Key Takeaways

- The Oregon DATA Project aims to improve student achievement through training teachers about strategies for accessing, analyzing, and using data to target instruction to the needs of individual students.

- Although the main participants are K–12 districts, valuable feedback comes from university representatives who meet with the project director quarterly to receive updates on project activities, and then identify issues and concerns related to teacher and administrator training.

- The project's professional development model consists of five phases: field input, in-service training, job-embedded professional development, pre-service training, and evaluation.

- After just two years, results indicated that teachers have made tremendous progress in adopting classroom-level data-driven decision making, connecting data to their teaching approaches.

There is an increasing expectation that school improvement efforts and initiatives aimed at closing the achievement gap will be driven by solid, reliable data. This requires well-designed data systems, but it also requires that teachers use this data effectively and then adapt their instruction to improve student learning. "Data systems are a vital ingredient of a statewide reform system," said Secretary of Education Arne Duncan. "But having the data isn't enough. It's essential to use the data to drive student achievement."

There is an increasing expectation that school improvement efforts and initiatives aimed at closing the achievement gap will be driven by solid, reliable data. This requires well-designed data systems, but it also requires that teachers use this data effectively and then adapt their instruction to improve student learning. "Data systems are a vital ingredient of a statewide reform system," said Secretary of Education Arne Duncan. "But having the data isn't enough. It's essential to use the data to drive student achievement."

In Oregon, the problem is not that teachers lack data — in fact, they have access to a dizzying amount of information from more than 125 different assessments used throughout the state. But having access to data is not the same as using it effectively to inform instruction — that is an undertaking requiring knowledge, practice, and skill.

Having significantly invested in its data systems for the past 15 years, the Oregon Department of Education (ODE) sought to bridge this gap with an initiative that would provide stakeholders with comprehensive training in effective use of data.

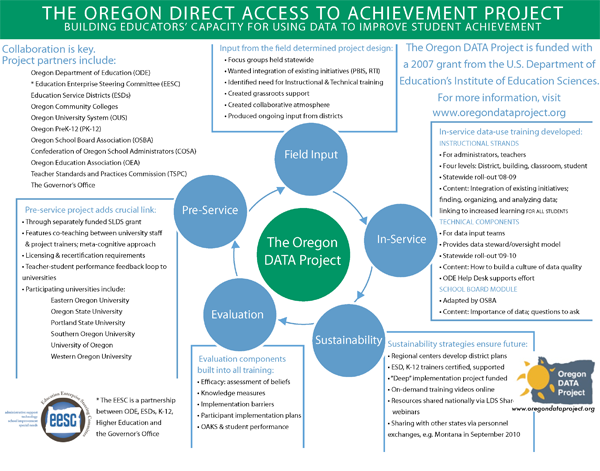

In June of 2007, the Institute of Education Sciences awarded Oregon a four-year, $4.7 million grant to implement the Oregon Direct Access to Achievement (DATA) Project (see figure 1). The Oregon DATA Project's goal is to improve student achievement through professional development that helps educators access, analyze, and use data to target instruction to the needs of individual students.

Figure 1. The Oregon DATA Project at a glance

DATA Project Overview

The ODE organized its Oregon DATA Project initiative in collaboration with several organizations, including the Education Enterprise Steering Committee [http://www.oregoneesc.org], the Oregon Association of Education Service Districts, the Oregon School Board Association, the Confederation of Oregon School Administrators, and the Oregon University System [http://www.ous.edu]. The Data Quality Work Group, a multi-agency steering committee that meets twice a year, provides guidance for the project's direction. Although the DQWG was initially formed to help chart the DATA Project's direction, it now provides guidance on a number of ODE's data initiatives.

The state's 19 education service districts (ESDs), which offer support and services to the districts in their areas, provided the framework on which the project was built. Through the Oregon DATA Project, the ESDs were grouped into six geographical regions. Representatives from the group, as well as experts from K–12 and ODE, worked with the project director to develop five strands of instructional training [http://www.oregondataproject.org/content/instructional-training] based on the needs of the field. Each region then helped roll the training out to the field and supported school districts as they worked to embed a culture of data literacy in their schools. Currently, about 140 of the state's 200 school districts are participating in the initiative. Training for school boards is also offered through the project through certified trainers from the Oregon School Board Association.

Author Mickey Garrison, Director of the Oregon DATA Project, explains the project's training strands (2:26 minutes):

Although K–12 districts are the main participants, an important higher-education element has been incorporated: Oregon university representatives serve as a valuable feedback loop. The DATA Project director meets with universities quarterly; higher-education reps receive updates on the project's activities and, in return, identify issues and concerns related to teacher and administrator training, both undergraduate pre-service and graduate certification. The project's certified project trainers co-teach several assessment courses with university faculty, several of whom have also been through the certification process. The project also serves as a valuable field resource for higher education, with trainers being asked to present on current assessment topics from the school and teacher perspectives.

Professor Heitho Reuter of Western Oregon University shares her experience with the Oregon DATA Project (0:33 minute):

Denny Bain, a Western Oregon University student and Corvallis teacher, shares his experience (0:20 minute):

The Five Project Phases

The model of professional development created by the Oregon DATA Project consists of five phases: field input, in-service training, job-embedded professional development, pre-service training, and evaluation.

The field research phase consisted of 15 focus group meetings in eight locations across the state. More than 180 people, including superintendents, principals, teachers, technology staff, classified staff, and parents, were asked how best to use data to improve student achievement in Oregon, and what kind of challenges they currently faced.

Input from the field was used to develop two main tracks of training for the project's in-service training phase: instructional, for teachers and administrators; and technical, for data-entry personnel.

The technical track provided districts with a model they can use to build a "culture of data quality." Within the instructional track, five strands of training were developed that addressed data use at the district, school, classroom, and student levels. The general focus of the sessions is on accessing, organizing, and analyzing data to inform instruction. The training also includes a focus on Essential Skills (reading and writing), and implementation of the Common Core State Standards. Topics under development include authentic classroom assessments and expansion of the Essential Skills modules to include math and science.

In the project's third phase, sustainability became the focus, as it supported the work of seven regional centers. These centers, made up of clusters of Education Service Districts, supported participating districts in job-embedded professional development that built strong data teams and professional learning communities. More than 300 educators from ESDs and K–12 districts were certified in facilitating the project's team process of using data to inform instruction and improve student achievement. Curriculum resources are also available on demand through the initiative's website and through instructional DVDs, about 1,000 of which have been distributed to date.

The DATA Project also supports pre-service training for undergraduates in university programs, as well as education professionals in graduate programs. In addition, evaluation is a strong component of the DATA Project, as we describe later in the "Evaluating the Work" section.

Challenges and Lessons Learned

One of the project's major challenges — getting buy-in — was apparent from the outset when focus groups were held around the state. Teachers were understandably concerned that the project would give them one more system to deal with.

The project was therefore designed to integrate existing systems used in the field: Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports, Effective Behavioral and Instructional Support Systems [http://www.ode.state.or.us/search/page/?id=1389], Response to Intervention, and Literacy Framework [http://www.ode.state.or.us/search/page/?id=2568]. As the project rolled out, participants appreciated that their concern had been addressed. In addition, the project's emphasis on seeking out stakeholders' opinions contributed to an unprecedented atmosphere of collaboration and grassroots support.

Teacher leader Becky Stoughton of the Redmond School District talks about her participation (0:39 minute):

Trainer Daymond Montieth, Curriculum and Assessments Director, Klamath Falls City, stresses the benefits of having multiple trainers (0:42 minute):

Although the project did a good job of reaching teachers with this approach, as the project moved into sustainability mode — where support for data teams increasingly rested with the districts — it became apparent that more time should have been invested upfront in training administrators on how to analyze data and support teams.

The project also included many other lessons learned:

- Provide more training on soft meeting skills (how to conduct productive meetings) in conjunction with data analysis.

- Invest more time in training teachers to use analyzed data to improve instruction.

- Create a few initial "lab" sites that can be used to demonstrate what the process — and effective teams — look like.

- Build capacity and sustainability by training certified staff to be trainers in the certification process.

- More closely monitor deliverables for the project library to ensure needs are met and gaps are filled.

- Organize session videos by unit theme instead of replicating the training agenda.

- Use memorandums of understanding with districts to clearly outline their commitment to the project's work.

- Establish criteria for the number of certified trainers for each region to ensure adequate support.

Evaluating the Work

An independent evaluation [http://oregondataproject.org/content/evaluation-report] of the Oregon DATA Project concluded that the initiative has had a positive impact on student achievement. It also found that participating districts are meeting Adequate Yearly Progress (AYP) at a higher rate than non-participating districts.

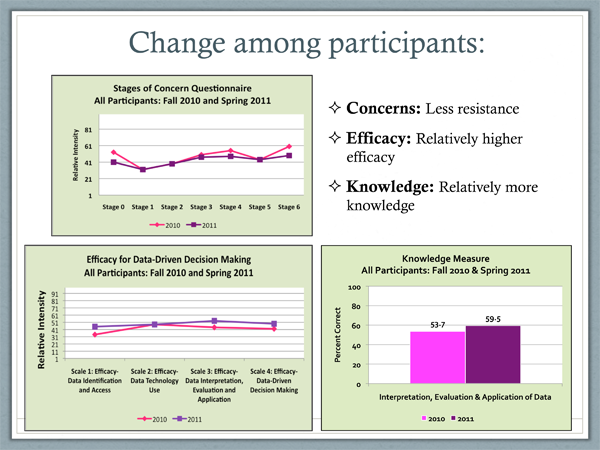

Connecting data to instructional action results in a differentiated learning environment as well as increased student performance. In our case, third-party evaluators from the University of Arkansas monitored the impact of the project's job-embedded training and traditional seminar training. (See the spring 2011 evaluation report [http://oregondataproject.org/content/evaluation-report].) After only two years of work at the teacher level, the results of assessment and qualitative analysis of activity logs indicated that teachers have made tremendous and swift progress toward adopting classroom-level data-driven decision making (DDDM), connecting data to teaching (figure 2). Experts in organizational change note that large-scale change of this type typically takes a minimum of three to five years.

Figure 2. Rate of teacher adoption of classroom-level DDDM

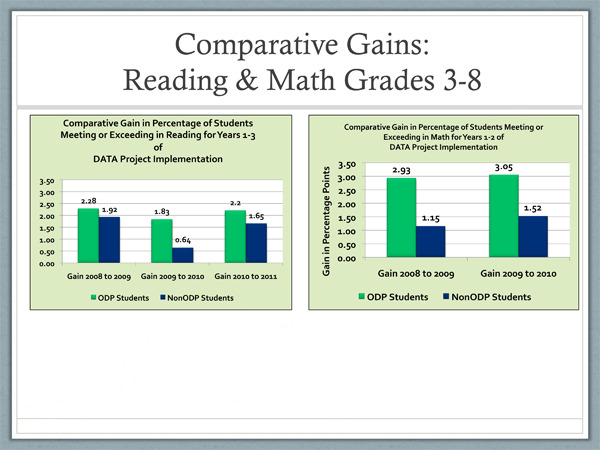

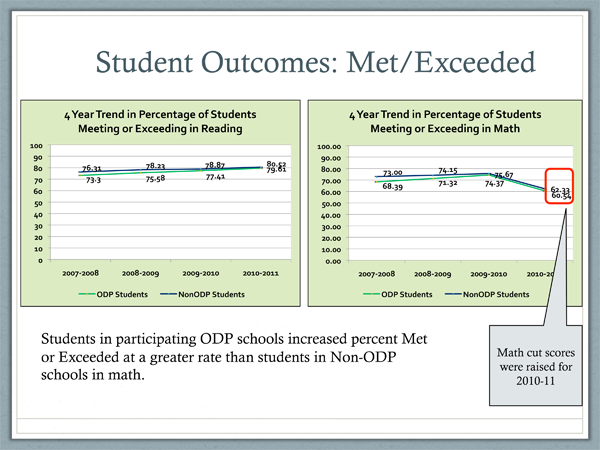

Student-level data analysis indicated that students likely benefited from these increases in teachers' DDDM. At the onset of the Oregon DATA Project initiative, non-participating schools performed at higher levels in both reading and mathematics. Over the course of the project, participating students experienced greater gains in the percentage of those who met or exceeded standards in both reading and mathematics than students in non-participating schools (figure 3).

Figure 3. Percentage gains by students in participating vs. nonparticipating schools

Overall, reading is not an area of weakness in Oregon, but the gap between student reading performance in non-project schools and Oregon DATA Project schools decreased. Participating schools also experienced significant gains in the percentage of students who met or exceeded standards in reading each year of this initiative (figure 4).

Figure 4. Trend in student achievement in participating vs. nonparticipating schools

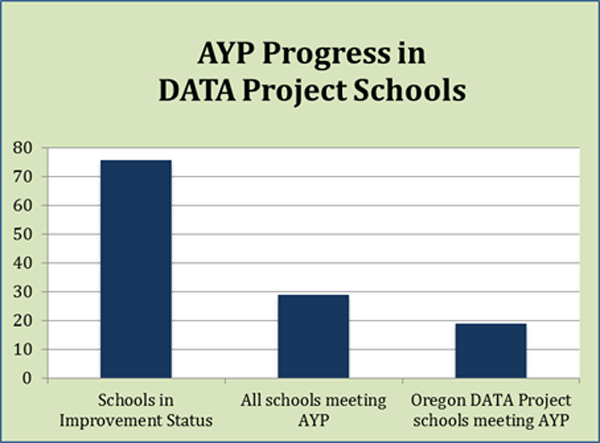

The effect of improved student achievement on accountability is illustrated by the recently released preliminary ratings [http://www.ode.state.or.us/opportunities/grants/nclb/titleistatus2010-11sy.pdf] for Oregon public schools meeting federal AYP. In 2010, 29 of the 76 Oregon schools listed as Schools in Improvement met AYP in the subject that placed them in that category. Of those schools, 65 percent (19 schools) are participating in the Oregon DATA Project (figure 5).

Figure 5. Of schools meeting AYP, 19 participate in the Oregon DATA Project

Collaboration Yields Results

One of the most important features of the learning model developed by the Oregon DATA Project is its focus on needs in the field. Before the project's direction was set or any strands of learning developed, extensive communication was undertaken with stakeholders in the field through focus groups, personal visits, and presentations from the project director, as well as many, many phone conferences with district and ESD personnel.

In addition, the project's training was nimble, and trainers frequently adjusted content in response to participants' needs and a changing assessment landscape.

Participants responded positively to the project model, which called for regional rollouts of training strands, followed by job-embedded professional development.

Jesse Pershin, Principal of Rogue River High School, talks about his experience with the Oregon DATA Project (0:22 minute):

The model's collaborative nature — where K–12 and ESD trainers do the bulk of the training — is also helping build a statewide network that breaks down the barriers of geographic isolation. Teachers across the state are contacting each other to share ideas and resources, transforming the state of Oregon into one large professional learning community.

We think this model, with its responsiveness to the needs of participants, is applicable to any educational setting.

For More Information

See the "Oregon DATA Project: Year 5" [http://oregondataproject.org/content/year-5-report] report for a historical view of the entire project.

© 2012 Mickey Garrison and Megan Monson. The text of this EDUCAUSE Review Online article (July 2012) is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No derivative works 3.0 license.