Key Takeaways

- Like its corporate counterpart, a higher education product manager is responsible for the entire service offering lifecycle, serving as a single point of contact.

- Serving as a user advocate, the project manager's goal is to make the product and corresponding experiences better for users.

- One of the product manager's most important qualities is the ability to bring many different people together to accomplish many different things.

Chas Grundy, Manager, Product Services, University of Notre Dame

In 2012, two years into his role as chief information and digital officer at the University of Notre Dame, Ron Kraemer noticed an interesting trend for IT services: The organization was adopting more software-as-a-service offerings used broadly across campus, constantly evolving, and integrated with many other departments or platforms.

These tools were not static and version-controlled; vendors sometimes rolled out updates and features with little or no notice. Many of them relied on constant change management and vendor relationships. Colleagues, both in and outside of IT, faced challenges in finding the right place to get help. Kraemer needed to find a new model for supporting and managing these services. Influenced by corporate and start-up practices, he created a new position: product manager.

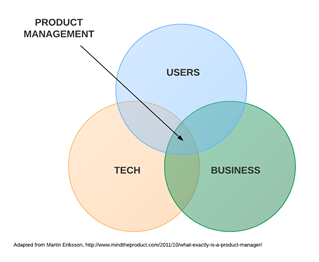

Like its corporate counterpart, a higher education product manager is responsible for the entire service offering lifecycle, which begins with strategy and product selection, continues through implementation and ongoing management, and finally concludes with the sunsetting of a service. Product managers are service owners in one sense, accountable for the success of the offering. Most importantly, they serve as a single point of contact for anything related to the product (figure 1).

Figure 1. Product manager as a single point of contact

The first two product managers at Notre Dame (including yours truly) focused on Box and Google Apps — two service offerings that had broad use across campus, but didn't fit neatly into any of the IT organization's existing management structures. The lack of a clear customer left these highly valued enterprise services underrepresented in IT. Product managers assumed the role of advocates, focusing on the customer's voice and gathering input, then representing customer interests within the IT organization.

As John W. McGuthry wrote in 2008, "the features and options of the service are rarely defined in the IT organization from the perspective of the end user."1 In other words, user experience is not a checkbox on a requirements list.

Today, the team includes four product managers in central IT, but the core responsibility has not changed. Serving as user advocates, our goal is to make the product and corresponding experiences better for users. The title and dedicated position of product manager are still new to Notre Dame, even across IT. While the group is involved in many projects and products, the expectations have not always been clear. Defining the role and boundaries has been a challenge, especially where we share service management with technical service owners or engineering teams. Building trust across teams is key to representing campus interests.

Effectively advocating for users requires listening to them and understanding their needs and desires. Before Notre Dame decided to move faculty and staff e-mail to Gmail, for example, the team met with more than 200 individuals from dozens of departments, holding individual interviews and group sessions to gather input. Product managers spoke with peers at many institutions that had moved to Gmail, as well as at organizations that had moved to competitors' services. They consulted with General Counsel on legal risks, the business office on the financial analysis, and campus IT support on the impact of establishing and supporting the tools. Only when confident that the move would provide a positive user experience, while still meeting the needs of the technology and business, did the organization commit to the move.

The Product Management Framework

Every product or service offering follows a natural lifecycle. This isn't a new concept, but as Harvard's Perry Hewitt observed in 2014, "Currently, too many digital initiatives suffer from a project-only approach. A website or service is stewarded until its launch, but there is little consideration of ongoing development and support."2 Project teams often hand off the keep-the-lights-on service management, potentially neglecting opportunities for continuous improvement that can benefit users, IT colleagues, and even budgets.

|

Strategy |

Concept |

Deployment |

Sustain |

Decline |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Understand the customers and their needs

|

Find a solution that meets customers' needs

|

Create, implement, and deploy the product

|

Support, measure, and continuously improve the product

|

Eliminate or replace based on the roadmap

|

The product managers spend about 30 percent of their time on projects, carrying out assessments (strategy), identifying solutions (concept), implementing solutions (deployment), or phasing out systems (decline). The remaining 70 percent is spent on sustaining products. Most of this time is spent with users. There is no substitute for going out on campus and visiting directly with end users, distributed IT staff, business managers, and others. Even better, watch users interact with your products, and you will open your eyes to how people actually use them.

Other ways to listen to your users, on a more quantitative scale, is through support tickets and website traffic. Which features do people ask for help on, and what does the website have to say on the matter? How much traffic are those pages getting? Do you offer training on the product? High support demand can be a symptom of a larger issue somewhere else in product management. Perhaps the training or help documentation leaves something to be desired, or customers are unaware of other options or features that might make their lives better.

Who Should Be a Product Manager?

On my office wall is a quote from Ken Norton, product partner at Google Ventures, about product management: "Your job is to be the advocate for whoever isn't currently in the room."3 Ken also commented, "Product management is a weird discipline full of oddballs and rejects that never quite fit in anywhere else." This one isn't printed on my wall, but it's on my mind as I think about why our role works as well as it does.

The skills required of product managers are different than many traditional IT roles, largely because of the breadth of their responsibilities. The recipe isn't perfect, but it generally comes down to a few key elements: listening, leadership, communication, and passion.

The first responsibility of a product manager is to listen — to users, technologists, and administrators. We are also problem-solvers, so this can be tough. After all, if you're jumping ahead to your solution, then you're no longer listening. When every conversation becomes an echo of the previous one, you know you're onto something.

Product managers rarely manage people; they rely on help from across the organization. The product lifecycle includes many different activities, and the product manager cannot do them all. One of the product manager's most important qualities is the ability to bring many different people together to accomplish many different things. At St. Louis University, product management implemented new HIPAA controls that required collaborations between campus stakeholders, legal, information security, and IT engineers.

Many managed products in higher ed hinge on a third-party vendor's roadmap. Perry Hewitt described product management in higher education, noting, "[E]ven though the technology roadmap is beyond our control, there are still decisions to be made."4 Product managers own these decisions. Successful vendor management relies on building and maintaining relationships not just with the supplier but also often with peers and other customers of the vendor. Lobbying for feature requests may be far easier if combined with requests from many other institutions.

Another key trait of a product manager is strong marketing — and presentation — skills. Because products evolve, the IT organization must educate and train users, and even promote these tools. Many organizations have recognized that sending more e-mails to the campus community doesn't necessarily mean everyone will read them. Product managers, then, seek appropriate ways to communicate, and sometimes build excitement around, change.

A product manager might write documentation, meet with executives, teach a training class, and research a support solution, all in one day. This variation in tasks means that a product manager could come from any number of backgrounds. As my team has grown, I have sought one particular trait: passion. If a candidate is passionate about something and can convey that excitement to others, then he or she might make a great product manager.

What Kinds of Products Need Product Management?

With any new role, especially one as broad as product management, it isn't always clear which services would benefit most from this approach. Products that truly need a product manager lack a clear customer (often because everyone is a customer), have broad use across campus, and frequently change or evolve. At Notre Dame, this tends to lean toward SaaS and PaaS solutions, in support of a cloud-first strategy.5 In many cases, no technical staff on campus possess in-depth knowledge of the service.

For services or applications with an obvious customer, the demand for innovation is more or less external to IT. Requirements, customer satisfaction, and feedback come to us whether or not we ask for them, and we provide solutions that best meet the business, budget, and user needs. In these cases, the product management framework can help ensure that we deliver the best possible solution and manage it through the entire lifecycle.

The St. Louis University Enterprise Products Group includes half a dozen product managers, including Angel Magee, e-mail product manager. Rather than select products to manage, the group assumes that every product needs product management — though not necessarily a dedicated product manager. Still, the role is that of user advocate. Magee agrees: "The easiest and best solution for users sometimes isn't the best solution for IT."6

If a product has limited use on campus, it may not warrant the resources that go with a full product management approach. However, these products may be easier to manage and can be relatively hands-off. In deciding whether product management is needed, one good question to ask is whether the limited use indicates poor awareness and adoption or if the product fails to meet the needs of the wider user community. In either case, product managers can be helpful.

The most compelling case for using a product manager is when the product evolves frequently, requiring significant and ongoing change management. This kind of change can be disruptive and frustrating to users, but it can also be a tremendous opportunity to excite and delight them. Users' needs also evolve, and vendors work to make sure their products keep pace with changing needs and expectations. Product managers stay attuned to these changes through vendor management, monitoring industry sources, and staying in touch with customer communities. This regular contact may even provide avenues to influence change within the product and vendor behavior, making users even happier.

In the example of Notre Dame e-mail and calendaring, conversations with campus constituents revealed that faculty and staff were deeply unsatisfied with the existing service because of amount of mailbox quota, calendar support on mobile devices, and uneven usability on Mac and Linux devices. This drove our team to change direction, find a new solution, and eventually migrate faculty and staff to Google Apps. Acting as a proxy for our customers, product management helped drive the service strategy, deployment approach, and ongoing maintenance of the product.

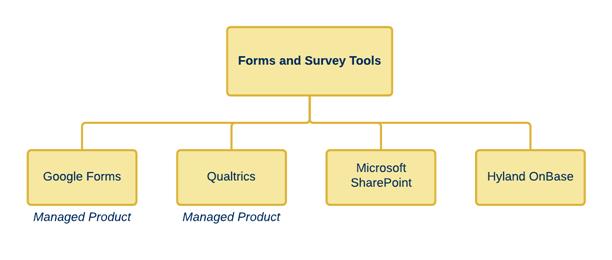

Today, Notre Dame has a growing portfolio of services and products with dedicated product managers, including e-mail, calendaring, end-user data and file storage (e.g., Google Drive and Box), end-user data backup, forms and survey tools, and web publishing. Larger systems such as Google Apps offer more than one service, and we have more than one product manager working on it. Other services, such as the Forms and Survey Tools, include offerings that are handled perfectly well outside of product management (see figure 2). In those cases, these groups work together to provide a positive customer experience and apply the product management framework as appropriate.

Figure 2. Services with and without product management

Advice for New Product Managers

After three years of product management in IT, I'd offer a few key bits of advice for a new product manager:

- Get out and listen to as many different users, stakeholders, and colleagues as possible. Spend weeks or months meeting with people on their turf and asking questions.

- The most important question is, How can I help you? You'll get a wide range of answers depending on who you ask, so be careful in how you balance them.

- Jump in and help wherever you can. Contribute to other projects, volunteer at the help desk, and learn as much as you can along the way. You want people to recognize you as a valuable resource that can make their lives better.

- Build relationships because you will inevitably step on toes or bulldoze someone else's good intentions. These are unavoidable missteps, but easily survived if you have earned trust so that people know you're acting in your users' best interests.

- Create fun through the attitude you bring to the team. You are making change happen, which is disruptive and painful. But change for the right reasons can be exciting and enjoyable. Help people appreciate these changes by making them fun and focusing on the positive.

Creating Fun

When Notre Dame took faculty and staff to Gmail and Google Calendar in 2014, IT launched the Google Apps Jedi Academy, complete with Jedi cartoon characters, Jedi ceremonies, and prizes. This training program tested campus IT staff on knowledge of the new Google platform. Each test moved participants up the ladder of Padawan, Jedi Knight, Jedi Master, or Yoda. Of the 237 people who participated in the program, 207 of them achieved Yoda status. One IT colleague sent her feedback: "It was a fun addition to make the transition a bit more bearable!"

When Notre Dame took faculty and staff to Gmail and Google Calendar in 2014, IT launched the Google Apps Jedi Academy, complete with Jedi cartoon characters, Jedi ceremonies, and prizes. This training program tested campus IT staff on knowledge of the new Google platform. Each test moved participants up the ladder of Padawan, Jedi Knight, Jedi Master, or Yoda. Of the 237 people who participated in the program, 207 of them achieved Yoda status. One IT colleague sent her feedback: "It was a fun addition to make the transition a bit more bearable!"

From Product Managers to Product Advisors

Working alongside traditional service owners, help desk staff, support staff, business managers, and engineers, product managers navigate the organizational chart, hopping boundaries and dodging silos, to get a perspective that represents end user, business, and technical viewpoints — and each to the others. By listening to your customers, you gain a crucial understanding of where IT can offer the most value, what your users care about, and how you can better meet user needs. By understanding the business of the organization, product managers look for prudent solutions and campaign for funds when appropriate (offering savings where possible). Through partnerships across the technical organization, you can find momentum in making change to systems and tools that might have been around for decades. Finally, for CIOs balancing the needs and constraints of users, technology, and administration, product managers can be an invaluable resource representing all three.

When I started in product management at Notre Dame, I met with Ron Kraemer, who described the new role:

"When I think of the best service I have ever received, I think about a welcoming hotel concierge. It doesn't matter what I need; if it is associated with making my time at the hotel most pleasant, the concierge helps. I think of a product manager in much the same way. If you have a question, need help, or want to request something with one of our services, our product manager is your concierge."

- John W. McGuthry, "Product Managers in I.T. Organizations," EDUCAUSE Evolving Technologies Committee, November 2008.

- Perry Hewitt, "Setting the Stage for Digital Engagement: A Five Step Approach," EDUCAUSE Review, vol. 49, no. 5, September 15, 2014.

- Ken Norton, "How to hire a product manager," kennethnorton.com, 2005.

- Hewitt, "Setting the Stage."

- Cloud First [http://oit.nd.edu/cloud-first/], Office of Information Technology, University of Notre Dame.

- Conversation with the author, April 13, 2015.

© 2015 Chas Grundy. The text of this EDUCAUSE Review article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) license.