top of the screen. An auditorium once again looked down upon a stage, but this time that stage featured a gentleman in a bespoke Jedi robe — one he had commissioned at his own expense. Beside him stood a small green figure with long ears, peering curiously at the crowd. This creature solemnly waved a green hand at the audience, commanding their attention. He held aloft a tablet upon which he had scrawled a series of messages. The screen above echoed his words: "Impressed by your commitment, I am. A successful transition, it will be. Important, your role is. Face of the technology, you will be. Project a sense of calm, you must. Have patience. Be positive. And succeed, you shall. My gratitude, you have." Unbeknownst to all but a few, this inspiring Yoda figure was played by none other than vice president and CIO Ronald Kraemer.

Acknowledgment

The Google Apps Jedi Academy program was presented at the 2015 EDUCAUSE Connect San Antonio conference. Slides are available online.

- University of California Davis, "Children Learn through Play," G.R.E.A.T., December 2006 [http://www.ucdmc.ucdavis.edu/CANCER/pedresource/pedres_docs/ChildrenLearnThruPlay.pdf].

- Jane McGonigal, "Gaming Can Make a Better World," TED2010 (video podcast), February 2010.

- Junaki Kumar and Mario Herger, Gamification at Work: Designing Engaging Business Software (Aarhus, Denmark: Interaction Design Foundation, 2013).

- Ibid.

- Max Lieberman, "Four Ways to Teach with Video Games," Currents in Electronic Literacy, Issue 2010: Gaming across the Curriculum (2010).

© 2015 Chas Grundy and Matthew Belskie. The text of this EDUCAUSE Review article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial license.