Key Takeaways

- Realizing the full potential of learning technologies provides instructors with tools to advance students' critical thinking skills, engage them with the knowledge life cycle, and help them acquire practical presentation skills.

- Students adapted quite readily to the blended-learning approach adopted in the library instruction course at the University of Michigan.

- Assessment of the course demonstrated comparable learning outcomes for both in-person and blended-learning library research courses.

Librarians at the University of Michigan partnered with the College of Literature, Science, and the Arts (LS&A) in 2005 to develop and deliver its own one-credit research course geared toward first- and second-year students. From the beginning, this course aimed to establish a learning partnership between students and instructors and to present concepts appropriate for undergraduate cognitive development. Our success with the course prompted us to ask questions such as, How could we reach more students? And more importantly, how do we enhance student engagement and improve learning outcomes? In pursuing answers to these questions, we found that engagement with online learning plays a significant role in defining our digital education strategy.

Increasingly, learning and knowledge creation happen outside of the classroom, most often where ideas and discussion can flow and change without the traditional classroom's constraints. How do we reimagine where, when, and how learning takes place? We offer our experience with designing a blended-learning approach to our course as part of the current dialogue about how the process of learning is changing within higher education.

The Research Course and Scalability

Library instruction at the University of Michigan has traditionally been integrated into for-credit courses and offered in single-session workshops. Spurred by the limitations of this approach, the library was eager to transform its approach to instruction. To do this well, instructors had to expand scope, scale, and flexibility in order to meet learning goals for a large and diverse population without compromising the best features of the existing program.

Because the library does not have credit-granting authority, we looked for partners to offer our course. A campus-wide library presentation on academic integrity that caught the attention of the assistant dean of undergraduate education in LS&A began a conversation between the library and LS&A about ways to improve the overall quality of undergraduate research throughout campus.

Shared acknowledgment of the need for modeling higher-level thinking resulted in the development of a semester-long for-credit course in which the library plays a more systematic role in the research process. Three librarians worked with LS&A administrators to determine where such a course would fit within the undergraduate curriculum. Once it was determined this course would best serve the needs of first- and second-year students, librarians created a curriculum and shepherded it through the curriculum approval process.

The newly created course was first offered in the fall of 2005; Michigan now routinely offers a one-credit course (UC 174) developed by the library and offered to students through LS&A. This course is offered in weekly two-hour sessions over seven weeks. It has consistently taught the information cycle, basics of the catalog, general database searching, bibliographic management software, academic integrity, effective Internet searching, and how to evaluate information (see table 1).

Table 1. UC 174 Standardized Curriculum

| Session 1 | Information Cycle; Improving Study Habits; Exploring the Library Web Site |

| Session 2 | Library Catalog; Discovery Tools vs. Keyword Control; Topic Brainstorming & Refining Topics; Primary & Secondary Resources; Scholarly & Popular Resources |

| Session 3 | Web Searching: Google & Google Scholar; Databases: ProQuest Research Library & Academic OneFile; Finding Disciplinary Databases; Evaluating Information |

| Session 4 | Citation Styles: MLA, APA, & JAMA ; Academic Integrity; Web of Knowledge & Citation Searching |

| Session 5 | Social Sciences Databases; Managing References & Creating Bibliographies with RefWorks |

| Session 6 | Natural Sciences Databases; Humanities Databases |

| Session 7 | Information for Careers; Researching Graduate Programs; Using Images from the Web; Course Evaluations |

The primary emphasis of the course is to encourage student development of critical thinking skills versus the mechanics of finding known items. Assignments have evolved over time to stress the importance of metacognitive strategies when navigating and utilizing information resources.

Enrollment in the course has steadily increased each year since it was initially offered in 2005. Recognizing the importance of students sharing with each other the value of the course, a short video was created and first shown during the 2009 summer orientation for incoming first-year students. The number of sections offered was then expanded to four for the fall term and two for the winter term starting in 2010. While outcomes have been positive, the issue of scaling remains. How do we reach more than 150 students a year? How do we incorporate the successes of our online learning models to enhance our residential student experience?

This video (4:03 minutes) introduces UC 174: Mini Course in Digital Research.

Blended-Learning Pilot

Exploring an online component was an effort to improve the overall experience for students and to examine how to scale the course to accommodate more students and transcend physical space limits. Transferring a significant portion of the course material to the web made sense insofar as asynchronous learning appeals to many undergraduates for the control it gives them over their schedules. Additionally, it felt important to engage students in their online environments, where more holistic moments of information retrieval, evaluation, and use occur. However, before investing the time and effort needed to create a completely online course, the library piloted a blended approach with three of the seven weekly sessions offered online (see figure 1).

Figure 1. Example of online module for UC 174, week 6

Developing a blended-learning curriculum for this course took a group of six librarians, both former and current instructors of the course, three months of weekly meetings typically lasting 1.5 hours to 2 hours. Meetings focused mostly on identifying strategies for moving forward, including how and when to collaborate with others to make a hybrid course possible.

The educational technologies librarian consults with groups to help them determine which web tools best meet the curricular goals of a given project. Part of this person's job is working with software developers to help set priorities for improving functionality based on emerging trends and results from pilot projects. This librarian helped the team identify which online tools already available on campus could be used to pilot the course and continues to serve as a resource to help us navigate the technical difficulties of the course as problems arise.

The method chosen to deliver the online lessons was CTools, which is the university's local instance of the Sakai LMS. Using a courseware tool called UM Lessons, the team created linear tutorials that included embedded screencasts, online quizzes, and active learning activities (figure 2). Michigan librarians used Jing, Camtasia, or Screenflow to create the majority of screencasts in the online lessons before implementation of the blended pilot course. A full-time instructional technologist employed by the library served as a consultant in the creation of these screencasts and serves as a resource when we encounter technical difficulties.

Figure 2. Example of online learning activity in UC 174, week 6

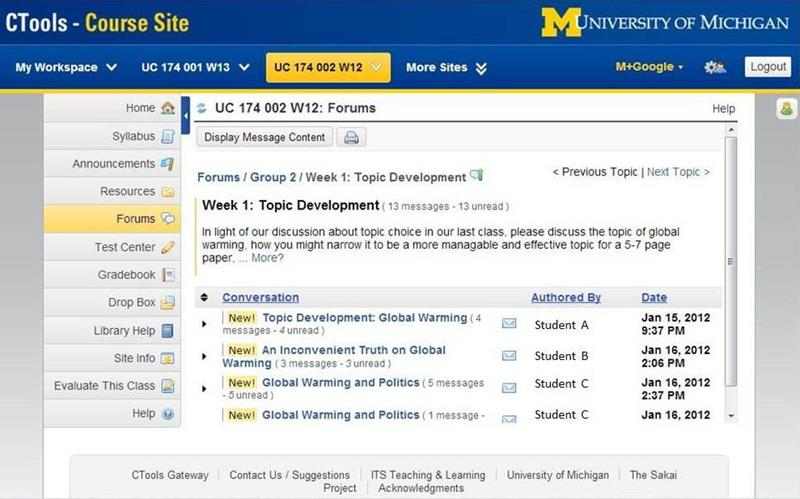

While pleased to see how quickly students adapted to using the online components in the pilot course, we continued to monitor their participation and engagement. In keeping with the literature on blended learning,1 our biggest concern with offering online modules was losing the interactive component between instructor and students and between the students themselves. The instructional technologist gave us feedback about tools to elicit student participation online and ultimately proved instrumental in designing online forums we could use to generate discussion among and feedback from the students (figure 3).

Figure 3. Example of UC 174 online forums

The instructor focused on engaging student discussion during the course using the online forums, dividing students into groups of five and facilitating collaboration by responding to several comments in each group discussion. These forums were also used as a way for the instructor to communicate about homework and other course issues without frequent e-mail announcements.

Assessment of Learning Outcomes

Data from course grades and courses evaluation were compared between the blended course pilot and the traditional sections taught in fall 2009 and fall 2010 as a way to gauge the success of the pilot course. We found that grades on the assignments, quizzes, and final course projects, as well as the pre/post-quiz assessment, were highly consistent across sections.

Students are given the pre/post-quiz assessment at the beginning and end of the course. The quiz, available to students via CTools, is worth a possible 20 points. First given in the winter 2010 term, it has been administered in each section, including the blended sections, every term since. The test measures students on information literacy skills such as identifying primary resources; recognizing if a quote has been summarized or paraphrased; understanding the parts of a citation; and effective use of the library catalog. Students demonstrated consistent improvement across sections each semester, and the scores indicate improved skills regardless of the class format (table 2).

Table 2. Pre- and Post-test Scores

| Semester |

| Section 1 | Section 2 | Section 3* | Blended-Learning Section* | Average for All Sections |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Winter 2010 | Pre-test | 11.7 | 11 |

|

| 11.35 |

|

| Post-test | 17.67 | 17 |

|

| 17.34 |

|

| Difference | 5.97 | 6 |

|

| 5.99 |

| Fall 2010 | Pre-test | 9.89 | 10 | 10 |

| 9.96 |

|

| Post-test | 15.98 | 17 | 16.6 |

| 16.52 |

|

| Difference | 6.09 | 7 | 6.6 |

| 6.56 |

| Winter 2011 | Pre-test | 14.23 | 13.54 |

|

| 13.89 |

|

| Post-test | 17.03 | 17.3 |

|

| 17.17 |

|

| Difference | 2.8 | 3.76 |

|

| 3.28 |

| Fall 2011 | Pre-test | 13 | 13 | 13.89 | 12 | 12.97 |

|

| Post-test | 15 | 15 | 16 | 15 | 15.25 |

|

| Difference | 2 | 2 | 2.11 | 3 | 2.28 |

* Section 3 and blended-learning sections were not offered every semester

The findings of related studies mimic our experience that students in the blended-learning section perform as well as students in traditional sections.2 On the course evaluation for the blended section pilot, 16 of 19 students think the blended-learning section should be offered again. One student said on the evaluation that this format "provides students with practice of self-learning and lets students set their own pace, which is a practice for future research projects."

One student's perspective on taking a blended section of UC 174 (4:47 minutes).

Three students expressed a personal preference for traditional instruction, citing the ability to ask questions in-person and feeling more motivated when there is dedicated class time. When asked about the effectiveness of the online learning modules, most students found them to be quite effective, with one student stating, "I found them very effective. My high school didn't teach me as much information about research in 4 years as I learned in half a semester." The library considers this pilot a success based on these results, and with enthusiastic support from LS&A, offered other blended-learning sections in fall and winter 2012.

Lessons Learned

The encouragement of course experimentation and resource sharing among instructors has taught us how to best develop the course and to create a practical workflow that supports the continuous transformation and innovation of our learning environments. It took us a few tries to understand, appreciate, and organize ourselves around the need to systematically provide instructors with production support as well as opportunities for pedagogical innovation. Since multiple instructors now routinely compare course syllabi and develop teaching strategies, we have come to realize the full learning potential of using a variety of teaching technologies (anonymous learning, peer-to-peer interaction, and instructor-student exchange.)

Thinking about offering a course like this at your institution? Keep in mind....

- Time: This approach requires a significant time investment upfront as well as ongoing maintenance and refreshing of content. Course development requires an ongoing commitment to ensure an engaging curriculum supported by appropriate technologies.

- Assessment: Be prepared to engage with questions such as, what are students learning? Are the tools used still effective? Are there better ways to engage students for collaboration? Is critical thinking happening?

- Resources: Identify the needed staffing and technical resources early in the process. Inventory what is already available at your institution, but be prepared to seek out or develop whatever else might be necessary.

- Commitment: Commit to making sure the course succeeds.

- Instructors: Have blended and residential instructors meet regularly and continue to inform each other's practices.

- Collaboration: Collaboration ultimately leads to success for this type of endeavor. Expect to collaborate with other librarians, with technology people, and with other units on campus who can help make your project happen.

- Marketing: Promote your course on campus and with identified stakeholders. Talk about the positive impact it will have for your students.

- The "Why": We are here to help students become critical thinkers, able evaluators and researchers, and creators of knowledge. Keep this goal in mind and you're already on your way to a successful project.

Future Plans

As we move forward, we are committed to:

- Offering the blended-learning sections on a regular basis in both fall and winter terms.

- Applying the lessons we've learned (e.g. use of technologies to promote critical thinking) from the pilot into other instructional activities.

- Exploring learning technologies that further promote the concept of blended learning as well as advance capabilities for collaboration and assessment.

- Looking for cutting-edge educational technologies that facilitate dynamic online learning and promote greater collaboration.

Instructors are exploring further options for scaling the course to an approximate enrollment of 50 students per section. The blended version allows for greater flexibility when scheduling the course and for hosting parts of it in-person. Librarians continue to work with the educational technologies librarian to identify other online technologies that could be used to manage the online modules. And, as we continue to develop the interactive pieces of the course and plan expanded offerings, we face potential limitations of continuing to use our current online courseware tool. We would also like to explore options for offering online information literacy modules in support of various departmental learning goals.

Conclusion

Our experience offers insights into the broader discourse about how the process of learning is changing. It has prompted us to further explore the relationship between pedagogy and technology, to engage with developing strategies to shift the relationship between learning goals and the tools available to create new learning opportunities, and to push boundaries about what we mean when we reference the classroom. We find ourselves at a very different place than when we started thinking about this course. We're at a place that celebrates the exploration of innovative approaches by information users and lifelong learners, and that is the goal at the heart of every academic library's mission. We find ourselves ready to engage in the next phase of course development and, more importantly, are eager to continue investing in learning environments that transform our collective approach to learning.

- Reid Bates and Samer Khasawneh, "Self-Efficacy and College Students' Perception and Use of Online Learning Systems," Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 3, no. 1 (2007), pp. 175–191; Curtis J. Bonk, Robert A. Wisher, and Ji-Yeon Lee, "Moderating Learner-Centered e-Learning: Problems and Solutions, Benefits and Implications," in Online Collaborative Learning: Theory and Practice, Tim S. Roberts, ed. (Hershey, PA: Information Science, 2004), pp. 54–85; and HamishCoates, Student Engagement in Campus-Based and Online Education (London: Routledge, 2006).

- Karen Anderson and Frances A. May, "Does the Method of Instruction Matter: Experimental Examination of Information Literacy Instruction in the Online, Blended, and Face-to-Face Classrooms," Journal of Academic Librarianship, vol. 36, no. 6 (2010), pp. 495–500; Carol Anne Germain, Trudi E. Jacobson, and Sue A. Kaczor, ʺA Comparison of the Effectiveness of Presentation Formats for Instruction: Teaching First-year Students," College and Research Libraries, vol. 61, no.1 (January 2000), pp. 65–72; and Elizabeth W. Kraemer, Shawn V. Lombardo, and Frank J. Lepkowski, "A Comparative Study of Three Information Literacy Pedagogies at Oakland University," College and Research Libraries, vol. 68, no. 4 (2007), pp. 330–342.

© 2013 Beth Strickland, Laurie Alexander, Amanda Peters, and Catherine Morse. The text of this EDUCAUSE Review Online article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs 3.0 license.