Key Takeaways

- This case study examines how one multi-campus, multi-state higher education institution used technology to support a transformative reaffirmation self-study process involving almost a hundred individuals.

- Although highly integrated, Antioch University places a premium on the distinctiveness of its five regional campuses, with integration and uniqueness both playing out through IT's transformative role in the reaccreditation process.

- One of the most important lessons is that vision should always take the lead and the tools should follow, not the other way around.

Accreditation is the currency of legitimacy in higher education. One of the high-stakes rituals is the 10-year reaffirmation of accreditation. Many colleges and universities understandably frame the process almost entirely in terms of complying with accreditors' expectations and getting the job done, rather than as an opportunity for organizational learning and renewal. Trying to make the reaffirmation truly meaningful in the face of many other pressing demands is often just too much to tackle.

At the same time, accreditors themselves are making extensive changes in requirements and processes in order to comply with federal expectations and a rapidly changing education landscape. One aspect of that change is moving away from paper-heavy processes to entirely digital processes for document collection, curation, storage, and distribution.

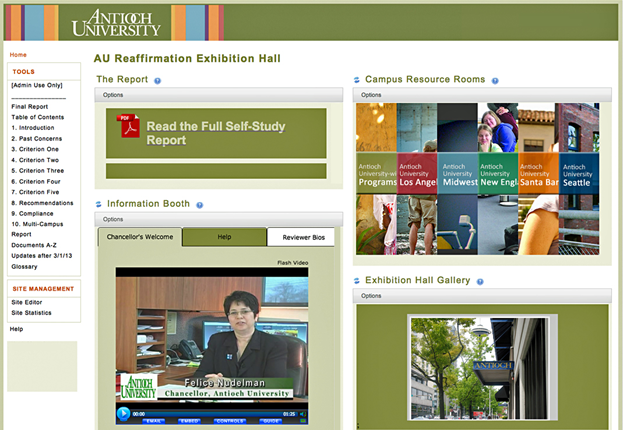

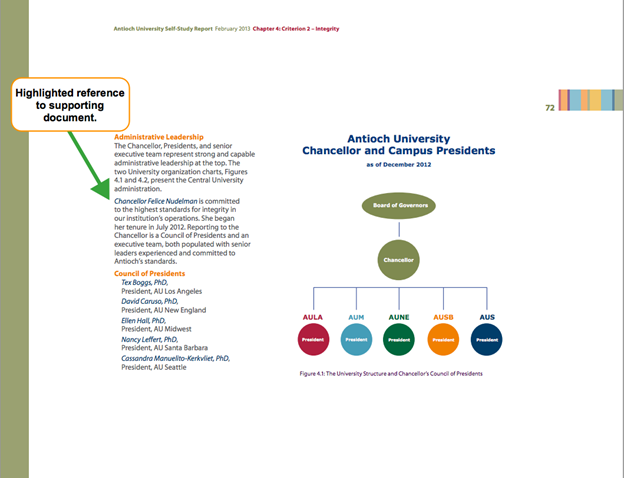

This case study examines how one multi-campus, multi-state institution, Antioch University, used technology to support a transformative reaffirmation self-study process involving almost a hundred individuals. We also examine its culminating product, a digital Self-Study Report and companion comprehensive electronic resource room, known as the Virtual Exhibition Hall (figure 1). In the course of that journey, Antioch confronted limitations — its own and those imposed by the tools — and made IT choices based on both vision and capacity.

Figure 1. Home page of the Antioch University Virtual Exhibition Hall

The Context

Antioch University is composed of five campuses in four states, with a history dating back to the founding of Antioch College in 1852. Over the past decade, prompted by both internal and external pressures to create a more effective and sustainable system, Antioch has shifted from a loosely federated model to a highly integrated institution that places a premium on the distinctiveness of its five regional campuses. Both issues — integration and uniqueness — played out in the transformative role of IT in the reaccreditation process.

Beginning in summer 2010, Antioch University began organizing its multi-tiered self-study process in preparation for its 10-year reaffirmation of accreditation. From the outset, there were a number of challenges related to IT's role in this process:

- First were the communication and collaboration needs of multi-state and cross-campus constituencies.

- Second were the self-study's evidentiary needs for securing, storing, and accessing digital documentation from hundreds of sources using disparate IT tools in order to adapt to processes that were in constant flux.

- Finally, representational needs also challenged IT capacities, as we had to imagine the virtual means of presenting Antioch University as a singularly accredited institution in fulfilling the accrediting body's five criteria while also presenting the distinctive campuses. Our tools needed to both consolidate and differentiate with ease.

We also had to keep pace with the evolving requirements and expectations of the Higher Learning Commission (HLC). Starting in fall 2011, the HLC began requiring that the more than 1,000 institutions under its 19-state umbrella electronically submit reports and other filings, substantive change requests, and all materials related to the reaffirmation of accreditation. This seemingly straightforward change has many repercussions for the accreditors and for higher education institutions, as Antioch soon discovered.

Accreditation Goes Digital

Accreditation agencies are moving toward entirely digital processes for all institutional submissions of substantive change, annual reports, and, yes, self-studies. Eliminating the proverbial onsite resource room with its stacks of papers awaiting visiting accreditation review teams has been prompted by several issues:

- Accrediting agencies must preserve these records for a minimum of 20 years, which has meant that the accreditors have had to microfiche decades of hard-copy documents, a time-consuming process that makes retrieval laborious.

- Review teams regularly did not receive accreditation materials in advance unless hundreds of pages were printed and mailed to reviewers to read prior to site visits, a system which was burdensome, environmentally wasteful, and unlikely to produce the desired results of pre-visit preparedness anyway.

- Review teams had little time to read materials when onsite, despite the labor-intensive preparation of these resource rooms by the institution, because visit days are packed with tightly scheduled meetings.

Going digital has eliminated these problems for accreditors but has created others. As one HLC vice president of accreditation recently noted, "Now that there are no file cabinets, we find some institutions doing a digital document dump," meaning indiscriminately posting everything into an electronic environment with little discernment and even less organization. While in some cases such document dumping might obfuscate particularly unpleasant information that institutions prefer reviewers not find, for the most part, it means reviewers have an incredibly difficult time making sense of the digital stacks and trying to find the materials they need in order to do a thorough review.

The investment of staff time and resources coupled with sufficient IT sophistication and bandwidth required to do this well presents a challenge for many schools, large and small. In addition to the intense multi-year self-study process of convening groups and developing, collecting, and analyzing evidence that demonstrates fulfillment of criteria, institutions now have to think about platforms, e-formats, aesthetic functionality, accessibility, searchability, security, and much more.

A "Sustaining" Innovation: Make It Meaningful and High Quality

Although we didn't know all our IT needs when we began the self-study process, the vision of an inclusive organizational process and of a high-quality product that presented an integrated university with distinct campus cultures was imperative.

Convening across Distances

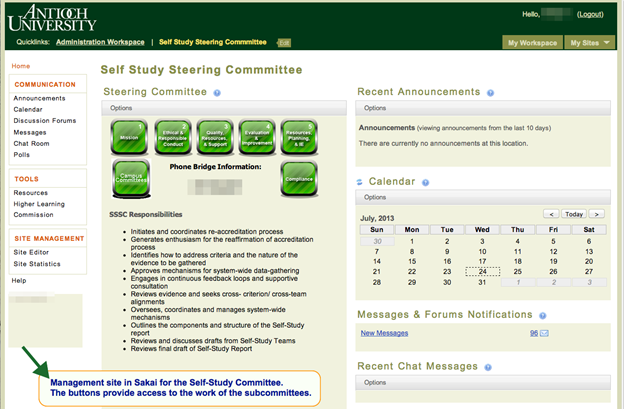

The easiest part was making choices about how IT would support the self-study's deliberative and consultative process. To ensure engagement of more than 80 individuals in four time zones over 2.5 years required establishing a stable baseline means of communication. High-end video conferencing tools were too costly and too demanding in terms of infrastructure; rather, we relied on basic systems already in place including phone, e-mail, Google Hangouts, and a joint Sakai site for posting agendas, documents, and sharable information (figure 2). These tools proved effective, and Sakai, our simple LMS, worked just fine as the baseline location for communication and collaboration across time and distance.

Figure 2. Self-Study Steering Committee Sakai site for posting and sharing materials

IT Choices: Trying to Make the Complex Simple

It soon became clear that whatever IT tools we employed, they needed to:

- Be fully integrated with our existing identity management infrastructure to provision user login and assign a variety of roles for both materials collection (back-end) and materials presentation (front-end)

- Have sufficient granularity to allow multi-tiered role-based permissions on the back-end

- Provide web-based publishing options for the front-end that allowed public, organizational, and role-restricted views for some materials

- Allow a fairly large number of individuals with various technology skills to easily upload files

- Store metadata for each file to facilitate identification, tracking, and use

- Be easily searchable both by title and metadata

- Provide an organizational view of documents that could be sorted easily by document type and campus location

- Handle document versioning with a clear and accessible history

- Manage the separation of "the wheat from the chaff"

- Make it possible to flexibly reorganize collected content to accommodate shifting choices regarding how to publish, to meet both changing HLC requirements and evolving thinking regarding the report's organization

- Provide easy-to-use web-based publishing options that readily accommodated the incorporation of design elements into a site that had aesthetic appeal and that aided in content location and site navigation

- Allow existing human resources to manage the above within existing administrative and design skill sets

The Self-Study Steering Committee, a 12-person university-wide body composed primarily of the chairs of criterion teams and headed by the university's vice chancellor of academic affairs, oversaw the development and collection of evidence over an 18-month period. At this stage, the IT challenges became a bit more complicated.

As we contemplated our collection and storage requirements, we recognized that we needed one unified solution back to front, collection to presentation. Antioch University is small: The institution didn't have the resources or infrastructure to support a wide range of applications for each separate part of the process. We needed to figure out a seamless pass from the collection process to the storage and access period to the ultimate presentation and publication stage.

Hundreds of documents came in various iterative stages of completion from varied sources for multiple purposes at different times. We needed to ensure that the evidence gathered was easily accessible for a changing set of parties. We rejected automated approaches during this early phase because there were simply too many unknowns for sufficient precision about a singular location or particular use or universal format. Each piece of evidence therefore required manual handling, from initial collection to reposting for other uses by other teams, to converting into different formats from Word to PDFs, and so on. Obviously, this was labor-intensive, but we felt it was necessary.

After a few starts and stops, an organizational topology for the back-end storage folders was identified. We tested naming protocols hoping to find the best approach for "at a glance" searchability down the line. Should the primary naming index be by campus, type of document, or relevance to one or more criteria? Here, too, we changed approach because our accrediting agency revamped criteria halfway through our process, which required us to rename documents, reconstruct teams, and rearrange storage folders.

Figuring out a seamless process from collection to storage to presentation was at the core of the IT conundrum. Our available options came close, but no single application ultimately met all these needs. Antioch University's digital Repository and Archive (AURA) seemed a viable choice, and conceptually it made sense to house critical material such as a reaccreditation report in our repository. The product was designed to handle the submission of article drafts, editor review, resubmission, and eventual web publishing. Though a bit cumbersome to manage, it had all of the essential back-end functionality and offered a means of releasing the material to a web front-end, so we proceeded to train all Steering Committee and Criterion Team members on the repository product.

However, document management proved too complex to manage, given our resources and staffing. And although it was technically possible to manipulate some elements of the front-end web design in AURA, options were limited and did not provide the flexibility we needed. The deal-breaker, however, was in access management: The system was not integrated with our identity management system. Without major effort on the back-end through work with the vendor, content could only be released as fully public, and our primary audience was our internal constituents and the HLC peer reviewers. Given our fast-moving timeline, we used this repository for some of the early stages of document collection, but without the ability to easily restrict some published content to the university population and others to the reviewers, we ultimately rejected it.

The IT department offered a newly installed SharePoint server as an alternative. However, this massive, high-stakes self-study process would have been the institution's first initiative to use SharePoint, and the IT department was just beginning to develop expertise in its use. We also did not have web designers who could have made full use of SharePoint's front-end.

The remaining possibility was our LMS. Initially, Sakai had looked unappealing. It was a largely out-of-the-box installation with skin elements that would govern the look of our final web product. The tools were sound in structure, but basic and separate, complicating their use in high-quality web presentation. Sakai offered a pre-structured home page with a single content block that could be manipulated with a web editor (figure 3), but all other pages were a click down to a tool. We were extremely familiar with the use of Sakai's simple design for courses and project sites, but not for something like what we were contemplating. In the end, our familiarity with the tool and its simplicity were compelling.

Figure 3. Off-the-shelf Sakai home page template

The easy-to-use folder structure, in combination with experienced Sakai users, made this a less stressful and more manageable operation for campus administrators. It also facilitated speedy project team document handling and tracking. The role-based user component of the LMS made it easy to add individuals to a site and control access to materials. And, although we had originally assumed a need for automated versioning, reaccreditation documents require repeated human review and handling. A human version-manager proved a better option than a digital approach. Thus, although we were many months into the self-study process, we manually shifted our collection process and all stored materials from the university repository to Sakai.

Putting It All Together: The Self-Study Report and Virtual Exhibition Hall

Antioch University's Self-Study Report followed a simple organizational structure given the already inherent complexity of the university as well as HLC's changing criteria. While not particularly unique or creative, we chose to organize the Self-Study Report and its chapters by the five HLC criteria, 21 core components, and 68 subcomponents. University-wide Criterion Teams developed substantial outlines through an iterative consultative process, and eventually the Self-Study Committee Steering Chair wrote the final report to ensure consistency of voice and style throughout the narrative.

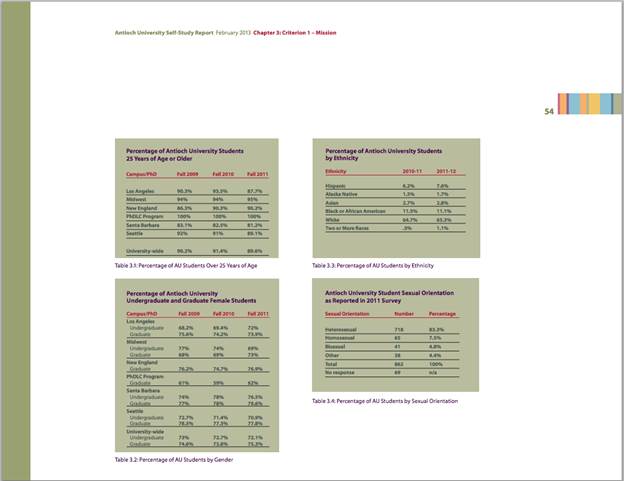

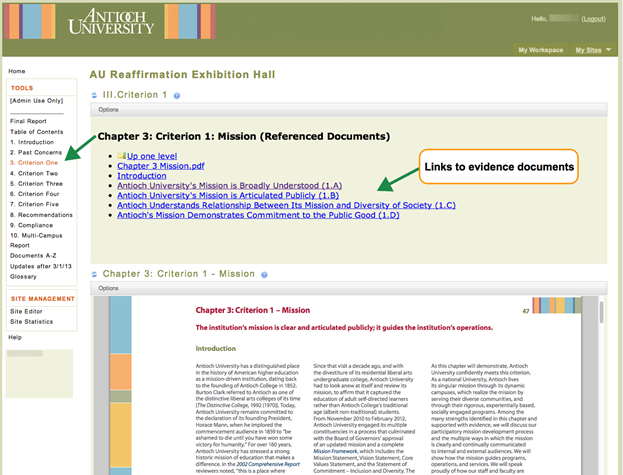

The IT-related challenges in writing the 250-page report mostly had to do with aesthetic functionality: to use design in ways that enriched the electronic document by taking advantage of the format without being seduced by too many bells and whistles. A guiding principle for presentation was that aesthetics should enhance readability and not get in its way. Tables and charts used color sparingly to assist the reader in marking location or theme (figure 4). Initially we thought the report would include direct hyperlinks to hundreds of supporting materials, but we changed our minds because of the enormity of the task, limited staff time, submission deadlines, and the fact that we would need to create two entirely different reports — one for the internal public and one for the review team members linked to confidential information. Instead, the final report indicates supporting documents in a bold/italicized typeface in the narrative (figure 5); all are available in the electronic resource room.

Figure 4. Minimal and consistent use of color in charts and tables

Figure 5. Hyperlinks to supporting documents

The biggest IT-related "sustaining innovation" in the self-study process involved the transformation of the electronic resource room into a site useful for reviewers, aesthetically appealing for visitors, and institutionally meaningful to our internal constituencies. In the end, the robust, interactive site has easy-to-download chapters, supporting documents accessed by chapter subsection or indexed title, rotating galleries of photographs of people and locations, engaging videos, and more.

Six months prior to submitting the final report and going live with Antioch University's Virtual Exhibition Hall, a small five-person production team began weekly meetings. Team members included the Self-Study Steering Committee Chair, another key committee member, a part-time graphics designer, an instructional strategist/designer who acted as liaison with the IT department, and a staff member responsible for archiving and posting to the site. Team members lived in three states, so all production meetings were conducted virtually.

As the official document resource room, we knew the Antioch University's Virtual Exhibition Hall needed to provide reviewers with easy access and logical navigation to hundreds of documents. We also wanted to present Antioch University and its five campuses as an integrated, mission-rich institution that honors its regional distinctiveness. Of course, we needed to assemble and curate evidence to demonstrate criteria fulfillment. But, we also needed to bring to life the people, programs, and passion of Antioch University.

Animated walkthrough of the Virtual Exhibition Hall (1:29 minutes)

As with other stages in the self-study process, we had to be flexible as we tried IT tools and approaches only to reconsider and change course when they didn't meet our needs.

Having decided on Sakai on the front-end, we now needed to consider its capacities on the publishing side. Although Sakai's web content tools are extremely easy to use, we definitely had concerns about the way Sakai segregated presentation of content. This led to a "what if" exploration of the Sakai structure that resulted in a "eureka!" moment. It proved possible to manually build pages on the back-end of Sakai and bundle the output of various tools on single Sakai pages — resulting in simple, clear, contextualized materials and navigation. In other words, we used our Sakai site not as a means to access tools, but as a framework within which to build a highly utilitarian, coherent web presentation.

Our deep dive into how Sakai pages could be used in a more integrated way became particularly important once we decided that each campus would have its own Campus Electronic Resource Room (CERR) within the larger university Exhibition Hall. We heavily restructured Sakai pages to function as mini-sites within the whole. Manually constructing pages allowed us to create a very easy way to navigate CERRs and establish a presence for each campus as if it were its own mini site within a single larger site, keeping organization, navigation, permission, and role management extremely simple (figure 6). It also created opportunities for aesthetic approaches to facilitate the user experience, a "discovery" that has led to a much more powerful use of Sakai for our courses and other project design efforts.

Figure 6. Resource rooms for each campus

To address the aesthetic issues, we designed a simple skin that used a banner drawing from the graphic design of the final Self-Study Report and a color-coding scheme for each campus to make them readily identifiable. In addition, the university IT department provided a web developer to write basic code for special design elements such as a graphic slider to navigate to the companion site for campus materials and a tabbed inset for the creation of an information booth for the reviewers.

Demo of the graphic slider (20 seconds)

Explanation of the Information Booth's tabbed structure (24 seconds)

This information booth housed video welcomes from Chancellor Felice Nudelman and campus presidents, video support for navigating the sites, and reviewer bios.

Welcome to team members from Chancellor Felice Nudelman (1:26 minutes)

Author Laurien Alexandre, chair of the Self-Study Steering Committee, explains and shows how to navigate the resource rooms (2:43 minutes).

The Hall Goes Live!

In setting up the Virtual Exhibition Hall, we created a site for reviewers and a separate version for internal constituencies — not our original plan. The reviewer-accessed, password-accessible Main Exhibition Hall and CERRs include confidential materials; the mirrored version, with confidential material removed, is open to all Antioch students, faculty, and staff. Our original intention of one site quickly reversed on the day we went live, only to discover within 15 minutes that the Sakai architecture nullified our approach to managing role-based access to secure materials. Thus, the only way to quickly and reliably ensure security was to create separate sites.

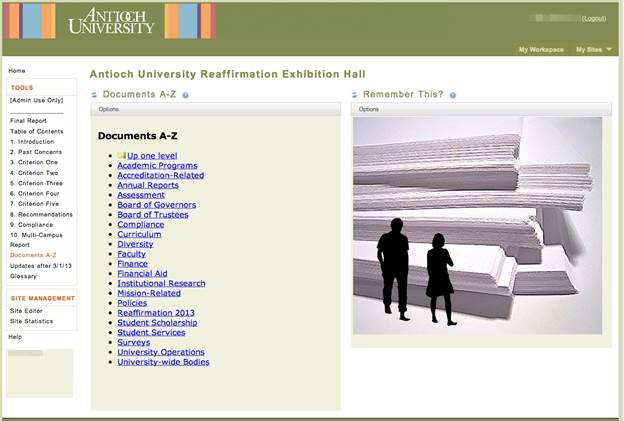

The final weeks of loading the Exhibition Hall were incredibly labor intensive. Hundreds of documents mentioned in the Self-Study Report were reviewed and renamed for a final time to match references in the text. The evidence was structured as an A to Z list (figure 7), and then from that list, evidence was linked to the report in chapter folders (figure 8).

Figure 7. One way to access: evidence documents listed from A to Z

Figure 8. Another way to access: evidence linked to report chapters

So, the Verdict Is…

The Self-Study Report was submitted to the HLC Review Team in January 2013. The Exhibition Hall went live soon thereafter. Each team member received a password and log-in instructions to the secure site. Antioch faculty and staff simply enter the open version of the Exhibition Hall once they log into the university's Sakai site.

Over the course of the five-month process of sequential site visits to all of our five campuses as well as to central offices (with the first in April and the last in August), reviewers have visited the Exhibition Hall over 50 times. Additionally, we have loaded over a dozen new documents since the initial site visit.

One essential perspective in answering the question whether we created an Exhibition Hall that met and exceeded the requirements of our review team and met our vision is found in the comments from one review team member, who noted:

"Unlike some online resource rooms that I have experienced, the Antioch Exhibition Hall was well-organized and very easy to use. Instead of what some teams have referred to as 'data/document dumps,' this one was intuitive and easy to go back to when we wanted to check on items. The site was colorful and alive, conveying the dynamism of the campuses. Uniquely, there were videos, color, and movement as different sections were accessed. Before we arrived at each physical site, we had been on tours of facilities and met the resident leader in a warm, welcoming message. Overall the site was not only functional but it was also informative and promotional. It conveyed a highly professional image of the university."

Another review team member commented:

"The Antioch Exhibition Hall provided a well-organized and intuitive way to follow the documents, which were organized by self-study chapter as well as a complete A to Z list of documents referenced in the self-study. In addition, I could search for documents by topic, e.g. academics, support services, governance, etc. A 'one step up' feature allowed me to start on a topic at the program level and go up to the institutional level by area. There was careful delineation of the individual five campuses that was very helpful in visiting the campuses as part of the overall team visit. It was very easy to find a distinct view of the campuses with a video introduction from the campus President as well as documents specific to the campus. The set-up allowed an easy back and forth from the campus section to the overall institution documents.

"A particularly attractive part of the Exhibition Hall was the use of videos within the structure. I found the videos to be very helpful in getting a feel for the primary administrators before the visit. For instance, there was an introduction from the Chancellor as well as the self-study coordinator. Both focused on how to use the Exhibit Hall presentation as well as an introduction to the institution and self-study process.

"Overall the Antioch Exhibition Hall was well-designed, intuitive, graphically pleasing and was a critical and helpful tool for my work as a team member."

Welcome from David Caruso, campus president at Antioch University New England (2:12 minutes)

Dale Johnston talks about the Self-Study Report and process.

Comments from the Antioch community have also been positive. Those who participated in the multi-year Self-Study Steering Committee efforts praised IT support for our process. Self-Study Steering Committee faculty member Dale Johnston noted, "Although there were some bumps along the way, the system worked extremely well. … The Exhibition Hall proved to be particularly effective for demonstrating the integration of the university and at the same time highlighting the distinctive character of each campus."

Steve Chase explains the value of continued access to the site.

For members of the wider Antioch community who have visited the site, the reaction has been equally positive. It provides a robust representation of the entire university, and users can go into campus rooms to learn about other campuses. As noted by Steve Chase, an Antioch University New England faculty member, "As a rank and file environmental studies professor on the New England campus, I learned new things about my university and developed a much stronger appreciation and identification with Antioch University as a whole. I continue to drop in in my spare time and learn more. It would have been completely impractical to make all these documents available to faculty as paper documents, but now I have access to all the supporting material for our self-study report for years into the future."

Another university faculty member, Elizabeth Holloway, commented, "Across the university, teams of faculty and staff came together to consider the kinds of criteria that were needed for the accreditation report. In each case, not only was there a production of information but there was a sense of unity. This was a report that just didn't stay on a shelf...this was a report that talked about future vision."

Elizabeth Holloway talks about future vision in the self-affirmation report (2:10 minutes).

Laura Andrews shares her reactions to the Exhibition Hall.

Staff member Laura Andrews added that "walking through the Exhibition Hall was a delight" and made her "proud to be a member of the institution." She was reminded of "our history in a way that was inspiring."

While the outcome of the entire reaffirmation process is still in the hands of the accrediting agency, it is our assessment that IT enriched our self-study process and product immeasurably.

Lessons Learned

CIO Bob DeWitt talks about IT support and lessons learned.

The IT innovation in Antioch University's self-study effort rests with the creative uses of technology that were available to us but were not set up or designed for our needs. How we used the technology — stretching, coddling, enhancing, and adapting — resulted in a high-quality, user-friendly, and reliable presentation using simple technology. The bottom-line lesson for us and for other institutions embarking on their self-study process is that simple and inexpensive tools can produce high-quality products. In terms of lessons learned, Antioch University CIO Bob DeWitt noted, "The most important lesson we learned was about the importance of understanding the information collection and presentation needs of the study from the beginning." He reflected on how the assignment of a dedicated, high-level technical expert to the Reaccreditation Production Team enabled the group to brainstorm and prototype possible presentation approaches in real-time. He commented, "We came to appreciate that the technical requirements of the Production Team were constantly evolving as the requirements set by the accrediting body on the university also evolved, and so it was important to break down barriers in order to facilitate rapid development."

IT capacities unquestionably enriched relational efforts across the university's five campuses, building university-wide cohesion and collaboration. At a time of institutional disruption and major change, IT tools facilitated our ability to sustain an integrative self-study process of engagement and a distinctive self-study product that makes us all proud. The lesson for us and others is to let technology do what it can do best — bring virtual teams together to collaborate, enable effective document collecting and sharing, and provide platforms for publishing in creative ways.

One of the most important lessons learned is that vision should always take the lead and the tools should follow, not the other way around. Too often institutions get enamored with the latest and greatest IT platform, but it really doesn't serve their needs. Perhaps because Antioch simply does not have the infrastructure or resources to go for the bells and whistles, we not only made do with what we had, we made it work for us. We knew what we wanted in the process and in the product, and that led every one of our decisions.

© 2013 Laurien Alexandre and Wendy McGrath. The text of this EDUCAUSE Review Online article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 license.