Key Takeaways

- This case study provides a glimpse of the layered approaches to university-wide educational technology training and course development (including online and blended course development) instituted at Western Washington University.

- The array of opportunities for faculty professional development at WWU span formal campus-wide training to spontaneous peer-to-peer mentoring, crossing institutional layers to support integrated technology.

- On-demand help or impromptu sharing of information led to unexpected learning and the exploration of another technology, supplementing more formal workshops and training.

- Modeled after open gyms, themed open computer labs staffed with experts allowed individuals to drop in during a two-hour window and receive answers to their specific questions.

At Western Washington University Andrew Blick is e-learning and assessment specialist, Extended Education; Paula Dagnon is director of Instructional Technology, Woodring College of Education; Don Burgess is associate professor, Department of Secondary Education; Justina Brown is instructional designer, Multimedia and Faculty Development; and Matthew Miller is associate professor, Department of Elementary Education.

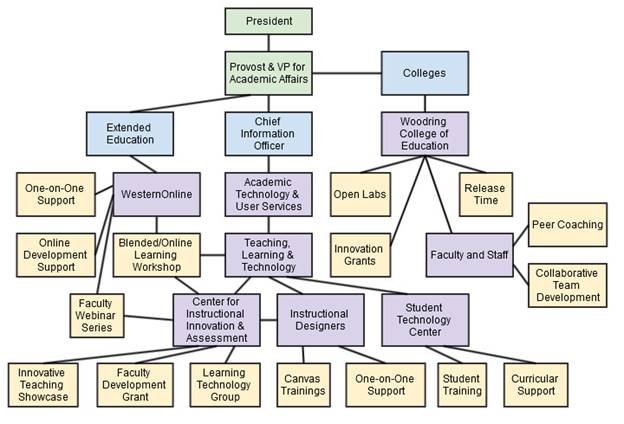

Higher education professionals increasingly design courses while taking into account rapid changes in student needs and demographics, instructional technologies, and institutional expectations. Supporting this challenging work with a variety of professional development opportunities is an essential solution for educators as they respond to these needs. Western Washington University's (WWU) layered approaches to faculty development connects educational technology training and course development, emphasizing instructional design, pedagogy, and development of technical skills. The array of opportunities for professional development span from formal campus-wide training to spontaneous peer-to-peer mentoring. Multifaceted efforts cross institutional layers (as illustrated in figure 1) in support of integrated technology, producing an academic community with consistent and equitable access to technology and pedagogical support.

Figure 1. Cross-institutional integration of technology at WWU

Characterizing Western Washington University

WWU is a regional public university located in Bellingham, Washington. The 15,000 students benefit from a 21:1 student-to-faculty ratio and relatively small classes (75 percent of classes have fewer than 30 students). The campus has a liberal arts foundation and opportunities for faculty, staff, and students to develop professional skills. Students may choose from 160 academic programs offered by seven colleges.

WWU provides various levels of support for developing blended and online courses through the offices of Academic Technology and User Services (ATUS), the Center for Instructional Innovation and Assessment (CIIA), and Extended Education (EE), among others. This support includes, but is not limited to, workshops, training, and individual consultations/development on a variety of best practices, current trends, and innovative uses of tools and applications in educational technology.

University-wide Professional Development

Various campus groups offer faculty development workshops as webinars and small-group training. Many of these development opportunities are tied directly to the mission of the sponsoring office(s). For example, the office of Extended Education and disAbility Resources for Students offers workshops specifically geared toward universal design and accessible uses of technology in online and blended courses. This programming allows faculty and staff interested in a specific tool or best practice to attend a short workshop (one to two sessions) focused on specific tools.

Available funding and resources vary at different institutions for use in faculty development and training. Some development ideas can be completed from low- to high-budget levels of funding and support, such as the programs noted in table 1.

Table 1. Low- and high-budget options for a faculty development workshop

|

Sample Learning Outcome: Faculty will be able to design components of their course, incorporating best practices of instructional design. |

|

|

Low-Budget Program Idea |

A series of mini-workshops similar or a workshop that follows an established curriculum. Faculty from various arenas could be invited to participate and contribute their expertise. Faculty attendees could be awarded certificates of completion if the workshops were structured in a way that would provide the facilitators with measurable outcomes. |

|---|---|

|

High-Budget Program Idea |

Faculty could receive stipends and/or incentives for participation, additional resources and materials, and possibly conference sponsorship. |

Some of the professional development examples from WWU fit into this high-budget level, including the Faculty Development Summer Grant, while others require moderate funding, such as the Blended/Online Learning Workshop, and some involve minor operating expenses, such as the Innovative Teaching Showcase and the self-paced Programming for Faculty and Students.

Faculty Development Summer Grant

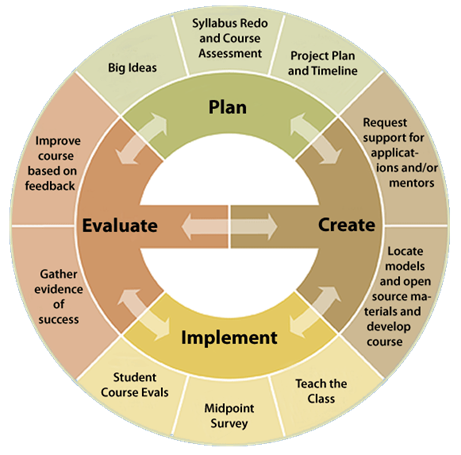

Faculty at WWU have the opportunity to apply for Faculty Development Summer Grants through the CIIA. In 2010, the Provost's Office encouraged the CIIA to facilitate a grant-based workshop for faculty wanting to implement strategic uses of the web to enhance their existing courses. This was partly inspired by the U.S. Department of Education meta-analysis finding that courses blending online tutorials and support with traditional face-to-face instruction yield higher student achievement than stand-alone face-to-face courses. Continued evidence from the literature1 and positive responses from grant participants paved the way to repeat this program for each of the past five years. The Faculty Development Summer Grant involves a five-day, on-campus intensive training on instructional design and campus-supported technologies provided by CIIA and ATUS, followed by development of a course transformation with assistance from these offices, as noted in figure 2.

Figure 2. Summer Grant support for the planning and creation phases of course transformation

During the application process, instructors are encouraged to focus on large courses (75 students or more) and/or gateway courses with high failure rates or difficult material. A faculty advisory board reviews applications, and the grant ultimately serves about 12 faculty members per year. Each workshop participant leaves the week-long workshop with a clarified vision of their course enhancement, how it will support student learning outcomes, and how to best utilize the LMS and other technologies (lecture capture, web conferencing, web-based tools, etc.) to enhance collaboration and evaluation. A highly rated aspect of this workshop is the sense of cross-disciplinary community and support each participant experiences.

Summer Grant Transformation: Academic Language Modules

Don Burgess's review of the Academic Language Modules (3:10 minutes)

One successful proposal involved the creation of six blended modules centered on academic language — the oral and written language used to describe abstract and complex ideas, which varies across content areas.2 Two faculty from the Woodring College of Education (WCE) collaborated to build blended instructional modules in Canvas that candidates access in 10 Secondary Education methods courses. Students must learn the language of their discipline because it is the only way they can engage and participate in each subject area. Since academic language is a core component of the courses leading to Secondary Teacher Certification, the modules effectively support 150 students a year. Academic language is also a key component of the new Teacher Performance Assessment (edTPA), which is now required for teacher certification in Washington.

Simple exposure to academic language in the classroom does not reach all students. The online modules help pre-service teacher candidates in Secondary Education learn appropriate strategies and tools. The modules show candidates how to explicitly and consistently support the language demands of their lessons. Candidates learn to how help all students gain access to the content they teach using strategies and tools such as graphic organizers, sentence stems, modeling, practice with immediate feedback, etc.

Blended/Online Learning Workshop

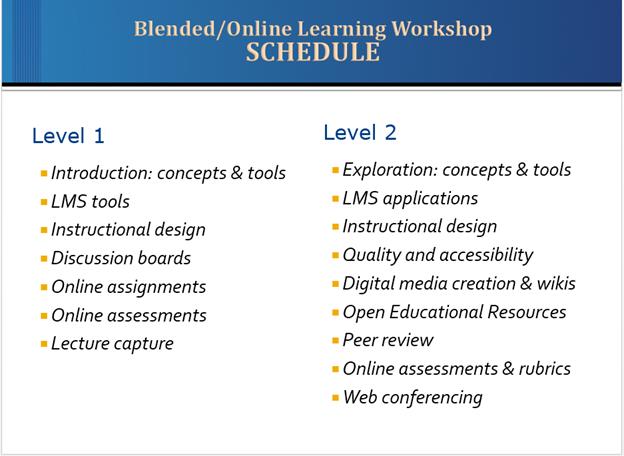

In 2011, a multi-unit collaborative initiative was started by ATUS, CIIA, and EE to create an experiential workshop to give a faculty cohort of 15 participants an overview of methods and practices related to blended and online learning and teaching. This Blended/Online Learning Workshop engaged faculty in collaborating and making connections with other faculty across disciplines. The workshop provided an opportunity to experience a blended format while concurrently developing blended or online format courses. The facilitators designed this workshop to be independent of a specific learning management system, integrating elements of WWU's current learning management system (Canvas by Instructure) with instructional design techniques and principles.

The workshop, now in its fourth year, has evolved into a two-level program (see figure 3). Level 1 focuses on the development of the blended/online course syllabus, general organization of the course, and the course map; selection and development of course content; and creation of assignments and student assessments. Level 2 focuses on integrating new media, peer review and group assignments, facilitating web conferences, reviewing and revising courses, and other specific topics related to participants' interests. (See the workshop syllabus for additional information.)

Figure 3. Schedule for Level 1 and Level 2 of the Blended/Online Learning Workshop

On completion of the workshop, participants receive a small monetary stipend and a certificate of completion. Participants gave high reviews to the tools, information, and cross-disciplinary connections made as a result of the workshop. As a participant, co-author Don Burgess found the collaboration within and between participants engaging and appreciated seeing the deep-seated beliefs about learning, teaching, and assessment revealed. As a facilitator, co-author Andrew Blick found the most rewarding piece to be observing faculty implement in their courses and curriculum the skills and materials developed in the workshop.

Innovative Teaching Showcase

In 1999, the CIIA started the Innovative Teaching Showcase online publication as a way to highlight and share exceptional teaching practices by Western Washington University faculty. Each year, several instructors are nominated to participate within the context of a theme, and then work extensively with the CIIA to create this in-depth resource. The website (see figure 4) includes short video interviews with each instructor as well as a written "portfolio" documenting their innovative approach (complete with syllabi and assignments). The collection of best practices includes open access to course materials and the instructor's insights related to themes such as peer learning, civic engagement, social justice, blended learning, and sustainability. Instructors get no funding for participation; however, most instructors comment on the inherent value of reflecting on their teaching practice and organizing their materials to share. Now in its 15th year, the Innovative Teaching Showcase has featured over 50 instructors from WWU.

Figure 4. Home page for the 2013–14 Innovative Teaching Showcase featuring three WWU instructors

Showcase: Paula Dagnon

Paula Dagnon's Innovative Teaching Showcase feature (4:01 minutes)

One of the featured instructors of the recent Showcase and also one of the co-authors of this article, Paula Dagnon presented her course design, content, and reflections (via the portfolio and video interview) for her blended course.

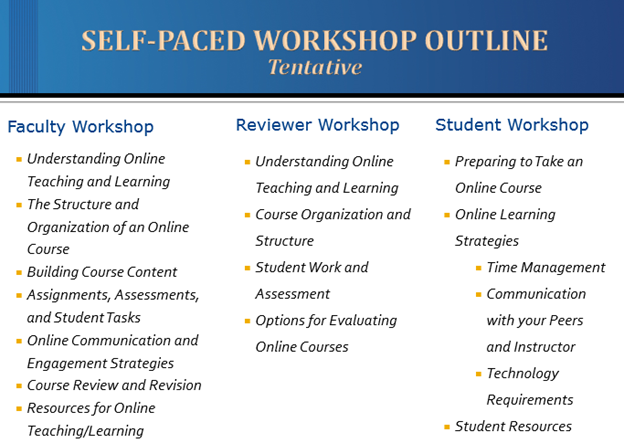

Self-Paced Programming for Faculty and Students

New online, self-paced workshops are in the process of being designed for faculty developing online offerings, academic administrators (chairs, academic program directors) who oversee faculty teaching online courses, and students interested in enrolling in online courses. These workshops will lead participants, who may be unfamiliar with blended/online courses, through a series of learning modules developed to introduce them to best practices for online/blended learning, current trends in distance education, and assessment techniques. The objective of these workshops is to provide tools and techniques related to online teaching and learning (see figure 5).

Figure 5. Tentative workshop outline for Self-Paced Programming

College and Departmental Support: Innovation Grants

While each college may take different approaches to supporting faculty in the use of technology for online and blended courses, Woodring College of Education (WCE) recently used three college-wide strategies worth discussion: innovation grants, technology open labs, and release time or compensation for course and program development.

Peer-Mentoring Grants

For the past two years, WCE has allocated funds for innovation grants. While the criteria for these grants did not specifically focus on technology, in both 2012 and 2013 technology initiatives received the largest level of funding.

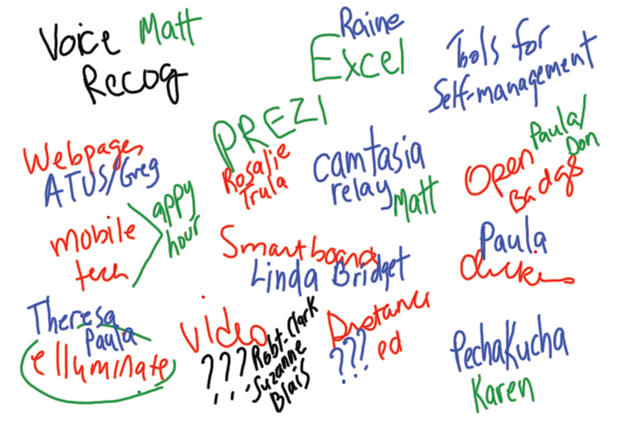

As a result of the Innovation Grants, in 2012 a call went out to the entire college for faculty to join a Woodring Coaches of Technology (WCOT) group in order build capacity for technology integration. For participating in monthly meetings, 10 faculty members would receive an iPad and a stipend for apps. At the initial meeting, participants used technology including smart boards and iPads to collaboratively develop themes (see figure 6) as well as to volunteer to mentor around one of the themes. In the accompanying video, Matthew Miller shares his experience in the coaches program as both a participant and a mentor.

Figure 6. College faculty used collaborative tools to generate themes during a WCOT meeting.

Matthew Miller's experience with the WCOT group (3:10 minutes)

While each meeting had an agenda, which always included "Appy hour" where colleagues shared their favorite apps, unexpected learning occurred where on-demand help or impromptu sharing of information led to the exploration of another technology.

Shared expertise strengthened this model, with the coaches contributing their knowledge not only to each other and the two organizers but also to other colleagues as they stood by the copier, passed each other in the stairwell, and conferred in faculty offices. While many elements of this model led to success, two primary challenges arose:

- Scheduling and trying to find a time where 10 faculty members and two coordinators could meet. Ultimately, to meet the goals of the grant, we created a menu of options for learning and teaching with technology, including attending webinars, other on-campus technology-related workshops, and mentoring a peer, among other options.

- Differentiating skills and information for both novices and experts. Like classroom teaching, the skills of the participants varied from those who had never used an iPad to a few who might define themselves as "early adopters." The menu of options we created for participants to meet the goals of the grant also allowed the more technology-literate participants to challenge themselves. Participants documented their learning in a variety of ways on a team wiki.

Table 2. Low- and high-budget options for a mentoring program

|

Sample Learning Outcome: Mentee: Faculty will plan their online/blended courses in conjunction with a senior faculty mentor. Mentor: Faculty will support new faculty to master the online/blended modality. |

|

|

Low-Budget Program Idea |

A more experienced faculty member paired with a newer faculty member would help explain online/blended learning. This mentor could answer curriculum- and instruction-related questions. |

|---|---|

|

High-Budget Program Idea |

Faculty could receive a stipend and/or departmental service credit to undertake a mentor role. Additional training related to mentorship and instructional design, among other topics, could be provided to teams. |

Technology Open Labs

The Woodring College Technology Committee implemented a second initiative to support faculty with skill acquisition by creating open labs (figure 7). Modeled after open gyms, where athletes come to a gym to work on a self-identified skill set and to improve their game, themed open computer labs staffed with experts allowed individuals to drop in during a two-hour window and receive answers to their questions.

Figure 7. Open lab promotional sign

Both college faculty and academic technology support personnel staffed these labs to provide just-in-time support. While significant learning occurred as a result of the differentiated support based on need and collaborative conversations, the challenge with this model is the deep knowledge required by the supporting faculty and staff. With an average of 10 participants per open lab session, we found the engagement and collaboration among participants and facilitators well matched. Unlike open gyms where athletes with a range of skills practice collaboratively, we found that open computer labs typically attract individuals with lower technical skills and diverse needs. This places the onus for mentoring entirely on the open lab faculty and staff support persons.

As a participant in the open labs, Burgess commented, "Open labs are a great place to receive and offer just-in-time support. In fact, a colleague asked me to accompany her to the open lab to work on a specific task. When we arrived at a technical problem, we were able to receive immediate support allowing us to continue working." As a facilitator of the open labs, Dagnon found it difficult to prepare for these labs, not knowing in advance what type of support might be needed. Additionally, without multiple facilitators attending the labs, at times participants would sit idle until help was available, if other participants could not answer their questions. Table 3 shows options for mobile device app training, from a roundtable to a workshop, by colleges or departments with varying levels of funding and support. Table 3 shows the options for app training.

Table 3. Low- and high-budget options for mobile device app training

|

Sample Learning Outcome: Faculty will be able to evaluate and implement apps in their classrooms. |

|

|

Low-Budget Program Idea |

Bring Your Own Device (BYOD) Roundtable:

|

|---|---|

|

High-Budget Program Idea |

App Workshop and Implementation:

|

Compensation for Course and Program Development

A third mode of support for faculty to enhance their skills with technology for blended and online support again requires funding. In many instances, our faculty have received a course release in order to improve a course or to develop new programs. In cases where course releases are not viable, faculty stipends have been awarded to faculty committed to developing or enhancing their courses with or through technology.

One-on-One and Small-Group Consultations

Another avenue for faculty development across contexts includes peer and one-on-one development, as well as small-group consultations. These approaches can particularly benefit faculty at outreach sites or non-tenure–track faculty who might not be eligible for some of the funded opportunities.

Consultations

One of the most common models for blended/online course development is one-on-one or small-group consultation. This form of support can extend the layers of support already outlined. During these consultations, an instructional designer is paired with a faculty member to work through the development process. The faculty member creates the content, assignments, and assessments, while the instructional designer helps move materials to an online environment, offers suggestions and ideas for development, and provides general assistance throughout the process. These consultations are tailored to faculty members' specific needs and skill sets. This process generally spans multiple cycles of the instructional design process, including a development phase, initial offering, and revision phase.

One-on-one follow-up consultations are part of the design model for the Faculty Development Summer Grant. These meetings allow participants to work through course decisions with an instructional designer, get deeper instruction on a particular instructional or technological strategy, or make a plan for continued support, possibly with other professionals who have specialized knowledge.

Faculty may also work in teams with an instructional designer to collaboratively develop course content. This collaborative approach brings in many individuals' strengths, but it also introduces new challenges to the development process (table 4).

Table 4. Strengths and challenges of Faculty Development Teams

|

Strengths |

Challenges |

|---|---|

|

|

Conclusion

This case study provides a glimpse of the layered approaches to educational technology training and professional development (including online and blended course development) instituted at WWU from our perspective as facilitators and participants. We hope that the descriptions of university-wide, college-level, and one-on-one/team support will stimulate further thinking, conversations, and program development at similar institutions. The low- and high-budget program descriptions provide alternatives for institutions of varying sizes and structures as they implement programs that support staff and faculty innovation.

As assessment practices continue to emphasize formative assessment and feedback, faculty increasingly turn to blended and online solutions. Many of the ideas presented here can serve as foundational elements for institutions, providing a more active response to student needs consistent with equitable access to technology.

- Patricia McGee and Abby Reis, "Blended Course Design: A Synthesis of Best Practices," Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, Vol. 16, No. 4 (2012): 7-22.

- Jeff Zwiers, Building Academic Language: Essential Practices for Content Classrooms, Grades 5-12 (Wiley.com, 2008).

© 2014 Andrew Blick, Paula Dagnon, Don Burgess, Justina Brown, and Matthew Miller. The text of this EDUCAUSE Review online article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivativeWorks 4.0 license.