Key Takeaways

- One of the Australian national virtual laboratories, the Humanities Networked Infrastructure brings together data from 30 different data sets containing more than two million records of Australian heritage.

- HuNI maps the data to an overall data model and converts the data for inclusion in an aggregated store.

- HuNI is also assembling and adapting software tools for using and working with the aggregated data.

- Underlying HuNI is the recognition that cultural data is not economically, culturally, or socially insular, and researchers need to collaborate across disciplines, institutions, and social locations to explore it fully.

Toby Burrows is manager of eResearch Support at the University of Western Australia. Deb Verhoeven is professor of Media and Communication at Deakin University.

The Humanities Networked Infrastructure (HuNI) is one of the national "virtual laboratories" being developed as part of the Australian government's NeCTAR (National e-Research Collaboration Tools and Resources) programme. NeCTAR aims to integrate existing capabilities (tools, data, and resources), support data-centered workflows, and build virtual communities to address well-defined research problems. This is a particularly challenging set of technical requirements and problems for the humanities and creative arts, which cover an extensive range of different disciplines and are characterized by complex and highly heterogeneous collections of data.1 User requirements and use cases are also very varied and complex.

HuNI is being developed by a consortium of 13 Australian institutions, led by Deakin University. It brings together data from 30 different Australian data sets, which have been developed by academic research groups and collecting institutions (libraries, archives, museums, and galleries) across a range of disciplines in the humanities and creative arts (including, but not limited to, literature, visual arts, performing arts, cinema, media, and history). These data sets contain more than two million authoritative records, capturing the people, places, objects, and events that make up the country's rich heritage.

HuNI is ingesting data from all these different Australian data providers, mapping the data to an overall data model, and converting the data for inclusion in an aggregated store. HuNI is also assembling and adapting software tools for using and working with the aggregated data.

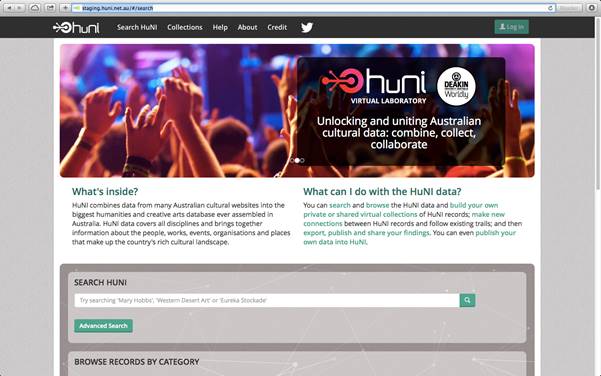

Fundamental to HuNI's architecture was the decision to build a central aggregate, rather than designing the virtual laboratory functionality around federated searching. A central aggregate adds significant value to the disparate data sources by maximizing the links between them and by putting them into a much broader interdisciplinary context. It also enables researchers to work with data from a variety of different sources in a much more effective way and on a much larger interdisciplinary scale. Figure 1 shows a screenshot of the HuNI interface.

Figure 1. HuNI home page

HuNI is part of the rapidly growing global digital humanities initiative, which is producing many innovative applications and services aimed at expanding the use of digital technologies in humanities research. In Australia, this expansion saw the formation of the Australasian Association for Digital Humanities (aaDH) in March 2011, its formal incorporation in March 2012, and its acceptance into the international Alliance of Digital Humanities Organizations (ADHO). Many of the researchers involved in the HuNI initiative were also involved in the formation of aaDH.

Data Integration

The 30 Australian humanities data sets being incorporated into HuNI are managed and maintained by a variety of different institutions, including various universities and government agencies like the Australian Institute for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS). Data providers also include several national consortia in specific humanities disciplines, including AustLit (managed by the University of Queensland)2 and AusStage (managed by the Flinders University of South Australia).3 The data from some of these services conform to standard metadata schemas like Dublin Core, EAC-CPF (Encoded Archival Context – Corporate bodies, Persons, and Families), and MARC-XML (Machine Readable Cataloguing – eXtensible Markup Language). Many of the other data services are in a customized format specific to that data set.

Table 1 lists the various data sets, their metadata schema, and their custodian or owner. The table also shows the type of data contained in each data set.

Table 1. List of HuNI Data Sources

|

Data Set |

Schema |

Data Type |

Custodian or Owner |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Australian Dictionary of Biography (ADB) |

EAC-CPF |

Biography |

Australian National University |

|

AusStage |

Custom |

Performance |

Consortium led by Flinders University |

|

AUSTLANG |

Custom |

Linguistic |

AIATSIS |

|

Mura |

Custom |

Language |

AIATSIS |

|

AustLit |

FRBR-derived |

Literature |

Consortium led by University of Queensland |

|

Design and Art Australia Online (DAAO) |

EAC-CPF |

Biography |

Consortium led by University of New South Wales |

|

BONZA |

Custom |

Cinema and TV |

Deakin University |

|

CAARP |

Custom |

Cinema |

Consortium led by Deakin University (in association with Flinders University) |

|

Dictionary of Sydney |

Custom |

History, Geography |

Consortium led by Dictionary of Sydney Trust |

|

PARADISEC |

OLAC / RIF-CS |

Linguistics |

Consortium led by University of Sydney |

|

Media Archives Project |

Dublin Core |

Media Industry |

Macquarie University |

|

Australian Media History Database |

Custom |

Media Industry |

Macquarie University |

|

Encyclopedia of Australian Science |

EAC-CPF (beta) |

Biography |

University of Melbourne |

|

Saulwick Polls |

Custom |

Social Science, Politics |

University of Melbourne |

|

Find and Connect Australia (8 data sets) |

Custom |

Child Welfare |

Consortium led by University of Melbourne |

|

Australian Women's Register |

EAC-CPF |

Women |

Consortium led by University of Melbourne |

|

eMelbourne: the Encyclopedia of Melbourne |

Custom |

Melbourne |

Consortium led by University of Melbourne |

|

eGold: Electronic Encyclopedia of Gold in Australia |

Custom |

Gold Mining |

Consortium led by University of Melbourne |

|

Wallaby Club |

Custom |

History |

University of Melbourne |

|

Obituaries Australia |

Custom |

Biography |

Australian National University |

|

Circus Oz Living Archive Video Collection |

Custom |

Circus |

RMIT University |

|

Australian Film Institute Research Collection |

Custom |

Film |

RMIT University |

Setting up the HuNI harvesting process has required development iterations across two levels of technology deployment. The first relates to the technology needed for data providers at the partner sites to publish their data in XML (eXtensible Markup Language) format. HuNI provides three options for supplying data: jOAI [http://www.dlese.org/dds/services/joai_software.jsp] and OAIcat for those who are exposing their data via OAI-PMH (Open Archives Initiative – Protocol for Metadata Harvesting) and a custom-built non-OAI solution that requires little work to integrate at a provider's site. The second aspect of the deployment relates to technology for harvesting updated content from the partner XML data feeds and transforming the data into forms suitable for ingestion into a Solr search server.

Each data set was evaluated against a set of criteria to determine its readiness for ingest:

- the capacity of the data source to connect to the HuNI ingest system (i.e., its communication protocols and technical infrastructure);

- its capacity to expose and export data in OAI-PMH;

- the availability and extent of documentation of the data models used to develop and maintain the data set;

- the extent to which the data provider adheres to or uses standard schemas or information standards in its data structures and technical infrastructure;

- the availability of technical and data modelling advice and support from the data provider;

- the readiness of the data provider for engagement with the HuNI Project Team, their availability for liaison, and problem resolution;

- the data provider's capacity for supporting data analysis and mapping; and

- the alignment of the data with the core entities in the HuNI data model.

The integration of partner XML records into the HuNI data aggregate depended on successfully mapping them to a core HuNI data model. Defining this core model has been an iterative process that involved testing several different approaches. A range of cultural heritage ontologies was initially examined as a starting-point for building a core ontology framework.4 These included CIDOC-CRM (Comité International pour la Documentation – Conceptual Reference Model), FOAF (Friend of a Friend), PROV-O (Provenance Ontology), and FRBR-OO (Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records – Object Oriented). However, significant technical and conceptual difficulties became clear with this approach. In part, these challenges arise from broad disciplinary shifts within the humanities, away from a traditional focus on measuring the value and meaning of cultural artefacts to recognizing the import of cultural flows and the dynamic nature of cultural infrastructure (itself understood as a creative process and catalyst of social and environmental amenity).

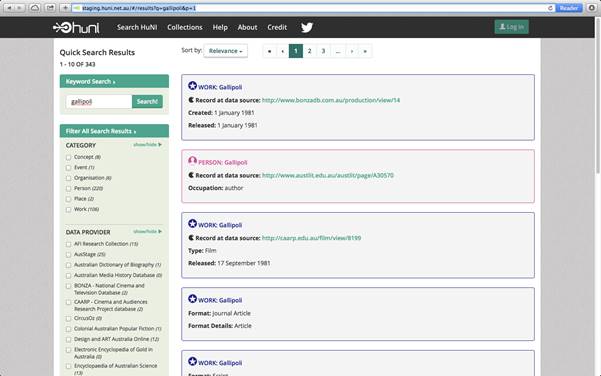

The alternative approach adopted by HuNI maps the incoming harvested XML records to a data model [http://wiki.huni.net.au/display/DS/Data+Model] consisting of six core entities: Person, Organization, Event, Work, Place, and Concept (see figure 2). This data model was derived from a rigorous analysis of the entities present in the source data sets. As of April 2014, HuNI contained the following entities:

- Concept (5,218)

- Event (9,092)

- Organization (42,466)

- Person (260,688)

- Place (680)

- Work (297,533)

Figure 2. HuNI search screen

Deploying Tools

The HuNI virtual laboratory is designed to support the nonlinear and recursive research methods practiced in the humanities. HuNI provides discovery tools for casual users from the wider community, but more sophisticated functionality is available to researchers who register for an account in the virtual laboratory. Registered researchers have their own personal workspace within HuNI. Central to the design of the HuNI platform is the recognition that HuNI users will already be comfortable with existing tools and workflows. Consequently, researchers can authenticate themselves using social media logins and will also be able to share their discoveries and activities through their existing social media accounts.

Any researcher with a HuNI account can work with the HuNI data aggregate in a personalized way through a "My HuNI" interface. The following functionality will be available to researchers with HuNI accounts:

- Run a simple search across the aggregated data and browse the search results by facets based on the core entities

- Conduct an advanced search across the aggregated data records

- Save their search results as a private collection

- Refine or expand a collection through additional searches of the HuNI data aggregate

- Annotate entities within the HuNI data aggregate with assertions about the links and relationships between them (producing "socially-linked" data)

- Analyze and annotate collections with their own assertions, interpretations, and commentary

- Export collections into other digital environments for further analysis

- Publish collections (search results and annotations) for use by other researchers

- Share collections and annotations through social media (such as Twitter, Facebook, GooglePlus, and LinkedIn)

An existing external software tool Heurist (developed and maintained at the University of Sydney) is also being augmented to interface with HuNI.

Heurist is developing database-on-demand services for HuNI that will contribute data to the aggregate. Researchers will be able to set up a database in Heurist and then publish this database to HuNI. Heurist will serve as an exemplar of a "HuNI-compliant" database creation tool, as well as a future data source provider.

User-Centered Design

A user-centered approach to the development of the virtual laboratory has been deployed, with the aim of ensuring that its functionality and user interface design align with researchers' needs and expectations. This approach is essential to ensure that the virtual laboratory is adopted, used, and supported by the research communities it is designed to serve. The Agile software development framework has been used to manage the technical development in order to ensure it aligns closely with the expectations of the "product owner."

A set of 21 user stories were identified from interviews with researchers who expressed an interest in using the HuNI virtual laboratory. These stories covered a range of different disciplines and include topics like "Cultural flows of cinemas," "Mapping narrative locations," "Australian video art history," and "Rock art research." Each story was mapped to 20 high-level functions, ranging from "Browse, find, and display" to "Visualize" and "Publish data set."

A requirements analysis document was derived from an analysis of the 21 stories. For each user story, it contained

- a general analysis of the story,

- requirements for the HuNI data model (covering entities, relationships and attributes), and

- a number of small Agile user stories (expressed as functional requirements or features for the system).

The Agile stories from all 21 cases were then compiled into a single "product backlog" and prioritized for implementation by the solution architect and technical staff. One limitation of this process has been the lack of existing cultural data aggregates, which has meant that the proposed user stories do not necessarily address the potential of HuNI for interdisciplinary research enquiries.

With this in mind, HuNI has sought the guidance of an expert data group, which brings together a representative group of HuNI early adopters and data custodians, and an international expert advisory group. The initial prototype of the virtual laboratory has been demonstrated and tested in a series of conference presentations and user workshops. Exposing researchers to an early HuNI prototype on the other hand has provided an opportunity for likely users to communicate their expectations and the perceived benefits that HuNI offers. These included HuNI's capacity to provide new, online opportunities for "serendipitous discoveries through identifying points of commonality between data" and to "cross-search a significant amount of data in a single software environment and see networks of relationships" (anonymous user feedback). A revised version of HuNI with greater functionality is currently being finalized and will be available for user testing during May and June 2014.

Conclusion

The HuNI virtual laboratory is integrating humanities data at a national level and deploying capabilities that enable researchers to work with the aggregated data. A number of significant challenges are being addressed as part of this process:

- Integrating a variety of heterogeneous data sources

- Defining a core data model for integrating these sources

- Overcoming inconsistencies in the source data

- Building a centrally aggregated HuNI platform, rather than using a distributed or federated approach

- Scheduling and managing the complex process of data ingest, alignment, and matching from the data sources

- Defining and building the core functionality for researchers to work with the aggregated data

- Ensuring an appropriate level of input from users into the iterative design of the virtual laboratory

- Anticipating interdisciplinary user requirements, workflows, and expectations when these do not yet exist

By demonstrating and testing an innovative new model for the design of humanities e-research infrastructure, HuNI is enabling larger-scale research questions to be pursued more effectively. It is also increasing the effectiveness of researchers' use of cultural collections and working to ensure that research results are fed back into the management of these collections. HuNI expects to deliver the following benefits:

- Humanities researchers can work with cultural data sets on a larger scale than previously possible.

- The systematic sharing of research data among humanities researchers is being encouraged and enabled.

- A higher level of cross-disciplinary and interdisciplinary research is being supported and promoted.

- Innovative research methodologies, which rely on large-scale data sets, are being enabled.

Through its use and development of innovative technologies and techniques, the HuNI project proposes some large questions, far beyond the specific queries of participating researchers: how might the opportunities presented by an unprecedented proliferation of networked data also challenge the unspoken assumptions and ordinary practices of conventional humanities research? Underlying the HuNI initiative is the recognition that cultural data is not economically, culturally, or socially insular, and, in order to explore its dimensions fully, researchers need to collaborate across disciplines, institutions, and social locations.5 If we understand humanities research problems as comprising interdependent networks of institutional, social, and commercial practices, then it follows that new kinds of "evidence" and new ways of organizing, accessing, and presenting this evidence are critical for our enquiries.

- T. Burrows, "Sharing humanities data for e-research: conceptual and technical issues," in Sustainable Data from Digital Research, N. Thieberger, ed., PARADISEC, Melbourne, 2011, pp. 177–192.

- K. Kilner, "AustLit: creating a collaborative research space for Australian literary studies," in Resourceful Reading: The New Empiricism, eResearch and Australian Literary Culture, K. Bode and R. Dixon, eds. (Sydney: Sydney University Press, 2009), pp. 299–315.

- J. Bollen, N. Harvey, J. Holledge, and G. McGillivray, "AusStage: e-research in the performing arts," Australasian Drama Studies, vol. 54 (2009), pp. 178–194.

- E. Hyvönen, Publishing and Using Cultural Heritage Linked Data on the Semantic Web (San Rafael, CA: Morgan and Claypool, 2012).

- D. Verhoeven, "New Cinema History and the Computational Turn," in Beyond Art, Beyond Humanities, Beyond Technology: A New Creativity: World Congress of Communication and the Arts Conference Proceedings (Minho, Portugal: University of Minho, 2012).

© 2014 Toby Burrows and Deb Verhoeven. The text of this EDUCAUSE Review online article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license.