Key Takeaways

-

Students often attempt to navigate the Internet without being given the space to intentionally think about and understand how the digital world works, how it influences their lives, and how they in turn can influence its direction.

-

Liberal arts colleges emphasize preparing students to be lifelong learners, creative and critical thinkers, and engaged members of whatever communities they enter after college, but how do they prepare their students for the digital world?

-

Following a workshop on liberal arts colleges and digital citizenship, representatives from four higher education institutions share their varied experiences in cultivating digital citizenship awareness and capabilities among their students.

Why are people sharing news stories about things that didn't really happen?

What are these ads that keep popping up on my Facebook page?

Will new net neutrality rules really affect me?

These are the kinds of questions our students face every day. Often, they have no clear answers as they attempt to navigate the Internet with little to no education about how the digital world works. Sure, as avid social media users they often teach us how to use a new app or gadget, but do they understand the repercussions of living a life online and the rights and responsibilities that come with that digital presence? We are working to find a way to ensure these kinds of discussions and lessons find their way into our classrooms and into students' preparation for life beyond college.

In addition to information literacy, we struggle to educate students about their privacy and the massive amount of personal data they unknowingly and sometimes unwillingly shared in the digital realm. For example, Facebook was accused recently of collecting data about young people who show signs of insecurity and using that data to enable targeted marketing that exploited those insecurities. Some argue that this is no different from traditional advertising in any medium, but the questions of privacy, ethical uses of big data, and balance of benefits and risks in using a "free" social networking service are all in play. Meanwhile, many of our students remain unaware of these tactics or consider them business as usual. So how do students begin to think about curation of their digital identities within particular environments, and how might they individually and collectively influence the policies and practices of those who design those environments?

Fake News: Two professors at the University of Washington, Carl Bergstrom and Jevin West, have created a website meant to accompany a potential college seminar entitled 'Calling Bullshit.'

Today's postsecondary education must focus on critical thinking, security, and empowerment as we move collectively into an uncertain digital future and seek to influence its shape and affordances. Liberal arts colleges emphasize preparing students to be lifelong learners, creative and critical thinkers, and engaged members of whatever communities they enter after college. In the 21st century, our graduates enter a world in which the landscape of economic, civic, social, and intellectual discourse and activity are profoundly shaped by digital tools and platforms. How do institutions who value these characteristics prepare students for this digital world?

We had been grappling with this question at our own institutions — St. Norbert College, Keuka College, Capital University, and Bryn Mawr College — for a few years before we met one another. We found the process of comparing the courses, projects, and programs we were developing as potential solutions to be extremely helpful for refining our objectives and strategies. In January 2017 we brought this conversation to the wider higher education community in the form of a workshop, "Digital Citizenship in the Liberal Arts Community," at the ELI Annual Meeting. This article summarizes some of the challenges and conclusions each of us experienced on our own campuses.

What Do We Mean by Digital Citizenship?

What digital citizenship means at any given institution is influenced by institutional context. What happens when you get 50 people from different but similar contexts in a room trying to agree on a definition of a complex term like digital citizenship? At the EDUCAUSE Learning Initiative 2017 Liberal Arts Workshop, we found some agreement across our institutional contexts that engagement, empowerment, critical thinking, and moral or ethical responsibility are the descriptors that we see as core to "citizenship," including its digital forms.

Citizenship could imply good citizenship. However, who decides what is "good"? To address this complexity, we as authors agreed that "citizen" in this context is a placeholder for "people within a community," community being the contexts where we live, learn, and work.

We also debated the value of calling out the digital facets of citizenship and determined that there are indeed unique questions to ask about digital environments and interactions within them. They often have unique legal or pragmatic elements due to the ways digital systems work and the ways we operate within them. Focusing on the digital also allows us to ask explicitly how and when particular digital technologies enable us to do something in a way that we could not in the analog world or with traditional methods.

Why Digital Citizenship?

Currently the Internet of Things, complex social media networks, and virtual and augmented reality are emerging technologies. We want our graduates to develop an awareness of their digital practices and help them determine how those technologies are designed, built, and distributed in their fields and their communities. When students matriculate, we place them in a more formal, localized layer of digital tools with our administrative and learning systems. Using Dave White's visitor/resident mapping exercise with different groups of students across our four institutions, one of the commonalities we found was a distinct separation between tools used for school and tools used personally. Students often do not see or understand how systems that live solely in the institutional realm work, but rather use them as isolated tools having little to do with their identity building. If students had a better understanding of how our institutional systems defined them, could this allow students to have a better understanding of themselves?

Being able to grapple with the complexity of our rights and responsibilities with the implications of our decisions, as individuals within diverse communities, has always been key to whole-person learning and to preparation for life beyond our institutions. When unpacking digital citizenship, we must ask not only about rights and responsibilities when online, but also about how our everyday lives are affected by the integral role digital systems and networks play in our communications, interactions, policies, and practices. Giving students the opportunity to define and answer these questions easily aligns with the tenets of a liberal arts education but also with the wider landscape of higher education. Because these questions are addressed with a focus on critical thinking, navigating complexity, and multidisciplinary perspectives, which are important to higher education as a whole, they address gnarly challenges and frame critical digital inquiry for continuous learning.

We also want to acknowledge the body of work that has been developed on digital citizenship for K–12 audiences. This work is essential and focuses mostly on safety and appropriate behavior that go along with moving in and out of supervised environments. We can build from this work as we look more deeply into engagement, empowerment, critical thinking, and moral or ethical responsibility.

Table 1. Digital citizenship: a tale of four initiatives

|

|

Carnegie Classification |

Enrollment Description |

Programs Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Capital University, Columbus OH |

Comprehensive,mid-sized, private |

Approximately 2,700 undergraduate and approximately 700 graduate students |

Approximately 60 undergraduate liberal arts and professional majors with graduate programs in law, business, music, education, and nursing |

|

St. Norbert College, De Pere, WI |

Baccalaureate college, arts and sciences focus, community engagement |

Approximately 2,100 undergraduate and approximately 100 graduate students |

More than 40 majors, minors, and pre-professional programs |

|

Keuka College, Keuka Park, NY |

Masters, small private college |

A 125-year-old liberal arts-based, residential institution serving approximately 1,100 FT students at its home campus, plus another 900 adult students at two branch campuses and several extension sites |

13 professional undergraduate majors, 20 liberal arts undergraduate majors, and 8 graduate programs |

|

Bryn Mawr College, Bryn Mawr, PA |

Baccalaureate college, arts and sciences focus |

Approximately 1,350 undergraduate and approximately 350 graduate students |

Liberal arts college for women with co-ed doctoral programs in six Arts & Sciences fields, a Graduate School of Social Work & Social Research that has just celebrated its 100th anniversary, and a Postbaccalaureate Premed program |

Capital University

Autumm Caines, Associate Director Academic Technology and Adjunct Instructor

During our recent half-day workshop at the 2017 ELI conference in Houston, Texas, four universities led a discussion about various approaches to digital citizenship. We explored the fact that digital citizenship is not a nicely packaged and clean deliverable for universities to implement. Universities cannot foster digital citizenship through a single turnkey solution. As the associate director of Academic Technology at Capital University, I am just beginning to explore how digital citizenship might be implemented at the university, starting with the classroom. Here, I focus on digital citizenship at the course level by reflecting on a first-year seminar course about digital citizenship that I developed.

Digital citizenship as a theme for a first-year seminar course lays a foundation for students about the nature of the Internet and the various roles that they can play online. The class challenges students to see past the idea that the Internet is just a place for advertising or socializing by looking at the web as a place to build an identity for the purpose of networked learning. The larger conversation around critical thinking and the transition to university life intersects and overlaps with conversations about digital identity, the changing nature of digital environments, and our rights and responsibilities when we are online.

Several years ago, Capital embraced the idea of an interdisciplinary first year seminar offering with guiding work of the John Gardner Foundations of Excellence program. First year students choose from a variety of first year seminars courses that have been developed around diverse themes. All of the courses have foundational discussions about transitioning to university from high school and what it means to be a first year student. However, each class is also unique in that faculty design and personalize their course around themes. A theme of digital citizenship at the course level with first year students allows us to think about the web as a place for learning at a critical time in students' development.

Objectives for all of the first-year seminar sections at Capital University include critical thinking and reading, visual and information literacy, communication skills, interdisciplinary perspectives, and reflection on adjusting to life in a higher education community. The connection between these objectives and digital citizenship are clear; for example, reflective and engaged digital citizenship requires critical thinking, visual and information literacy, and communication skills.

I highlight two practical aspects of the digital citizenship theme that enable the course objectives: Domain of One's Own and Networked Learning.

Domain of One's Own

In the class, students take an active role in evaluating their online practices and considering online identities that they hold as well as those that they would like to develop. Through a Domain of One's Own project students craft a public identity for the course as an undergraduate scholar and have the option to craft additional identities through the use of subdomains or subdirectories, which allows for building of technical literacies and competencies. From a developmental perspective, the ability of students to design multiple identities and receive feedback from others helps them better understand who they are becoming as they move from late adolescence into adulthood. I have only had the opportunity to deliver the course once, but interestingly, after a discussion about the different ways to parse naming conventions, all of the students chose to claim a root domain for a personal identity and to set up the class blog on a subdomain, showing a more nuanced understanding of the different ways to present themselves online and a desire to own a piece of the web. This is important because the identity work takes place in the context of conversations about ownership. Ownership as a concept is a troubled one, especially on the web, so foundational discussions around crafting domain names and claiming space are essential. Most importantly, we explore this concept specifically in terms of students owning their learning.

Networked Learning

Digital literacies and competencies give us the ability to use digital tools; however, connecting ideas and contexts requires a higher level of cognition. The seminar provides opportunities to use the internet as a place to network with people in other cultural contexts who also want to use the web as a place for scholarly reflection. I accomplish this by scheduling video conversations, shared projects, and twitter chats with educators, scholars, and students in similar classes from around the world. Students need to understand that on the web their audience may exceed their intended audience — anyone with a connection might come across their posts. Meeting with educators like Maha Bali, a proficient blogger and an associate professor of Practice at the American University in Cairo, via a video call (figure 1) allows my students to not just think about public discourse in a variety of cultural contexts but also to converse with someone from a different cultural context about these matters. Another example of networked learning would be when we connected with other first-year courses taught by Robin DeRosa at Plymouth State University and George Station at California State University, Monterey, to share text annotation and a twitter chat. In this way, the class networks with others having similar conversations, thus broadening students' academic sphere of influence and peer groups beyond institutional borders.

Figure 1. Digital Citizenship students speaking with Maha Bali

The seminar also focuses on other aspects of the internet. We read terms of service, consider the ways that our identities are tracked to maximize goals that might not be in our best interests, and imagine ways that our digital identities could be exploited. Students leave the course with a critical eye toward digital environments and those who own those environments, but begin to think of the web as a space where the possibility of self-expression exists.

As a technologist and administrator I have found that teaching this course adds value to my own professional development. Being able to try out the technologies I want to explore in my own classroom enables me to better advise faculty I serve in my full-time role. The course will be available for registration again this fall, and I'm excited to again engage with students around these important questions.

St. Norbert College

Krissy Lukens, Director of Academic Technology

Sundi Richard, Instructional Designer

Hillary, a first-year student, sits in in a room with her advisor for the first time. When and how will she be introduced to the concept of digital citizenship? What opportunities will she have to make sense of what it means to her and how it relates to other things she does during her time at a four-year residential liberal arts college? When she graduates, what will she take with her as a digital citizen?

At St. Norbert College, our approach has been to identify initiatives already in place on our campus that cultivate and explore digital literacies and digital citizenship. We then make connections with these initiatives in an attempt to foster and grow these areas along with student, staff, and faculty awareness of the importance and presence of digital citizenship. A large part of this is connecting to our liberal arts tradition, which calls us to dialogue with diverse cultures, perspectives, and beliefs; cultivate a love of lifelong learning inspired by excellent teaching; and think critically as responsible members of society. We also draw from our Norbertine mission of "Whole Person Development": fostering intellectual, spiritual, and personal development both inside and outside the classroom and promoting the development of whole persons by cultivating practices of study, reflection, prayer, wellness, play, and action. These include digital spaces, which are often not considered. We need to draw attention to these spaces by using (at least for now) the quantifier "digital." These two parts of our mission guide and inform what digital citizenship might look like for our institution. Although the following by no means describes all the pieces, it tells part of the story.

The Course Level

Neal is about to graduate as an English major. His program has included a range of learning experiences: He has been in lectures that have sparked his motivation to explore Frida Kahlo's life and work and has been in a writing workshop where he learned to collaboratively give feedback and take notes online as a way to create community and trust within a small group.

A Full Spectrum Pedagogy model, developed by Reid Riggle, director of the Digital Learning Initiative (DLI), was adopted into the 2016–2020 Strategic Plan, to expose students to the full spectrum of pedagogical techniques by encouraging and enabling faculty to use the pedagogy best suited to their subject matter and incorporate contemporary teaching practices. This model was developed to both recognize the value and presence of traditional styles/techniques and to encourage a range of impactful instructional methods, including those that use technology to elevate learning.

We affirm both the validity of "tried and true" methods of instruction that have a long history and enduring presence in higher education and the large potential for instructional enhancement offered by the new learning technologies. Ideally, students would be exposed to a rich diversity of pedagogical styles across the four years of their experience at SNC, integrating the old with the new, in consonance with the Norbertine dictum, "Ever ancient, ever new."

—Reid Riggle

The model is meant to encourage using pedagogies that open classes and expose students to experiences outside of the school's walls, an important aspect of developing a more diverse self.

Faculty Development

As a second semester visiting professor, Elena had a fairly full schedule, but wished to continue to explore her own pedagogy. She sought out faculty development that she could flexibly work into her schedule and in which she felt supported by the institution.

The question that follows the Full Spectrum Pedagogy model is, "How do we help and equip faculty to experiment with a diversity of pedagogical styles that include exposing students to work within open digital environments?" #DigPINS (Digital Pedagogy Identity Networks and Scholarship) is one faculty development course created to address this need. It is based on the idea that it is important to give faculty opportunities to develop their digital identity, which then influences their pedagogy. A fully online, four-week course, the content fosters the development of digital identity, developing online networks, exploring critical digital pedagogy, and thinking about what this means for faculty members' scholarship. While participants read about and discuss these topics, they do so immersed in both closed and open online spaces. The course is small and growing slowly. During 2016–2017 it ran three times with 22 participants. Faculty buy-in is key to growth, as faculty who took the course spread the word and got their colleagues involved.

Faculty-Driven Initiatives. As a direct result of the #DigPINS course and the discussion of developing one's identity in open spaces, three art faculty members jointly applied for a Digital Learning Initiative mini-grant to run a one-semester pilot of Domain of One's Own with three art courses. Their goal was to work on the reflection and portfolio pieces already happening in those courses, but also to give students a chance to do this in a space that would enable them to:

- Think about their digital identity

- Develop web literacy and skills during assignments/projects

- Give them control of what they create and the choice of whether to continue building after the end of the course(s)

All of these are key areas of what we see as digital citizenship.

Reaching Students Directly (LeaderShop and #Digciz Workshops). As a group that works mainly with faculty, the Academic Technology team also wanted to reach out to work directly with students. One way was to offer a one-hour workshop that faculty could request if it related directly to course content. Another was to offer a student development workshop if a faculty member planned to be traveling. These one-class sessions were meant both to find out more about how students approach their digital identities and to start a conversation about how and why they might want to think about the ways they were developing in online spaces.

Student Affairs approached us to help with a Digital Leadership Workshop that was part of their LeaderShop series and one of many student leadership workshops that they put on throughout the year focused on students who were part of different organizations on campus, but open to all. Being able to bridge some of the silos and find out what others on campus are doing is a continued part of our efforts.

In both types of workshops, we used the Visitor and Resident Mapping exercise to start a conversation about digital identity, which helped us understand both the spectrum of students' digital lives and how for many (most) of them, those digital lives had little to do with their conception of their self-development as college students.

Is the Institution on Board? (St. Norbert MOOC, #SNCMOOC). When Hillary was choosing where to go to college and was looking at small liberal arts colleges, taking an online course was not part of her plan. In fact, she had never taken one and was a little hesitant because she really enjoys being in a class with other students. However, the semester before she started her degree she was invited by the school to participate in a Massive Open Online Course, run by the college president, about the college's namesake. She was a busy high school senior, but through the flexibility of the free course, which allowed participants to decide how much they participated, she was able to get a sense of the atmosphere, values, and mission of the school in a way that she had not experienced before.

Fully online courses sit at the far right of the full spectrum pedagogy model. While the college has offered online courses before — primarily during winter and summer terms — this past spring the president of the college and a Norbertine priest offered the college's first MOOC or cMOOC, titled "St. Norbert: The Man, the Movement, the MOOC." While reaching a diverse audience (parents, alumni, Norbertine communities, the wider public) to share knowledge about a lesser known saint, participants gained opportunities to develop digital literacies involved with learning online. Many of those who became involved at the institution and many of those who participated did not have much familiarity with MOOCs or open courses before starting #SNCMOOC.

Although offering the course had several key goals, one of them was demonstrating the college's commitment to trying new modes of engagement and instruction. Often, at the institution level digital identity is tied to recruitment, marketing, and broadcasting campus news. This was a chance to connect the institution's digital engagement with its mission.

Future

Neal experienced a range of courses that prepared him to approach problems and situations in a variety of ways. These courses appear on his transcript, but, now graduating, he does not have the opportunity to fully articulate all that he has done.

Two initiatives to build on student digital citizenship include digital badging and our Gateway Seminar. The digital badging initiative [http://badges.snc.edu/] is meant to serve as both a guide and recognition for students exploring co-curricular activities. After fully participating and demonstrating competence in a co-curricular experience, students earn a digital badge, creating a record of meaningful experiences during their career at St. Norbert College. Additional digital badges are being considered for Teacher Education Dispositions, Career Readiness, and Digital Literacies.

The Gateway Seminar, a 2016–2020 Strategic Plan Activity, will provide a First-year Experience. Among other things, it will prepare students to successfully complete the transition to college and the first semester of college. The seminar focuses on academic practices and integrity; college-level writing proficiency; digital citizenship; and personal, intellectual, and spiritual growth and development. The first Gateway Seminar is set to begin fall 2017.

It has become evident to us that more efforts could be made in the digital realm of engaging in dialogue with diverse cultures, perspectives, and beliefs. This is one area where we will seek to partner with campus colleagues for continued growth and practice.

Keuka College

Annie Almekinder, Director of Digital Instruction< /p>

Enid Arbelo Bryant, Assistant Professor of Communication Studies

Nancy Marksbury, Assistant Professor, Digital Learning & Services Librarian

Angela Narasimhan, Assistant Professor of Political Science

Keuka College was founded in 1890 by a Baptist minister with a vision. After 125 years that mission might look quite different, but the emphasis has not changed. Keuka College remains committed to comprehensively integrating liberal arts, experiential learning, and professional practice. Today, though, the role of digital technologies is ever present and must be incorporated to ensure we are creating thoughtful graduates who will play a crucial role in society. Our case study defines a recent instructional project and an ongoing, college-wide initiative that reinforces aspects of digital citizenship and the possibilities and limitations of digital technologies.

Our students learn the skills necessary to reflect on their own conduct and behavior by applying social responsibility and ethical purposes in a complex and now digital world. Keuka College's institutional vision to become a leader in higher education by integrating digital learning into and across the liberal arts curriculum was established in 2013; today it includes a Digital Studies minor focusing on communication, creation, and analysis. DL@KC has benefitted from the support of both administration and our trustees, and by dedicated faculty who continue to drive its development. The term "digital citizenship" entered our vernacular when a group of Keuka College faculty approved a set of student learning outcomes. It was then that digital citizenship for Keuka College was operationalized as: "Students understand human cultural and societal issues related to technology and consider the moral, ethical, and legal implications of their digital behaviors."

Taking inspiration from Karen Harpp from Colgate University, who developed a semi-private online course, The Advent of the Atomic Bomb, a team of Keuka College faculty built a selective, private online course (SPOC) to examine the presidential campaigns and election of 2016. We were prompted by reports of increasing voter apathy and declining civic engagement of people in the 18-to-29-year-old age group. As educators and parents, we asked, "What can we do to influence students' political participation and civic engagement in their broader communities?" Although this generation has ample opportunity to engage with causes and issues through their easy and frequent access to information online and social networking sites, we wanted to create a digital platform that could guide and develop their use of such tools toward that end goal of greater direct political participation in this particular election cycle. We invited students, community members, alumni, and faculty to join conversations that investigated our democratic process and the influence of media on the campaign, and to discover how we align with people in our community, state, and nation. By embedding a political community inside our online platform, we were able to expose participants to different generational perspectives, personal viewpoints, and disciplinary approaches through an experiential learning model that connected the election and current events with digital skills such as data mining, creating infographics and video broadcasts, blogging, and other forms of virtual collaboration.

Our SPOC was offered during the fall 2016 semester, and we paired the experience with distinct units from several traditionally offered courses that helped students and other participants engage with particular aspects of the election (see table 2).

Table 2. SPOC timetable

|

|

|

|---|---|

|

Week 1 |

Digital Timeline identifying when this election began for you |

|

Week 2 |

The American Political Culture |

|

Week 3 |

Campaign Issues: Where do you stand? |

|

Week 4 |

Debate and Election coverage |

|

Week 5 |

Education, Immigration, and Globalization |

|

Week 6 |

Media Coverage of Politics: The Role of Bias |

|

Week 7 |

Political Science Faculty Panel; Meet & Greet of local judicial candidates |

|

Week 8 |

The Supreme Court: History, Politics, and Implications for the Future |

|

Week 9 |

The Influence of Money on Politics |

|

Week 10 |

Media Analysis: Bias and Perspective on News Coverage |

Alumni and members of the community greeted this opportunity enthusiastically: 105 people from this category signed up, and 53 of them ended up participating significantly. In addition, 83 students were involved through class and project-related participation. An exit survey indicated that 40 percent of those students involved in the SPOC voted. Our closest measure of comparison is data from the National Study of Learning, Voting, and Engagement, which reported a 36 percent turnout for the 2012 presidential election among students at our institution. Although not a significant increase, our limited data suggests that this platform has the potential to improve voting turnout among students.

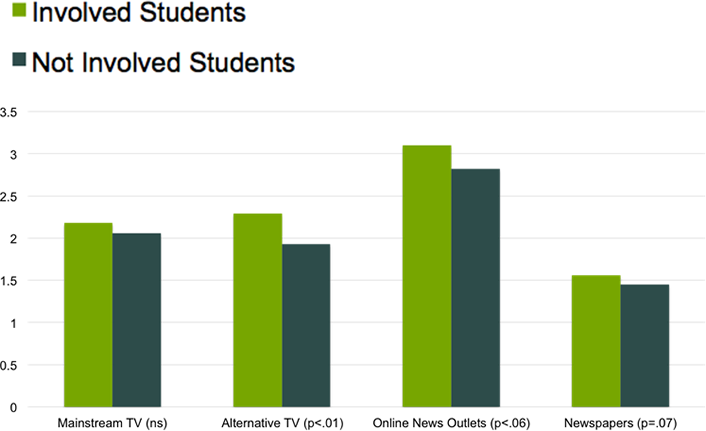

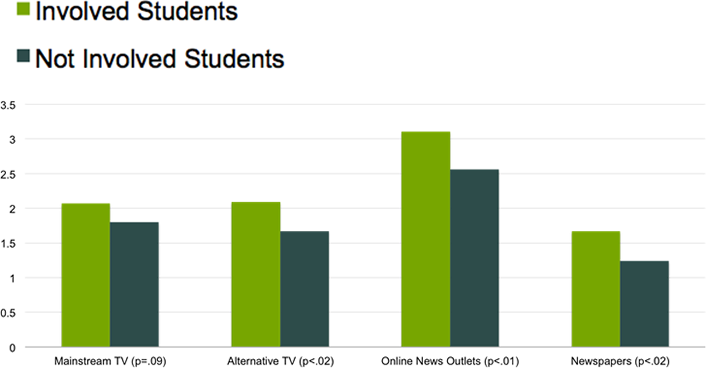

However, pre and post surveys of students involved in the SPOC and of those not directly involved suggest the SPOC may have influenced students' news consumption. Students were asked, "How often do you read/watch/listen to the following media channels to get information about events, public issues, and politics?" with answer choices of 1=occasionally, 2=once a week, 3=several times a week, 4=daily, 5=several times a day.Figures 2 and 3 show a comparison of mean student ratings of news outlet access before and after the 2016 presidential election. (Mainstream TV news channels were exemplified as ABC, CBS, NBC, CNN, Fox, etc.; alternative TV news channel examples were PBS, BBC, Al Jazeera, etc.)

Figure 2. Student ratings of news outlet access before the election (n = 198)

Figure 3. After the election (n = 127)

Differences between the groups were more notable after the election, suggesting that the course experience maintained student interest in news on events, public issues, and politics after the election. Online news outlets gained the highest frequency of student attention to news, which is predictable given its ease of access and currency, while TV as a news source dropped, but not significantly for both groups. Surprisingly, the mean frequency ratings for radio as an outlet were less than once a week and so were omitted from these graphs.

From our experience with the SPOC, we are buoyed by the small signs of longer-lasting impacts. Yet, for a small college, such an endeavor requires a significant amount of additional responsibilities without established resources. But asked if we would do it again? We answer Yes! quite emphatically.

Bryn Mawr College

Gina Siesing, Chief Information Officer & Constance A. Jones Director of Libraries

Jennifer Spohrer, Manager of Educational Technology Services

At Bryn Mawr College the "citizenship" element of digital citizenship is atmospheric rather than the explicit focus of our program. As a women's liberal arts college confronting a world in which women are underrepresented in the technical spheres, we have emphasized empowerment and agency over other aspects of digital citizenship. Our campus-wide Digital Competencies Program is designed not only to help undergraduates develop skills needed to communicate, engage, and work effectively with digital technologies, but also to recognize and celebrate that development.

While Bryn Mawr had committed to helping faculty, students, and staff develop digital fluencies and had had considerable success in increasing campus engagement in digital teaching, learning, and research, we were missing a holistic framework to help students knit their disparate experiences into a cohesive whole. For example, a typical student might be introduced to strategic and critical web searching and to metadata through a librarian's presentation in a first-year course; build data-management and analysis skills through a summer internship at a nonprofit arts organization; set up and manage a website for her rugby team; and take a course on Media in the City that uses critical theory to analyze media representations and communication in urban areas. The Digital Competencies Program provides a framework that helps students recognize that these moments contribute to their broader, ongoing growth in the realm of "digital competencies"; encourages them to own that growth; and gives them a platform, practice, and supportive feedback so that they can effectively describe their development, interests, and capabilities to potential employers or graduate application committees.

Bryn Mawr's mission is to develop our students' "critical, creative, and independent habits of thought and expression" and to encourage them to become "responsible citizens who provide service to and leadership for an increasingly interdependent world." We believe that in the 21st-century world, expression, leadership, and service are increasingly mediated by digital and networked technologies, which are themselves evolving at a rapid pace. Thus, in keeping with our mission, the goal of the Digital Competencies Program is to ensure graduates develop the habits of mind and practical skills needed to stay abreast of technological change and to make wise choices in the ever-evolving digital contexts in which they live, work, and play. Specifically, the framework was designed to help individual students:

- Identify the digital skills and critical perspectives they will need to be 21st-century leaders and contributors

- Seek curricular and co-curricular opportunities to hone these skills and perspectives while at Bryn Mawr College

- Learn how to articulate and demonstrate the competencies they develop for specific audiences

A Liberal Arts Curriculum for the Digital Age

Several recent college initiatives have helped increase the curricular and co-curricular opportunities for Bryn Mawr students to develop digital competencies.

Bryn Mawr is in its final year of a Mellon-funded grant project, Developing a Liberal Arts Curriculum for the Digital Age, which has focused on supporting technology-enhanced teaching practices within the liberal arts curricular model and on creating additional curricular and co-curricular opportunities for students to develop digital competencies. Faculty and staff can apply for funding and technical support to develop digital course materials, design a digital course assignment, and/or involve expert practitioners in courses. Educational Technology Services hires and trains Bryn Mawr undergraduates to support these curricular projects through two to six summer student internships and two full-time entry-level educational technology positions for recent graduates funded by the grant. These students and recent graduates work in small teams with professional staff and faculty; develop design thinking, project management, coding, and troubleshooting skills; experience working with clients; and learn various technologies as they help design assignments, resources, and tools that provide curricular opportunities for their peers to do the same.

Curricular projects supported through this grant include multimedia and web exhibition projects for courses in classics, history, sociology, anthropology, East Asian languages and cultures, education, and first-year interdisciplinary seminars; online tutorials and quizzes that enable faculty and staff to "flip" entire courses; library instruction; components of service learning; and study abroad advising, so students are better prepared for in-person class activities or consultations. Some of the most exciting innovations invite students to think critically about digital technology applications through hands-on experience. Students in "Critical Issues in Education" courses explore the impact digital technologies have on teaching, learning, and education by authoring and trying to publish Wikipedia articles, learning to play Minecraft from a teenage expert, or teaching elderly adults how to surf the web and communicate with relatives on a smartphone, for example. An assignment to build 3D models of ancient Roman buildings based on available historical and archaeological sources for a Growth and Structure of Cities course forced students to confront the question, "How do you represent 'maybe'?" (More information on projects is online.)

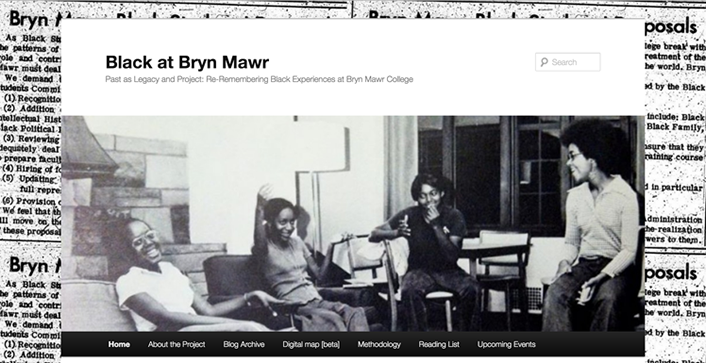

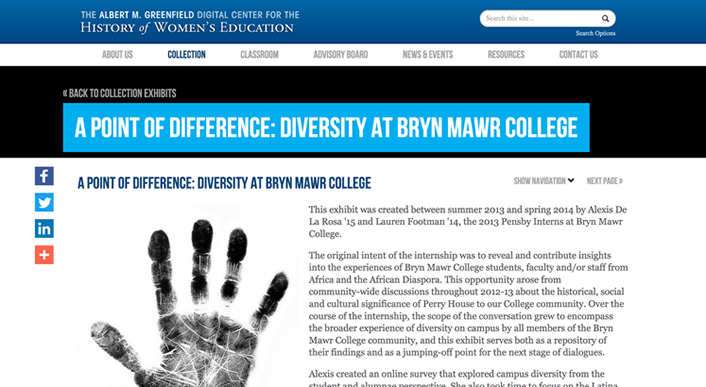

Bryn Mawr College's nascent Digital Scholarship Program is also enhancing support for faculty and student research, often drawing on Bryn Mawr's archives and primary source collections. Students have pursued independent research projects through internships in Special Collections, independent study, and Praxis Courses (Bryn Mawr's service-learning initiative), as for example, with the website "Black at Bryn Mawr" (figure 4) and associated walking tour researched and created by students and the website "A Point of Difference: Diversity at Bryn Mawr College" (figure 5) researched and created by students via Bryn Mawr's Greenfield Digital Center for the History of Women's Education.

Figure 4. "Black at Bryn Mawr" site

Figure 5. Digital exhibit "A Point of Difference: Diversity at Bryn Mawr College"

The Digital Scholarship Program has created fellowships, workshops, learning communities, and other opportunities that respond directly to undergraduate and graduate students' scholarly and professional development interests and faculty members' curricular and research project goals. A pilot of Reclaim Hosting's A Domain of One's Own will not only enable students to have a domain space in which they can develop digital projects and e-portfolios using the platforms of their choice (WordPress, Drupal, Omeka, Scalar, etc.), but also let them take these projects with them when they graduate. Student fellows and interns have also had opportunities to develop critical maker skills while developing 3D educational applications for Microsoft's HoloLens or wearables that visually represent class-year-related Twitter messaging during Bryn Mawr's May Day celebrations.

Putting it All Together

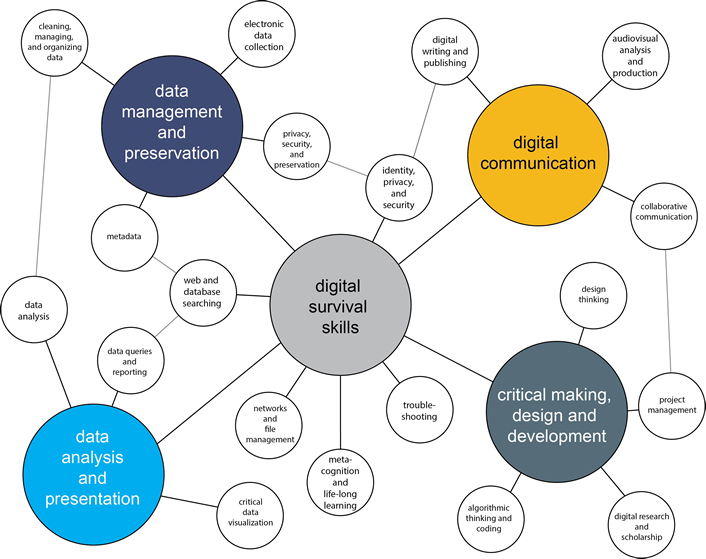

The Digital Competencies Program is designed to help students reflect on this broad array of curricular and co-curricular activities and articulate digital competencies they have developed in ways that are meaningful to them and to outside audiences. The program has been developed through input from faculty, students, staff, members of the Board of Trustees, and alumnae. It is a programmatic approach to fulfilling the guidelines issued in spring 2014 by a Digital Bryn Mawr Task Force convened by the Board of Trustees, namely: (1) foster digital fluency among students, faculty, and staff; (2) continue to develop uses of technology that are appropriate to the liberal arts college context; and (3) strive to be agile — that is, continually experiment, assess, learn, and iterate. The Digital Competency Framework, which groups competencies into five major, interconnected genres (digital "survival" skills; digital communication; data management and preservation; data analysis and presentation; and critical making, design and development), was developed by Library & Information Technology Services (LITS) staff working with faculty and students on curricular projects and honed based on feedback from from the key constituents, who provided perspective on their relevance to disciplinary study, scholarship, and work beyond college. The framework encourages students to view digital competencies as an interconnected web of experiences, critical perspectives, and skills (see figure 6).

Figure 6. Bryn Mawr's Digital Competency Framework (View larger image)

LITS is working closely with with LILAC, Bryn Mawr's Leadership, Innovation, and Liberal Arts Center, to develop workshops, self-assessments, and other programming around digital competencies. LILAC not only advises students on career development and graduate school applications, but offers an array of civic engagement and experiential learning opportunities (internships, externships, intensives, alumnae networking, and volunteer work). Students who participate also receive professional development training that invites them to reflect on their experiences and to develop and practice skills needed to professionally communicate what they have learned.

In the future LILAC also hopes to connect similar programming to on-campus student employment. LITS team members are working with LILAC staff to integrate reflection on digital competencies into the professional development training offered to students and help students learn to talk about their competencies confidently and professionally. We are also helping LILAC with programming that encourages Bryn Mawr women to consider careers in tech-related fields, such as recent STEM and technology "intensives" or visits with alumnae in technical fields. At Bryn Mawr we think of digital fluency as an essential component of leadership and success in the 21st century, and the College is committed to ensuring systematically that our graduates are empowered with this critical capability.

Conclusion

Given recent high-profile media reporting on "fake news," Facebook algorithms, and net neutrality, critical questions about digital technology are more prevalent among higher education communities than ever before. Faculty, librarians, academic support staff, students, alumnae, and board members are thinking about personal and institutional digital identities and how those identities, and their ability to shape those identities, might be impacted by decisions that corporate, technical, and governmental actors make about the digital environments in which we all work, learn, play, and live. Digital citizenship can offer a framework for organizing campus interest, discussion, and programming around these issues, in a way that resonates deeply with institutional values and missions.

As the initiatives described here suggest, digital citizenship can also provide a valuable opportunity for IT staff to partner with faculty, students, and colleagues across departments on developing and implementing programming that is directly relevant to their institution's mission and strategic goals. Helping faculty and students think through the implications of technological choices is a key part of the professional roles of the authors, who are educational technologists, instructors, librarians, and administrators. However, digital citizenship conversations can open this kind of interaction to a wider range of IT professionals. Network and systems administrators can contribute valuable technical knowledge to critical discussions about topics like network architectures, data structures, and data security, helping faculty, students, and nontechnical staff think critically about the political, economic, ethical, social, and personal effects of "technical" decisions. "Practical" IT projects such as implementing a data security policy, choosing a learning management system, or providing information security training to faculty, students, and staff during Cyber Security Awareness Month, can become teaching moments in this broader campus conversation about digital environments, digital identity, and digital citizenship.

If we have learned nothing else from our comparison and discussion of digital competency initiatives, it is that successful initiatives will build on local interests, opportunities, and needs. There is no single way to launch an initiative: at Capital University and Keuka College, for example, developing a digital citizenship course (a first-year seminar and a SPOC, respectively) played an important role in helping stakeholders understand what digital citizenship is and why it matters, while at St. Norbert's and Bryn Mawr Colleges, digital citizenship or competencies became a way of connecting existing curricular and co-curricular offerings. Existing institutional structures can provide valuable entry points or partners for digital citizenship programming, as in the case of St. Norbert's Full Spectrum Pedagogy and Bryn Mawr's Leadership, Innovation, and the Liberal Arts Center (LILAC) programs. Institutional context also matters greatly. As a women's college, Bryn Mawr has focused more explicitly on empowering students in the digital realm than its peers. Similarly, St. Norbert's and Keuka College's digital citizenship initiatives have been shaped by broader institutional attention to "whole person development" and integrating digital learning into the curriculum, respectively.

We anticipate a continued maturation of these varied digital literacy initiatives as they prove their value to students before and after graduation. Other colleges and universities will no doubt launch and continue to develop their own digital literacy programs to support student success. We look forward to hearing more about the digital efforts at other institutions and learning from their success stories.

Further Resources

-

Global Digital Citizen Foundation Page 7–8 of this document [http://cdn2.hubspot.net/hubfs/452492/content/GDC_handbook.pdf?t=1487694478172].

-

"Digital Citizenship in the Liberal Arts Community" ELI Workshop Participants

Annie Almekinder is director of Digital Instruction, Keuka College.

Enid Arbelo Bryant is assistant professor of Communication Studies, Keuka College.

Autumm Caines is associate director of Academic Technology and adjunct instructor, Capital University.

Krissy Lukens is director of Academic Technology, St. Norbert College.

Nancy Marksbury, Assistant Professor, Digital Learning & Services Librarian

Angela Narasimhan, Assistant Professor of Political Science

Sundi Richard is an instructional designer, St. Norbert College.

Gina Siesing is CIO and director of Libraries, Bryn Mawr College.

Jennifer Spohrer is manager of Educational Technology Services, Bryn Mawr College.

© 2017 Annie Almekinder, Enid Arbelo Bryant, Autumm Caines, Krissy Lukens, Nancy Marksbury, Angela Narasimhan, Sundi Richard, Gina Siesing, and Jennifer Spohrer. The text of this article is licensed under Creative Commons BY 4.0.