Key Takeaways

- Given the importance of digital content to scholarship, institutions are increasingly developing strategic digitization programs to provide online access to both their reference collections and their unique and distinct materials.

- The internal digitization program at the National Library of Wales focuses on its collections and supports many projects, offering access to over 2,000,000 pages of historic Welsh newspapers, journals, and archives.

- Work on the program has yielded theoretical as well as practical results; among the former are the definition of five categories of digital content engagement: use it, share it, engage with it, enrich it, and sustain it.

- Using these categories as a guide can help ensure that programs add to their digital content's value, increase its impact, and ensure its maintenance as part of a shared digital research infrastructure.

Lorna Hughes is University of Wales Chair in Digital Collections, National Library of Wales.

Researchers in the arts and humanities today take for granted a wealth of digital content as the basis for their scholarship. The use of digital collections — primary sources that have been digitized; online reference resources, including catalogues and scholarly journals; and born-digital material from publishers — is now a critical part of the scholarly life cycle, as is the underlying digital infrastructure that delivers this content to the widest possible audience.

This dependency on digital content makes us all digital scholars in one way or another. A recent Research Information Network report, Reinventing Research? Information Practices in the Humanities [http://www.rin.ac.uk/our-work/using-and-accessing-information-resources/information-use-case-studies-humanities], noted that all scholars surveyed for the report "access journals through their library's databases, most frequently mentioning JSTOR."1 As our development of digital collections reaches maturity, an understanding is emerging that our digital content is in many respects a living entity — one that is constantly shifting and being repurposed and reused. It is also fragile and must be sustained to remain usable.

Digital content is often created through initiatives in education, government, and cultural heritage organizations. Although early initiatives — especially those funded by the New Opportunities Fund (NOF), a British National Lottery program that ran until 2005, or the UK's Arts and Humanities Research Council's Resource Enhancement Scheme (from 2000–2008) — were typically specific, "boutique" projects aimed at creating access to thematic or specialized content, funding agencies subsequently developed more strategic programs. These include the UK's Joint Information Systems Committee (JISC) Content and Digitisation Programme, which aims to "build a critical mass of content," "help meet teaching needs," and provide better access to fragmented or inaccessible primary sources. Similarly, international digitization initiatives, funded by the likes of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, were based around a "mass digitization" paradigm, focusing on digitizing whole collections or general interest content such as journals (including, of course, JSTOR).

Similarly, libraries, archives, and museums have developed strategic digitization programs to provide online access to reference collections, as well as to unique and distinct materials. This article describes one such program: The National Library of Wales (NLW) internal digitization program. In addition to describing the activities of this program, the discussion here poses some questions about the longer-term use and impact of our digital heritage.

The National Library of Wales Program

NLW's digitization program was initially based around its print collections. One of its first efforts was the Welsh Journals Online/Cylchgronau Cymru project. Funded by JISC and the Welsh Government, the project offers access to 400,000 pages of text in both Welsh and English from a selection of 19th, 20th, and 21st century Welsh and Wales-related journals and periodicals held at NLW and partner institutions.

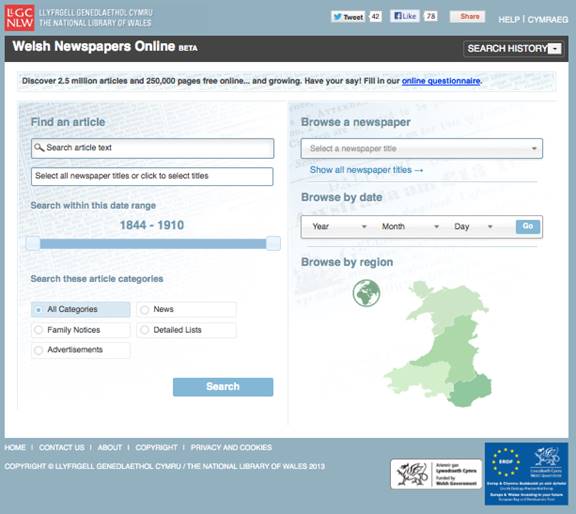

Following the journals project, the library began a more ambitious project, Welsh Newspapers Online, which will deliver more than two million pages of 19th century Welsh newspapers in Welsh and English.2 Following the success of these projects, the library began a collaborative project to digitize the archives of Wales that relate to the First World War in Wales, The Welsh Experience of the First World War. Underpinning all NLW digitization is the underlying principle that the library's online content should be freely available as part of a "National Digital Library of Wales" (see The Digital Fabric of Scotland: The Challenge of Stitching It Together).

Figure 1. Home page of the Welsh Newspapers Online project

In 2011, the NLW established a Research Programme in Digital Collections and created my post as a research chair in digital collections funded by the University of Wales. The program currently has two staff members, four PhD students, and a range of collaborative projects with partner organizations around the world. Part of the impetus for establishing this program was the desire to create sustainable digital projects. However, sustainability is not defined purely in terms of digital curation and preservation, but also as something that should be investigated from the other end of the digital life cycle through a qualitative and quantitative analysis of the use and users of the library's digital content.

The program's research focus has two thematic aspects:

- Developing an understanding of how our existing digital content is used, and using this knowledge to identify ways to enhance the content and make it more valuable for use in research, teaching, and community engagement

- Building projects that develop new digital content that addresses specific research or education needs in partnership with academics and other key stakeholders

This research addresses all aspects of the convergent practices embedded in digital collection use across disciplines and communities.

Five Categories

I frequently characterize the NLW research as "what do people do with all this digital stuff?" To date, the NLW program's conclusions on this question are that there are five categories of engagement with digital content — use it, share it, engage with it, enrich it, and sustain it — and, as I now describe, these categories add to digital content's value, increase its impact, and ensure that it is maintained as part of a shared digital research infrastructure.

Using Digital Content

Digital content use is creating new paradigms of teaching and research that let scholars carry out traditional research (searching, collating, and comparing) far more effectively. Such content can also create a transformation of scholarship, through research that would otherwise be impossible or that addresses research questions that could not be resolved without digital approaches.

There is a formula for this new approach to scholarship. First, we must bring together digital content — that is, the collections that have been developed so lovingly, so expensively by memory institutions and universities over time. For digital content to be useful, it must be of the best quality: digitized to the highest standard, described using the most detailed metadata possible, and presented in ways that enable its use by audiences for diverse purposes, some of which will be unforeseen. And, dare I say, for humanities data to truly serve research, digital content must be free.

Second, we must understand and use research methods that the digital sphere enables — the "scholarly primitives" that allow researchers to gain new knowledge: discovering, annotating, comparing, referring, sampling, illustrating, and representing digital content. Digital methods should be precise, rigorous, and replicable.

Third, we must acquire appropriate tools: the software to gather, analyze, and process data — which enables hypothesis testing and data interrogation — as well as to represent and publish the data.

Together, these aspects enable the type of scholarship that demonstrates a digital collection's value. They also demonstrate another key aspect of digital scholarship: it involves extended communities of practice and many stakeholder groups, including researchers across the arts and humanities and scientific disciplines, librarians, archivists, the public, family historians, cultural heritage staff, funders, technical experts, and data scientists.

This integration of content, tools, and methods can be seen in the work produced by the PhD students based in the NLW digital collections research program, which works in partnership with other universities. All four of our students focus on digital collections and digital humanities research methods in their work:

- Lloyd Roderick [http://widah.wordpress.com/2013/03/06/digital-paint/] (Aberystwyth University) is working on "Kyffin Williams Online," a project that presents and interprets traditional art in new contexts.

- Andrew Cusworth http://widah.wordpress.com/2013/03/05/echoes-traces-a-digital-approach-to-welsh-traditional-music/] (Open University) is researching traditional Welsh music in terms of both performance and how its reception informs cultural history.

- Rhian James [http://widah.wordpress.com/2013/03/22/wills-and-digital-ways/] (University of Wales) is investigating digital humanities and the representation of Welsh wills online.

- Calista Williams [http://widah.wordpress.com/2014/05/23/libraries-and-national-identity-in-wales-1880-1916/] is using historical network analysis to investigate the establishment of the National Library of Wales.

Sharing Digital Content

Various issues lock our digital content in silos, preventing its use; the easiest way to overcome these issues is to share data with the widest possible audience through harvesting and aggregation. NLW uses APIs to share its digital content with many partner aggregator organizations. Our resources are accessible from outside the library's own systems through merged catalogues and aggregation services. Working with partners such as The European Library and Europeana ensures our content is set in new international contexts, where it can frame research questions. This also exposes Welsh language, ideas, and history to the widest international audience alongside other external content, allowing for the widest recognition of NLW resources.

Linking Digital Content

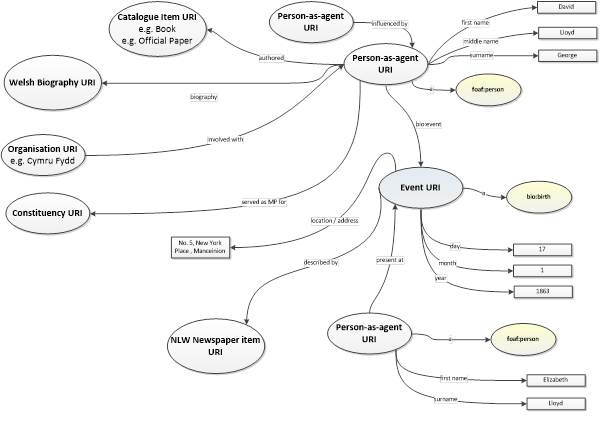

Much digital content that is currently "locked" in silos would benefit from integration with other freely available content. To address this, we are exploring how to integrate content using linked data approaches in collaboration with the Dictionary of Welsh Biography (DWB), which was developed by the University of Wales and is sustained by the library. The DWB has been marked up according to the Text Encoding Initiative's guidelines and is thus richly encoded content with the potential to become a backbone to many other collections and resources.

The data is very consistent, with encoding for entities including names, dates, and places. This can be structured as triples: subject-predicate-object expressions that define the qualities or elements of an entity that is given a Uniform Resource Identifier (URI), which makes it permanently identifiable over the web. In practical terms, this data can be linked to different sources, such as newspaper articles, works of art, and other historical sources. This encoding also supports the visualization of key data, such as dates, places, relationships, or influences.

Figure 2. A data model for the Welsh biography online data

Engage with It: Digital Collections and Citizen Science

Digital content is not static. It can be enriched by external users and transformed for re-use. NLW has explored the use of community-generated content for several purposes. Our first "citizen science" project, Wales1900 [http://www.cymru1900wales.org/], used crowdsourcing methods — that is, the idea that the capability of the crowd's collective intelligence, collaboration, and knowledge aggregation is greater than that of the individual. Wales1900 invited volunteers to transcribe Welsh place names in digitized, geo-located 19th century Ordinance Survey maps. These six-inch maps contain a definitive list of place names at a fixed point in time and preserve many historic names that are now lost. Compiling an accurate, definitive list of Welsh place names is a project that would take many years using traditional data-gathering approaches.

In addition to its efficiency, Wales1900 taps into local knowledge and memory, gathering stories about a place's origin and variant names and identifying map errors. The project's output will be a comprehensive, geo-referenced gazetteer of 19th century place names. This data will provide an important piece of the digital research infrastructure for Wales and provide a reference resource to enrich the country's other digital collections, including Welsh Newspapers Online.

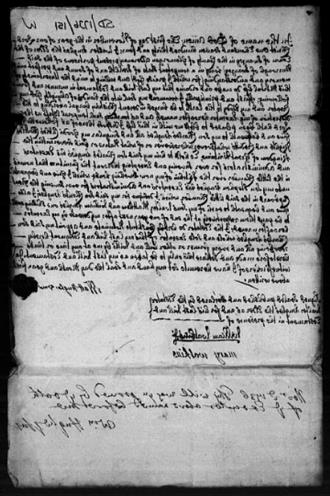

We are building on the Wales1900 project to explore a more in-depth engagement with our existing user communities. Our plan is to invite them to contribute a specific type of content: transcriptions of an online collection of scanned Welsh Wills from 1600–1850. We have developed a targeted crowd-sourcing project, aimed at specific communities — students, historians, archivists, retired archivists, and others interested in the topic. We'll gather the transcriptions in a twofold process. First, we'll obtain existing transcriptions from family historians and students. Second, we'll investigate ways to invite people to contribute new transcriptions of wills from this period in a managed and mentored way.

In this project, the biggest benefit might not be a vast number of transcribed documents, but rather the transformation of people's experience of immersive interaction with digital library collections and a public that is encouraged to collaborate in producing new knowledge. Enriching digital content in this way can enable greater engagement with primary sources than was previously possible, democratizing the research process and encouraging better engagement with our audiences.

Figure 3. A 17th century Welsh will from the National Library of Wales collection

Sustain It

"Future generations of scholarship in the arts and humanities will depend upon the accessibility of a vast array of digital resources in digital form becoming more widespread."3

The need to sustain our digital content — and the research it enables — is something we must not underestimate. In response to concerns about survival of our personal and national digital histories, NLW is developing a strategy for conservation and preservation of our digital heritage, placing traditional conservation practice alongside digital, and identifying necessary expertise in creating, managing, and sustaining digital content.

Conclusion: Digital Content Advocacy

Across disciplines, scholars use digital content, or at the very least, electronic resources that point to analog resources. Digital content has become a vital part of our research infrastructure, yet it is expensive to maintain and sustain and frequently developed through short term-funding initiatives with outputs that are often "silo-ized." To make the case for sustaining existing digital content and developing new digital collections, we must demonstrate their importance as a key component of the scholarly research ecosystem. The best way to advocate for this is to gather evidence that shows digital content's impact, value, and transformative effect on research, teaching, and public engagement — developing scholarship that is more than just efficient but that in fact helps formulate new research questions.

Considerable time, attention, and money have been invested on research into data creation and management, yet little research exists on digital content use. Gathering this evidence is crucial if we are to show that digital collections are an essential component of the research infrastructure. Better and more evidence-based use cases about what we do with our digital content will demonstrate how we are using, sharing, engaging, linking, enriching, and sustaining our valuable digital collections, and in turn ensure they are maintained and developed over the long term.

Acknowledgment

A longer version of this article was originally presented as a keynote at the Oxford University Digital Humanities Summer School in July 2013.

- Monica Bulger, Eric T. Meyer, Grace de la Flor, Melissa Terras, Sally Wyatt, Marina Jirotka, Katherine Eccles, and Christine Madsen, Reinventing Research? Information Practices in the Humanities, Research Information Network, 5 April 2011.

- Lorna M. Hughes, "Live and Kicking: The Impact and Sustainability of Digital Collections in the Humanities," Proceedings of the Digital Humanities Congress, 2012.

- Susan Hockey and Seamus Ross, Methods Network: Final Report, March 2008.

© 2014 Lorna Hughes. The text of this EDUCAUSE Review Online article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No derivative works 4.0 license.