Key Takeaways

- Digital modeling aims to restore the multisensory and real-time experiences of the past that we have known only through static words, approximating the words as spoken and heard at the time of the original event.

- The visually compelling, historically appropriate, and convincing virtual model of Paul's Cross produces an illusion of completeness and authenticity, obscuring the extent to which much of the model is only representationally accurate.

- Limitations to our ability to exactly replicate past events in a virtual model limit — without eliminating — our ability to extrapolate from that model to advance scholarship.

John N. Wall is a professor in the Department of English at North Carolina State University.

Multimedia modeling has begun to fulfill digital humanities' promise of providing what David Berry deemed a "new way of working with representation and mediation," enabling us "to approach culture in a radically new way."1 One aspect of this "new way" of working is the restoration of multisensory and real-time experience. Using this capability transforms our understanding of the past from the print or static word to the word spoken and heard, the word performed, the word as interchange, situated in the specifics of a particular time and place. As we begin to re-create, and therefore in some sense re-experience, cultural events as they unfolded in real time, digital modeling engages us in an approximation of the event as it occurred in the past. The Virtual Paul's Cross Project takes viewers back to experience John Donne preaching his sermon for Guy Fawkes Day on November 5, 1622. More accurately, the virtual environment allows us to experience as close an approximation as we can create of the event given the technology available today — and the limits of our knowledge.

Paul's churchyard, the cross yard, looking west. From the visual model constructed by Joshua Stephens

and rendered by Jordan Gray. Banner design by David Hill.

Developing Understanding through Virtualization

The Virtual Paul's Cross Project develops our understanding of the post-Reformation Church of England as a religious body functioning in a culture of speaking and hearing as well as writing, manuscript, and printed text.2 Funded by a grant from the Endowment for the Humanities, this project employs a team of scholars, historians, architects, actors, and acoustic engineers using both visual and acoustic digital modeling technology to re-create as fully as possible the experience of hearing John Donne preach his sermon in the churchyard of St. Paul's Cathedral in London, 1622. These digital tools, customarily used by architects and designers to anticipate the visual and acoustic properties of spaces not yet constructed, in the Virtual Paul's Cross Project re-create the visual and acoustic properties of spaces that have not existed for hundreds of years.

Paul's churchyard, looking east, from the west. From the visual model constructed by

Joshua Stephens and rendered by Jordan Gray.

The Virtual Paul's Cross Project re-creates as accurately as the evidence allows the participants' experience in the northeast corner of Paul's churchyard. Digital modeling technology enabled us to integrate the physical traces of St. Paul's Cathedral from before the Great Fire of London in 1666 — measurements of the foundations and study of the surviving stones — with the historic visual record of the cathedral and its surroundings, resulting in a highly accurate visual model of the cathedral and its churchyard in the 17th century. (See "The Visual Model for the Paul's Cross Project.") Our model depicts the northeast corner of Paul's churchyard, including the choir and north transept of the cathedral, the Paul's Cross preaching station, and the buildings surrounding the churchyard: chiefly mixed-use houses with retail book shops on the ground floor and living accommodations above. The model also includes the buildings on the streets that run alongside the northeast corner of the churchyard, specifically Paternoster Row to the north and the Old Change Street to the east, as well as their intersection at the west end of Cheapside.

This project lets modern viewers join the crowd gathered at Paul's Cross, the preaching station in the churchyard of St. Paul's Cathedral in London, on the morning of November 5 to hear Donne preach. Surrounded by the visual world of cathedral and its adjacent buildings, we can hear Donne's sermon performed inside the acoustic model of this space and experience it as an event unfolding in real time — observers in the interactive and collaborative occasion heard in the physical space for which Donne composed it.

Viewers can experience this event from multiple angles, hearing Donne's sermon for Gunpowder Day in its full two-hour version from two different locations in the churchyard. They can also hear portions of the sermon from eight different listening positions and in the company of four different sizes of crowd, from 500 people to 5,000 people, modeling the range of contemporary estimates of attendance at these sermons.

Opening of Donne's sermon as heard from about 50 feet east of the Preaching Station, in the company of about 500 people.

Same section of the sermon as heard from the Sermon House south of the Preaching Station, again in the company of about 500 people.

In reality, however, Donne did not deliver his sermon for Guy Fawkes Day 1622 in the Paul's Cross churchyard: The title page of the printed version tells us that the sermon, although written for that site, was actually "Preached in the Church … by reason of the weather."3 We modeled this particular Donne sermon in large part because the manuscript version, written down shortly after its delivery, represents the Paul's Cross sermon closest in transcription to his actual delivery.

Reconciling Limitations and Contradictions

In spite of our efforts to document each of the many elements that compose our models, we are very aware of the limits on our knowledge. On the one hand, the structures in the Paul's Cross visual model4 aspire to the highest possible degree of accuracy.5 We have high confidence in the accuracy of this aspect of the model.

Yet other measurements — the height of the Paul's Cross preaching station, for example — are lost to us, or come with conflicting evidence. We know, from a 19th-century survey of the foundations of the preaching station, that the base of the foundation was 34 feet across, and the base of the structure sheltering the preacher was 17 feet across.6 Yet visual images of the preaching station (such as the John Gipkin painting from 1616) show it as a relatively slim building, totally different in proportion to the numbers derived from the survey. In addition, the detailed visual depictions of St. Paul's Cathedral that survive from the early modern period are internally contradictory; the more closely one looks at them, the more discrepancies appear.

John Gipkin, painting of Paul's Cross (1616).

Image courtesy of the Bridgeman Art Library,

New York, and the Society of Antiquaries,

London.

Paul's churchyard, looking north, from the Sermon

House. From the visual model constructed by Joshua

Stephens and rendered by Jordan Gray.

Even more challenging, we have measurements of the foundations and verbal descriptions of the buildings surrounding the churchyard to the north,7 but not visual depictions of them. What one sees in this part of the model, therefore, are representative structures, based on the appearance of comparable buildings from the early modern period that survive in London or in cathedral towns in other parts of England.

What one sees on the Paul's Cross website, therefore, represents our interpretation of the evidence available and offers a range of visual approximations, from the high accuracy we believe characterizes our model of the cathedral itself, to the slightly more approximate depiction of the Paul's Cross preaching station, to the more representational visual depiction of the mixed-use buildings around the churchyard to the north and east.

Paul's churchyard, looking east, from the west. From the visual model

constructed by Joshua Stephens.

Striving for Environmental Accuracy

Unlike many digital reconstructions of historic buildings, which present everything in a pristine state, the visual model in the Virtual Paul's Cross Project shows the effects of time, climate, and season. The sermon at the heart of the model was preached outside a building already several hundred years old and in a city where a particularly acidic form of coal was burnt to provide heat for comfort and for cooking. As a result, "a seemingly perpetual cloud of sulfurous smoke [hung] over London."8 Our visual model adds evidence of this smoke to the general gloom of a mid-November day in London,9 when the weather was, more likely than not, overcast and chilly, the sun rising at 7:20 a.m., setting at 4:12 p.m., and never getting higher in the sky than 20 degrees of elevation, thus casting a long shadow even at noon.10

Paul's churchyard, looking east. From the visual model constructed by Joshua

Stephens and rendered by Jordan Gray.

The result is, we believe, visually compelling, historically appropriate, and convincing — an illusion of completeness and authenticity that obscures the extent to which much of the model is only representationally accurate. Also, could model the visual and acoustic space, but not other elements of the experience. Conveying the smell, for instance — likely to be a mix of horse manure, human sweat, and rotting garbage — has so far eluded us. Nor have we been able to incorporate the likely, although random or unpredictable, events, like a dog fight breaking out or someone collapsing among the crowd. We are modeling elements of reality, not engaging in time travel.

To use digital modeling appropriately, therefore, we need to keep both the opportunities and the limits of the practice in mind. Willard McCarty once told me11 that the digital humanities were closest to the sciences in practice when we engaged in thought experiments through modeling, all the while aware that our models — no matter how accurate and how much historical information they enfold — were simple approximations of reality, never the events, times, or places modeled.

Similar opportunities and limitations apply to the acoustic model developed for the Virtual Paul's Cross Project.12 We have very little idea how John Donne might have sounded. Yet, our not knowing everything does not mean that we know nothing.

Modeling the Acoustics

To create the acoustic model, we delivered a simplified version of our visual model, together with a list of the materials out of which the objects would have been constructed in 1622 — stone, wood, plaster, brick, dirt, and the bodies and clothing of the congregation — to acoustic engineers Benjamin Markham and Matthew Azevedo, who imported it into an auralization program. (See "The Acoustics Model for the Paul's Cross Project.") The resulting acoustic model now functions like the visual model, allowing us to gather what we know or can surmise, in this case about sounds of preaching, about the sound of spoken English, and about the ambient sounds of urban life in early modern London.

The acoustic model may well be the most consistently accurate feature of the whole project. The acoustic modelling program incorporates the absorptive, reflective, and dispersive qualities of the forms and materials in the space into the acoustic model it produces.

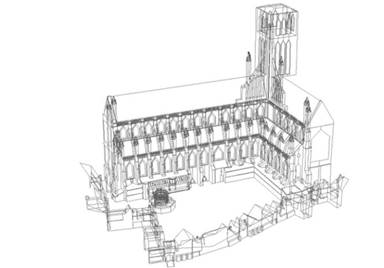

Wireframe image of the acoustic model, Paul's churchyard, the

cross yard. Wireframe from the visual model constructed by

Joshua Stephens.

Rather than try to take a full inventory of all possible kinds of ambient noise and try to assess the degree of impact for each of these sounds, we chose to represent this noise by concentrating on three sources of noise — the birds, horses, and dogs — documented as sound sources in Paul's churchyard through their appearance in Gipkin's painting, and all occurring randomly during the delivery of Donne's sermon.

Detail, painting of Paul's Cross, John Gipkin (1616). Image

courtesy of the Bridgeman Art Library, New York, and the

Society of Antiquaries, London.

Hearing Paul's Churchyard

The accompanying sound clips position the hearer in Paul's churchyard to experience the acoustic model on its own, with the sounds of ambient noise but without the sounds of the preacher. These clips locate the hearer in the middle of the space between the Paul's Cross preaching station and the north transept of the cathedral, about 30 feet from the side of the choir. Each sound clip lasts approximately one and a half minutes and provides an experience of Paul's Churchyard as a physical space.

Imagine standing in the churchyard early in the morning, before the crowd has begun to gather for the sermon. The first sound clip presents the Churchyard empty of human life, except for the rider on the horse that trots through during the course of the recording. The space is given over to the dogs, the horses, and the birds visible in John Gipkin's painting.

The second clip adds to the sounds of animal life the acoustic traces of about 250 people, essentially the number of people shown listening to a Paul's Cross sermon in Gipkin's painting.

Thanks to Tiffany Stern's recent research, we know that part of the soundscape of Paul's churchyard was the sound of a bell, activated by a clock mechanism, that rang on the quarter hours and hours each day.13 We have incorporated this sound into the acoustic model, yet this, too, is at best an approximation: Stern also noted the existence of more than a hundred parish churches in the City of London in the 1620s, with clocks that rang out the hours (but not the quarter hours) and no guarantees that any of these clocks rang in coordination.14

The most important sound on the Virtual Paul's Cross website is of course the sound of the preacher's voice, created by actor Ben Crystal. Taking stock of what we do know, and applying the principles of approximation we used to develop the visual model, we can surmise a great deal about the sound of Donne's voice. Even with the limited knowledge we have, we can still use this project to explore questions about style of delivery, the congregation's response to different kinds of passages in the sermon, and the preacher's use of timing in making his points.

Donne's preaching took place within the context of a tradition of practice, informed by manuals of oratory, that define the preacher's social and professional role in relationship to other roles played by members of his congregation. Actor Crystal uses a distinctive accent in his performance, based on a script of Donne's sermon that incorporates early modern London pronunciation prepared by linguist David Crystal. Our decision to use an original pronunciation script was prompted by the fact that Donne was a Londoner by birth. In addition, Crystal delivered his performance after considering two kinds of information about this project, the first having to do with general principles of delivery with special regard for audibility in large reverberant spaces and the second having to do with what we do know about Donne's preaching style.

Detail, painting of Paul's Cross, John

Gipkin (1616). Image courtesy of the

Bridgeman Art Library, New York, and

the Society of Antiquaries, London.

Studying Assumptions

This project makes available for study our assumptions about the conditions of sermon delivery and reception in the 17th century, reminding us that these sermons were, originally, performances during which preacher and congregation interacted to shape their mutual experience of the occasion and of the sermon itself. We can now test the consequences of our assumptions as realized in the visual model and played out in the acoustic model, always aware that we can revise the model as we develop our understanding, incorporating new research into an unfolding process of development.

We have, in fact, begun to reach conclusions about the events of November 5, 1622, through the Virtual Paul's Cross Project. Based on our experience with the acoustic model, we now know that Donne's congregation could have heard him from any place in the Paul's Cross churchyard because that space acted as a kind of natural amplification system, extending the audibility of the speaker through evoking and directing ambient reverberation. We also know that Donne would have had to cope with the challenge of bells interrupting his sermon delivery, especially at 11:00 am, when the bell at St. Paul's tolling the hour would have been joined by the bells of dozens of other neighboring churches. We have begun to speculate about how he might have recaptured his listeners' attention after this interruption of well over a minute. We also have a much clearer understanding as to how Donne's sermon would have been staged, with a verger leading Donne out to the Paul's Cross preaching station in a formal procession to begin the event and leading him away when the sermon was over.

The most important development, however, is a fundamental reconsideration of the nature of the subject. The early modern sermon, traditionally construed, comes to us as a text, a composition of words on the page of a printed book or written out on the page of a manuscript. We speak confidently of what the preacher said, and quote from these texts. Sermons from the past are therefore regarded much like theological essays: experienced in private, in the quiet, air-conditioned comfort of our offices, or perhaps in the hushed surroundings of a research library. Now we recognize that those texts are at best reconstructions of the content of oral performances delivered in an interactive environment, improvised from notes, on specific occasions in chill, drafty church buildings, or, as in the case of Paul's Cross sermons, outdoors in the weather.15 As a result of this project's recovery of the real-time experience of hearing one such sermon, our understanding of these sermons, their content recorded in texts, becomes a set of traces of their performance (among other traces) — pointers to the early modern sermon but not co-equal to it.

Our multimedia model therefore integrates into one experiential presentation all the information we have today and all we might reasonably infer about the place, the space, and the physical circumstances of a Paul's Cross sermon into a single experiential and interactive model, enabling us to reach conclusions based on our experience with that model rather than on our experience of the text alone. The Paul's Cross model has thus come to mediate between the historical record and the conclusions we reach based on our virtual experience, moving us into an area in which our conclusions have no direct historical evidence to support them.

As uneasy as our approximations in the Virtual Paul's Cross Project make us regarding our conclusions, they also enable us to see and hear the most accurate re-creation of Donne's sermon possible with our current knowledge and the technology available. Keeping in mind the limitations of the model — it models but does not reproduce reality — and updating it as new research and technology become available makes the Virtual Paul's Cross a useful tool for exploring our assumptions about an important historical event. Similar virtual models could support other research projects by providing a near-real experience based on existing knowledge and allow exploration of an approximated but still representative environment.

- David M. Berry, ed., Understanding Digital Humanities (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), 2.

- For a more detailed account of the conceptualization of the Virtual Paul's Cross Project, see John N. Wall, "Virtual Paul's Cross: The Experience of Public Preaching after the Reformation," in Paul's Cross and the Culture of Persuasion in England, 1520–1640, ed. Torrance Kirby and P. G. Stanwood (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 2014), 61–92.

- John Donne, "Sermon for November 5, 1622," in Sermons, Evelyn M. Simpson and George R. Potter, eds. (10 volumes, 1953–1962), vol. IV, 235.

- Constructed by Joshua Stephens and rendered by Jordan Gray while students in the graduate program of the College of Design at NC State University, under the supervision of associate professor of architecture David Hill.

- For a fuller account of the construction of the visual and acoustic models that constitute the Virtual Paul's Cross Project, see "Recovering Lost Acoustic Spaces: St. Paul's Cathedral and Paul's Churchyard in 1622," in Digital Studies/Le Champ Numérique (Proceedings of the SDH-SEMI 2012 Conference).

- Francis Penrose, "On the Recent Discoveries of Portions of Old St Paul's Cathedral," Archaeologica, vol. 47 (1883): 381–92.

- From a survey of these structures made after the Great Fire in 1666 to secure a record of property lines; see Peter Blayney, The Bookshops in Paul's Cross Churchyard (London: Bibliographical Society, 1990) for more information and a summary of the results of this survey. The surveyors' accounts also include some details of these structures, including the number of stories and the number of gables.

- Ken Hiltner, "Renaissance Literature and Our Contemporary Attitude toward Global Warming," Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and the Environment, vol. 16 (2009): 442.

- London in 1622 was still using the Julian Calendar, hence November 5 of that year was November 10 on the Gregorian calendar.

- Our source for meteorological data is the website weatherspark.com. Unlike many visual models of historic sites, therefore, our model incorporates traces of the effects of time and weather, and shows the relative ages of the buildings it displays.

- In a private conversation at the National Humanities Center, Research Triangle Park, NC, 2014.

- The acoustic model is the work of Ben Markham and Matt Azevedo, acoustic engineers at Acentech, Inc. in Cambridge, MA.

- Tiffany Stern, "'Observe the Sawcinesse of the Jackes': Clock Jacks and the Complexity of Time in Early Modern England," paper presented at Convention of the Modern Language Association, Seattle, Washington, January 5–8, 2012. English cathedrals in the sixteenth century are known to have had mechanical clocks that recorded time by striking bells. One of these survives at Salisbury Cathedral; see Michael Maltin and Christian Dannemann, "Dating the Salisbury cathedral clock [http://clocknet.org.uk/wiki/doku.php?id=dating_salisbury]," ClockNet UK (2013). The clock at Salisbury had no face; the ringing of a bell was its sole means of communicating the time. The sounding of this clock/bell was not discretionary: it could not be stopped and started again without disrupting its accuracy as a timepiece.

- For a discussion of how Donne as a preacher might have responded to these every-fifteen-minute interruptions, see the discussion on the Virtual Paul's Cross website.

- Paul's Cross sermons survive from every month of the year, so the change of seasons did not deter their attendees.

© 2014 John N. Wall. The text of this EDUCAUSE Review online article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 license.