![Viewpoints [Today's Hot Topics] Viewpoints [Today's Hot Topics]](http://www.educause.edu/apps/er/images/viewpoints2010.jpg)

Higher education technology leadership is rewarding, dynamic, and challenging. During my twenty-five-year career, I have witnessed significant change. I cannot imagine a better period of time to have led technology transformation on a campus.

One critical challenge I have addressed throughout my career is supporting my staff to embrace this change and to connect with campus colleagues. In my experience, this is best achieved through storytelling. In that spirit, I share some of my stories here.

Leveraging the Water Cooler

When I was hired for my first IT management job (in 1987), I was thrilled. However, the situation was a bit complicated because one of my new subordinates had also been in line for the job and was upset that I had been hired.

My new job came with the usual three-month probationary period, which I was not concerned about. But I clearly remember the day my boss called me in to his office and explained that my probationary period had been extended. The staff member who had been considered for my job was dissatisfied with my work and had expressed concerns to my boss. As a result, my boss extended the probationary period, primarily to show my staff member that her concerns were being taken seriously. I was shocked. I had relocated to a new city for this job and was working 8 a.m. to 8 p.m., five days a week and sometimes on the weekend. I was completely focused on doing the work, and I was loving the challenge.

I was angry that my hard work was not enough. In reaction, and partially to get back at my boss, I decided to slow down my efforts. Instead of intensely focusing on the work, I spent time chatting, getting to know people, making personal connections. Instead of jumping right into the work at hand, I would start by asking people how they were, spending good time listening, and sharing more about myself.

At the close of the extended probation, my boss told me that the extension had been pro forma; he hadn't thought there was a problem. Yet he added that whatever change I had made was a significant improvement. The feedback he had received from my staff, peers, and colleagues spoke of much stronger relationships across the board. I was told to keep doing what I was doing. This was my first formal on-the-job lesson in leadership. Getting results is important, but building relationships is critical.

Hiring Right

A friend of mine managed a nonprofit organization's warehouse where clothing donations were collected for distribution. She loved her job, except when she had to help fold the incoming clothing. She could not imagine how anyone could spend the day doing the dull, repetitive work of folding clothes.

I remember speaking with her when she was in the middle of hiring a new team member, whose primary job would be to fold clothes. She was sure there was no way anyone would want the job, so she crafted a description that played up other, more interesting aspects of the job and downplayed the folding. The job description worked: she received great candidates and was able to hire a wonderful person.

A while later I checked in with her, and she was distraught. In six months she had hired three excellent people for this job, but they did not stay. She wondered what she was doing wrong. As we talked, it became obvious: her hiring process was less than honest. She needed someone to fold clothes. I suggested she change her approach and emphasize that the job was all about folding clothes. I implored her to put aside her own bias and find a clothes folder. She took my advice, changed the approach, and found a fantastic clothes folder who stayed with her for years.

This lesson taught me the importance of honesty in hiring and the power of a diverse team. A team leader must be realistic about what someone will have to do to be successful in a job and must value those qualities. We are strengthened by our differences. To this day, I continue to be pleasantly surprised that there are people for all kinds of jobs.

Orienting for Success

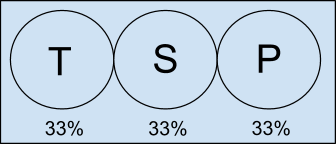

Over time I have developed a vision for success that I call "the three circles." I use this model in staff meetings and when hiring new staff in order to create a common outlook for my team. It's a "recipe" for success, hence the abbreviation for teaspoon.

"T" stands for "technical skills," which is how staff are hired—for their technical skills. We also train people to help them develop their technical skills and to keep those skills current. We look for people who not only have the skills of today but also are willing to grow and change to acquire the skills of tomorrow. This thirst for remaining relevant and a love of learning make our technical staff truly outstanding. But that's not enough to ensure success.

"S" is for "social organization," or the culture of the organization. For technical staff to be truly valuable, they need to understand the way the IT organization works and also the way the college/university works. Having deep technical skills without social understanding is analogous to writing a great software application that can't run on any operating system. Social understanding connects the campus wants and needs to the power of digital technology, which enables the mission. Having both technical skills and an understanding of the social organization gets staff 66 percent of the way to success.

"P" stands for "political skills." Many mistakenly believe that these skills are reserved for managers and directors, yet everyone within the IT organization needs to be able to handle political issues. Although the CIO and directors need to work with the president, deans, and administrative leaders to articulate and shape IT priorities, this shaping can be successful only when the rest of the organization supports the IT story and language via relationships that forge strong bridges across the campus. Obtaining supportive budgets and developing implementation timelines are other ways political skills encourage both individual and group successes.

TSP in Action

I once had a talented staff member who, during his yearly evaluation meeting, described the specialized computer programs he had developed the previous year. I was surprised and pleased. His contributions were substantial and could have contributed much to increasing the productivity of the organization.

I asked him: Who used his programs? Where was the documentation? Who was trained? How was the information being shared? He looked at me strangely and said that he didn't think any of that was his responsibility. Like factory products that are moved into the warehouse and never distributed any further, one's work has value only if it is applied and functional.

We had a long conversation, and I explained TSP to him. We spent most of our time talking about "S" and "P." We explored the need to engage with team members and campus customers. We discussed why being able to build things with strong technical skills does not necessarily create value. We talked about why being connected with people was critical. As this became clear to him, he noted: "Of course, IT services are valuable only if they are able to be adopted." Understanding how things work in the larger organization makes all the difference.

Funding the Common Good

Many years ago, when I first assumed budget responsibility, I worked in an organization where our campus customers paid for their desktops out of their own budget. The IT department did the procurement and charged back the cost of the machine. As a new manager, I defended and stretched my budget, treating it like the scarce resource I knew it to be. Through my cautious management and vigilant chargebacks, I was able to accomplish much.

My financial management worked well until the late 1990s, when we realized that everyone had to use anti-virus software. The IT service desk couldn't keep up with the infected computers, and our networks were propagating the problem across the campus. We negotiated for a site license and told all departments to buy the software for their desktop computers. The fee was about $5 per desktop, a great price. The only problem was that the departments would not pay and therefore would not use the software.

Frustrated, I went to my CFO for support. I made my argument about the importance of the software and the great price we had negotiated. I requested that he support this effort and issue a directive for departments to pay for and use the software. As I finished my argument, he smiled and handed me a book on environmental law. He had opened the book to one particular case: "The Tragedy of the Commons." The case explained that no one wanted to pay for public lands and that left unmanaged, public lands would always degrade. My CFO noted that the network was a public land and that if I cared about it, the IT organization would need to pay for the software.

As a result of "The Tragedy of the Commons," the IT organization paid for the software, installing it in all departments at no charge. Required participation was (and is still) not a model easily adopted in higher education. Success in this case was based on working for the good of the campus community. In the end, the IT organization recovered staff time and effort while significantly decreasing the number and breadth of infections.

+++++

My team and I use these stories as a framework from which to develop a common vision and to establish norms. I encourage the addition of new stories, to teach us about who we are as an organization and how we want to operate. I encourage leaders to consider the narratives in their lives and to share those stories that help us shift our understanding and improve our leadership skills. Together, these stories become the team's stories, forming a common narrative and ensuring our shared success.

© 2012 Carol Katzman

EDUCAUSE Review, vol. 47, no. 5 (September/October 2012)