![E-Content [All Things Digital] E-Content [All Things Digital]](http://www.educause.edu/apps/er/images/e-content2010.jpg)

Dan Cohen is the Founding Executive Director of the Digital Public Library of America (DPLA).

The vision of a national digital library has been circulating among U.S. librarians, scholars, educators, and technologists since the early 1990s. Efforts led by a range of organizations—such as the Internet Archive, HathiTrust, and others—have successfully built resources that provide books, images, historical records, and audiovisual materials to anyone with Internet access. Scores of institutions have digitized vast numbers of materials held in U.S. libraries, archives, and museums, making available a shared cultural heritage in ways unimaginable not so long ago.

However, these digital collections often exist separate from one another, with each offering its own interfaces, search mechanisms, and underlying data structures. Starting in 2010, leaders from libraries, foundations, academia, and technology agreed to work together to create "an open, distributed network of comprehensive online resources that would draw on the nation's living heritage from libraries, universities, archives, and museums in order to educate, inform, and empower everyone in the current and future generations."1

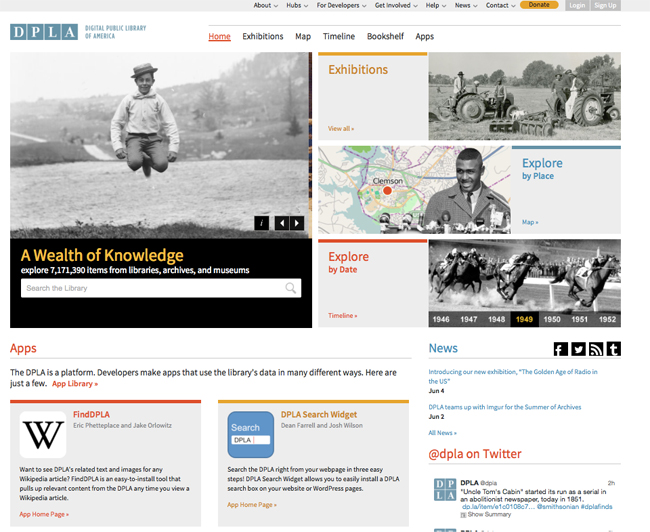

The Digital Public Library of America (DPLA), which launched on April 18, 2013, with lead funding by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, unites these disparate collections, providing open and coherent access to the country's digitized cultural heritage. As of this writing, DPLA has over 7 million items, a number that grows every week. It displays them through its portal and also redistributes those items through its platform, which includes an API (application programming interface) and open data.

DPLA normalizes and enhances the records of contributing institutions so that they can be commingled and made more easily discoverable through innovative interfaces. For instance, DPLA provides geocoding (latitude and longitude) for as many items as possible. This means that users can browse and search DPLA's unified collection through its map, which is not possible elsewhere. Researchers can also browse using the timeline, virtual bookshelf [http://dp.la/bookshelf/], and faceted search tools. In addition, teachers and students can save and share customized lists [http://dp.la/info/help/accounts/] of their favorite items and explore curated digital exhibitions on subjects of national significance.

Developers enjoy complete access to the full collection via the API and a bulk download page, and they have responded by building a range of apps, demonstrating how the role of a digital library can be much more than a simple storehouse of, and interface for, digital collections. For instance, Culture Collage [http://dp.la/apps/7] allows users to search DPLA image holdings and display the results as a dynamic river of images from which users can save their favorites into a Pinterest-style page. Other apps offer easy DPLA integration with landmark web services, such as FindDPLA [http://dp.la/apps/19] for Wikipedia and WP DPLA [http://dp.la/apps/10] for WordPress. OpenPics, a smartphone app, utilizes the phone's GPS signal to show DPLA materials that come from the area around a user. All of these DPLA-powered apps can be found in the ever-expanding app library [http://dp.la/apps].

A Network and Community

DPLA accomplishes its mission by aggregating metadata and thumbnails pointing to digital objects for millions of photographs, manuscripts, books, sounds, moving images, and more from a national network of partners. This network comprises individual nodes, or hubs [http://dp.la/info/about/hubs/], which work with DPLA to map and ingest their records into the DPLA repository.

There are two types of hubs: service and content. Service hubs are state or regional digital libraries that collect items from organizations across their respective state or region, in addition to providing a trove of essential services including digitization, metadata consultation and enrichment, community organization, and technology support. Content hubs hold hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of digitized items on their own. Unlike service hubs, which interact with DPLA on behalf of myriad smaller regional organizations, content hubs represent themselves only and commit to providing DPLA with at least 200,000 items. This approach to infrastructure management allows DPLA to maintain a sustainable number of partnerships while maximizing existing data practices and local expertise in hub locations.

The hubs are a key part of a national community of people who actively support the very principles on which DPLA operates, especially a strong belief in libraries' "public option" for reading and research. This long-standing attention to public engagement is manifested as well in DPLA's community reps program, an outreach initiative that has put in place an all-volunteer corps of DPLA advocates, spanning many professional domains and user communities including state libraries, public libraries, K-12 schools, colleges and universities, and technology, library, publishing, media, and genealogical organizations. DPLA reps now hail from all 50 states and 5 countries outside the United States.

DPLA's home page

Post-Launch Growth and Year Two

In the year since DPLA launched, we exceeded our expectations and tripled the size of our collection, jumping from 2.4 million items to over 7 million. We now pull in materials from over 1,200 organizations, up from 500 at launch, and in April 2014, we announced that six new partners—California Digital Library, Connecticut Digital Archive, Indiana Memory, Montana Memory Project, the Government Printing Office, and The J. Paul Getty Trust—either had teamed up with DPLA as content hubs or service hubs, or were joining an existing service hub. All will help to greatly expand our offerings from their respective regions, contributing numerous new items and bolstering the distributed national infrastructure. As of April 2014, the website has attracted over 1 million unique visitors and over 9 million hits to the API. We expect both of those numbers to increase substantially in the coming years, but hubs already report a surge in traffic to their holdings after joining DPLA. Mountain West Digital Library, for example, doubled its traffic in the first year and now receives more traffic from DPLA than from Google.

Our foremost goal for year two is to work toward completing the national network of hubs, which will in turn grow the collection even more and provide on-ramps to DPLA for collections across the nation. We are also in the process of optimizing DPLA's back-end systems to allow for increased capacity for ingestion of new collections.

In addition, we are seeking to make progress on rights and rights statements. Large-scale collections like DPLA, Europeana, Trove, and DigitalNZ have enriched the free web by making openly available tens of millions of items from libraries, archives, museums, and cultural heritage sites. This burgeoning public commons is weakened, however, by a lack of common agreement on rights statements regarding these items, by inconsistent international copyright law, and by risk aversion among many nonprofit institutions. Working alongside these other national and international projects, we at DPLA intend to harmonize and evangelize a simpler rights structure, one that includes ways for works of all types, including materials with unclear or no known rights, to be made available to the public.

On another front, we are working with our hubs to provide digital skills training for public librarians and connect them with state and regional resources for digitizing, describing, and exhibiting their cultural heritage content. Funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Public Libraries Partnership Project is designed to reach public librarians who want to share their libraries' special collections content with a broader audience but may not have the resources to do so. One result of this project will be a replicable practicum that librarians and other information professionals can use remotely, wherever they may be.

Finally, in our second year we will explore potential sustainability models and, in turn, pursue the most promising option (or options). Thanks to a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, we will expand our staff to target opportunities for further development and revenue, without compromising our mission of open access to the riches of America's libraries, archives, and museums. DPLA's ambitious coast-to-coast accumulation of openly available materials will take years to bring together and to put into educational contexts and public programs; achieving a sustainable model will be critical to fulfilling that mission.

Conclusion

DPLA delivers an innovative experience for students, educators, researchers, and others to interact with the combined riches housed in the most cherished institutions of the United States. As we move forward in our second year of operation, we encourage you to make use of DPLA's ever-growing collection of open-access materials—through our site, or another site or app powered by our API—and to become a part of the project, whether as an individual or an organization.

- "Sign On," DPLA Planning Initiative Wiki. For background on the early planning of DPLA, see Rachel L. Frick, "Enabling Noncompetitive Collaboration at Web Scale," EDUCAUSE Review, vol. 46, no. 3 (May/June 2011).

© 2014 Dan Cohen. The text of this article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

EDUCAUSE Review, vol. 49, no. 4 (July/August 2014)