Key Takeaways

- The U.S. Air Force Academy and Colorado College, a small, private liberal arts institution, collaborated on a physics course on aircraft design with students from both institutions participating.

- The course was derived from an established USAFA aeronautics course that had integrated technology from its start decades ago; that technology evolved over time into a robust online learning environment.

- Course technologies include online videos, virtual labs, and tools that provide students with a hands-on approach to aerodynamics based on an aircraft design experience.

- At Colorado College, the course was offered using a blended learning approach and was supported by a Next Generation Learning Challenges grant administered by Bryn Mawr College.

Randall J. Stiles is associate vice president, Analytics and Institutional Research, Grinnell College. Neal D. Barlow is permanent professor and head of the Department of Aeronautics and Steven A. Brandt is a professor of Aeronautics at the United States Air Force Academy.

In November and December of 2012, the United States Air Force Academy (USAFA) and Colorado College, a small liberal arts institution, joined forces to collaborate on Physics 220: The Physics and Meaning of Flight, a freshman/sophomore level physics course on the fundamentals of flight from an aircraft design perspective that included students from both institutions.

The following case study was created through phone interviews with the course's key players:

- Neal Barlow, Head of the USAFA Department of Aeronautics and leader of the learning-focused education movement within the Department;

- Steven Brandt, Professor in the USAFA Department of Aeronautics and creator of the online learning environment; and

- Randy Stiles, at the time Special Advisor for the President at Colorado College and architect of the overall course goals, syllabus, and resources.

Origins of the Project

The seed of the joint project was planted decades ago when the USAFA's Department of Aeronautics launched Aeronautical Engineering 315Z, an introductory aeronautical engineering course taught from a design perspective and modified by Brandt to use online learning. Today, the course is a USAFA staple offered to more than 800 students each year. Although technology was relatively primitive at the outset, Brandt recognized its importance as a teaching tool and integrated 10-minute video clips, narrated PowerPoint presentations, and interactive virtual laboratory experiences into the course.

Steve Brandt: "The basic concept always was that we would create this rich learning environment that would have resources that any cadet, with any learning style, could connect with and could use to their advantage. We've surveyed our cadets — we know that there's a lot of verbal learners, a lot of visual learners, a few kinesthetic learners, et cetera. We wanted to create a learning environment that would let each of those different styles learn at their own pace on their own time."

Stiles taught the class for many years at USAFA before becoming an administrator at Colorado College, which was just 14 miles away. Once there, he began offering the aeronautics course through independent study to a few students a year; in 2003, he taught Physics 220 for the first time as a formal course with 10 students. After several other offerings, in 2013 he decided to offer the class again — this time with funding from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation to support pedagogical collaboration with the USAFA.

Randy Stiles: "It was an important initiative. The course was on the radar of the president [at Colorado College] and the dean at the academy, and was very well supported with grants as well as faculty and staff from both institutions." (More background on the course can be seen online.)

The Innovation

The Physics 220 innovation has three key dimensions:

- design concepts and tools to facilitate learning,

- collaborative work among students and faculty members from Colorado College and the USAFA, and

- a blended learning approach that draws on various Internet resources.

The course also makes connections across disciplines, from the basics in math, science, and product design to interdisciplinary connections between physics and economics, the arts, and national defense.

Design Tools and Concepts

Over the past 20 years, the course technology has evolved from PowerPoint slides to a full-fledged online learning environment. The course's tools provide students hands-on experiences with design concepts that are often taught as abstractions; watching a computer simulation of how velocity and pressure change as the student varies the size of a wind tunnel test section has a learning impact that an explanation of aeronautical principles alone can't match.

The website's launch point is an electronic course syllabus that hyperlinks to numerous resources, including virtual labs and video lessons to support students and their varied learning styles.

Brandt: "All the assignments are hot-linked into the electronic syllabus. Different resources for each of the lessons are hot-linked in as well. That lets the student who really gets the most out of watching movies watch the movies, and [for] someone who really gets the most out of playing with things, we have virtual labs where they can try out applying all these ideas."

Figure 1 shows the start page for AeroDYNAMIC with links to different resources, including the course syllabus. The Physics 220 course uses a similar page to access related materials. The aircraft photos are hot-linked to larger versions and illustrate the variety of aircraft design features accessible in this learning environment.

Figure 1. Home page accessing resources for a similar course

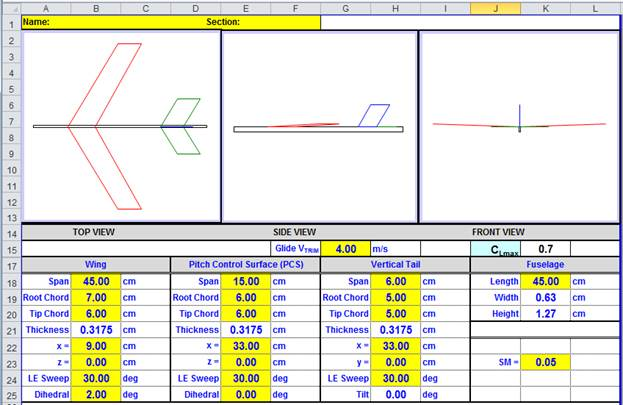

Figure 2 shows a spreadsheet used by cadets to design their balsa-wood gliders. The drawings of the glider change appropriately as students change parameters in the spreadsheet that describe the glider. Students get instant feedback on the aerodynamic performance and stability characteristics of their current glider design immediately after they change a parameter. This reinforces concepts from the course while at the same time allowing students to design gliders that fly well.

Figure 2. Spreadsheet design environment for Balsa wood gliders

As one Colorado College student noted about the glider lab, "I learned a lot more than I thought I would."

Stiles also took advantage of the technology and facilities access to run two other labs for the Physics 220 course.

Stiles: "In my course I included a wind tunnel experiment that students accomplished in groups of three. This involved a field trip to the academy, running a wind tunnel experiment with guidance from USAFA cadets, having my students record the measurements of pressure distributions over an airfoil, followed by data reduction and writing up the lab results, while benefiting from the use of technology.

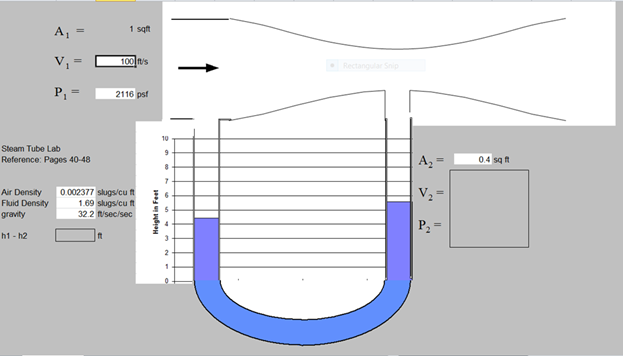

"A sophisticated spreadsheet helps them accomplish the data reduction. The third project in the course was a numerical solution of the aircraft takeoff problem-solving a differential equation using numerical methods. Student groups calculated the changing forces on an aircraft during the takeoff roll (lift, drag, thrust and rolling resistance) and then estimated takeoff distance. They were also able to explore 'what-if' scenarios involving different takeoff conditions such as altitude and runway conditions." Figure 3 shows an Excel page for a virtual lab wind tunnel exercise.

Figure 3. Virtual laboratory spreadsheet for a wind tunnel experiment

Although geographic proximity allowed students to take advantage of facilities and interactions on both campuses, Brandt designed the labs and videos in such a way that students in any type of environment can participate in the course and understand the principles at a deeper level, regardless of their access to physical resources.

Neal Barlow: "You don't have to have a lot of facilities at your school in order to accomplish the course learning objectives and accomplishing the lesson requirements; accomplishing the virtual labs, and watching the lesson videos are activities students can accomplish effectively in almost any setting."

However, having access to state-of-the-art facilities is certainly helpful — as students from Colorado College were fortunate enough to discover.

Collaborative Aspect

Simply porting the learning environment from USAFA to Colorado College and ending the collaboration there could have accomplished a great deal in terms of educating students on the principles of flight. However, an important aspect of the course was its hands-on design projects that rely on sound engineering principles — and, in two of the labs, access to a USAFA's aerodynamic lab facility and wind tunnels. The tight collaboration between the two institutions also facilitated field trips and various guest speakers.

Stiles: "The Colorado College students were able to visit Air Force Space Command Headquarters in Colorado Springs, where they were given a mission briefing by staff from the Chief Scientist's office. Also, the former president and CEO of Boeing Aircraft, Phil Condit, met with students at both institutions and shared stories about systems engineering and the economics of flight. To highlight the connection between flight and the arts, a faculty member and student in the Colorado College film studies program spoke to the class about how CC students had created a video to accompany the [Gustav Holst] symphony, The Planets. We also had the privilege of touring the archives at the Air Force Academy Library, where we saw original writings by the Wright brothers and other early pioneers of aviation.

"Near the end of the course, an astronautics professor from the academy came and gave a great talk about the orbital elements — access to space and how one monitors and controls satellite motion in space. All of these field trips were very exciting and motivating for the students."

Some quotes from the course evaluations reveal the students' enthusiasm for the field trips and guest speakers:

"As a non-physics person, I found this course extremely challenging but also the most engaging experience I have ever had in a subject. All the outings and interactive experiences such as the glider were major highlights."

"These trips showed me many of the applications of the things we were learning in class. Exploring flight in a hands-on way was definitely beneficial."

"One of my favorite aspects of this class! Very helpful in getting perspectives on the topic. I loved all the speakers."

In another project, students from both institutions explored and discussed technologies of the future. This time, the benefits were considerable for the USAFA cadets.

Barlow: "What we [at USAFA] gain is an opportunity for cadets to interact with the CC students — please excuse the terminology, but "normal" or "traditional" college students — in a conventional setting who are not thinking as a future military officer; the Colorado College students are thinking as future educated citizens and leaders of the nation. How do they think about the development of aerodynamics, and how does it apply to the future of society? As opposed to our focus, which tends to be: How does aerodynamics apply to the Air Force and the future of military operations?

"So, you've got two different groups that are thinking in different ways about how to apply the coursework that Steve and Randy are providing them, and so when these two groups get to interact, a much richer discussion between the two groups occurs. That's an advantage, I think, to both groups, and especially for the academy cadets."

As one of the participating cadets explained,

"Discussing these issues with "traditional" students gave me a greater appreciation for the broad themes of the topic. Instead of being concerned with numbers or specifics, they were interested in broad trends and principles. This changed my perspective by making me more appreciative of the general phenomenon, while at the same time making me more aware of specifics."

Blended Learning

In addition to the USAFA materials produced specifically for the course, the Colorado College class offered students access to materials from other sources such as NASA, the Khan Academy, and YouTube.

For Stiles, whose Colorado College students were on a block schedule and thus with him full-time for more than three weeks, such resources offered important resources for classroom discussions.

Stiles: "We would spend as much as an hour of the day looking at Internet-based resources that accompanied the ideas we were talking about in the class. We would collectively take certain concepts of physics and of flight in particular, and we would spend time exploring these resources. I would ask groups of the students to share their findings and to describe whether or not they found the content helpful for them. By comparing and collectively evaluating the various sources, we developed a sense of quality and helpfulness of the materials as well as those that best fit with particular learning styles."

Providing Internet access wasn't appreciated by all the students, however:

"I found that use of the Internet was very distracting. For Internet resources to be used effectively there needs to be more structure to searches and time allowed for Internet use."

Other instructors might take a totally different approach. Flexibility is especially important at the USAFA, where instructors turn over rapidly and anywhere from four to seven instructors might be teaching the aeronautics course at one time.

Brandt: "Our military instructors stay here for three or four years, and teach the core course only for the first year. Then they'll go on to teach the upper-division courses. So there's a constant changeover in instructors.

"By having this large body of learning materials always available, always the same, it helps the new instructors get up to speed. It helps them to refresh their memory of these concepts and to have a consistent body of knowledge at their fingertips. To some extent it standardizes what we're presenting. Of course, individual instructors are going to do their own thing, and they're going to use their class time the way they're comfortable with."

Lt. Col. Tom Joslyn, USAFA Dept. of Aeronautics, explains the benefits to his students and himself as a new instructor of having resources online and easily accessible (3:16 minutes).

Institutional Context

The context of the two institutions played a key role in both how the course developed over time and how offering the joint course changed the student experience.

U.S. Air Force Academy

The United States Air Force Academy (USAFA), located 15 miles north of Colorado Springs, was established April 1, 1954. The Air Force Academy is unique in its dual role as both an Air Force base and a university, with the educational organization of the superintendent, commandant, dean of faculty, and cadet wing resembling a civilian university. The academy has graduated more than 37,000 officers since its inception, with each cadet graduating with a bachelor's of science degree and a commission as a second lieutenant in the U.S. Air Force.

Colorado College

Colorado College is a small, private, and highly selective residential liberal arts college in Colorado Springs. Founded in 1874 and serving approximately 2,000 undergraduate students, the mission of the college is to provide an outstanding liberal arts education — "to develop those habits of intellect and imagination that will prepare them for learning and leadership throughout their lives."

One of Colorado College's distinctive features is its Block Plan scheduling system, which was adopted in 1970 and lets students plunge intensively into a different subject every three-and-a-half weeks rather than balancing several courses over a semester. Students take one course at a time, and professors teach one course at a time, with each block covering the same amount of material as in a semester system.

Classes are small, hands-on, and highly focused. They also permit travel: students can study the film industry on location in Hollywood or traverse the Southwest region's natural wonders as a field archaeologist. For Physics 220, this block plan let students participate in field trips that exposed them to extraordinary history and current activities in both atmospheric and space flight.

Implementation Status

Physics 220 has been taught for decades at the USAFA as a 200- or 300-level aeronautics class; it was taught as a joint class with Colorado College for the first time in 2012. The USAFA students chosen to participate in the Physics of Flight course were drawn from aeronautics majors or highly motivated students in other disciplines. Following conclusion of the course, the Physics Department end-of-course survey, answered by half of the 19 Colorado College students (15 male, 4 female; 13 freshmen, 1 sophomore, 3 juniors, 2 senior) who finished the course garnered the following results:

- "Found the subject of this course interesting": agree (22.2 percent), strongly agree (77.8 percent)

- "Course was a valuable learning experience": agree (11.1 percent), strongly agree (88.9 percent)

- "If I could give this course a grade, it would be": A (88.9 percent), B (11.1 percent)

Despite the small sample size, Stiles found the survey results encouraging — a testimonial to the value the students drew from their experiences in the collaborative blended learning Physics 220 course.

Challenges and Resolutions

In bringing the USAFA course to Colorado College, Stiles realized he needed to modify the content somewhat to suit a liberal arts environment.

Stiles: "The primary modification was just to make it more interdisciplinary. I didn't take out any of the rigor — it included the same kind of homework problems, same kind of test questions, and so on, but I tried to make it more interdisciplinary than it would have been at the [USAF] Academy.

"That's why I called it 'The Physics and Meaning of Flight' in the most recent offering, because I wanted to build on the connections of physics with economics, the arts, and national defense. For example, in studying the physics of flight, we might examine the impact of changing wing sweep on aerodynamic drag for a range of speeds. In Physics 220 at Colorado College, we often pursued the 'so what' question. In the presence of former president and CEO of Boeing Phil Condit, we were able to discuss the economic viability of a supersonic transport. By reading letters written by the Wright brothers, we acquired an understanding of how they were communicating with officials at the Smithsonian and some of the legal troubles they encountered following their pioneering work. The film that was produced to accompany The Planets illustrated how visual images of birds or aircraft in flight can complement the sound of great music."

In terms of technology, the evolution in the USAFA course was gradual; perhaps the biggest challenge along the way was in realizing the need to switch from Visual Basic to Excel.

Brandt: "As far as evolving technology, when we first created this design-oriented aerodynamics course, we worked with our Center for Educational Excellence. They created pretty much the entire package in Visual Basic. All the virtual labs were Visual Basic. All of the movies weren't, but all of the analysis and synthesis help was in Visual Basic.

"We had a grant to cover that development and to cover the expense of hiring programmers, but when it came to maintaining the software we realized it was going to be a lot more practical to move this all over to Excel and HTML.

"Basically it was, I don't know — maybe funny is the right word? We were using Visual Basic with plugins to make something that looked like Excel. We just turned it around, and we used Excel. The macros in Excel are Visual Basic anyway. So we took all these routines that we had created for the Visual Basic program and imported them into Excel as macros. It's a lot more accessible to the students. It's a lot easier to maintain. They can look and see what any equation is anywhere throughout the software."

Finally, the two institutions faced a challenge in working across institutional "boundaries" — a factor that was mitigated somewhat by their close physical proximity. However, differences in missions as well as dramatically different class schedules and time constraints for students were potential barriers.

Stiles: "In the case of Physics 220, these challenges were met due to the good will (and collaborative spirit) of faculty and administrators from both institutions. Such teamwork requires a clear recognition of the mutual benefits of collaboration and the time and energy to make those benefits a reality. The fact that I had a long history as a faculty member at the academy and personal friendships with Colonel Barlow, Dr. Brandt, and Dr. Aaron Byerley (in the USAFA Dean's Office) certainly helped make it possible to overcome obstacles along the way. It was also very helpful that the benefits of collaborative work between our two institutions had already been articulated in the application for a Mellon grant.

"After the first field trip to the academy, one of my students said: 'This is the reason I came to CC. It was really cool to get a chance to see these things (the academy Aeronautics Laboratory) that I never would have otherwise.'"

Impact of the Collaboration

The impact of the Physics 220 evolution and collaboration was both technological and interpersonal.

Barlow: "Before we had the ability to interact with our students using technology, we couldn't have accomplished a course like Steve's in the way that we do now. I think back to my early instructor days where we were still pulling up 16-millimeter films and working really hard to have all of these paper resources and film resources in order to teach a course. Those were very difficult to get out to students on an individual basis. Technology has really changed the way that we do business. I think it's better for the students. They are more engaged now than they have ever been."

Stiles: "For me, my engagement in the blended learning work funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and managed by Bryn Mawr was key. I was well aware of the great technical tools Dr. Brandt and his academy colleagues had developed over the years. When I heard about the increasing need for such resources at small, private colleges like CC as they begin to experiment with blended learning, it occurred to me that bringing together some of the great strengths of the academy (extraordinary laboratory and educational technology tools) and those of CC (a tradition of interdisciplinary work in the liberal arts) could create a special learning experience for students at both institutions."

Now at Grinnell College, Stiles is also a visiting faculty member in the Physics Department at Colorado College. His plans at Grinnell include investigating an independent study regarding the physics of flight that potentially could link to the USAFA in a new collaboration. Following completion of the CC-USAFA physics course, the Mellon Foundation has granted another three years of funding for collaborative work between Colorado College and the USAFA, which might replicate this successful project or support new initiatives between these two institutions.

The following items come from Bryn Mawr’s findings on the use of blended learning in the liberal arts:

- When faculty decided not to continue [to use blended learning], it was through cost-benefit analysis:

- I won’t be teaching course again/frequently.

- Available materials don’t work, and developing my own would be an inefficient use of my time.

- In other words: LAC faculty are rational actors when rejecting as well as adopting technology.

These findings highlight the challenges for faculty in all academic disciplines of either developing or finding high-quality online resources. Others should review and use the evidence provided in that report regarding the potential positive impacts of blended learning in STEM courses to motivate additional collaborative work.

© 2013 Neal D. Barlow, Steven Brandt, and Randall J. Stiles. The text of this EDUCAUSE Review Online article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 license.